Because some aggregations of rust excavated at Nineveh are believed by experts to have once been hauberks of mail, this form of armor is believed to date back as far as the mid 600’s B.C.1 and remained in use well into the 18th Century. Incidentally the Nineveh aggregations are credited with being the earliest examples of true interlocking mail. From Asians to the Scandinavians, most cultures had some form of this armor in use at one time or another. While it is uncertain, historians hypothesized mail is probably of eastern origin. We do know however, it was not brought back to the west by crusaders as popularly believed, but was definitively in Europe as early as the 2nd century B.C..

There is a wealth of information with which we can trace the evolution of mail beginning with simple short sleeve shirts, through entire body suits, to its recession with the advent of white harness (plate armor). Brasses, ordinance lists, art of the times and archeological finds all combine to give a clear picture of the evolution of mail. The vast majority of archeological finds, such as those excavated at Wisby, show us iron (and later, primitive forms of mild steel) was the material primarily used in their construction. Much to the dismay of today’s re-enactors, bronze and copper were rarely used and brass was generally considered too soft to afford any real protection against the weapons of the day.

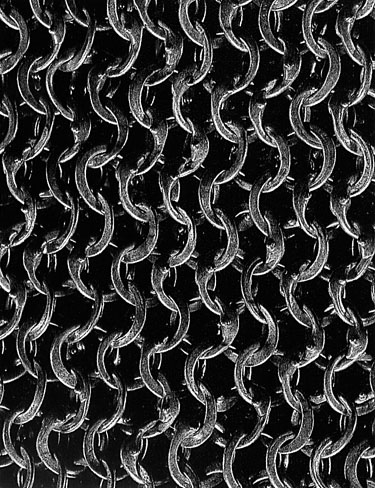

The majority of European fragments found consist of circular rings in a 4 in 1 weave. (This is to say that every ring in linked into four others.)

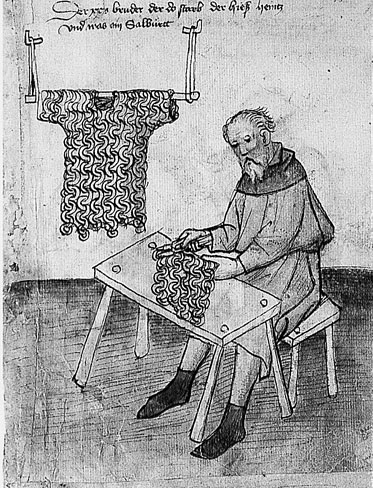

From Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung, German 1435-36, Stadtbibliothek, Nuremburg MS. AMB. 317 |

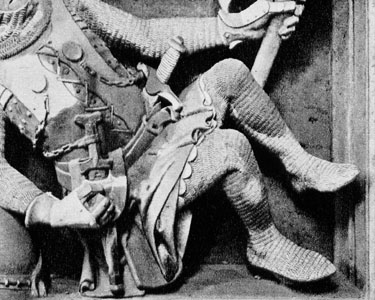

Hauberk Detail, European (Believed German) 15th C Cleveland Museum of Art CMA 1923.1120 |

1The city of Nineveh was overrun in 612 B.C. by allied forces of Babylonians from southern Iraq and of Medes from Iran.

European rings were always either riveted or solid. Butted rings are considered to be of oriental origins, though, according to Claude Blair, fragments found in the Sutton Hoo2 ship-burial (The British Museum) appear to be an exception. Solid rings were always found alternating with riveted until they appear to have gone out of fashion at the end of the 14th century. Riveted links, however, remained in use as long as mail itself. The primary theory for the change to all riveted construction is accredited to the expense of forging closed rings exceeding that of having apprentices rivet rings. The cost of mail was already so high only nobles and wealthy merchants could afford it and any cost reduction could only help sales. Late medieval ordinance lists catalog such styles as ‘flat’ mail, ‘round’ mail, “mail de haute cloueure”, “mail à grain d’orge” and the more rare, “double mail”. These terms relate to variations in the size and sections of the rings and rivets. The shape of the rings most commonly portrayed in sculpture is that referred to as ‘round’ mail implying it is formed of round wire. ‘Flat” mail, seems to refer to the result of using square wire to construct the rings. The size of the rings varied according to the time the armor was made and its designed use. Most sources that refer to ring sizes describe 13 to 16-gauge wire looped into rings measuring 5/16” to 1/2” inside diameter. (These numbers are approximations related to today’s measuring standards). Black oxide is a conversion of the top most crust of existing metal to a black form of rust. This finish provides very limited corrosion protection under mildly corrosive conditions and should be kept oiled. It is used mostly as a decorative coating and is done today with either mixtures of caustic soda, nitrate (sodium usually), wetting agents and stabilizers or from proprietary chemical mixes. In period a mix of lime, sulfur, charcoal and urine (usually from horses) is thought to have been used. The result of the process is a very thin, dark black iron oxide finish. It is believed by some that the armor of Edmund, Prince of Wales, was actually finished with a black coating. Although he was not given the name "the Black Prince" until after his death, it is possible that this represents a finish used during the 14th century. I am still researching this belief though it seems unlikely since there are hundreds of manuscript illustrations from the 14th century, and they almost always depict the armor as satin or gloss finished. This satin or gloss finish is presumably due to the polishing methods of the day. The most popular of which appears to have been to place mail into a barrel partly filled with sand and/or small pebbles. The barrel was then capped and squires rolled them to produce millions of ultra-tiny scratches on the armor. These scratches removed oxidation and polished the metal surface below much the same way as (rock) tumblers work today. There is a text describing a friendly competition between squires referring to "rolyng of barels" where they raced across moderate lengths advancing their masters 'armor polishers' towards a 'finish line'. Unfortunately, I have not been able to recall where I read it to cite the specific source. There are also several methods of hand polishing. An example of such is thoroughly rubbing the piece with linseed oil, which acts as a cleaner and rust preventative when regularly applied. Evolution: (from the mid 11th century to present day. Prior to this date there were no changes relevant enough to this project to merit mention. Two images are provided per significant notation; one showing a detail referenced to the specific time period, the other showing the same detail’s use in the mid 14th-century) Collage of details from the Bayeux Tapestry, 1066-1082

During the 15th century black finishes on armor become commonplace in manuscript illustrations. It is not clear whether this was an oxidized finish or paint. There is only one piece I know of, held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with a similar finish. It is a composite harness dated approximately 1480. It is possible this is not the original finish, but with museum documentation and restoration the way it is today (using infrared photography and countless other means of inspection), I believe it to be so as I noted no mention of the authenticity of the finish. While it is not likely that this finish is directly from the hammer, as the suit looks pretty smooth, it may be a result of heat treating or quenching in an oil bath.

2Sutton Hoo is an estate near Woodbridge, in Suffolk near which the burial site of a 7th century Anglo-Saxon king was found. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "The burial, one of the richest Germanic burials found in Europe, contained a ship fully equipped for the afterlife (but with no body) and threw light on the wealth and contacts of early Anglo-Saxon kings; its discovery, in 1939, was unusual because ship burial was rare in England"

1066-1082 Bayeux Tapestry: A majority of the figures depicted wear knee length shirts slit from hem to groin (for riding horses) with wide sleeves reaching just below the elbow. There is some likelihood that separate mail coifs are shown, but no other illustrations depict this style prior to the second quarter of the 13th century has yet been noted.

Upper Left: Attached coif. Lower Left: Possible coif with round mantle

Upper Middle: Possible coif with round mantle. Lower Middle: Attached coif

Both Right: Showing square neck to be part of hauberk, not a coif mantle

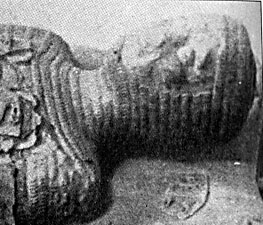

Effigy of Ugo de Cervellon, 1334 Hospitaller Church, Villarfranca del Panadés, Spain |

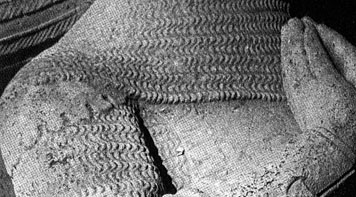

Effigy of Ulrich de Huss, 1345-50 German, Musée Unterlinden Colmar, France |

Late 1000’s: Towards the end of the 11th century, sculptures, illuminated manuscripts and seals show mail shirts with close fitting sleeves that extend to the wrists. This style never superceded the elbow length sleeve version.

1150: Illustrations begin to depict the use of mail chausses. The two most common forms of this leg protection appear to have been either a strip over the front of the leg laced into position across the back of the leg and under the foot or as mail stockings with a garter below the knee for support.

Goliath with chausse on leg fronts only, 12th C. Manuscript. Pierpoint Morgan Library of NY |

Image of foot soldier from Guardians of the Holy Sepulchre, 1345-1350, Freiburg in Breisgau Cathedral. |

It was also at this time that surcoats first appeared though armorial surcoats (i.e. surcoats displaying heraldry) were extremely rare until the early 14th century. There is still much debate as to the reason of the surcoat’s origin; some believe it to be a heraldic device, others say to keep water off one’s mail. Either case can, and has, made valid points both for and against one another.

1175–1200: During the last quarter of the 12th century, mittens (or mufflers) began to cap the long hauberk sleeves in sculptures and illustrations. The Winchester Bible (CIRCA 1199) possesses a unique illustration showing hauberks with sleeves extending over the backs of the wearer’s hands leaving the fingers and thumb bare. This is believed to be an intermediate step towards mittens. Many illustrations show the palm was not covered with mail, but rather with leather or fabric. This material was slit to free the hands when not in combat. A thong was often shown at the wrist to keep the mittens from hanging off the hand.

1200’s: Illustrations of this era commonly show a coif attached to the Hauberk and possessing with a flap (called a ventail) that could be drawn across the mouth and secured by a strap and buckle or laced at the side of the head. Because of the notations of “ventailles’ in the Song of Roland, we know of their existence, though be it uncommon at the end of the 11th century.

1250: Individualized fingers began to be shown on the mufflers in illustrations, but the earlier single-lobe muffler appeared to remain much more popular.

Maciejowski Bible, 1244-1254 Pierpoint Morgan Library of New York; m.638. |

Image of armed warrior from Guardians of the Holy Sepulchre, 1345-1350, Freiburg in Breisgau Cathedral. |

1250-1300: It is very probable that various types of soft armor were used under mail from it’s beginnings; but I have not been able to note definitive evidence. Prior to the second half of the 12th century there was not much written on the topic. During the second half of the 12th century quilted defenses were noted in numerous texts as being worn both under mail as a pourpoint and over it as a Gambeson. The latter has been noted by texts as being used commonly under mail as well. To the contrary of this common sense soft armor concept, The Maciejowski Bible (CIRCA 1250) shows that mail was known to have been worn over only a knee length shirt with a tighter fitting wrist length sleeve.

Maciejowski Bible, 1244-1254 Pierpoint Morgan Library of New York; m.638.

Quilted thigh-defenses also came into common use under chausses no later the second quarter of the 13th century. Towards the centuries end this defense was depicted with increasing frequency as being worn over the chausses. Leather was also known to have been used to reinforce certain areas mail such as the knees during this time.

1270: Wellesburn de Montfort effigy shows a distinct lack of a ventail as does the Effigy of Ugo de Cervellon. (Reference 1066-1082: Paragraph pictures above for mid 14th-century use)

1375-1400: Toward the end of the 14th-century, plates of metal began to become integrated with the suits of mail such as those on the back of the fingered mufflers of an armed warrior depicted in the Guardians of the Holy Sepulchre. It became increasingly popular for warriors to wear leg and/or arm harness’ with mail hauberks until mail was reduce to patchwork protecting only the areas where the coverage of plate armor had not yet mastered such as the underarm.

1400-1500: The beginning of the 15th century marked the beginning of the decline in the popularity of mail and the increased use of white harness.

1501-1875: Mail continued to be used well into the 19th-century as a viable armor though it’s popularity would never reach the height it attained in the 14th century.

Present: Mail is still used today as a protective armor in three main fields. To my knowledge, only one of these fields retains full suits for use. The diving industry produces small diameter mail for use on dives where sharks are expected and / or desired to be encountered. The other two industries that still use mail, (meat processing and cutlery) often use 1/8” diameter mail gloves to protect their workers hands.

General Fabrication:

The suit of mail before you is the conclusion of research from numerous sources and, as usual with this type of study, a tad bit of theory to fill in the blanks.

I began this project winding my own links, but after about 10,000 decided my time was better spent in purchasing them. I found a distributor with links very close to those I formed, and therefore lost no ground on the project.

I chose to construct this suit with butted mail for several reasons. The first and foremost was the lack of a forge and welding equipment at the beginning of this project. This kept me from making the solid ring portions common to the period of my persona. During production both the riveted and solid rings are flattened slightly on their faces. This is not the case with butted rings. I felt using butted ring on the entire suit would be astatically better then intermixing them with riveted units. It was, in my opinion, better to only change one aspect of the suits period appearance then two. Either way I would be using butted rings, which were not the period norm; combining their use with riveted rings would mix ‘flat’ and ‘round’ mail and would have only pushed me further from period construction.

Because I planned to be able to wear this armor in any season and weather, I chose to use stainless steel for my base material and rubber soles on the chausses. In period thick leather would have been used for a footman’s soles or the entire foot would have been encased in mail for a mounted user.

Footmans chausse sole. In Situ church, Tickenham, Somerset, Engkland

My first version of the chausses possessed leather soles and upon testing the comfort level in my yard, I slid on the minor sloped, wet grass terrain. This prompted me to think it much safer to use a sole with more grip and stability, especially since I would be caring an additional 40+ pounds of metal when all was said and done.

The tools I used are as follows:

Winding and cutting:

A hand drill

A steel mandrel

A handsaw

Various files

A Dremel tool and cutting blade