Italian painting, CIRCA 1360, (Thought to be oldest pourpoint image known) |

Detail of Prisoner, Allegory of Good Government (Fresco), 1338-40, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena |

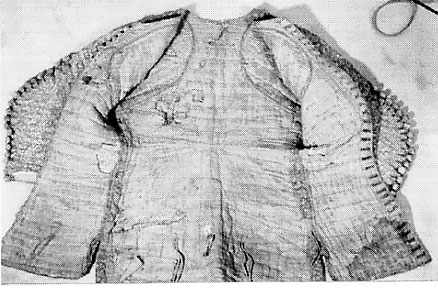

Photo taken at Musée Historique des Tissus de Lyon, showing quilting pattern. |

The characterizing factor of the 14th-century pourpoints was its form fitting construction primarily in its forearm region. The sleeves were loose in the upper arm and cut quite narrow in the forearm. The closer the fit at forearm, the more numerous and extended the span of buttons required to close them became. By the turn of the 1400’s, this trademark sleeve had primarily become a more uniform, loose taper minimizing the need for buttons or lacing. In 1450 mahoîtres (puffs) were added to the shoulder joint of the sleeves.

The entournure of the sleeves, or grandes assiettes, eliminate all seams that distinguish between the arm and shoulder. As with the form fitting nature of the remainder of this garment type, wearer’s whished to have the entournures match the body’s aspect to the greatest possible extent. The result is a vestment that allows for full circular movement of the arm.

Collars were not a common characteristic notated on civil under clothing and pourpoints of the first quarter of the 14th century. It wasn’t until the miniatures and statues of the doubletiers of 1323 that researchers found consistent and definitive proof of their use. In the 1370’s pourpoints collars evolved to a stiff, moderately height fashion. In 1390 these collars began to be embroidered in faux mesh, coins and real mesh (mail). The purpose of this practice is believed to be to give the illusion of the wearer having some form of body protection under one’s clothing to discourage attack by adversaries. Until falling out of vogue in 1410, excessively high collar were seen on garments such as houppelands, but never so defined on pourpoints. After about 1415 a rising collar, called a collet, was a standard amenity on the neckline of the majority of pourpoints. These collets were segmented and stuffed to a ridged form as the piqué described above, though not as thickly packed. Examples of high stiff collars remained to be through 1440 and beyond.

Closures were either buttons or laces. The coat of Chartres (of the age of king Jean le Bon, 1319-1364) is buttoned while those from the time of Jeanne d’ Arc (1412-1431) are generally laced. A lace of 20 millimeters (or roughly ¾ of an inch) was commonly used, though the width varied according to weather “button holes” or eyelets were used to run the laces through. Buttons on the pourpoint of Charles de Blois are fabric-covered wood. Thirty-two buttons fill the thirty-four holes on front and twenty more span each sleeve for a total of 72 buttons. Close examination by the restorationist at the Musée Historique des Tissus de Lyon reveals there is no sign the two missing buttons were ever on the garment.

Two main variants of pourpoints were known to exist in the 14th century. The first was meant to be worn under harness (armor), usually post scripted by ‘to arm’, and the second for civil use, occasionally post-scripted by ‘to vestir’. Both versions of the pourpoint were expertly tailored to the wearer’s body. I have recently stumbled upon a statement that to arm pourpoints are quilted vertically while to vestir are quilted horizontally. I have not had the time to verify the validity of this statement, but it would make sense knowing the Charles de Blois pourpoint is a to vestir type and quilted horizontally while the “coat armor” of Charles VI is quilted vertically.

Originally, this garment was worn as an under shirt. It was not until the 1340’s, when the fashion of short clothes became more prevalent, did pourpoints began to show from beneath. The fabrics used in their construction began to move towards the richer end of the spectrum since they were becoming more and more visible. This fabric change started on the sleeves and skirt edge, and moved throughout the entire garment in a relatively short period of time. By 1415 the pourpoint’s shift to an external garment was completed and therefore was extremely rare for pourpoints to be seen as undergarments.

General Fabrication:

This pourpoint is constructed of fourteen panels while the original was composed of twenty wight total. I chose to minimize the number of panel on this garment because my intent in making it was to test fit my pattern. In period, fabrics did not come as wide as they do today and so there was a need for more pieces to span the same distance. When I make my final recreation pourpoint, I will add these extra panels back in as they only serve an aesthetic proposes and bear no effect on the fit of the garment. I also omitted the seven pairs of points for the attachment of hose for the same reason as above. The next version I plan to make will be a quilted on. The spans between the De Blois quilts are 35 mm apart and I see no reason not to keep this distance intact. I have learned it must have taken a degree of science and skill that few tailors of our time could reach to design this style of clothing. It truly is a marvel of tailoring. Sources: History of Costume by Milia Davenport Musée des tissus et Musée des Arts décoratifs de Lyon 34, rue de la Charité, F-69002 Lyon - France Vincent Cros (Bibliothèque Centre de Documentation), Sonia McCarthy-Baron (Banque Image) and Marie Schoefer (Exhibit curator for the Pourpoint de Charles de Blois) Atelier de Restauration et de Conservation: Musée Historique des Tissus de Lyon, Rapport de restauration by Schoefer, Marie (Report of restoration: May 1981) http://site.voila.fr/costumexv 1 "Jeanne d'Arc, ses costumes et son armure" By Adrien Harmand, Paris, 1929 online copy The Pourpoints of: Charles VI (dolphin), Chartres, and Edward, The Black Prince, Canterbury. 1 Special thanks to Guilleaume Defay, who visited Musée des tissus et Musée des Arts décoratifs, to acquire my specific photographic and informational needs from the original Charles de Blois pourpoint exhibit as well as for helping me fill in the blanks in my translations of French reference materials.

Photo taken at Musée Historique des Tissus de Lyon, showing extra panel See full back view for further illustraition.

Photo from Atelier de Restauration et de Conservation. Musée Historique des Tissus de Lyon. May 1981, Marie Schoefer.

Photo courtacy of Musée Historique des Tissus de Lyon (Not authorized for duplication, so don't copy it!)

Copyright Terms, Copyright Wolfram von Taus © 2002, 2003, 2004