SLOVENIAN HISTORY

Concise History of Early Slovenians

to be read in conjunction

with the brochure

Razstava na Ptuju by Rev. Ivan Tomažič

Most people educated in Slovenia over the last century have been told that Slovenians settled in Central Europe in the Sixth Century coming from behind the Carpathian Mountains. New evidence shows that, in fact, Slovenians are descendants of the indigenous people of Central Europe.

For those who wish to familiarize themselves with the basics of Slovenian history, the book VENETI: First Builders of European Community, written by Venetologist, Prof. Dr. Jožko Šavli, poet Matej Bor and Prof. Rev. Ivan Tomažič, is absolutely essential reading. Combining many decades of research, VENETI offers a careful study of facts essential to the understanding of the Slovenian past.

The 6th Century settlement theory implies that Slovenians moved within one generation from mud huts to the founding of their state of Carantania, and totally eradicated the language of the area's "original population". This theory is simply not logical or credible. The extract below is a concise account that there is much more to Slovenian history than was previously believed, followed be illustrated evidence.

Carantha http://www.niagara.com/~jezovnik is a treasure for history buffs where you can also order the book Veneti: First Builders of European Community.

For a Summary of the Early Slovenian Hstory click here.

The Cover Page

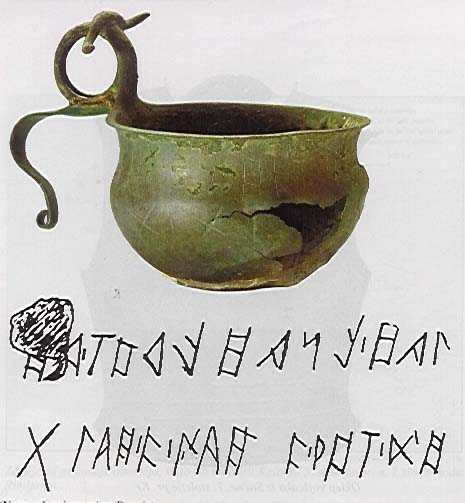

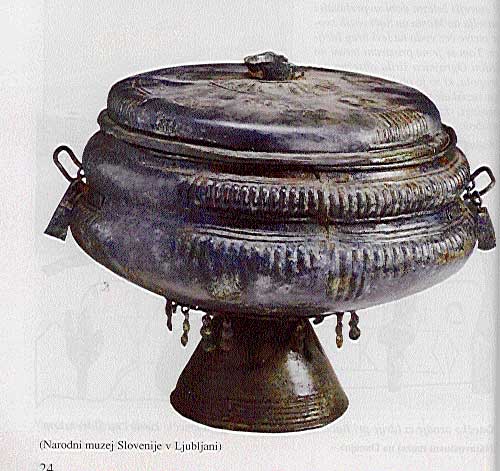

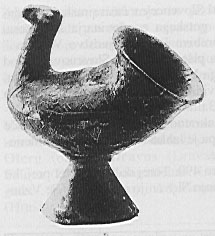

The Urn from Neviodunum

- Drnovo near Krško.

(National Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana)

Funeral Urns in the form of a house were a specialty of Veneti at Dolenjska. They imitate buildings with a rooster on them that signifies the start of a new day and the rooster on the urn signifies new life after death.

The Exhibition

VENETI IN SLOVENIA

Ptuj 2001

***

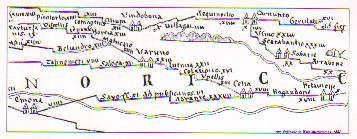

Inside Cover

The Map of Roman roads in the area of Karavanke from the 4th Century A .C. by Peutinger that shows ZALOKA written in Latin script ‘Saloca’ and it indicates Slovenian presence.

The Exhibition 'Veneti in Slovenia' was prepared by the Slovenian World Congress in cooperation with the Library of Ivan Potrč at Ptuj with the help of Reverend Father Ivan Tomažič, CIP, NUK Ljubljana (National Univesity Library of Ljubljana), Printing, Delo, Ljubljana.

Published and Edited by Ivan Tomažič

(A-1080 Vienna, Bennogasse 21)

EXHIBITION

Veneti na Slovenskem (2001; Ptuj)

Razstava Veneti na Slovenskem, Ptuj, 2001 / Edited by Ivan Tomažič - Vienna

ISBN 961-90840-4-7

1 - Veneti na Slovenskem 2. Tomažič, Ivan

114141184

Photos from the books 'Zakladi tisočletij',

'Zgodovina Slovenije od neandertalcev do Slovanov', Ljubljana, 1998.

All rights rezerved

***

Page 1

FIRST CENTURIES

The beginnings are in the Culture of Lužice

Science was not yet able to determine what language Europeans used before the Bronze Age and how Indo-European languages evolved. From the similarity between the Slovenian and Basque language, it could have only originated before the Indo-European Age, therefore we can assume, that the Indo-European language contained Slovenian Elements. With this assumption we can understand the beginnings of the Slovenian language in the form of the Indo-European languages within the then most important culture of Central Europe, namely in the culture of Lužice. Its language is known from the bearers of Urn Culture that has its origin in the Culture of Lužice. The people are called Veneti that is the same as Slo-Veneti. For this reason we can call their language Venetic, namely, Slovenetic or Slovenski that was spread by Veneti through culture where ever there are traces of the Slav language. And it is found everywhere in Europe especially in Central Europe. It is obvious that Veneti were especially prominent on today’s Slovenian territories, where they arrived on the well-known Amber Way (Jantarska pot). Here they developed a specific center. For this reason we can claim that Veneti are the ancestors of the Slovenian nation.

The Area of Culture at Lužice according to archeological findings.

***

Page 2

The Slovenian region before the settlement of Veneti

In the middle of the Bronze age, around 1200 B.C., when Veneti began to arrive in the present day Slovenia along the Amber Way from the territories occupied by Lužice Culture, the lands were sparsely populated, according to the archeological finds, as seen from the map bellow

Settlement of Slovenia

in the Bronze Age

(From the book 'Zakladi tisočletij')

Slovenian territory was more or less always settled since the Paleolithic period. Many burial places testify to that especially Škocjanska jama, Potočka zijalka and Divje babe the location of the famous Neanderthal whistle find.

***

Page 3

Settlements some centuries after the arrival of Veneti

A considerable increase of the population on the Slovenian territory for some time after the arrival of Veneti testifies to their influx and permanent settlement. From the influence of the Culture of Urn Burials it is evident that Veneti did not want to dominate the other nations but wanted to spread their spiritual and material culture that brought people greater benefits.

yellow - settlements

green - burial grounds

From the map of the settlements

and burial grounds it is possible to see that the territory of today’s

Slovenia in the Antic and New Iron Age was tightly settled

(From the book 'Zakladi tisočletij'

***

Page 4

The Method of Burial

Prior to the arrival of Veneti and for some time after, the dead were buried in heaped graves. The Veneti introduced cremation and this practice increased to becoming significant in religious practice. With the fire the deceased was not only relieved of all material burdens but also of all evil to make life after death possible. From the Venetic inscriptions we know that prayers accompanied cremation. The practice of Urn burial gives the name to the first culture of Veneti.

On the hill of Rabotnica

to the south of Branik a large rock grave is located from the middle of the

Bronze Age in which a wood-box with the remains of a deceased was found.

In regard to the structure and the size of such graves, in Middle-Europe, they

differ from others of that era and are very spars. Because they were placed

on top of the Karst hills some archeologist assume that only selected members

of the community were buried in them.

(From the book ‘Zakladi tisočletij')

***

Page 5

The Beginning of the Slovenian Nation

From the Late Bronze Age a large number of burial sites on Slovenian territory, from Ruše near Maribor to Ljubljana and further to the Valley of Isonzo (Soča) testify of a predominantly new culture that began with the coming of Veneti. The Urnfield Culture was adopted by the original habitants of these territories and melded with Veneti into one ethnic community that formed the beginning of the Slovenian nation.

This was occurring between the 12th and the 10th Century B. C.

Urns from burial grounds

on Mestne njive in Novo mesto from the 9th Century B.C.

(Dolenjski Museum in Novo Mesto)

Page 6

Venetic and the Slovenian language

The similarity of Slovenian and the Sanskrit language is significant in establishing the connection with Venetic Urnfield Culture. The similarity is demonstrated in the book VEDA that remains unchanged since the arrival of Veneti by way of the Adriatic Sea and also in India around 1000 B.C. The title of the three books VEDA (the oldest of them being RIG-VEDA) is a modern Slovenian word. Likewise there are many other words that are the same in Sanskrit and Slovenian. There is also strong similarity in grammatical structure. Just to mention one example, the dual that is used in Slovenian, Sanskrit and also in the language of Lužice. (See the book ‘Slovenci - Kdo smo’ Page 26-29).

An example

from the book Rig-Veda.

As it is written now

in the Script of Nagari. Copying of the book over several thousand years

has resulted in the loss of the original script.

Translation: I praise

the brilliant God, the highest leader, the constant helper of the universe,

the teacher of all the noble deeds, the only purpose of devotion at all times

and the most indulgent one and the greatest giver of grandeur…

Page 7

The Venetic Script

The main proof that the Slovenian language developed from the language of Veneti are the 'Venetic Inscriptions' from 2500 years ago. They can still be understood, to some degree, only by using the bases of the Slovenian language. The Venetic Inscriptions were found not only in the region of Venice but also in Slovenia, from Idria near Bače and from Negova to Brumlje in Charintia.

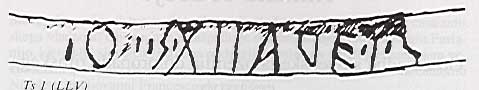

One of the helmets from

Ženjak near Negova with Venetic inscriptions.

Part of the helmet with the inscription

(Historical Art Museum in Vienna)

***

Page 8

The Proliferation of the Venetic Inscriptions

The Inscription on the helmet of Negova testify that the Venetic Culture with its language included the whole of Slovenian territory from Furlania to Panonia. This can be confirmed by the existence of the statue of the Soldier from Idria near Bače and its inscription being the same as on the helmet from Črnjak near Negova. The same type of helmet with similar inscriptions and in the same language was found in both places. A similar helmet was also found in Škocjanska jama (grotto).

|

One of the helmets from Negova from the 5th Century

B. C. Before it was laid into the grave with the deceased. It

was probably marked with a battle-axe. (Dolenjski Museum in Novo mesto) |

|

***

Page 9

Slovenia - The Center of Slovenians

Slovenian territory is a geographically significant cross road in Central Europe. Archeological evidence from gravesites suggests that Veneti developed into successful traders, including trade with the Baltic countries. Amber was a major traded item from which they produced valuable jewelry.

Jewelry made from Baltic amber ) Dolenjski Museum in Novo mesto)

Jantarska pot (Amber Way) had its ending on the Slovenian territory

***

Page 10

Expanse of the Venetic Culture and Language

The significance of the Venetic center on Slovenian territory is confirmed with additional settlement on the adjoining regions especially in northern Italy and the Eastern Alps, where urnfields are found from a later period. The pass from Krajnske Alpe (Carniolan Alps) to Koroška (Carinthia) is marked by interesting inscriptions on a stone slab at Brumlje (Wurmlach) in Carinthia.

Translation: God (might

have) gone to heaven here

One of the many inscriptions

on the rock from Brumlje that is held in the Provincial Museum of Celovec (Klagenfurt).

A silver coin dating

from the 3rd Century B.C. found at Most na Soči testifies of a connection between

Veneti in Noric and in Soča Valley.

Page 11

Venetic art on Situlas

The uniqueness of Venetic Culture in Slovenia and Italy are the famous Situlas, art from the 6th to 4th Century B.C.

Situla is a small bucket with a handle, often decorated with scenes from everyday life or from nature. The decoration is produced by a beating technique and cutting into metal. Among many situlas, only the one from Škocjan caves has an inscription.

Two situlas from Novo

mesto (Dolenjski Museum in Novo mesto)

***

Page 12

Situla from Vače

On the slope of a hill

above Vače that is partly covered by forests, right up to the top, at Sv. Križ

are many archeological sites from the times of our ancestors. This is

where the famous Situla from Vače, that dates to the 5th Century

B.C., was found.

(The National Museum of Slovenia, Ljubljana)

***

Page 13

A drawing of scenes in three

bands on a village situla

One of the scenes on a village situla

(The National Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana)

***

Page 14

THE IRON AGE

From the Venetic Urnfield Culture new cultures developed around the 8th Century B.C. On present day Slovenian territory the Hallstatt Culture and Este Culture are significant. Highly skilled work on the two-crested helmet from Vače and other similar art is attributed to the Hallstatt Culture even though it belongs to the continuation of the Venetic Culture with a specific phase of characteristics from the Iron Age that started in the 8th Century B.C. The continuation of urnfields testifies to the fact that there was no specific change or divide at that particular time.

The helmet from Vače dating to the 5th Century

B.C. (The Museum of Natural Science in Vienna)

***

Page 15

The proliferation of the Hallstatt Culture, embracing the territory north of Eastern Alps to east Slovenia, is expressed mainly in ironwork. It received its name from the city of Hallstatt because of the numerous urn cemeteries there. The skill of the Veneti with handmade craft is seen in the three vessels from the 6th Century B.C. used for decorative and cultural purposes.

(Dolenjski Museum in

Novo mesto)

***

Page 16

At the time of Hallstatt Culture in some locations, especially at Dolenjska we find many burials of skeletons, possibly because of the influence from the northwestern part of Hallstatt Culture where the Celts appeared. In any case, from this we cannot assume a change in the population, because Urn and skeleton burials appear at the same locations, either in level or in heaped graves.

Grave of a woman with rich jewelry from the

6th Century B. C. Near Stična

***

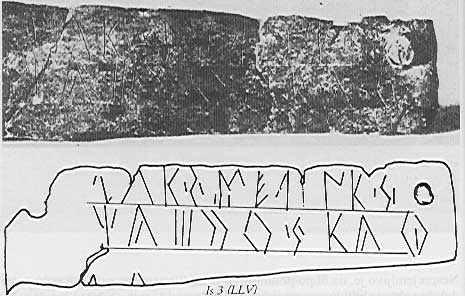

Page 17

The existence of the same population on present day Slovenian territory, including at the time of the Hallstatt Culture, is proven by the uninterrupted custom of Urn burials and with the use of the same language that is evident in the Venetic inscriptions, e.g. in the inscriptions on two vessels from a grave in Idria near Bače where the script on both is read from the left and from the right, and on the second from the right. For this reason it not possible to ignore the Slovenian meaning of the inscription. (See the book 'Slovenci - kdo smo', 188 -190).

(The Museum of Natural

Science in Vienna)

Page 18

During the period of Hallstat Culture, we frequently find soldier's equipment in graves that indicated the presence of greater danger and even possible conflicts. It is known that in the middle of the 6th Century B. C selected incursions of Skits to the Panonian plains occurred. However Skits did not settle in these parts. There is also no knowledge of other ethnic movements or conquest in the area of present day Slovenian territories.

Armor of a soldier from

Stična dating from the 7th Century B. C.

(The National Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana)

***

Page 19

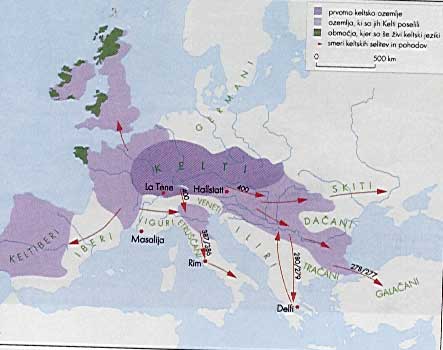

The Hallstatt Culture was partly replaced by the Tene Culture introduced by the Celt. This was the first invasion of both Venetic territory and ethnicity. However the Celts came to the Slovenian region relatively late, namely around 250 years B. C., during their return from Greece after being defeated by the Romans. When the Romans arrived in present day Slovenia, in the 1st Century B. C., there is no mention of the Celts. There are also very few remains of Celtic material culture. From all this it is obvious that they could not change the character of the region. This was not even their intention. Therefore it is totally unsubstantiated to hint of some kind of 'Celtisized aborigines' on Slovenian territory.

Dark violet = first Celt territories,

light violet = areas of Celt settlement, green = present now

The map shows the areas that were settled by Celts, from 5th Century

B. C. to the arrival of Romans

***

Page 20

Proof of uninterrupted Venetic population and their customs, also during the time of the Celtic presence, are the graves on Kapiteljska njiva (Fields) in Novo mesto where more then 600 Urn graves from the 3rd and the 2nd Century B. C. were found.

Biological continuity is not the only authoritative factor for the determination of national identity. The river remains the same despite the adding of other waters.

***

Page 21

Urns with cremated remains of the dead from the 2nd Century B. C. were found in graves at Kapiteljska njiva in Novo mesto that seem of Celtic nature due to added items. However urnfield burials in particular confirm the presence of Venetic Culture.

(Dolenski Museum in

Novo mesto)

It is not valid evidence to attribute a certain origin or culture to the dead by items found and on the grounds of separate items in the grave. It is necessary to consider all the evidence.

(Ralph Pollath in his book ‘Slovenia in sosednje dežele med antiko in karolinško dobo - Začetki slovenske etnogeneze’, Page 1011)

***

Page 22

In the history of Veneti, the Este Culture plays a primary role. It concerns the continuation of the Urnfield Culture burials, but with a difference, where, in Este Culture the Veneti developed their script and left for their descendants the legacy of invaluable monuments with many inscriptions, mainly in Italy, where the center of the Este Culture was, but in addition also in Slovenia. The little city of Este (Ateste) is near Padova and it was a religious center and also a school for writers. The Venetic inscriptions are the greatest proof that Venetic language is of a Slovenian character.

The inscription from Idria near Bače

(Museum of Natural Science in Vienna)

***

Page 23

Idria near Bače and Most na Soči (Sv. Lucija) was one of the prime centers of

Venetic Este Culture, as is evident from the large number of graves. 6500 Urn

graves found there, 1500 in Kobarid and 458 in Tolmin. The settlement

Most na Soči had its graves on the other side of Idrijca river, on a large terrace.

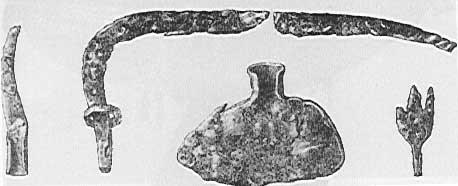

The Venetic scripts are from Idria near Bače.

|

|

|

Farm tools from Idria near Bače indicate an

uninterrupted farming culture on the Slovenian territory. (Museum of Natural

Science in Vienna)

***

(Museum of Natural Science

in Vienna)

Farming tools from Idrija near Bače testify to un uninterupted farm culture in Slovenia.

Page 24

Extension of Este Culture

The Este Culture was spread over the whole of present day Slovenian territory and was interwoven with Hallstatt Culture. We must also attribute many situlas and other items in the style of situlas to Este Culture as well as Venetic inscriptions found from Škocjan na Krasu to Negova. One such item is the ciborium from Magdalenska gora near Šmarje from the 5th Century B. C.

(The National Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana)

***

Page 25

The Inscription of Škocjan

OSTI JAREJ (Ostani mladenič = Stay Young)

A toast on the situla or jug from Škocjan na Krasu (on the Karst). Even though the inscription dates back more than 2000 years, it sounds very similar to modern Slovenian. ‘Osti’ means ‘Stay’, still ‘Ousti’ on the Karst to-day.

‘Jar’ is a well-known Slovenian word meaning ‘Young or New’. The noun form ‘jarej’ is still used in Charintian dialect.

***

Page 26

From the Occupation of the Slovenian Territory to the Disintegration of the Roman Empire

From the 1st Century B. C. to the 5th Century A.C., the Romans occupied the Slovenian region and brought with them their own language and culture. The indigenous population maintained their culture and language outside urban areas where it survived ready to be renewed following the departure of the Romans.

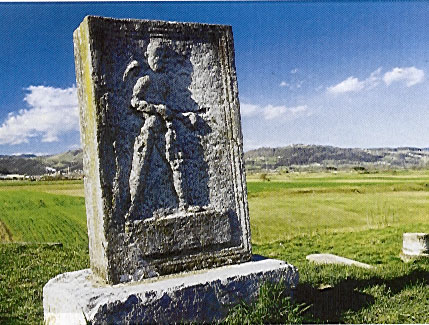

Part of a Roman headstone that is built into the wall of the parish church at Leskovec near Krško and the replica stands in the field near Drnovo (Neviodunum).

***

Page 27

Latinization did not Include Slovenian Regions

During the Roman reign, the Slovenian population retained their own language. At the fall of the Roman Empire, Roman language and culture had barely reached Furlania (in Italy) where the Slovenian language, in the country, was still in use right up to the Early Middle Ages as reported in Furlania by two historians from the 17th Century A. C., Matcantonio Nicoletti amd Giovanni Francesko de gli Olivi.

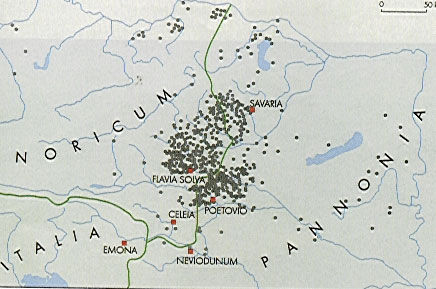

The ancient population

in the remote parts of the city regions of Petoviona, Flavia Solva and Savaria

was burying cremated remains under earth mounds.

The details about the expanse of the burial mounds were collected by Stanko

Pahič. (The Book 'Zakladi tisočletij')

As we discuss the Slovenian territory we must know that Romanization was only superficial. Except in the cities Emona, Celeia and Petovio there are very few Roman traces.

(By Adolf Lippold in his book 'Slovenija in sosednje dežele med antiko in karolinško dobo - začetki slovenske etnogeneze', Page 967)

***

Page 28

Elevated Settlements

During the disintegration of the Roman Empire various army bands were attacking Italy across the Slovenian territories. For this reason the population from the easily accessible locations moved to higher located grounds. It is obvious that they were the original inhabitants but it is false to say that they were Latinized even though it is possible that among them there might have been some Romans that have not been able to return to Italy yet. The valley of Vipava, that was mostly threatened, is an obvious example. Who else but Slovenians would have returned to the valley after the threat? Had they been the original Latinized inhabitants the Vipava valley would have become 'Italian' long ago.

In Late Antique period the trend for settling moved from the level plains and from along the traffic routes to concealed areas and well protected hills. One of such place is Polhograjska gora (mountain) where there was a well-strengthened settlement between two hills in the 5th and 6th Century A. C. (From the book 'Zakladi tisočletja')

***

Page 29

Military Settlements

We should not confuse military bases and their attached colonies with the settlements on elevated sites by which important traffic routes and important towns were controlled. In Slovenia we know of six such military forts one of them being Ronocov grad (castle) near Kobarid.

Ajdovski gradec (castle), above Vranje, is located in a difficult to access mountainous region that was always occupied since Roman times. The location was strategically well chosen because from the northern and eastern side it was well protected by the steep ridge of Mount Bahor. From the book 'Zakladi tisočletja')

There was no eviction of Romans from Slovenian lands and because of this the Roman way of life slowly disappeared. For this reason the Romans also had a lasting influence on the population of Slovenia.

(Adolf Lippold in his book 'Slovenija in sosednje dežele med antiko in karolinško dobo - Začetki slovenske etnogeneze', Page 967)

***

Page 30

Catholicism and the Disappearance of Diocese

In the 4th and

5th Century Catholicism was spread only among the Roman population, especially

in the towns, and died out with their departure. The diocese died out

because there were no believers and there is no trace of any missionary work

among the local population either. This is the reason for the disappearance

of the diocese rather than because of some assumed arrival of Slavs in the 6th

Century. The Slovenian population later accepted the Catholic faith with

the assistance of the Romans who did not depart and slowly integrated with the

local population. It is most likely that Kancij, Kancijan and Kancijanila

were already Slovenian martyrs.

(See the book 'Slovenci - kje smo...' Page 84 to 85)

The graves are mostly situated

in hilly terrain, usually on the crests of mountains. Most of them are

small (with a diameter of 6 to 13 meters, the largest (has a diameter of 25

meters) and they are often isolated but with vaults that contained valuable

additions. It is most likely that important persons were buried in them.

In the picture we see graves near the village Gerinci in Prekmurje.

(From the book 'Zakladi tisočletij')

Page 31

Why are there no Venetic Inscriptions in the Roman Period?

With Roman occupation, Latin became the only written expression of public life, not only on the Slovenian territories, but everywhere where the Romans ruled. Latin remained the only written language all over Europe even after the fall of the Roman Empire right up to the 9th and 10th Century. It is interesting to note that the first written folk-language that appeared in Slovenian liturgical books was in the 'Brižinski spomeniki'. However even older are Slovenian inscriptions from Čedad. All this presupposes an ancient written tradition. The simpler Latin script that developed from the Etruscan and Venetian script also helped to spread Latin.

The First lines of Brižinski spomeniki and its Reading

GLAGOLITE PONAZ REDKA ZLOUEZA

***

Page 32

Veneti in Noric

Veneti are the only confirmed indigenous people in Noric as well as Slovenia where Celts only came late after their return from Greece. They settled only in some regions and therefore left few traces. When the Romans took Noric there was no trace of the Celts and less later. After the departure of the Romans only Slovenians with the name of Veneti appear.

Gurina (Gorina) the once elevated settlement in Charintia was a well known name in Roman times. Artifacts found, including peaces with the Venetic script, indicate that for the Veneti Gurina was a trading centre. (The Natural Science Museum of Nova Gorica).

The Change

After the disintegration of the Roman Empire in Slovenian territory, other temporary military forces appeared until the region was finally occupied by the Franks and later transferred to Habsburg's reign. In all this time the Slovenian people proved their firmness that was finally crowned in 1991 with a free and independent Slovenian state.

Signs of life and hope

A bronze fibula in the form of a cross from Tonovcov Castle near Kobarid, 6th Century A. C.

(Goriški Museum in Nova Gorica)

***

Page 33

About the Name Veneti

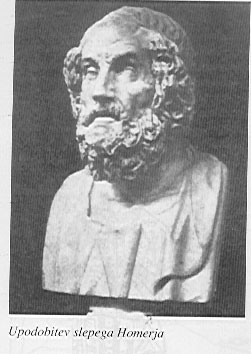

If Veneti are the ancestors of Slovenians why are Slovenian not called Veneti? The original name was most likely Slovonci or Slovenci (Slo-venci, Slo-veneti). Because the Greek language does not have a sound 'sl' and has no letter 'v', Homer amongst other Greeks shortened the name to 'Enetoi'.

According to Plinii this name was also adopted by the Latin writers, however with the letter 'v' but without the letters 'slo' because Latin also lacks the 'sl' sound. In Venetic scripts the name Veneti is not used, but the name Slovonici is used if we substitute the letter 'i' for the letter 'l'. In this context the important word 'slovo' (word) appears and gives it the meaning, namely that Slo-veneti are people of the same word or the same language.

A statue of Homer already blind

The name S(l)ovonici on a handle from the find in Karnitian Alps.

***

Page 34

Testimony

Historical statements and language traces show an uninterrupted existence of Slovenian ethnicity and Slovenian language during the Roman period. The fabricated theory of 'latinized aborigines' has no valid base.

Slovenian names are known from the Roman period e.g. Trgeste (tržišče=market), Oterg (otržje), (Dravus Drava=river), Saloca (Zaloka)=village), Longaticum (Logatec=town), Poetovio (Ptuj=town), Ad Pirum (Hrušica=village) etc.

After the departure of the Romans and later of the Bizantinians in the year 568 there is a historically confirmed Slovenian state in Noric that was attacked and plundered by the Bavarians in 593 and again in 595. Some so called historians claim that at that time the Slavs just arrived at their present location.

Reliable witnesses:

St Jerome, who around year 400 enthusiastically translated Slovenian writings to Latin.

St Severin, who around year 480 sought remnants of the Roman population among the indigenous people in Noric.

Historian Jordanes, who writes around year 551 about 'Slevene’ and other Slavs.

John Babbiensis, who around year 612 in the life-story of St. Columbus specifically names Slovenians as Veneti.

Fredegarii Cronicum, who often names Slovenians as Vinedi (Veneti).

Paul Diacon, who mentions nothing of the settlements of Slavs during the end of the 6th Century, even though he mentions the minutest details of his period right up to the border with Longobards.

Stature of Paul Diacon from the 11th Century.

***

Page 35

A Remarkable Statement

In the historical records a remarkable statement by the Gothic historian Jordanes is of special significance concerning the presence of Slovenians in the Roman period wrote: 'On vast planes lives a numerous nation of Veneti.' He divides them into Ands and Slavs. About these he writes: 'The territory of Slovenes reaches from the town of Novietum and from the so called Mursian Lake to the River Dnjeper and up to River Visla to the north.' In these words we can best see the description of all Western Slavs, from Slovenians to Slovinians along the Baltic. Novietum can only be Neviodunum, today’s Drnovo near Krško, at that time an important Roman centre and a port on the river Sava. Marsian lake can only be Blatno jezero (Boloton Lake) named Mursian because of the nearby river Mura.

Jordanes wrote in the year 551 referring to year 490. This was some one hundred years before the Slavs were supposed to have settled in present day Slovenia in the region of the Eastern Alps.

The map shows a grid of Roman state roads (via publicae) and other roads in Slovenian territory. The thick lines indicate roads that are documented in the archives and the thin ones are assumed roads only. (From the book 'Zakladi tisočletij')

***

Page 36

In a few Words

A horn in the shape of a bird

from the 9th Century B. C. A herald of the new times (NMS

in Ljubljana)

With the arrival of Vends the Slovenian nation came into being three thousand years ago.

From the Knežji kamen echoed only the Slovenian word.

One thousand five hundred years later the Slovenian nation reveals its democratic character which was previously unknown in Europe.

After three thousand years new horizons are opening for the Slovenian nation.

The Slovenian nation free and independent builds its own future.

***

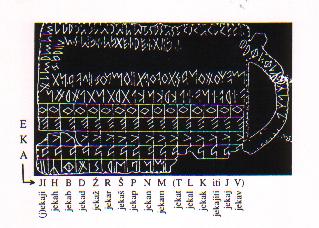

Back Inside Cover

The Slovenian language is a continuation of the language of Veneti that is not only proven through irrefutable etymological similarity but also with the distinctive grammatical similarity that is evident on the attestation tables.

In the first part of the table are ten verbs in the participle form that are all still in use in the Slovenian dialects.

L PRPN P L ŠRŠN Š L ZRZN Z L KRKN K L BRBN B L GRGN G L KRKN K L TRTN T L DRDN D L MRMN M

There can be no doubt about the distribution because every word is limited by the previous letter L and with repeating of the second last letter of every word some kind of an echo comes with reciting.

The second is a votive sentence included in the scope of the mentioned words.

In the third part we find six forms of the verb jekat (jokat=to cry) that are still in use in the Slovenian language today.

The

last six missing letters on the table are substituted with the letters of another

table because of the damage to it.

(See the book 'Slovenci - kdo smo?' Page. 58-63)

SUMMARY from the Book 'SLOVENCI' by Ivan Tomažič, Ljubljana, 1999

We experienced a major surprise in 1991 when in the Tyrolean glacier Similaun, above the village of Vent the body of a man appeared from under the snow. Although more than 5300 years old, it was in remarkably good condition. Who was he? What was he doing up there? How did he die? What kind of belongings did he have with him? These and other questions were frequently asked at that time. I was most interested in the question asked by a linguist: "What language did this man speak?"

Is it at all possible to know the language of the oldest European, called Oetzi by Austrians, after the Oetz Valley? The well-known Austrian writer, Dr. Gunter Nenning, wrote in his article: Oetzi ist ein Slowene / Oetzi is a Slovenian, and that the Veneti were the oldest known people of the area, considered the ancestors of Slovenians. The article was reprinted in the book ‘Der Mann aus dem Eis / The Man From the Ice', by F. Graupe, and M. Scherer. He concludes by saying: "Oetzi is a Slovenian. Is this possible?"

Europe had till the end of the last Ice Age (around 10.000 year ago) only a small population; in the first part of the Middle Stone Age the population increased modestly, in part due to the influx of people from the Sahara. Their survival still depended on hunting and gathering of edible plants, which involved considerable movement of people from one location to another. The mixing of people would have maintained a certain uniformity of language, and the dialects would have enriched the common idiom, which could have remained very much the same for thousands of years over the broad expanse of Europe. However, with the advent of agriculture, people were forced to establish permanent home bases in fixed areas, in defined groups, where language variations gradually evolved.

Soon after occurred the Indo-European phenomenon with its social and language changes. The initial uniformity of the language gradually gave way to new forms of expression. At the core of the action, in central Europe (Corded-pottery culture) a new language developed with strong residual elements of the original. The transformation carried on into increasingly wider territory, with progressively less dependence on the pre-Indo-European language.

In only one direction was the Corded-pottery culture of the Indo-Europeans not able to spread, and that was across France to the Pyrenees. That region's original pre-indo-European language survived and underwent further changes from within. This is only the Basque language, which allows us very interesting comparisons.

Let us look for similarities between Basque and the Indo-European languages. We will find them above all in Slavic languages, and particularly in Slovenian. Since the Slovenian language has never been in contact with the Basque, we must conclude that the similarities originate in the distant pre-Indo-European past when there was a common language from the Pyrenees to the Alps and beyond. We have already examined these similarities, limiting ourselves to the most obvious elements. However, linguists also discovered complex morphological similarities between the two languages. Many words reveal their pre-Indo-European origin. They belong to the period of the original common language that we named Proto-Slavic, from which, under Indo-European influence, developed the new Slavic language, Venetic or Slovenetic . The formation of this language represents the demarcation line between the pre-Indo-European and Indo-European period.

The users of this language belonged to Urnfield Culture cremating the dead. The ash urns were interned in extensive burial-fields. Some scholars object by stating that cremation of the dead was known in other places even earlier. However, this in no way diminishes the importance of the Urnfield Culture, its dimension, and its religious significance.

It is generally agreed that the spreading of the Urnfield Culture started within the Lusatian Culture, although there is a certain fear on the part of historians (this is of no importance to archaeologists) to name the bearers of this culture, because they know of the background presence of the Sloveneti. The name Veneti originates in Sloveneti or Sloven(e)ci, and appears first among Greeks (as Enetoi), only after the end of the Urnfield migration.

Along with the Urnfield civilization, there is evidence of a parallel spreading of the Slovenetic language along the Danube to Asia Minor and to India, where the Sanskrit language established itself. Sanskrit has remarkable similarities with Slovenian as evidenced by the book VEDA, the oldest book in the world, whose title has the same meaning in Slovenian as it has in Sanskrit. There were two other routes used by the Urnfield people for dissemination of their culture and language. One led along the Atlantic coast from the Baltic to Armorica, where there are, or were till recently, remnants of Slovenetic language. The most important route was the Amber Road, which connected the Baltic with the Adriatic.

Of particular importance, in regard to the Amber Road, is evidence that the dissemination of Slovenetic language paralleled that of the Urnfield Culture, also proving beyond doubt, that the bearers of the Urnfield Culture were Sloveneti. Let us look at this important evidence, with which we Slovenes are directly linked.

Archaeological finds in Slovenia show strong settlement of the Urnfield Culture bearers near Maribor (Ruše), Ljubljana and its vicinity, as well as other places as early as the 12th century B.C. This means that present-day Slovenia was a centre of the bearers of the Urnfield Culture on their Amber Road, as shown by numerous finds suggesting a lively trade between this and other centres to the north.

It follows that the Urnfield Culture arrived in Italy from what is now Slovenia - proven for the 11th century B.C. Sloveneti also turned from the Amber Road into Austria, where major urnfields were discovered near the city of Hallstatt, which gave the name to the new culture. It was within Hallstatt Culture that the Celts evolved and ruled over large parts of Europe for a time, until they disappeared. They had no permanent domicile anywhere.

A separate chapter belongs to the bearers of Urnfield Culture in Italy where they are known as Veneti, Rhaetians, and Etruscans. The centre of Rhaetian culture was called Golasecca, the location of important Urnfield finds.

The main stronghold of the Urnfield Culture in Italy developed between the eastern section of the river Po and the Alps where the Este Culture blossomed on the foundation of the Urnfield Culture. It is this culture that left us the Venetic inscriptions, the most prized monuments of our ancestors. Similar to the Venetic inscriptions are the Etruscan and the Rhaetian inscriptions. They all show a connection of the language of that time to modern Slovenian language. The evidence of the Venetic inscriptions, which can be understood only with the help of the Slovenian language, is further strengthened by numerous names of places, rivers, and mountains throughout northern Italy, Switzerland, and Austria. They demonstrate that people who spoke the Slovenian language lived at these locations.

That these names are Slovenian not only in form but also in sense is demonstrated by the words themselves, which have no meaning except in Slovenian. Interesting are the place-names with twin names; that is, the original Slovenian name preceded or followed by the Italian translation, as in Ponte Mostizzolo (Slov. mostiček is preceded by translation Ponte); Peschiera Sabbioni (Slov. peščina is followed by translation Sabbioni); Calalzo Lagole (Slov. kalce is followed by translation Lagole). Many Slovenian names in Italy and in Switzerland are often found also in Slovenia; for example, the mountain name Schijen, which is found four times in Switzerland, is even more numerous in Slovenia as Sija. The same is true of place and stream name Roia in Italy; in Slovenia it is Roja, a name of several places and streams.

Under the pressure of the Roman Empire the original Venetic presence has gradually receded eastward to Friuli, where the Slovenian language is documented as late as the Early Middle Ages. The Romans and the Goths, after them, have exterminated Rhaetians in bloody campaigns, but in the areas north and east of Friuli the original Venetic/Slovenian population survived. There, Roman rule was not able to change the language and the character of the indigenous population. Thanks to its special position within the Roman state, the Slovenian population in Noricum also remained unchanged. After the collapse of the Empire and after the departure of Byzantine occupation forces in 568, Noricum became the independent Slovenian state, Carantania. For several centuries it united Slovenians until it was absorbed into the Frankish-Hapsburg Kingdom.