The avian guilds of North America, along with those of Eurasia, were once the exclusive domain of Enantiornithes, the opposite birds, with their clawed wings and upside-down ankles. However, the subsequent millienia have seen true birds, Euornithes, rise into supremecy. They way has not been easy.SAMPLE TAXA:CORACIIFORMES

Clade Coraciiformes is an ancient and diverse group of primitive perching birds whos roots date back to the Eocene. Ranging from tiny, wren-like todies to the giant, South American regios, the coraciiforms run a wide gamut of avian forms.The clade Coraciiformes began as a group of generalist ground birds very much like the modern Brachypteraciidae (the widespread ground-roller assemblage), and quickly diversified into a number of forms. During the Eocene and Oligocene, the coraciiformes were arguably the most specious of the bird lineages, and certainly enjoyed a wide range, with representatives on of the Laurasian continents. The Messel oil shales hold a number of coraciiformes, many of them virtually identical to modern rollers, ground-rollers, and sylphs. With the rise of clade Twitaviformes, however, the coraciiform march of progress began to falter, the clade becoming completely extinct in the Old World, but for a few strongholds in Africa and Madagascar. For much of the remainder of the Tertiary, coraciiformes barely hung on in the Old World with many clades (hornbills, hoopoes, scimitar-bills, and cuckoo rollers, to name a few) going completely extinct. In the New World, however, the story was different.

The twitavian penetration of North America never advanced very far, and the continent's native assembly of coraciiforms continued to rule with little opposition. During the Miocene, the American coraciiformes experienced a renaissance of diversity, radiating into many bizarre niches, most notably the piscivorous alcedinids (kingfishers) and the bizarre, wood-boring dirostrids (pickpeckers). During the Pliocene and Pleistocene, these clades spread from North America to colonize every continent but Antarctica (there are even alcedinids in twitaviform-dominated Australia).

Meanwhile, in Africa, the Pliocene saw a new adaptive radiation of Coracii, the primitive branch of Coraciiformes supposedly relegated to obscurity by the twitaviforms. Sub-clade Coracii, the most basal branch of the coraciiform tree, suddenly exploded across Africa and Eurasia as Parabrachypteraciidae. Today, the generalist/scavenger parabrachypteraciids are ubiquitous in Africa, Eurasia, and the Americas, filling the niches that, on Home-Earth, would be occupied by the passerine corvids, the crows.

While the Americas remain center of coraciiform diversity, many of the clade's 500 known species may be found on every continent except for Antarctica.

Dirostridae

Dirostrids, the pickpeckers, are the strangest of the coraciiformes, and arguably the most sucssesful. These creatures are reletively new additions to their family tree, arising some time during the Pliocene and quickly spreading from North America to Eurasia, Africa, and (somewhat later) South America.

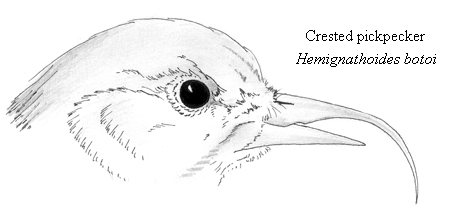

The pickpeckers possess a beak structure unique in Spec's birds, although they bear a superficial resemblance to the passerine akiapolaau (Hemignathus wilsoni) of Home-Earth's Hawaii. A pickpecker's upper mandible is highly curved and hook-like, while the lower bill forms a blunt, robust pick, similar to the beak of an RL woodpecker. Pickpeckers feed by bracing themselves against a vertical tree-trunk will powerful talons (see below) and a stiff, bristly tail. They then slowly walk about the bark, feeling with their feet for the tell-tale vibrations of a wood-boring insect larva. Upon locating food, the pickpecker opens its mouth, specialized mandibular joints allowing the bird to yawn impossibly wide, and then drives its lower bill into the wood, shattering bark to expose the hiding food. Pickpecker skulls are composed of rather spongy bone, and their necks articulate in such a way that their hammering motion is only possible on a single plane, thus avoiding the shearing forces that would pulverize the birds' brains. A pickpecker may hammer at wood at speeds of 15 to 20 kph, stripping the protective bark from above a burrowing grub that the bird may then extract with the aid of its curved, picklike upper bill.

(Picture by Daniel Bensen)

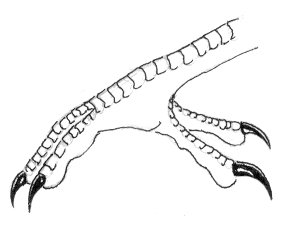

Fig 2: Zygosyndactyl footAnother interesting feature of the dirostrids physiology are their feet. Pickpecker toes are arranged in a unique 'zygosyndactyl' configuration with digits one and four fully reversed and opposed to digits two and three, which are fused at the first joint. Zygosyndacylity is no doubt a product of the kingfishers' zygosyndactyl feet evolving in convergence with the syndactyl feet of the woodpeckers of Home Earth. The zygosyndactyl arrangement gives a pickpecker a firm hold on its vertical perch, and gives the bird the leverage necessary to hammer through wood.

Pickpeckers most likely evolved from insectivorous coraciiforms similar to todies or motmots (although dirostrids are considered basal alcedinoids rather than momotoids, they may be closer to motmots than kingfishers). Many motmotoids probe trees for wood-boring insects, picking away bark with their tiny beaks, and the dirostrid feeding apparatus probably evolved as an extension of this behavior.

SAMPLE TAXA:

AGILIFUGIIFORMES

The agilifugiform birds, the swoops, are a branch of clade apodimorphae (swoops and hummingbirds) and are widespread in the North America (with some species found in Northeastern Eurasia). These birds originated in South America, and, along with the twitavian mistriders, have become the dominant high-speed insectivores of the New World.Agilifugiidae

The most specious subclade of Agilifugiiformes, agilifugiidae includes most of the the high-speed chasers of insects common to the New World.