It is a curious fact that, on any improvement being made on any old article, the improved article, the improved object has always a leaning towards its old shape ; for instances, when railways were first instituted the carriages were in the shape of the old mail coaches, either singly or several coach-bodies joined : and the present generation has seen that motor-cars were in the first case modelled on the old horse-drawn vehicle until a fresh type evolved itself.

This conservatism happened with the piano ; in a very early instrument (1792) the maker, evidently having no faith in the lasting popularity of the pianoforte, combined it with a spinet, so that they might be played simultaneously ; or in case one of the instruments fell into disfavour the other would be removed and played separately.

This conception of the piano cum spinet was not new even then, the ingenious Joseph Merlin, in 1774, and Robert Stodart, in 1777, having evolved the same idea, but their instruments were not made to separate.

It may be mentioned here that the chief difference between the spinet or harpsichord and the piano consists in the strings of the former being put into vibration by the rubbing of a quill attached to a lever (called a jack), whilst in the piano the strings are struck by a hammer. The spinet differs from the harpsichord in having only one string to a note.

This combination of the piano with other musical instruments has always been a mania of inventors, a fine example being an invention of Mr. Cheese, whose "Grand Harmonica" of 1786 was a grand piano with an accompaniment of the musical glasses. The glasses were in the shape of saucer-shaped discs strung on a rod and, being obligingly rotated by a gentleman friend, the lady performer by striking the keys brought into contact with them a little pad of cork moistened with acidulated water, which, pressing against the glass, brought forth those distressing sounds of which that material is capable ; strings corresponding in note to the discs were struck at the same time.

Many other combinations have been made, such as piano and organ, piano and flute, piano and harp, and, more lately, the exceedingly popular piano and harmonium.

Other flights of inventors' fancy were in the direction of substituting for the strings of the pianoforte other forms or substances ; an early example has springs ; another, tuning forks ; another, metal hooks ; again, glass bars. Two of this class, which show how ideas persist, were Mr. John Day's instrument of 1816 with glass bells, and Mr. Newton's, of 1860, with metal gongs, which are practically the same with the exception of the material of which the bells are composed.

The philosopher's stone sought for in musical instruments has been the working of the piano on the principal of the violin, needless to say, an unrewarded task. The strings were to be vibrated by a bow-like device, to give the tone of a violin with greatly increased forte and piano ; but the desired effect has not yet been obtained. The only instrument on that plan, up to the present, which has been at all practicable is the hurdy gurdy, and it is doubtful if the critics quite approve of that. A quaint notion is that of Mr. Southwell (1811), who makes an upright piano, the strings and front of which slope backwards. The inventor says the advantages to the performer must be evident, the front of the instrument being so much away from the face, and the desk at all times ready to receive the music.

A very beautifully shaped model was constructed in 1841 by John Steward, in which he combined the shape of the great harp with the piano ; this he called the "Euphonicon."

The great exhibition of 1851, held in Hyde Park, was the scene of a great display of pianos of all nationalities and descriptions, and it was only natural that such an opportunity of displaying their acheivements should not be passed over by the novely mongers.

Accordingly, we find a twin piano, which had two keyboards - so as to utilise the back of the instrument - for two, four, or six persons. "It forms a handsome ornament for the centre of a room, but can be placed against the side as a single instrument."

A useful piece of furniture was the Tavola piano, whhich formed, when closed, "an elegant drawing room tabke and closet for music." It was in the shape of a square grand, but of only half the depth.

As economy of space seemed to be a desideratum, numerous inventors essayed their hands, and we find Mr. Pape reducing his piano to the size of a Loo table. Going further still in this direction, Messrs. Kirkman produced a miniature grand only 48 inches long by 36 inches wide, with a fill compass of 6 3/4 octaves. This was the smallest instrument (at the time) ever made to be played upon, and was of full and clear tone.

As economy of space seemed to be a desideratum, numerous inventors essayed their hands, and we find Mr. Pape reducing his piano to the size of a Loo table. Going further still in this direction, Messrs. Kirkman produced a miniature grand only 48 inches long by 36 inches wide, with a fill compass of 6 3/4 octaves. This was the smallest instrument (at the time) ever made to be played upon, and was of full and clear tone.

Still keeping on this tack (a proper expression here, as the next example is designed for a yacht), Messrs. Jenkins exhibited their grandly names "patent expanding and collapsing pianofortes," which designation would lead one to think they were made like a Japanese lantern, but no such thing ; it was simply that the keyboard was made to fold flat against the front when not in use, for convenience in transport, or economy in space.

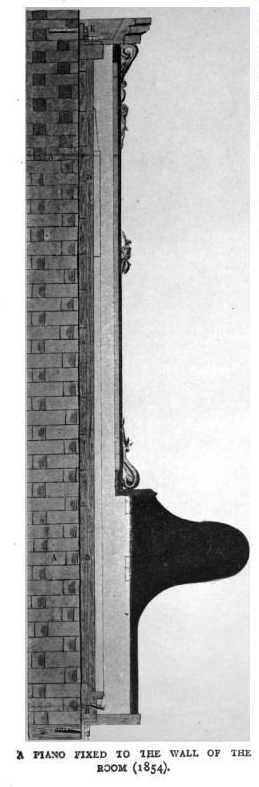

Taking our leave of the palace of glass, we remain for some years without any extraordinary production, the inventors being, doubtless, exhausted by their efforts of 1851, or "falling back for a spring," as Mr. Micawber puts it ; any way, the records are blank until we find, in 1854, Mr. Daniel Hewitt, of Richmond, in Surrey (a professor of music too), taking out a patent to do away with the costly braced framework, and thereby much reduce the cost. This he accomplished by using one of the walls of the room in which the piano was required, affixing to it at proper distances by strong iron bolts, the wreat plank and bent side (the two parts which carry the strings), and interposing the sounding board, there was his piano ready to have the front and keyboard placed in position as shown in the illustration. But what about the expense of preparing the wall if it were jerry-built (not unknown in Mr. Hewitt's days)? Remember, too, the enormous tension of the strings ; while last, but not least, what was to be done when the owner moved to a new residence?

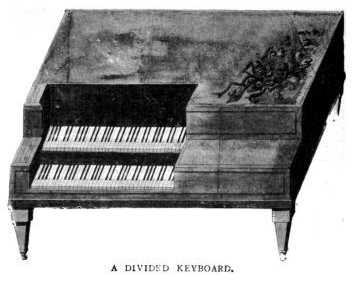

An idea of Mr. Hallett, in 1857, seems not so impracticable. He shows a grand piano with a circular sounding board, over which radiate two, three, or four sets of strings, so that the instrument might have two or more keyboards available for quartettes, etc. The illustration shows only two keyboards.

Turning now to what may be termed the furniture piano, we find a variety of the grand which was mounted on trunnions like a cannon, and when not required might be turned up on end, in the manner of the familiar folding bed ; the bottom might be decorated of covered with a mirror.

How the public scoffed at the mixture piano may be seen in the old satire of 1837, - "The Musical Dresser." Even to-day these freaks are being brought out ; inventors are determined to make use of what they consider wasted space in a piano , and perversely insist on fitting them up to hold music. One man even goes so far as to make a double piano, and use the duplicate half as a music cabinet, another has provided shelves and cupboards, and we notice in his illustration bottles and glasses standing on the shelves ; the effect can be better imagined than described, when one remembers what a discord even one jangling candle sconce can make.

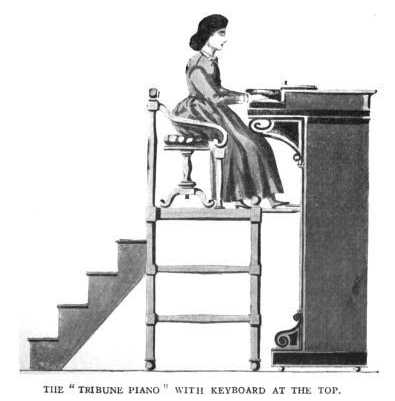

When the upright grand first came into being with its economy of floor space, much dismay was felt when it was found that performers would have to sit with their backs to the audience, or else sideways, and so the great minds at once set themselves to work to overcome whis drawback. The height of these instruments was six feet and over.

One of the more practical of these improvements was that of Mr. Auguste Herce who placed his keyboard at the top of the six-footer, and raised the performer on a platform behind it - as shown in the illustration page 339 ; this he called the "Tribune piano."

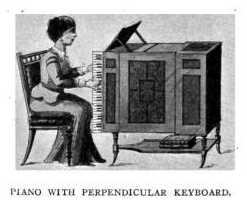

Another invention, and a regular freak this time, was the perpendicular piano, in which, as is seen in the drawing, the keyboards, etc., were placed perpendicularly and played sideways, half the keys on either side - treble on the right hand adn bass on the left. The maker claims for it that it is very small and light, and can be played in a most natural and convenient manner, and the performer can sing to its accompaniment facing the audience.

An ingenious idea to cause a swell and fall in tone is that in which the back of the instrumetn is made to open or close according to the volume of sound required. An earlier variation of this type was to have louvres in front of the piano, opened or closed by means of a pedal.

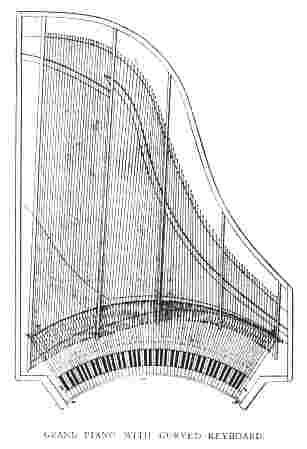

To conclude, a drawing is given of a grand piano with a curved keyboard, which seems to evince possibilities, but evidently has not yet caught on. This was to obviate fatigue to the player by bringing the extreme keys within easier reach.

It may be asked - where do all the old pianos go? The answer was once wittily given : They go to - pieces. And that has doubtless been the fate of most of these "freaks."