Culture of Malaysia

The Malay are

Malaysia's largest ethnic group, accounting for over half the

population and the

national language. With the oldest

indigenous peoples they form a group called bumiputera, which

translates as "sons" or "princes of the

soil." Almost all Malays are Muslims, though Islam here is

less extreme than in the Middle East. Traditional Malay culture

centers around the kampung, or village, though today one is just

as likely to find Malays in the cities.

national language. With the oldest

indigenous peoples they form a group called bumiputera, which

translates as "sons" or "princes of the

soil." Almost all Malays are Muslims, though Islam here is

less extreme than in the Middle East. Traditional Malay culture

centers around the kampung, or village, though today one is just

as likely to find Malays in the cities.

The Chinese traded

with Malaysia for centuries, then settled in number during the

19th century when word of riches in the Nanyang, or "South

Seas," spread across China. Though perhaps a stereotype, the

Chinese are regarded as Malaysia's businessmen, having succeeded

in many industries. When they first arrived, however, Chinese

often worked the most grueling jobs like tin mining and railway

construction. Most Chinese are Tao Buddhist and retain strong

ties to their ancestral homeland. They form about 35 percent of

the population.

Indians had been

visiting Malaysia for over 2,000 years, but did not settle en

masse until the 19th century. Most came from South India, fleeing

a poor economy. Arriving in Malaysia, many worked as rubber

tappers, while others built the infrastructure or worked as

administrators and small businessmen. Today ten percent of

Malaysia is Indian. Their culture -- with it's exquisite Hindu

temples, cuisine, and colorful garments -- is visible throughout

the land.

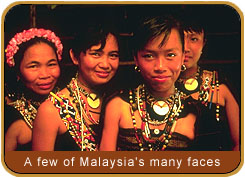

The oldest

inhabitants of Malaysia are its tribal peoples. They account for

about 5 percent of the total population, and represent a majority

in Sarawak and Sabah. Though Malaysia's tribal people prefer to

be categorized by their individual tribes, peninsular Malaysia

blankets them under the term Orang Asli, or "Original

People." In Sarawak, the dominant tribal groups are the

Dayak, who typically live in longhouses and are either Iban (Sea Dayak) or

Bidayuh (land Dayak). In Sabah, most tribes fall under the term

Kadazan. All of Malaysia's tribal people generally share a strong

spiritual tie to the rain forest

Cultures have been meeting and

mixing in Malaysia since the very beginning of its history.More

thanfifteen hundred years ago a Malay kingdom in Bujang Valley

welcomed traders from China and India. With the arrival of gold

and silks, Buddhism and Hinduism also came to Malaysia. A

thousand years later, Arab traders arrived in Malacca and brought

with them the principles and practices of Islam. By the time the

Portuguese arrived in Malaysia, the empire that they encountered

was more cosmopolitan than their own.

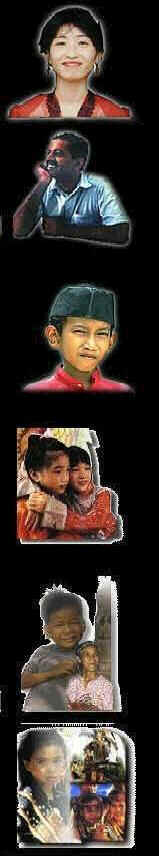

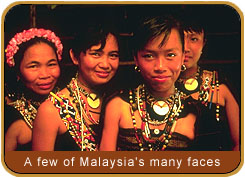

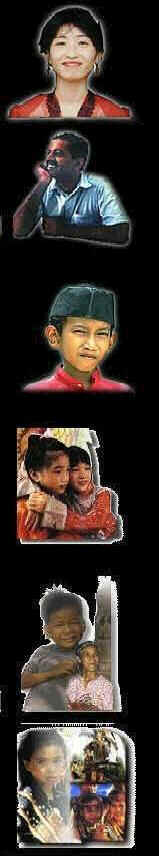

Malaysia's cultural mosaic is marked by many

different cultures, but several in particular have had especially

lasting influence on the country. Chief among these is the

ancient Malay culture, and the cultures of Malaysia's two most

prominent trading partners throughout history--the Chinese, and

the Indians. These three groups are joined by a dizzying array of

indigenous tribes, many of which live in the forests and coastal

areas of Borneo. Although each of these cultures has vigorously

maintained its traditions and community structures, they have

also blended together to create contemporary Malaysia's uniquely

diverse heritage.

One example of the complexity with which

Malaysia's immigrant populations have contributed to the nation's

culture as a whole is the history of Chinese immigrants. The

first Chinese to settle in the straits, primarily in and around

Malacca, gradually adopted elements of Malaysian culture and

intermarried with the Malaysian community. Known as babas and

nonyas, they eventually produced a synthetic set of practices,

beliefs, and arts, combining Malay and Chinese traditions in such

a way as to create a new culture. Later Chinese, coming to

exploit the tin and rubber booms, have preserved their culture

much more meticulously. A city like Penang, for example, can

often give one the impression of being in China rather than in

Malaysia.

Another example of Malaysia's extraordinary

cultural exchange the Malay wedding ceremony, which incorporates

elements of the Hindu traditions of southern India; the bride and

groom dress in gorgeous brocades, sit in state, and feed each

other yellow rice with hands painted with henna. Muslims have

adapted the Chinese custom of giving little red packets of money

(ang pau) at festivals to their own needs; the packets given on

Muslim holidays are green and have Arab writing on them.

You can go from a Malaysian

kampung to a rubber plantation worked by Indians to Penang's

Chinese kongsi and feel you've traveled through three nations.

But in cities like Kuala Lumpur, you'll find everyone in a grand

melange. In one house, a Chinese opera will be playing on the

radio; in another they're preparing for Muslim prayers; in the

next, the daughter of the household readies herself for classical

Indian dance lessons.

Perhaps the easiest way to begin

to understand the highly complex cultural interaction which is

Malaysia is to look at the open door policy maintained during

religious festivals. Although Malaysia's different cultural

traditions are frequently maintained by seemingly self-contained

ethnic communities, all of Malaysia's communities open their

doors to members of other cultures during a religious

festival--to tourists as well as neighbors. Such inclusiveness is

more than just a way to break down cultural barriers and foster

understanding. It is a positive celebration of a tradition of

tolerance that has for millennia formed the basis of Malaysia's

progress.

Back to Top

Music & Dance in Malaysia

Music and dance are almost inseparable in the

Malaysian culture. Where there is one, the other is not far

behind. True to Malaysia's heritage, dances vary widely and are,

if not imports direct from the source nation, heavily influenced

by one or more of Malaysia's cultural components. Much of

Malaysian music and dance has evolved from more basic needs into

the mesmerizing, complex art forms they are today.

Traditional music is centered around the

gamelan, a stringed instrument from Indonesia with an

otherworldly, muffled sound. The lilting, hypnotic beats of

Malaysian drums accompany the song of the gamelan; these are

often the background for court dances. Malaysia's earliest

rhythms were born of necessity. In an age before phone and fax,

the rebana ubi, or giant drums, were used to communicate from

hill to hill across vast distances. Wedding announcements, danger

warnings, and other newsworthy items were drummed out using

different beats. The rebana ubi are now used primarily as

ceremonial instruments. The Giant Drum Festival is held in

Kelantan either in May or June.

Dikir barat is a style of call and response

singing originating in Kelantan (Malm 1974). It is well known

throughout the Peninsular through local television and performing

groups. A dikir barat group, which may be of any size, is led by

a tukang karut who makes up poems and sings them as he goes

along. The chorus echoes in response, verse by verse. Dikir barat

groups usually perform during various festive occassions, and

their poems are usually light entertainment and may be about any

topic, but are not religious in nature. The chorus traditionally

consists of all men, but modern groups, especially those

performing on television, often include women. Traditionally, no

musical instruments are used, the singing being accompanied

instead by rhythmic clapping and energetic body movements. Some

groups however do use a pair of frame drums or rebana, a shallow

gong and a pair of maracas, for accompaniment. (Aziz & Wan

Ramli 1994).

Mak Yong is an

ancient dance-theatre form incorporating the elements of ritual,

stylized dance and acting, vocal and instrumental music, story,

song, formal as well as improvised spoken text.It is performed

principally in the state of Kelantan, Malaysia. Many theories

have been advanced to explain the genre's origins. Its roots

obviously sink deep into animism as well as shamanism.

Briefly early in the present century, an

unsuccessful attempt was made in Kelantan to create a palace

version of mak yong. The mak yong orchestra is made up of a

three-stringed spiked fiddle (rebab), a pair of double-headed

barrel drums(gendang) and a pair of hanging knobbed

gongs(tetawak) while the genre's musical repertoire consists of

approximately thirty pieces, most of them accompanied by singing

and dancing. No stage-properties and few simple hand-properties

are used.

In mak yong, the male lead role (pak

yong) is conventionally played by female performers. In addition

there are the following roles: the female lead (mak yong); a pair

of clowns (peran), a pair of female attendants (inang) as well as

a wide range of lesser roles including those of gods and spirits,

orges or giants, palace functionaries and animals.

The mak yong repertoire consists of a

dozen or so stories, still existing in the oral tradition,

dealing with the adventures of gods or mythical kings. The

principal, and earliest story in the mak yong repertoire,

entitled Dewa Muda, has tremendous spiritual significance. Mak

yong performances last between about 9.00 p.m and midnight, and a

story is generally completed in several nights.

Similarly, silat, an elegant

Malaysian dance form, originated as a deadly martial art. The

weaponless form of self-defense stripped fighting to a bare

minimum. Silat displays are common at weddings and other

festivals; the dancer will perform sparring and beautiful

routines to accompanying drums and other musical instruments.

The candle dance is one of

Malaysia's most breathtakingly beautiful performance arts.

Candles on small plates are held in each hand as the dancer

performs. As the performer's body describes graceful curves and

arcs, the delicate candle flames become hypnotic traces.

The Joget, Malaysia's most popular traditional

dance, is a lively dance with an upbeat tempo. Performed by

couples who combine fast, graceful movements with rollicking good

humor, the Joget has its origins in the Portuguese folk dance,

which was introduced to Malacca during the era of the spice

trade.

Among the many different traditional theatres

of the Malays, which combine dance, drama, and music, no other

dance drama has a more captivating appeal than Mak Yong. This

ancient classic court entertainment combines romantic stories,

operatic singing and humor.

The Datun Julud is a popular dance of Sarawak,

and illustrates the age-old tradition of storytelling in dance.

The Datun Jalud tells of the happiness of a prince when blessed

with a grandson. It was from this divine blessing that the dance

became widespread among the Kenyah tribe of Sarawak. The Sape, a

musical instrument, renders the dance beats, which are often

helped along by singing and clapping of hands.

Although

Malaysia's cultural heritage is rich and varied almost beyond

belief, it would be a mistake to assume that heritage to be

wholly traditional. Malaysia has joined the recent world music

trend by updating many of its beautiful traditional sounds.

Modern synthesizers accompany the gamelan and the drums for a

danceable, hypnotic sound you won't soon forget.

Although

Malaysia's cultural heritage is rich and varied almost beyond

belief, it would be a mistake to assume that heritage to be

wholly traditional. Malaysia has joined the recent world music

trend by updating many of its beautiful traditional sounds.

Modern synthesizers accompany the gamelan and the drums for a

danceable, hypnotic sound you won't soon forget.

Back to Top

Art and Architecture

Malaysian decorative art forms include colorful

batik cloth, silverware, pewter items, and woodcarvings. Like

other elements of Malaysian culture, its architecture reflects

influences from India, China, and Islam. These influences are

most pronounced in religious structures. The British introduced

colonial architecture and, in buildings such as the old post

office and railway station in Kuala Lumpur, the Moorish style.

Music, Dance, and Drama.

Hindu, Islamic, and Indonesian forms influenced

music in Malaysia. For example, wayang kulit (shadow-puppet

theater), was introduced from Java in the 13th century, and today

is most commonly found in the state of Kelantan. Malaysian

musical instruments include distinctive drums (gendang), of which

there are at least 14 types; gongs and other percussion

instruments made from native materials such as bamboo (kertuk and

pertuang) and coconut shells (raurau); and a variety of wind

instruments, including flutes. Ensembles (nobat) and orchestras

(gamelan) play these instruments at special occasions. Chinese

musical forms, including Chinese opera, were more recently

introduced into Malaysia; however, today's young Malaysians of

Chinese descent have little interest in such forms of music.

Back to Top

Theatre

|

Perhaps the best known Malaysian

theater event is the wayang kulit. Before the

encroachment of television, the wayang kulit, or shadow

puppet play, was the favorite after-dark entertainment.

The enang, as the puppeteer was called, directed the

puppets' intricate movements while singing dozens of

parts in a performance which often lasted several hours.

The wayang kulit draws its inspiration from the Ramayana,

the Hindi epic comprised of a potpourri of immortal

tales. The wayang kulit throws in a handful of Javanese

and Malay characters for good measure and then pits good

against evil in a classic plot. Warrior animals, giants,

ghouls, princes, and priests battle it out to the finish

in this rousing epic. |

Back to Top

Games & Pastimes

In a world where nature provided for many of humankind's

needs, leisure was honed to an art form. Much of Malaysian

leisure time is occupied by elaborate competitions. Kite-flying

is a favorite among participants and spectators alike.  Kites, called waus, are painstakingly

designed and crafted in vibrant colors and patterns. Intricate

floral cutouts are pasted on, building up the design until the

kite is ready for the bright paper tassels that complete its

decoration. Kite construction is an ancient art passed down from

the nobles of the Melakan court. Over the dried padi fields, a

wau bulan, or moon kite, catches an upcurrent of air. Its wing

span is larger than that of an albatross. What used to be a

post-harvest diversion among padi farmers has become an

international event. Wau festivals are organized each year and

draw participants from as far away as the Netherlands, Japan,

Germany, Belgium, and Singapore.

Kites, called waus, are painstakingly

designed and crafted in vibrant colors and patterns. Intricate

floral cutouts are pasted on, building up the design until the

kite is ready for the bright paper tassels that complete its

decoration. Kite construction is an ancient art passed down from

the nobles of the Melakan court. Over the dried padi fields, a

wau bulan, or moon kite, catches an upcurrent of air. Its wing

span is larger than that of an albatross. What used to be a

post-harvest diversion among padi farmers has become an

international event. Wau festivals are organized each year and

draw participants from as far away as the Netherlands, Japan,

Germany, Belgium, and Singapore.

The pre-harvest counterpart to the post-harvest wau-flying is

top-spinning, a game requiring great strength, excellent timing,

and dexterity. These are not childrens' toys. A gasing, or

spinning top, can weigh up to ten pounds and can sometimes be as

large as a dinner plate. Gasing competitions are judged by the

length of time each top spins. The tops are set spinning by

unfurling a rope that has been wound about the top. A gasing

expert can set one spinning for over an hour.

Silat is at once a fascinating, weaponless Malay art of self

defense and also a dance form that has existed in the Malay

Archipelago for hundreds of years. Like the best martial arts,

silat is often more about the spirit than the body. The silat

practitioner also develops spiritual strength, according to the

tenets of Islam.

In an age when many of the martial arts are dying out, young

people are especially drawn to this art--there are countless

silat groups in Malaysia, each with their own style. Silat

demonstrations are held during weddings, national celebrations,

and of course during silat competitions.

Sepak Takraw is one of Malaysia's most popular sports. In a

game reminiscent of hackey-sack (or perhaps the source for it),

players use heels, soles, in-steps, thighs, shoulders and

heads--everything but hands--to keep the small rattan ball aloft.

Back to Top

Crafts

Batik

Hindu traders

first brought batik to Malaysia eons ago, and the art of dying

fabric has been an established tradition for centuries. Designs

are first sketched out on cloth, then blocked off with wax

outlines. They are then painted and later sealed with TK.

Kite Making

Kite Making

Kites, called

waus, are painstakingly designed and crafted in vibrant colors

and patterns. Intricate floral cutouts are pasted on, building up

the design until the kite is ready for the bright paper tassels

that complete its decoration. Kite construction is an ancient art

passed down from the nobles of the Melakan court

Pewter Making

Having the world's largest reserves of tin, it

seems appropriate enough that Malaysia also produces what is

widely regarded as the world's finest pewter. Most of it is

produced at the Royal Selangor Pewter Factory, which lies

just outside of Kuala Lumpur. The factory was founded in 1885 by

Yoon Koon, a Chinese artisan who crafted objects only for the

aristocracy. Today Royal Selangor is the largest single

manufacturer of fine pewter in the world, and and it is still run

by Koon's third-generation descendants. The factory gives a full

tour of the production floor, and visitors to the gift shop have

the privilege of buying any of the items duty-free.

Having the world's largest reserves of tin, it

seems appropriate enough that Malaysia also produces what is

widely regarded as the world's finest pewter. Most of it is

produced at the Royal Selangor Pewter Factory, which lies

just outside of Kuala Lumpur. The factory was founded in 1885 by

Yoon Koon, a Chinese artisan who crafted objects only for the

aristocracy. Today Royal Selangor is the largest single

manufacturer of fine pewter in the world, and and it is still run

by Koon's third-generation descendants. The factory gives a full

tour of the production floor, and visitors to the gift shop have

the privilege of buying any of the items duty-free.

Weaving

The jungle provides an abundance of ideal

materials for Malaysia's many types of weaving. The thorny vines

of the rattan tree, for example, are worked and woven into

comfortable chairs and tables -- unique furniture that was so

popular with the English that it could be seen in the parlors of

just about every British resident. The strong and versatile

fronds of the sago palm are also superbly suited for crafting. In

Borneo, the sago is dyed and woven into beautiful and distinctly

patterned jewelry, baskets, hats, floor mats, and more.

The jungle provides an abundance of ideal

materials for Malaysia's many types of weaving. The thorny vines

of the rattan tree, for example, are worked and woven into

comfortable chairs and tables -- unique furniture that was so

popular with the English that it could be seen in the parlors of

just about every British resident. The strong and versatile

fronds of the sago palm are also superbly suited for crafting. In

Borneo, the sago is dyed and woven into beautiful and distinctly

patterned jewelry, baskets, hats, floor mats, and more.

Iban Woman Weaver, Sarawak

A woman weaves using

traditional techniques at Kampong Budaya in Sarawak. The village

has been declared a Cultural Village since 1990 to protect the

skills and customs of the Iban population. Malaysia.

Wood Carving

On both the

peninsula and in Borneo, wood carving reaches an astounding level

of intricacy. What is truly special about this art form in

Malaysia is that all of her cultures have perfected it. You see

it everywhere: in the delightful porticos of Malay houses, in the

roofs and altars Chinese and Hindu temples, on the prows of

colorful fishing boats, and in the burial poles and masks of

Sarawak.

A

kris is can only be made by an empu, a revered

artisan who is also endowed with magical powers.

Once an empu selects a day to begin the task, he fasts and prays,

warding off evil spirits and wining the favors of the demit,

or good genies.

To forge a kris blade, the empu

alternates one layer of steel with two layers of special iron

extracted from a meteorite. This is necessary for the pamor,

or silvery marbling of the blade. The layers are forged together

and flattened. To obtain a particular pamor, the empu twists the

two halves of the steel bar separately. This is repeated as many

times it takes to get the desired effect. The sequence of

layering, bending, beating and forging forms a number of layers.

Generally, a good kris has 64 layers of iron and pamor. It is

said that some have thousands.

The blade is forged into its final

shape, straight or curved, then given ribbing and tang. Using

very fine files, grindstones, and chisels, the ribbing is

heightened, relief created on the blade, and the ricikan

(the characteristic teeth or projections on a kris) is chiseled.

Finally, the emput makes the ganja, or base, and tempers the

blade by bringing it to red hot and immersing it rapidly in

coconut oil.

The entire process can take

months, partly because the empu will only work on days that he

considers favorable. The blade is considered incomplete until it

is merged with the handle and the sheath, and the owner has made

offerings and contacted the spirit of the kris by dream.

Back to Top

Myths & Legends

To the orang asli, the "original people" who have

for millenia inhabited the forests of Malaysia, the earth was an

abode for more than the diversity of plant and animal life. The

world's oldest jungles, dense with mystery, were the playground

of spirits, both benevolent and, well, less so.

Prominent natural features--and there are many in

Malaysia--were wreathed in legend. Tioman Island is said to have

been a dragon princess who decided to make her home where Tioman

now rises out of the sea. Tranquil Lake Chini in the wilds of

Pahang is thought to be the site of a magnificent Khmer city now

sunk beneath the lotus blossoms. Mount Ophir, in Johor, is said

to be the home of 'Puteri Gunung Ledang', a legendary princess

once wooed by the Sultan of Malacca. The princess' beauty is

still associated with the natural charms of the mountain itself.

Langkawi Island has no such creation story, but the curse laid on

the island by a princess falsely accused of adultery is one of

the best-known of Malaysia's magical myths.

The supernatural imbues not only the land and water, but

living things as well. The orang asli believe that one's

semangat--soul or life force--traveled abroad during sleep;

dreams were the record of the soul's adventures. In the city, it

is a little harder to find someone who believes so wholeheartedly

in what was once a compelling way of thought. But fragments of

the old mythological system remain; the kris--the wavy-bladed

Malay dagger--is a shining example. Many Malays have their own

kris as well as their own kris tales. The kris is reputed to be

able to fly by night and seek out victims (their owners' enemies,

presumably) without a guiding hand. One who possessed a loyal

kris was indeed powerful.

"The kris

is reputed to be able to fly by night and seek out victims (their

owners' enemies, presumably) without a guiding hand. One who

possessed a loyal kris was indeed powerful."

"The kris

is reputed to be able to fly by night and seek out victims (their

owners' enemies, presumably) without a guiding hand. One who

possessed a loyal kris was indeed powerful."

The manuscript above relates the story of Hang

Tuah, the most revered warrior of the Malaccan Sultanate. The

Sultan Tun Perak ordered Tuah to be executed after he offended

the sultan, but a loyal bendahara (royal advisor) secretly

imprisoned him instead. Courtiers later discovered Tuah's best

friend, Hang Kasturi, romancing one of the sultan's concubines,

and surrounded the palace - but no one dared go in to capture

Kasturi. When the sultan was told that Tuah was still alive, he

ordered Tuah to kill his best friend to prove his loyalty. During

the fight, Tuah embedded his kris in the palace wall three times,

but Kasturi allowed him to remove it. But when the same thing

happened to Kasturi, Tuah stabbed him in the back."Does a

man who is a man go back on his word like that," asked a

dying Kasturi. "Who need play fair with you, you who have

been guilty of treason," Tuah replied. The sultan rewarded

him with the title laksamana, or admiral.

Back to Top

States

States

Tourism

Tourism

National Symbols

National Symbols

History

History

Geography

Geography

Flora & Fauna

Flora & Fauna

Economy

Economy

Culture

Culture

Festivals

Festivals

Transportation

Transportation

Accommodation

Accommodation

Foreign Exchange

Foreign Exchange

Food

Food

Fruits

Fruits

national language. With the oldest

indigenous peoples they form a group called bumiputera, which

translates as "sons" or "princes of the

soil." Almost all Malays are Muslims, though Islam here is

less extreme than in the Middle East. Traditional Malay culture

centers around the kampung, or village, though today one is just

as likely to find Malays in the cities.

national language. With the oldest

indigenous peoples they form a group called bumiputera, which

translates as "sons" or "princes of the

soil." Almost all Malays are Muslims, though Islam here is

less extreme than in the Middle East. Traditional Malay culture

centers around the kampung, or village, though today one is just

as likely to find Malays in the cities.

Although

Malaysia's cultural heritage is rich and varied almost beyond

belief, it would be a mistake to assume that heritage to be

wholly traditional. Malaysia has joined the recent world music

trend by updating many of its beautiful traditional sounds.

Modern synthesizers accompany the gamelan and the drums for a

danceable, hypnotic sound you won't soon forget.

Although

Malaysia's cultural heritage is rich and varied almost beyond

belief, it would be a mistake to assume that heritage to be

wholly traditional. Malaysia has joined the recent world music

trend by updating many of its beautiful traditional sounds.

Modern synthesizers accompany the gamelan and the drums for a

danceable, hypnotic sound you won't soon forget.

Kites, called waus, are painstakingly

designed and crafted in vibrant colors and patterns. Intricate

floral cutouts are pasted on, building up the design until the

kite is ready for the bright paper tassels that complete its

decoration. Kite construction is an ancient art passed down from

the nobles of the Melakan court. Over the dried padi fields, a

wau bulan, or moon kite, catches an upcurrent of air. Its wing

span is larger than that of an albatross. What used to be a

post-harvest diversion among padi farmers has become an

international event. Wau festivals are organized each year and

draw participants from as far away as the Netherlands, Japan,

Germany, Belgium, and Singapore.

Kites, called waus, are painstakingly

designed and crafted in vibrant colors and patterns. Intricate

floral cutouts are pasted on, building up the design until the

kite is ready for the bright paper tassels that complete its

decoration. Kite construction is an ancient art passed down from

the nobles of the Melakan court. Over the dried padi fields, a

wau bulan, or moon kite, catches an upcurrent of air. Its wing

span is larger than that of an albatross. What used to be a

post-harvest diversion among padi farmers has become an

international event. Wau festivals are organized each year and

draw participants from as far away as the Netherlands, Japan,

Germany, Belgium, and Singapore.

Kite Making

Kite Making Having the world's largest reserves of tin, it

seems appropriate enough that Malaysia also produces what is

widely regarded as the world's finest pewter. Most of it is

produced at the Royal Selangor Pewter Factory, which lies

just outside of Kuala Lumpur. The factory was founded in 1885 by

Yoon Koon, a Chinese artisan who crafted objects only for the

aristocracy. Today Royal Selangor is the largest single

manufacturer of fine pewter in the world, and and it is still run

by Koon's third-generation descendants. The factory gives a full

tour of the production floor, and visitors to the gift shop have

the privilege of buying any of the items duty-free.

Having the world's largest reserves of tin, it

seems appropriate enough that Malaysia also produces what is

widely regarded as the world's finest pewter. Most of it is

produced at the Royal Selangor Pewter Factory, which lies

just outside of Kuala Lumpur. The factory was founded in 1885 by

Yoon Koon, a Chinese artisan who crafted objects only for the

aristocracy. Today Royal Selangor is the largest single

manufacturer of fine pewter in the world, and and it is still run

by Koon's third-generation descendants. The factory gives a full

tour of the production floor, and visitors to the gift shop have

the privilege of buying any of the items duty-free.

The jungle provides an abundance of ideal

materials for Malaysia's many types of weaving. The thorny vines

of the rattan tree, for example, are worked and woven into

comfortable chairs and tables -- unique furniture that was so

popular with the English that it could be seen in the parlors of

just about every British resident. The strong and versatile

fronds of the sago palm are also superbly suited for crafting. In

Borneo, the sago is dyed and woven into beautiful and distinctly

patterned jewelry, baskets, hats, floor mats, and more.

The jungle provides an abundance of ideal

materials for Malaysia's many types of weaving. The thorny vines

of the rattan tree, for example, are worked and woven into

comfortable chairs and tables -- unique furniture that was so

popular with the English that it could be seen in the parlors of

just about every British resident. The strong and versatile

fronds of the sago palm are also superbly suited for crafting. In

Borneo, the sago is dyed and woven into beautiful and distinctly

patterned jewelry, baskets, hats, floor mats, and more.

"The kris

is reputed to be able to fly by night and seek out victims (their

owners' enemies, presumably) without a guiding hand. One who

possessed a loyal kris was indeed powerful."

"The kris

is reputed to be able to fly by night and seek out victims (their

owners' enemies, presumably) without a guiding hand. One who

possessed a loyal kris was indeed powerful."