Four Sketches

Texts: Harriet Paintin

Illustrations: Hannah Kirmes-Daly

______________________________________________________

1. Kobane

in Exile

He stood out from the dusty mass of people arriving and being put

onto buses; holding himself with pride, the face of a fighter. We watched him

from a distance as he paced up and down, like a lion in a cage, assessing this

impossible environment where refugees are processed, ticketed and given drab

sandwiches. He approached us, and picked up our darbouka drum. His slender fingers tapped out a rhythm as he sang, his voice heavy and melancholic. He stopped abruptly,

and complained that his fingers were too cold.

“You have the face of a guerrilla.” he pointed his long finger in Hannah’s face. “A guerrilla fighter.”.

Taken aback, we asked him where he came from. His eyes, hardened yet fiery, bore into us as

he hesitated before responding.

“Kobane.” He gave the two finger victory salute, and we nodded in

understanding. He stepped back into the crowd, pulling his red sports jacket

around him and glaring across the road, before turning on his heels and coming

back towards us, demanding what we know of Kobane, Rojava. We shared fragments of information about Kobane, a general awareness, and the tension in his body

relaxed somewhat, as if reassured by the fact that awareness of the long fight

which was his whole life had reached the shores of Europe before him.

He pointed again at Hannah’s dark hair, and eyebrows. “Kurdish women are the symbol of our

struggle. There is nobody stronger, not even men! In Iraq they have been

fighting Isis for more than a year, but our Kurdish women defeated them in a

month. For five years I was fighting, with them…” His voice took on a tone of sadness, reflected momentarily in

his strong face.

Hannah asked if she could draw him, and he was surprised. “It is my honour,’ he replied, and stood completely still as Hannah’s pen flew across the

paper, outlining his strong features, hollowed

and toughened from years of fighting and a long, perilous journey.

When the portrait was finished, a fleeting smile flashed across

his face and he wrote his name in the beautiful, flowing Kurdish script. Agrin, meaning

fire. He insisted that we tag him on Instagram,

writing his profile name in my notebook. He pointed at the name, and said, “She was a guerrilla, who fell during

the fighting …”

Figure 1: From Kobane

______________________________________________________

2. Memories from the village

Moria at night, the smoke hanging thick between

the olives trees, trees 100s of years old which have been all but stripped bare

as the branches are used as firewood. In

Being a refugee is an experience that

people are currently facing – it is not an identity. In these conditions, where

most conversations revolve around the horrendous journeys undertaken so far,

and apprehension for what lies ahead, it can be difficult to let the individual

shine through. But human interactions that take place around a fire at night,

faces illuminated only by the flickering firelight, jokes, laughter, missing

home, show us that we all carry

with us our personal stories of home, teenage crushes, embarrassments and in

these moments it becomes clear that by no means is the refugee experience all

that defines these people.

Sitting around a fire one particular

evening with a group of Pakistani men, Hannah painting in the near darkness,

their questions for information about the journey ahead quickly fell away into

laughter and shared moments of embarrassment.

“During my childhood I lived in a village.

Yeah, I used to play in the village, guli danda, football. no, not cricket – but guli danda is just like cricket. We used to have fun, me

and my friends.”

He sat in the middle of the group with his

headscarf bound around his head in exactly the same way you see in towns and

villages across South Asia. His eyes crinkled with laughter as he opened the

doors to his memories, the cheeky things he used to get up to in his youth.

Four others sat and watched with laughter in their eyes, feeding cardboard and

twigs into the fire.

“I had a girlfriend,” he went on, “and

I used to go to her house when she telephoned me. In our villages this sort of

thing isn’t allowed. Once when I was there her mum came home, and I had to hide

in another room. Her mum came in and looked around, then

she sat down. I had to walk past her to get out the house! So, I dressed in

women’s clothes, I put on the niqab, and went outside. When I

passed her mum I said ‘salaam alaikum’, she

replied ‘walaikum asalaam’,

and I walked on. Then another day, this happened again, and I did the same

thing.”

Laughter filled the atmosphere between us

and he grinned sheepishly before continuing.

“Sometimes I used to dress up in the niqab and go to the shop in the village, and ask for

Pepsi, sugar, other things. Then I’d say I didn’t have any money, I would write

my name and come back later,”

and he agreed, I wouldn’t go back later! Sometimes I’d walk around the village

wearing the niqab, go up to women and

say ‘hello hello’.”

At this point, one of the others spoke up: “Sat here talking with you people

like this, it’s refreshed us.

We’re not thinking about those we’ve left behind, the difficult journey, this

torment has left us for the moment. We’ll look back on this time fondly, inshallah, we’ll remember this.”

Figure 2: Memories from the village

______________________________________________________

3. Untold Stories of the Roma: Margarita

Podu Turcului weekly

market – a cacophony of horse carts, pigs being sold from the boot of a car and

homemade alcohol. Different Roma communities from across

Margarita was sitting on a small stool

surrounded by second hand shoes spread out on a plastic sheet; she stood out

amongst the other stallholders in her bright pleated skirt and colourful

headscarf. Her deeply lined face crinkled into a smile as she enthusiastically

gestured for us to sit down.

“Jesus didn’t make a distinction between

gypsies and non-gypsies, so why do people? We’re honest people, we want to work

and take care of our family. That’s it.” Her voice was

strong and impassioned, her gestures were so emotive. “There’s a lot of

discrimination when people don’t understand the gypsy culture. Where I come

from, in

She gestured towards her wares spread out

before her, shoes of all colours and sizes. “We have all of these things to sell and

we try to come to places like this where people don’t have much money, to try

and help them in this way. The people are very happy to buy good things, these

shoes come from

The Roma community are

often portrayed as needy or disadvantaged. Margarita strongly tried to assert

that she is neither of those things; rather, her resilient voice stressed the

help that she tries to bring to people within her own community. She waved as

we stood up to leave and, as we parted ways, she wished us “health, love and

power”.

28 September 2016

Figure 3: Margarita

______________________________________________________

4. Tracing the lines of hope and

remembrance: the Syrian camp, Calais

Following the

night in the Sudanese camp, we hoped to visit the Syrian camp which is made up

of fifteen men from a same village in

Figure 4: At the Syrian camp – Shaving

Hannah began

communicating in her broken Arabic and passing round pieces of paper,

encouraging the others to participate in the drawing while Ed and I took out

our violins and played a couple of tunes. People began dancing, shouting and

joking; the charged atmosphere swept us all up and carried us through. They

played Syrian music on their phones and we got up to dance with them. Hand in

hand we moved round and round in a circle, stumbling over the steps as they

leapt and stamped and shouted.

Figure 5: At the Syrian camp – Music

By sharing music,

art, and dance we were now feeling at ease, familiar. Hannah sat with a small

group, sketchbook on her lap, and impromptuly said, “tell me

about your hometown, your village, what does it look like? I can draw it for

you.”

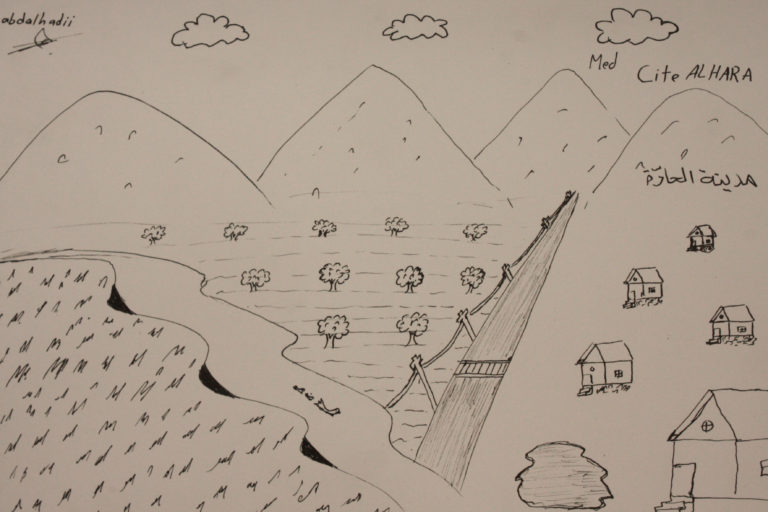

They leaned in:

“There are the mountains, the river… the olive trees… and houses,

my house is here… yes, the mosque.”

They began

pointing out where their houses would be, showed us photos. They wrote their

names in Arabic above their houses. Gradually the village took shape on the paper

in front of us, and the story took a turn.

“Then there are the planes, flying over… and the police, with their

guns… the graveyard…”

“Here a dead

child, near my house. They died, the whole family… they were eating, in

Ramadan… all the family died. Seven people. My house…

BOOM! No house now. In the past, here was the house… Now, no house… bombs

broken.”

One man started

playing music on his phone, and sang. To us, to the image, but also to their

hometown, “the olive trees, the

olive trees…”

His eyes filled

up with tears, “I want to go

home, I want to return.”

Figure 6: Drawing the village [1]

But for many of

these men there is no home to return to. I sat talking to one man, who told me

that the difficulties and danger of life in

“Here there are problems. At home there are problems. In

We parted,

trying to not to show how shaken we were by what we had just experienced,

handshakes and “good luck!” and “see you in

As Hannah

finished tracing in the streets and school of their village, one man

tentatively reached for her sketch pad and pen and sat hunched over, drawing

out his own memory of his village. [Below]

Figure 7: Drawing the village [2]

The next morning

we passed by the Syrian camp again to give them some photocopies we had made of

the drawing. After yesterday’s highs and lows the atmosphere was slightly

subdued; frustration, a sense of desperation and the desire to leave hung in

the air. The man who had been shaving when we arrived the day before grabbed

Hannah’s sketchbook and started rifling through it. He stopped on a sketch and

pointed at one of the men.

“This morning, he went under a lorry and made it to

_______________

See also the

video version of this story:

Mapping the lines

of flight and hope :: https://youtu.be/DUAkP5nz4_c