Return to top

Nine Drawings

Shahd Abusalama

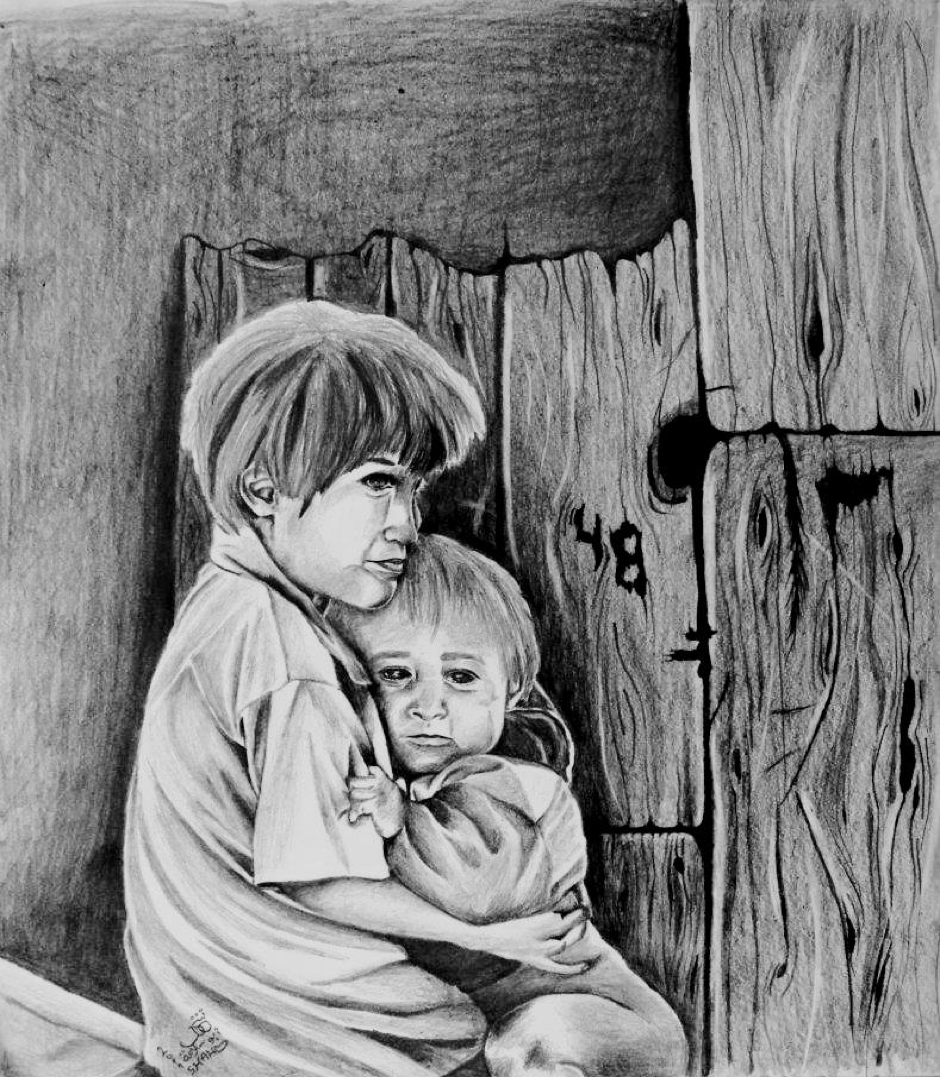

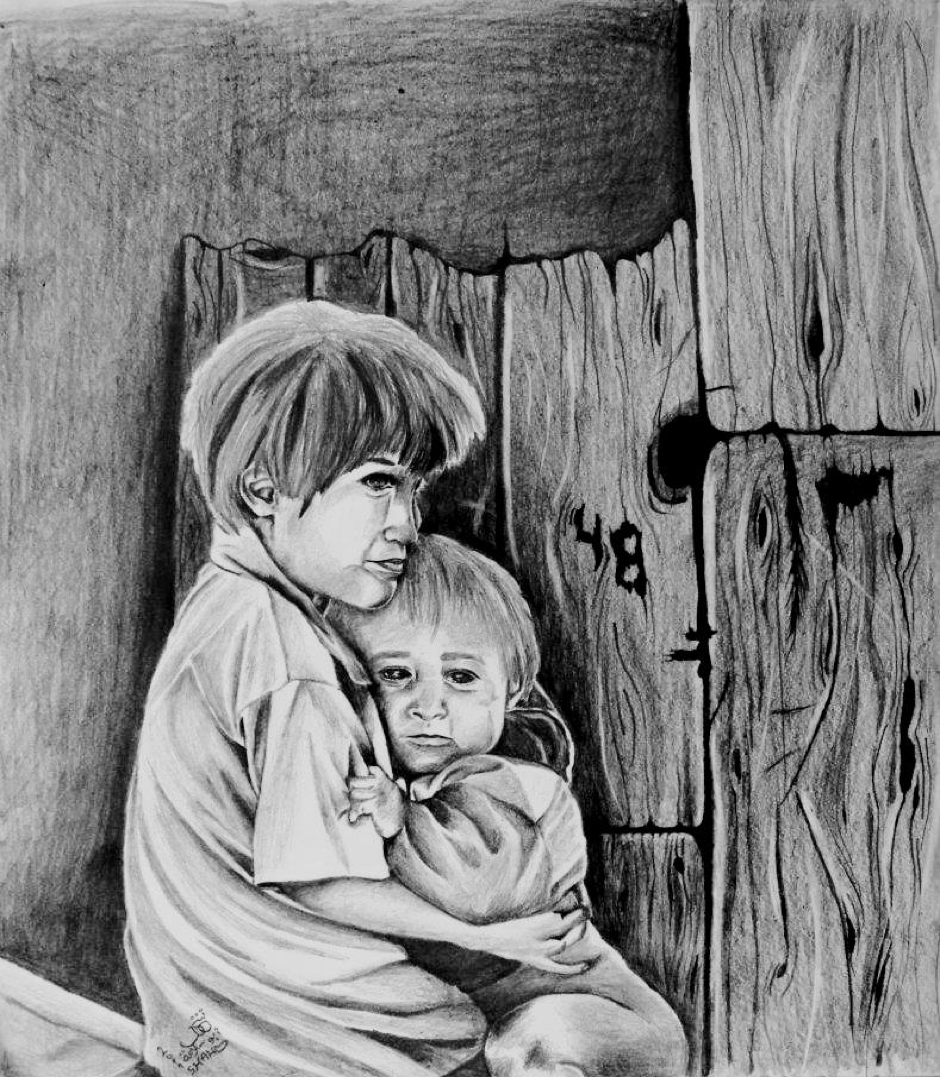

Figure 1:

An optimistic eye

____________________________________________________________

¶ The well-known Palestinian artist and art

historian Kamal Boullata, who died in August

2019, left behind a wealth of art and research, rooted in questions of

identity, resistance and exile. In his 2002 essay “Art under the Siege” he

asked:

“How

does one create art under the threat of sudden death and the unpredictability

of invasion and siege? More specifically, how do Palestinian artists articulate

their awareness of space when their homeland’s physical space is being

diminished daily by barriers and electronic walls and when their own homes

could at any moment be occupied by soldiers or even blown out of existence? In

what way can an artist engage with the homeland’s landscape when ancient orange

and olive groves are being systematically destroyed? When the grief of bereaved

families is reduced by the mass media to an abstraction transmitted at

lightning speed to a TV screen, what language can a visual artist use to

express such grief?”

These

questions have long troubled Palestinian artists as they attempt to process and challenge a precarious and dehumanising reality shaped by military occupation,

apartheid and siege. Here I make a humble effort to

frame drawings that I created in my

late teens and early twenties, situating them within a wider history of Palestinian cultural resistance.

Since the day I was born, in Jabalia Refugee Camp in the north of the

Gaza Strip, the biggest and most densely populated refugee camp in Palestine, I

have never known what life is like without occupation and siege, injustice and

horror. Like the child depicted in Figure 1,

growing up in a refugee camp was the window to understanding our reality under

Israeli colonial occupation. Art has been the way I naturally sought since a

very early age to describe what I felt was indescribable.

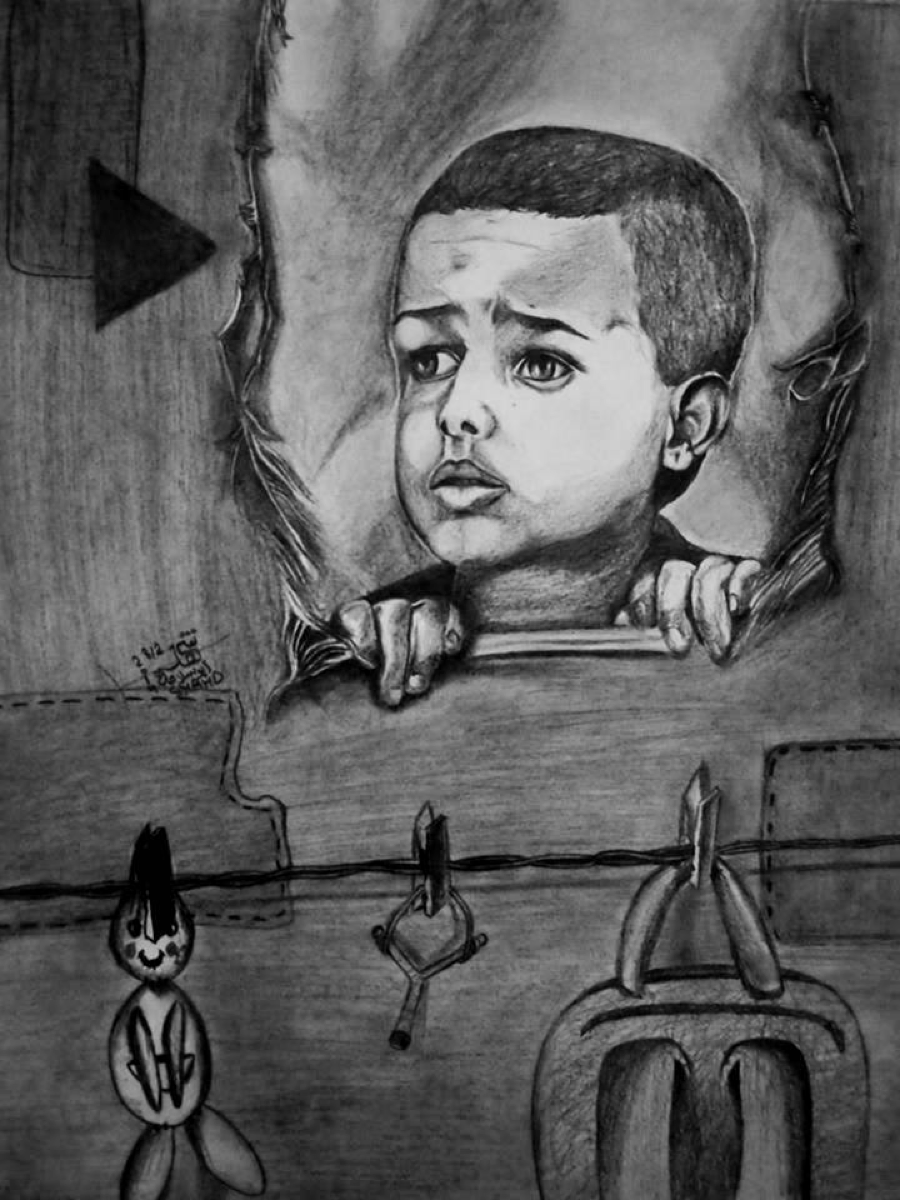

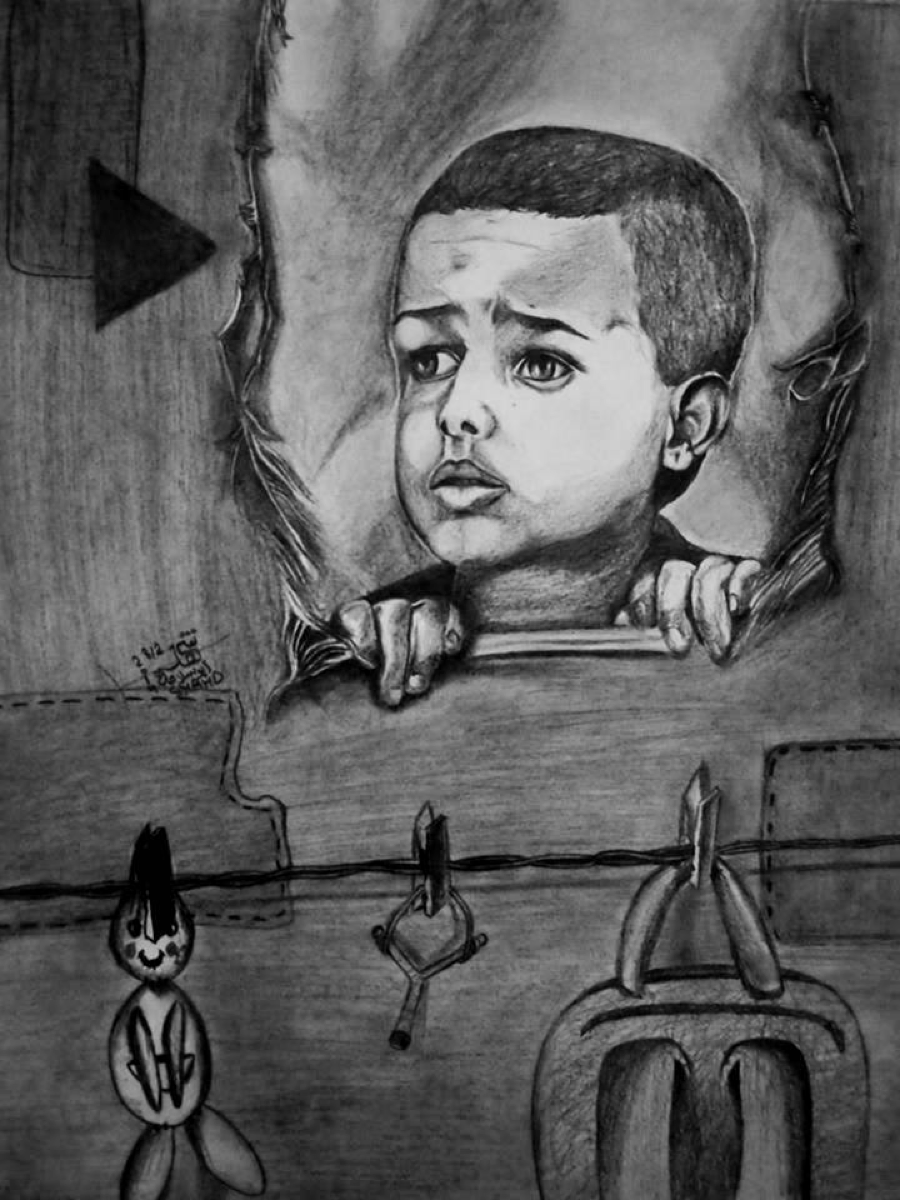

Figure 2: Displaced

____________________________________________________________

¶ I was only nine years old when my

parents noticed my drawing skills. At

that time they were limited to black warplanes, pillars of smoke in the

sky and crying eyes. This coincided with the eruption of the second intifada in

September 2000, when I used to accompany my mother and aunt to the martyrs’

funeral tents to offer our condolences. I used to hate the green colour, as it

was associated in my memory with loss and mourning; the martyrs’ funeral tents,

which were disturbingly visible in the

landscape of the Jabalia refugee camp, were mostly green. The

first poem I ever learned by heart was one by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud

Darwish entitled “And He Returned …In A Coffin”. As a

nine-year old girl, I stood in front of many mourning families in those green

tents, looked into their tearful eyes, and in a powerful but shaking voice I

recited:

It was moments

like these, during the tumult of the second intifada, that fundamentally shaped

my consciousness about the land and my place in it. Since childhood, the scenes

of war, the faces of martyrs, the injured and political prisoners, the weeping

of the martyrs’ relatives over the loss of their beloved, have been haunting me

with a desperate wish for this injustice to end. These scenes pushed me to seek

art as a way to process those extraordinary surroundings, to reconcile with my

wounds, to express my emotions, memories and experiences, much of which is

collectively shared amongst the Palestinians.

Creativity in

such a context is not only a necessary tool for survival in a taxing background

of violence but, as Boullata contended in several articles, an expression of survival. For

example, the “100 Shaheed—100

Lives” exhibition, by Ra’ed Issa

and Muhammad Hawajri from Bureij

Refugee Camp in central Gaza, commemorated the first one hundred victims of the

al-Aqsa intifada. The exhibition grew out of the artists’ intimate contact with the bereaved families and

violence. Using a blend of abstract, metaphorical and representational language, their artwork expressed “the

state of being a survivor of and eyewitness to daily death.”

____________________________________________________________

Figure 3:

Reflections

____________________________________________________________

Reflections

¶ Palestinian art, from the twentieth

century up until now, has served as a visual reflection of the

Palestinian struggle. It aimed to depict the reality of the Palestinian

people, their hopes and aspirations, their suffering, and urge for mobilisation

at an international level against injustice. It also acted as a tool to

provide a self-representational counter narrative to the hegemonic Zionist

one which demonised the Palestinian history and

people to justify their colonial domination.

Among many other

forms of cultural resistance, art for many Palestinians was seen as a way to

participate in writing their own visual narrative, to critically and creatively

engage with their socio-political surrounding matters, to express their

identity, and to amplify the Palestinians’ political demands. Against the

humanitarian imagery that reduced Palestinian refugees to victims, or colonial

representations that slammed them as terrorists, Palestinian art has sought to

transform the image of the Palestinians into active agents of revolutionary

change.

Over the course

of the Palestinian struggle, the Palestinian people increasingly regarded

artworks that expressed their living conditions under Israeli control as a

means of resistance. The Palestinian art movement thrived in the 1970s despite

many challenges, including the lack of any art infrastructure. Many Palestinian

paintings displaying the “forbidden” colours of the

Palestinian flag have been confiscated, and many artists, such as the renowned

artist of the Intifada Sliman Mansour, faced

detention due to their art that Israel perceived as “an act of incitement”. Let

us not forget the late Palestinian influential exiled artists Ghassan Kanafani and Naji Al-Ali, whose artistic and literary production led to

their murder in Lebanon and London respectively.

Personally,

observing the Palestinian children being born in a difficult reality that

subjugates them to terror and trauma at very young age was the most painful. Most of my drawings are of Palestinian

children whose innocent facial expressions I find most telling and urging for

liberation and social justice.

____________________________________________________________

Chains Shall Break

¶ Moreover, being a daughter of an

ex-detainee means I have grown a unique attachment to the plight of the

Palestinian political prisoners, not only from a political perspective but also

from a personal one. As a 19-year-old boy, my father spent a total of fifteen

years in Israeli jails, but he is only one amongst over a million Palestinians

who experienced detention since 1948, including children, women and elderly

people. The stories of resistance, resilience and repression that I grew up

hearing about his stolen youth have made me develop a particular passion to

this cause. Currently, over 5 thousand Palestinian detainees are in Israeli

captivity with no access to their most basic rights allowed by the Israeli Prison Service, including fair trial,

proper medical care and family visits.

The plight of

Palestinian political prisoners and their families, however, is not given the

deserved attention in the political arena, especially at an international

level. They are not only marginalised, but also dehumanised

in a media discourse that tends to reduce them to mere statistics or defines

their resistance in terms of “terrorism”, similar to the way Nelson Mandela and

other anti-apartheid activists in South Africa were represented. The drawings contained here were an attempt to

challenge such reductive and hostile representation, humanise

them, draw attention to their captive struggle inside Israeli jails and call

for action.

Throughout my

upbringing, I have witnessed their families’ immense pain as my family joined

their weekly protests in front of the Red Cross in Gaza, calling for

dismantling the Israeli prison system and freedom. As I developed more skills

of expression, I coupled drawings with writings that recorded stories of

Palestinian detainees and their families with whom I developed an intimate relation

after years of weekly protests. Many expressed their pain as a form of

imprisonment in time, another theme that inspired my drawings in my attempt to

communicate the families’ longing for a reunion with their beloved ones without

barriers in between. The

ticking of clocks, the tears, the longing.

I tried to depict

their determination to break their chains, which they

expressed repeatedly in legendary hunger strikes. “Hunger strike until either

martyrdom or freedom” is a motto that many prisoners adopted across the history

of the Palestinian Prisoners Movement. The drawing in Figure 4 aimed to

illustrate the defiant spirit of this motto.

Figure 4: Hunger until freedom – For Samer Issawi and all

freedom fighters in Israeli jails

____________________________________________________________

Figure 5: Traumatised childhood

____________________________________________________________

Figure 6: Fear of the

unknown

____________________________________________________________

An ongoing Nakba

¶ My generation, the third-generation

refugees, was already blueprinted with the traumatic events of the Nakba, which for Palestinians is not

only a tragic historical event, only to be commemorated once a year with events

such as art exhibits and national commemorations. “It was never one Nakba,” my grandmother Tamam used to say asserting that ethnic cleansing was never

a one-off event that happened in 1948, when Palestinians became stateless

refugees. The Nakba is experienced as

ongoing; an uninterrupted process of Israeli settler-colonialism and domination

that was given continuity by the 1967 occupation, the violent invasion of

Beirut and the Palestinian

refugee camps in Lebanon, the two intifadas of 1987 and 2000, and the siege of Gaza and the constant bombardments

and demolitions across the shrinking occupied Palestinian territories.

Growing up

hearing our grandmothers recount the life that they had before, the dispossessed lands that most would never

see again, has formed the collective memory of the Palestinian people. My

grandmother described a peaceful life in green fields of citrus groves and

olive trees in our original village, Beit-Jirja, one

of 531 villages that were violently emptied of their inhabitants and razed to the ground in 1948. The landscapes,

the tastes of their fresh harvests, the sounds of peasants’ dances, the joy of

family gatherings and traditional weddings, all burdened her traumatic memory

in a sudden rupture that turned our existence into non-existence. She found

consolation in storytelling that cultivated inside her children and

grandchildren a burning longing for return and a life of dignity.

The continuity of

our liberation struggle, from one generation to another, resembles hope for the

Nakba generation and their descendants, another theme that several of my

drawings attempted to express – see Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9. They were my

response to several Zionist leaders who assumed that “the old will die and the

young will forget.” The drawings come to assert that the old may die but the

young will keep on holding the key, until our inalienable right to return is

implemented. In 1948, most refugees fled in a haste and fear, taking whatever

they could carry at a moment’s notice. They carried the keys of their homes in

their exodus, and although many know that their homes no longer exist, they

held onto their keys, passed them

to their children, making the key become a symbol of the undying Palestinian

hope that return is inevitable. The young generation is perceived as those who

will carry the burden of the cause and continue the struggle of the previous

generations until freedom, justice, equality and return to the Palestinian

people. Thus, Palestinian children became the symbol through which “We nurse

hope”, as Mahmoud Darwish said.

____________________________________________________________

Figure 7: The young will carry on the struggle

____________________________________________________________

Figure 8: Breaking the State of Permanent Temporariness

____________________________________________________________

Memories of War

¶ The majority of

Palestinians have become politicised as

a result of the complex and intense political reality that shapes

every aspect of their lives. I am no exception. Art for me was an expressive

tool in which I found empowerment for

my voice. It served as a tactic to overcome the state of siege and

occupation imposed on us, to escape the feeling of helplessness that can be

easily felt in such suppressive and oppressive life conditions that the

Palestinian people endure. It was also a tool that I used to engage politically

and socially with the harsh surrounding. With internet becoming accessible, I

resorted to online social networks to reach out to the international community,

believing that the Palestinian people’s struggle for liberation is a central

global issue.

The turning point

of my life was at the age of seventeen, after witnessing the 22-day massacre

that the Israeli occupation forces committed against our people in Gaza in

2008-9. During that dismal period when we remained in darkness amidst the

continuous bombing, destruction and mass killing of Palestinians in Gaza, I had

a terrible sense of alienation from the rest of the world communities who were

busy marking New Year Celebrations with fireworks.

It all erupted

while we were attending the mid-term exams. It was a normal day until Israeli

warplanes started shelling all over the Gaza Strip, announcing hundreds of

victims from the first hour. The chaos that ensued at school and the living

horrors that followed for 22 days of being

struck by military machines from land, sea and air, left a

lasting impact on everyone.

One of the most

memorable moments is when one night, I was sitting in blackout, surrounded by

my mother and siblings in one small room of our house under one blanket. No

voice could be heard, just heartbeats and heavy, shaky breaths. The beating and

breathing grew louder after every new explosion we felt crashing around,

shaking our home and lighting up the sky. Then suddenly, the door of our house

opened violently and somebody shouted, “Leave home now!” It was my dad rushing

in to evacuate our house because of a bomb threat to a neighbour. I remember

that my siblings and I grasped Mum and started running outside unconsciously,

barefoot. For three days we stayed in a nearby house, powerless as we sat,

waiting to be either killed, or wounded, or forced to watch our home destroyed.

This merciless

and inhumane attack killed at least 1,417 men, women and children. I wasn’t

among them but what if I had been? Would I be buried like any one of them in a

grave, nothing left of me but a blurry picture stuck on the wall and the memory

of another teenage girl slain too young? Would I have been for the world just a

number, a dead person? I refused to dwell on that thought. Many drawings of

mine, such as those presented here,

were inspired from memories attached to this traumatic event and similar

experiences that proceeded. The trauma was relived whenever an attack was

repeated. Most importantly, resorting to art was a necessary means that

helped me preserve my sanity and overcome the harsh traumatic events that I experienced throughout my

life in the suffocating blockade of the Gaza Strip.

____________________________________________________________

Figure 9: We Shall Return

____________________________________________________________

References:

Kamal Boullata,

“Art under the Siege”, Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 33, no. 4

(Summer 2004), pp. 70-84

Mahmoud

Darwish, And He Returned in a Coffin, from the author’s first

collection Olive Leaves [,

published in 1964; reprinted 2014.

·

All drawings were done with 2B and 4B lead pencil on

paper, 14 cm x17 cm