Nilotic Spirituality and Philosophy

Some of the oldest spiritual beliefs known to man emerge in Eastern Africa along the Nile Valley. To understand the religion of the Nile Valley, where Egypt rose to greatest prominence, Egyptologist E.A. Wallis Budge stated one had to understand Africa. Beyond dress and art, no other relationship stands out more between Egypt and Africa than in the area of spirituality. Many of Egypt's belief systems can be traced back to inner Africa itself. Cheikh Anta Diop wrote, "Negro cosmogonies, African and Egyptian, resemble each other so closely that they are often complementary. Such similarities include the following: the use of zootypes (animals) in religious figures; the veneration of ancestors; the emphasis on cattle cults found throughout Africa, especially East Africa; the notion of the god-king; etc.

|

Certain religious rituals now extinct in Egypt are still practiced in such regions as Somalia. And these spiritual belief systems form the basis of Egypto-Nubian philosophy. Nubian archaeologist Bruce Williams states, "The way of looking at the world to be found in, say the Hebrew Bible or in Babylonia literature or amongst the Greeks is very different from anything you find in Egypt. And that difference is its Africaness." To fully discuss the cosmological complexities of this region's spiritual system and their relationship to Africa would take volumes. Thus below only a few points will be touched upon. |

|

Understanding the spiritual beliefs that permeated Egypt, Nubia and the Nile Valley must begin with an understanding of their concept of deity. In Egypt there existed a host of deities each of whom were thought to affect the universe. Some of these were Auset, Ausar, Ra, etc. However these deities were not exactly thought to be separate from each other. All existed in conjunction with the other, sometimes even blending or usurping another's role. Take for instance Amen-Ra. Both were "separate" deities whom the Egyptians wasted no time in placing together. The reason deities could so easily be placed together to form a new deity was because of the African law of interconnectedness between deities. The interconnection of these deities easily lent itself in Egypt to the idea of a single God deity. This all-powerful and faceless deity was called at times Neter. The many manifestations Neter took were called the neteru: Auset, Ausar, Ra, etc. This can be found in a host of African spiritual systems where a supreme being is regarded as the "Creator" or "Chief Deity" among others. The example of Oldumare's supremacy in the Yoruba pantheon is a prime example. The move to a more extreme form of monotheism was attempted under the Egyptian ruler Akhenaton with less than successful results. It would seem the Egyptians, like their African counterparts, liked their many manifestations. |

|

Many of these neteru were thought to have once been rulers or wise men. The "Souls of Neken," legendary predynastic rulers worshipped in Egypt, are now known to have actually existed. This idea of ancestral worship is found throughout Africa. Many African people impute the souls of dead ancestors a godlike ability to bring good fortune or dire consequences. The souls of dead kings are said to be especially important. In Yoruba the Orishas are said to be ancestral spirits, many of them past rulers, whom determine human life. In Uganda, kings are believed to continue watching over their people long after death. Special temples are even built through which their spirits can be consulted for advice. Pictured is a statue from ancient times of the neteru deity Ausar, believed to be the first king of Egypt who ascends to godhood. |

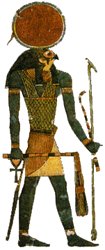

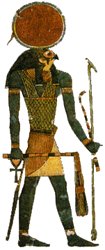

Ausar, commonly known by his Greek name Osiris, was one of the most famous neteru in Egypt. Heralded as the first king of Egypt it is believed Ausar is a composite of long dead kings who lived in ancient times. He is credited with bringing "civilization" to his people and establishing a code of spiritual laws and moral standards. The story of Ausar is a long and complex one. It is said that he ruled Egypt with his wife Auset, who is better known by her Greek name Isis. According to legend, Ausar was slain by his jealous half-brother Set, who cut his body into fourteen pieces. He was eventually resurrected and ruled in the underworld. This documents the oldest belief of resurrection and immortality in human history. And similar stories of slain and immortalized god-kings can be found throughout Africa. As old as 2,000BC the Khoi of southern Africa held that Tsui was the first chief who is killed by a nemesis, Gaunab, only to be resurrected repeatedly to retire and rule in the "beautiful heaven." Among the San, Cagn is the god-chief who is killed in treachery but achieves resurrection. Pictured here is Ausar in his role as the deceased king which all Egyptian rulers wished to become upon death. |

Typical of African deities, Ausar had a known consort, Auset. Auset (Isis) was the wife and sister of Ausar. Like her husband, she was thought to be an ancestral spirit. Heralded as the Queen of Egypt, Auset was said to be responsible for bringing writing and agriculture to the people. She also symbolized the fertility of the land. One of the original 9 neteru of Creation, it is said that she gained her power by learning the secret name of her father Ra. Following her husband's death, Auset searched the land for him. She found his body only to have Set dismember it into fourteen pieces. Once more she searched for her husband and located all of the pieces of his body save his phallus. Auset created the tekhen (obelisk) to symbolize her husband's missing member. With the help of the neteru Tehuti and Anpu, Ausar was resurrected. Legend further goes to say that while her husband was dead, his spirit entered and impregnated her. Shortly thereafter she conceived a child who would be named Heru. This act represents the first immaculate concepetion known to mankind. Auset's worship would remain for several thousand years up to Rome where her temples became numerous. Pictured here is Auset with her son Heru. |

| Heru is the immaculately conceived son of Auset and Ausar. At his birth it is said three wise kings or Magi came to honor him while he was adored by all manner of neteru and men. As an adult, Heru avenged his father by triumphing over his wicked uncle Set. Heru then journeyed to the underworld where he sits with his father in judgement of the dead. Heru's triumph over Set is the orgin of the word "hero" and his association with the zodiac makes him the source of the world "hour." Thus the minor deities of the zodiac are the "Watchers of the Hours (Horus)" or horoscope. He is depicted as a falcon or a man with a falcon head. Heru became known also as the "child of the light" representing the sun (knowledge) driving away darkness (Set; the setting sun; ignorance). From the earliest times in Egypt he came to represent the living king or divine kingship. This idea of the king as nearly a living god typifies African ideology and is thought to have come up the Nile from the south to Egypt. In fact it is said in Egyptian texts that Heru invaded Egypt from the south. Pictured here is the falcon headed Heru.

|

With this belief in a god-like king came the association of the king with the land. Thus while a powerful king ensured the land's prosperity, a sick or weak king foretold its demise. Many believe the kings of prehistoric Egypt were put to death when they became sick or weak. This unique practice was known in many African societies such as the Sofala whose king was required to commit suicide when he became weak. Ritualistic-symbolic death eventually replaced the actual practice and can be found among the common day Yoruba, Dagomba, Shamba, Igara, Songhay, the Hausa of Gobir, Katensa, Daura and Shilluk to name a few. |

Originally called the Her-em-akhet (Heru of the Horizon), the immense statue commonly known as the sphinx symbolizes several key Egyptian concepts. Symbolically the lion portion of the statue represents the animal nature and raw chaotic power within mankind. The human head represents the intelligence needed to ascend above the animal power and use it wisely to rule and bring divine order to chaos. Thus the blending of these two opposites brings about harmony. Also depicted is the ability of mankind to rise above his chaotic nature and ascend to divinity. Here once again are the African concepts of opposites.

|

Also within the Her-em-Akhet is the association with the divine kingship as the statue also represented the power of the ruler. The head of the statue is none other than the ruler's very symbol, Heru. The lion portion symbolizing strength is well known throughout Africa. In Nubia the lion-headed god Ampedak was revered and the king depicted as a conquering lion is found repeatedly within Egypt. Pictured above is the Nubian Queen Amentari and King Netek-amen worshipping a three-headed version of Ampedak.

|

| No discussion of Egyptian cosmogony would be complete without alluding to Ma'at who best represents the ideas of divine order so common in African belief. Pictured as a woman with extended wings, Ma'at is associated with seven cardinal virtues: truth, justice, propriety, harmony, balance, reciprocity and order. These virtues, along with 42 other laws, correspond to the divine order by which the

universe---from the common person to the neteru--- must abide.

|

| Het-Heru (Hathor) was not only a consort of Heru but one of the most important deities in Egypt. She is regarded as the neteru of beauty, joy and love and is associated with life, health and fertility. She is especially important because of her bovine attributes. The usage of animals to depict deities, a common African practice, is well illustrated in Egypt. A feature that permeates much of Africa, most especially the Nilotic region, is that of cattle culture. As early as 6,000BC the southern Sahara yields depictions of a cow horned goddess delivering food and life to mankind. This attachment to cattle comes from the very heart of Africa. As early as 9,000BC Nilo-Saharan peoples were domesticating cattle. These Nilotics steadily moved up the great river to found the Egyptian and Nubian cultural complexes. Pictured here is the Egyptian Het-Heru as a cow figure.

|

Among the Ugandans anthropologists noted how chiefs would moan over the loss of cattle as if it were their child. The same attachments are found among other cattle culture groups in East Africa such as the Nuer and Dinka. Cattle culture rituals seen among the predynastic Egyptians are today still practiced almost to the point of perfection by these Nilotic groups. The Egyptians' love of their bovines is well documented among households who built special rooms for their animals in life and elaborate funerals for them in death. The first king of Egypt, Narmer (Menes of the Greeks), displays Het Heru on his standards. Cattle culture and divinity also play great roles among the later West African empires, as in the Sundiata legend, and among the Zulus. The mask above was found in the Sinai, displaying the spread of her cult outside of Africa. Also of note is Het-Heru's powerful opposite personality of the lion-headed goddess of battle called "the fiery eye of Ra," or Sekhmet.

|

There is probably nothing more quintessentially Egyptian than its cult of the dead. Interestingly enough the ancient historian Diodorus attributes this belief to the Ethiopians from whom the Egyptians are said to have learned it. It is in the Egyptians particular care of the dead and its deceased ancestors that it seems most African. It is often erroneously stated that the ancient Egyptians had a morbid fascination with death. More accurately stated, like other African ethnic groups, they felt they had a strong connection with the spiritual world. Thus preparation was made throughout one's life for the afterlife. This can be seen in the elaborate funeral rites and mummification that nearly every Egyptian, regardless of social status, sought to acquire. This interest in preparation for the afterlife was not a part of the Mesopotamian or Mediterranean world, but rather an attribute very strong in Africa. Many African peoples did in fact mummify their dead. Some would smoke-dry their dead and wrap their bodies in cloth to preserve them. As in Egypt, the eternal organs were removed. When Sonni Ali, emperor of the West African empire of Songhay died, his organs were removed and he was filled with honey. Pictured above is a figure paying homage to the pantheon of the deceased.

|

| Pictured here is the jackal headed Anpu leading a man, Ani, to judgement. Anpu is associated with funeral rites and was instrumental in mummification. Notice he holds here in his hand an ankh, a symbol of life, though in the underworld. This represents the eternal aspects of the soul indicating that death was simply another form of life. Before all was done Ani's heart would be weighed by Ma'at to determine his good deeds and his soul would be judged by none other than Ausar. This benevolent view of the afterlife is very common in Africa. It is in direct contrast to the early ideas of death in Western Asia and the Mediterranean where the dead either existed as gloomy spirits or subsisted miserably for eternity on dust. Interestingly the Dogons of Mali also have a jackal headed deity. He is regarded as the guardian of the pond where the dead reside. (Photos and Information courtesy of African Origins of Civilization by Cheikh Anta Diop, Black Spark, White Fire by Richard Poe and Egypt in Africa by Theodore Celenko, Egyptian Book of the Dead trans. by EA Wallis Budge and Reeder's Egypt Page)

|