One of the dilemmas of this century is the hostility toward the piano, an instrument which has spread (like tobacco) with such irresistable force that it is found at the feet of the Cordillères, on the banks of the Ural, on the savanahs and steppes, anywhere there are Europeans (and particularly female ones), so that the traveller will be either repulsed or attracted by its sound when approaching his lodging.

The piano deserves most of this overwhelming criticism. Its temperament is out of tune. It discourages moving and encourages bad playing, which resounds from dawn till well into the night in most cities (especially coastal ones). Restaurants all have them inside, and I'm sure there isn't a minute in Paris where at least one isn't vibrating, after the last girl finishes banging the hammers merrily at the Café Anglais the little future conservatory student rises to start his scales.

But it doesn't puff out cheeks like the horn or flute, or stretch lips like the clarinet, stoop shoulders like the violin or bow legs like the contrabass. It is nearly immobile but one can be found anywhere, to a woman it is a kind of household certificate of a proper education. It is most certainly out of tune, but this defect is so frequently addressed by skilled tuners that their convention of temperament is more acceptable than a poorly intoned violin. In contrast with all other instruments that need the hand of an eminent artist, the piano tolerates mediocrity. With as many as ten notes sounding at the same time it can render both the melody and harmony, and this (we think) is the source of its success. And then marvellous pianists like Liszt, Kalkbrenner and Chopin have made it sacred, able to produce the most beautiful effects of orchestration. The great composers like Meyerbeen, Rossini and Verdi confided it with the first inspirations of their masterpieces. It accompanied Rubini, Lablache and Alboni as they tried their vocal effects. It is, after all the friend and companion to women who prefer reading a favorite score to more superficial pleasures. In 1855 the tremendous efforts spent producing even the worst piano (and so many of these) amounts to an estimated annual value of 75 million francs - 27 million in England, 16 million in Germany, 10 million in France, undiminished despite wars and political and commercial unrest. The house of Pleyel et Cie. account for about one fifth of the French production, but before entering their workshops and grounds and their interesting and complicated work, we should describe (as clearly and quickly as possible) what makes the assembly of wood, metal, ivory and leather into the universal instrument of our age.

The piano is a string instrument that is made to sound by percussion. It has a number of strings corresponding to its compass, and their dimensions, tension and weight all follow a specific pattern. It is well known that with the same density and tension if two parts of a string are proportioned 1 to 1 they sound a unison, in other words they vibrate identically. If they are arranged 2 to 1 they make an octave, 4 to 5 a fifth, 4 to 3 a fourth, 5 to 4 a major third, 6 to 5 a minor third, and 24 to 25 a minor third[!!]. It was Pythagorus (according to Boethius) who determined these proportions geometrically on a monochord.

Changing the tension, thickness and density of the strings by means of precise formulas can also produce these effects, and this science is the basis of the art of the piano builder who must combine with it a knowledge of the resonance and strength of diffent kinds of wood, (unlike on the harp, the strings are fixed on an assembly that affects the intensity and quality of the sound)

No single product of human labor and intelligence has fostered as many inventions, refinements and perfections as the piano, and today's highly evolved (and theoretically perfect) instrument endures similar experiments, which usually aren't organized, original or successful.

We won't try and reproduce the two hundred pages from the Encyclopedia, or even a historical outline of progress up to 1765, concerning the monochord, clavichord, wooden harmonica, and keyed harp, and all the variations of the spinet (spinet with feathered jacks, bowed spinet, spinet with hard wood hammer, spinet with crescendo, vertical spinet), then the harpsichord (clavecin à l'âme, broken harpsichord, vertical harpsichord, clavecytherum, buff harpsichord), and finally the forte-piano or hammered harpsichord. . .

The forte-piano has a pleasant sound and it is suited for music with pathetic harmony arranged by skilled musician, but has been criticized by many masters (such as Mr. Trouflant, organist from Nevers) for being tiresome and painful (in time harmful) to play because of the weight of its hammers. At the same time most of the masters preferred composing for this instrument over the harpsichord due its new effects.

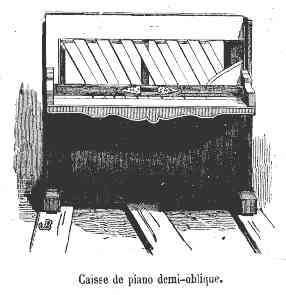

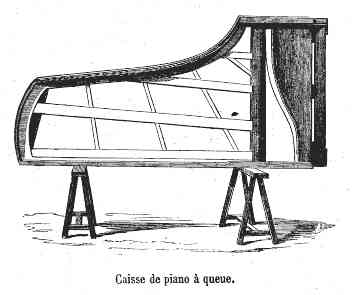

There's not much history about the piano till Godfrey Silbermann started his workshop in 1745 (often the invention is credited to Schroeder in 1717), but thanks to Hein in Augsbourg and Zumpe in London, who sent their expensive little instruments to Paris, the piano gained little by little on the harpsichord. In 1777 Sebastien Erard made France's first piano which was a little oblong parallelogram with five octaves and two strings per note; in 1790 with his brother Philippe he added the third string and improved their sound, and then in 1796 made the first pianos in the same shape as harpsichords, called grand pianos, which have remained the preferred concert piano despite their size.

In 1807 Ignace Pleyel founded the establishment that would become one of the most important houses in the world, beginning in 1824, through his son Camille Pleyel's management. Though he experimented more broadly, Camille Pleyel chose to use the single action and concentrated on improving each of the different components of the instruments, and above all to (jealously) perfecting manufacturing processes which till then were neglected in France to the advantage of products exported by English and German makers. The well-informed reporter at the 1856 Exposition (who is hardly suspected of being partial to this establishement) summed up this export and its causes.

"It is proper to say (writes Mr. Fétis) that on the the greatest improvements in the modern manufacture of pianos rests squarely with the solidity of their tuning, a distingishing feature of good construction. The instruments built by the great houses in Paris and London are often transported considerable distances by every mode of conveyance without ever changing tune. In this regard, the great Parisian house Pleyel et Cie. is particularly distinguished. Their instruments are exported to the most distant countries and the least accessible interiors of the two Americas and Australia, passing many months and turning in every direction, yet finally when they are unpacked the tuning is the same as the moment of departure, a precious quality in countries without tuners."

The different parts of a piano employ so many dissimilar materials (wood, iron, brass, silver, ivory, leather, felt, cloth) that there are many specialized industries that produce each one of the components. Messrs. Rohdem, Schwand, Barbier and many others prepare the actions, plates, and all of their accessories. Most makers purchase these to assemble in order to make instruments that can be sold for a low price. All of the economical pianos (especially those intended to let) are made in this manner, but this excellent division of labor hardly affords perfection to these products. Even when the pieces fit together, after a little playing all that carelessly selected wood starts to give rather awful results.

Workshops like Pleyel and Wolff's make everything under a general direction, and only this way acheive a kind of relatively affordable perfection. Because the case is so important to the sound and solidity of the instrument Mr. Wolff (though enormous sacrifices of time and money) has been able to amass stock valued more than eight hundred thousand francs, cut up, sorted and prepared for the successive production of 900 pianos a year.

Some numbers will give a general idea of the importance of these stores. The warehouses and drying rooms kept in admirable (and necessary) order include 23,500 wrest and hitch planks. These pieces of beech which have to stand the tension of the strings are difficult to dry because of their thickness.

About 300,000 different pieces of oak;

90,00 of beech;

60,000 of pine;

25,000 of basswood;

60,000 of mahogany;

130,000 of rosewood;

Other wood like pear, hornbeam, cedar and false cedar, in the same proportion.

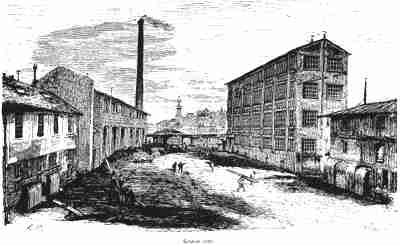

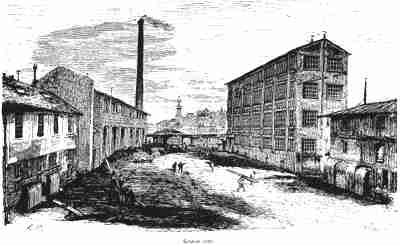

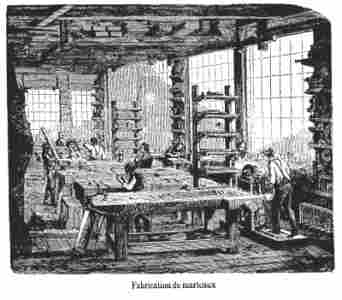

All this wood is prepared and kept in huge workshops (more than four acres) on the east side of rue Marcadet next to rue Rochechouart. Most of it is bought in whole logs from the same places. During the first stage of drying it stays in the open in its bark, then it is cut up (following the grain) into blocks and large boards and stacked out in the open again. The expensive foreign wood meant for veneers is covered over with thatch protecting it from disastrous checking, but all these stacks (shown in the drawing on p.284) are left for months or years to swell and shrink with changing humidity until these cycles are reckoned finished. Properly seasoned wood is examined carefully, rejected for the smallest defect but otherwise delivered to a series of ingenious circular saws used to cut the wood to specific dimensions. The sorted and labelled wood is then shut up into huge kilns until it is ready to be used.

Oak is used making the sides, cheeks, bottom boards, top and bottom panels, toe blocks, doublings of the lower half of the piano, essentially making up the frame of the instrument. Top grade oak has many fine qualities - it is strong, elastic, good grain, flexible and soft. The offcuts are used making veneers for parts (except the planks) that need crossbanding, and it's also used for the large tails and bentsides in grand piano, formed with many layers so they come together in the screw presses that give their shapes on the bucks.

Pine is used resisting the tension of the strings, as well as making footings for the iron frame and different kinds of layers the workers like to call répaissements. A special pine from Switzerland (called picea, from Vorarlberg or Muotte thal) is used making the sounding boards (its great elasticity is described in an earlier article).

Beech is used to make the planks mounted at both ends of the posts in an upright. The top one receives the wrest pins and the lower one carries an iron plate meant to hold the strings with the hitch pins. This wood is stronger than oak and holds the pins fast but it is less stable and hard to keep in exact measure.

Basswood is used making the keyboard. It has very little grain which helps sawing out the curves required by the shapes of the finger keys. Pieces with a lot of runout are used making the cores of certain case parts (like the consoles) that are veneered with island woods.

Hornbeam is very strong and is used for the hammer shanks, bridge caps, blocks, nuts, and all the parts that have to resist the crushing pressure of the strings. The narrow bridge roots must be made of very hard wood because they will be drilled with between 320 and 380 holes for the pairs of bridge pins. They are generally made in beech, but can be made from walnut or maple.

Pear isn't as hard as hornbeam, but it is more pliable and takes a nice polish. It can be used (as can santo domingo mahogany) making action parts such as the flanges (whose centers are lined with cashmere), jacks, levers, and hammer butts (padded against the action of the jack, on what is called its nose). Once the top grade pear is selected the rest is cut up into convenient thicknesses and dyed making the

Woods like maple, service, walnut, and ash can be used for other little pieces of secondary importance, though maple is used for the hammer heads.

Rosewood is meant for veneer but it's also used for the fittings of the cases. Wolff's veneers measure 13 sheets per inch and is very expensive to resaw because most of it is wasted as sawdust. Rosewood is also used for some decorative parts in the action like damper heads and key blocks.

Mahogany is used for similar purposes as rosewood. The most attractively figured mahogany reserved for veneers can be sold for between 5 and 20 francs per sheet, but some mahogany also is suitable for making many of the mounting rails in actions (besides the little parts).

Cedar and false cedar are mostly used for the rails and rods in actions which need to have straight and regular grain. The makers also believe that its scent repels insects attracted by woolens (though not as effectively as the movement in a regularly played instrument).

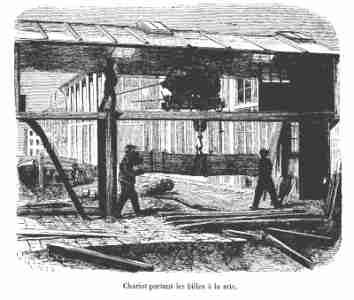

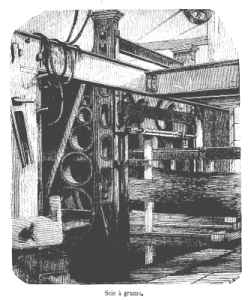

Two machines deserve special mention out of the ingenious and nicely arranged tools used to cut and shape this wood to give form to the instruments (we won't describe the rest in detail), all powered by a 60 horsepower engine. The vertical planers (quite similar to the facing lathe shown at Derosne and Cail) carries the planks being planed on a cast faceplate turning at some speed, while the cutting tool is passed across them with a screw feed. This would be a perfect tool if it weren't so dangerous: from time to time one of the planks is thrown from the chuck to strike menacingly against the wall (we strongly urge Mr. Wolff to seek some clever arrangement to stop the course of these projectiles). The excellent bandsaw is used cutting the attractive ornaments decorating the instrument in wood and brass. It can't cut inside, though, apparently fretwork is made with a drill reciprocating in a cast table.

The little wood pieces used in the interior mechanism of the piano (like the hammer shanks, jacks, and flanges) are turned and fashioned on the top floor, above the sawing shop. One device that could be adapted to different jobs rounds off and planes rods that then are cut to length with small circular saws.

Farther on are the brass workshops where one main product is the comb, a heavy brass bar which is furnished with regular notches by a clever machine. Two of these will be fixed facing opposite on either side of a heavy wood bar used for the hammer rail of an upright. They also make agraffes and blocks (strings pass through one and over the other for termination), the hitch pins, and a lot of other small pieces, initially made of this non-rusting material for more decorative purposes.

The length of the first floor workshops is filled with the oak planks that have been bent into the curves meant for the bentsides in grand pianos.

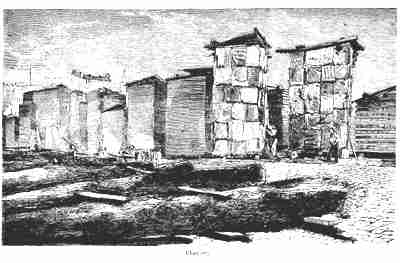

The ironworking shops at the other side of rue Rochechouart make the iron hitch pin plates (called knees for uprights and giraffes for grands), the framing bars, as well as all the other metal pieces used to attach or separate the different wooden pieces of the case and the action. These premises are purposefully situated some distance away from assembly and regulating shops.

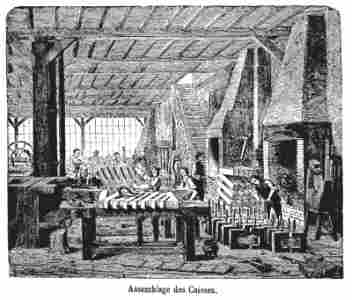

The assembly workers at rue Marcadet have all the pieces they need at hand to complete the case (like a mosaic, or like setting type). They start by installing the sounding board and the two bridges that connect the strings with the resonant panel, which is kept perfectly flat by narrow wood reinforcing beams. The grand soundboard made to fill the entire case, but in the upright it joins part way with a non-sounding plank called the corner.

At the same time the planks are drilled (by means of a bow drill and special center bits) for the hitch pins, bridge pins, blocks, agraffes, and wrest pins (that will serve to fasten, bend, terminate and wind up the strings). In pianinos the blocks are replaced with a single piece pinned nut, and in the bass the grands use a block (a notched brass bar pressed against the top of the strings). The thick plate of bent iron (giraffe) holds the hitch pins and connects the whole instrument. Strong iron bars sustain and reinforce the wooden posts that separate the two planks.

The soundboard is finished and all of the pieces prepared for the strings are solidly attached, the piano is veneered and completely assembled (though not yet varnished) and delivered to the workshops at rue Rochechouart where it will receive the action and strings.

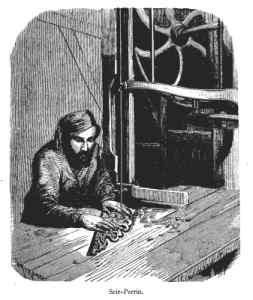

The plain treble strings are made with English or German wire (France doesn't produce iron wire consistently enough to compete with Webster in Birmingham and Muller in Vienna). French brass wire (from nr. 5 to nr. 40) is used wrapping the bass strings to increase their density compensating for a reduction in length in the equation governing their sounding pitches. Their diameter is calculated so the tension is even across the whole instrument with no changes between the first plain string and the last wound string. Mr. Wolff has been experimenting using lighter aluminum wire to lengthen and improve the sound in some of the wound strings in the tenor. The string winding workshop at rue Rochechouart contains many string lathes (based on their perfect products) that defy all comparison.

The stringers (protected with heavy gloves) install the strings and then adjust them by turning the wrest pins (held in the plank by a kind of shallow screw thread).

The action is assembled in workshops at rue Rochechouart. The keyboard is covered in ivory and fixed on the key frame, the keys balanced perfectly on their centers. The action is carefully glued and covered (with leather, cloth, flannel, woolens); the knuckles, backchecks, damper levers are specially padded and carefully covered with buckskin, the hammer heads covered with five layers of calf skin. The jacks are rubbed with plumbago to prevent friction against the knuckles, and the assembled parts are regulated to give the best results (we won't describe their complex but rational mechanisms). Pleyel (like Broadwood in London) prefers the simple action that places the hammer and strings under more direct control than the more active double escapement.

The strung piano is delivered to finishers who install the completed keyboard and action, regulate all the parts to give the best results and deliver the finished instrument to artists who carefully examine each part. The legs are then fitted and the instrument varnished, decorated with its medals and fittings and delivered to its owner (almost always ordered in advance).

Mr. Wolff (working endlessly) isn't content perfecting his friend Pleyel's pianos but has also created a pedalier, appreciatively described by Mr. Niedermeyer :

"The small number of skilled organists has to do with the difficulties of convenient practice. Organs are rare outside of churches, and the rules of ritual aren't conducive to study. In most cases the organist must work on a piano, though in fact only the keyboard itself is the barest point of similarity between the two instruments. Posture, fingering and music all differ, and the wonderful resource in the pedal of the organ is missing entirely from the piano. The techniques and phrasing peculiar to the magnificent 32' ranks controlled by the pedals alone (that produce the lowest musical sounds) can only be mastered through long work (even rapid passages must be slurred).

"Well before the invention of the piano attempts were made adapting pedals to the harpsichord, and the same kind of coupler reapplied to the piano where some of the hammers and strings were set in motion by feet instead of the left hand, adding little to the power of the instrument.

"Mr. Auguste Wolff, a distinguished musician and head of Pleyel, Wolff et Cie., has created a completely independent pedalier arranged with its own strings and hammers as well as its own particular action. It is small enough to use in the most modest apartment. It has the form of a cupboard that is set against a wall, with an adjustable bench is fixed across the front and before this will be placed any sort of piano.

"The performer sits on an adjustable bench above the pedals in front of any kind of piano (upright, square, grand) and the case sets against a wall. The height of this cabinet allows unusually long and thick strings, and very large sounding board for an instrument with only two and a half octaves and the result is a uniquely beautiful and powerful sound, the lowest c is as pure and full as the finest 16' flute pipes (even in the best grand pianos the last octave, especially the last fifth sounds disagreeable and indistinct).

"Following the manner organs add an 8' to a 16' rank, Mr. Auguste Wolff tempers the gravity of the low strings with shorter, finer ones an octave higher combined and sustaining with remarkable fullness.

"This attractive instrument is also affordable, and seems to us to be destined for great favor and complement every grand piano. The organist now can study the most complicated organ works without leaving home, the pianist can learn the numerous masterpieces with pedal parts, and composers can explore new resources for the piano.

"Mr. Wolff modestly denies his pedalier is such an instrument but simply is a means for serious musical study."

translated by Clark Panaccione

Images from Conservatoire national des arts et métiers,

Conservatoire numérique http://cnum.cnam.fr