PIANOS

AND THEIR MAKERS

THE first attempt to write a history of the pianoforte was made in 1830 by M. Fetis, "Sketch of the History of the Pianoforte and the Pianists," a laborious effort by a brilliant writer, but of little value to the piano maker.

Kusting's "Pratisches Handbuch der Pianoforte Baukunst," Berne, 1844 , is a more practical treatise than Fetis' attempt, but antiquated and only of interest to the historian. The same may be said of the interesting work of Frofessor Firschhof, "Versuch einter Geschichte des Clavierbaues," Vienna, 1853.

Welcker von Gonterschausen published in 1860 "Der Clavierbau in seiner Theorie, Technik und Geschichte," a fourth edition of which was printed in 1870 by Christan Winter, Frankfurt, a./M.

As a practical piano maker, fairly well posted on the laws of acoustics and thoroughly aquainted with the characteristics of all known musical instruments, Welcker has given a work of interest and value. It is to be regretted that his extreme patriotism and rather biased opinion do not permit him to do full justice to pianos made in other countries than Germany. Aside from this fault, his book is to be recommended to the studious piano maker as well as the student of musical-instrument lore.

Dr. Ed. F. Rimbault published in 1860, in London, his ambitous work, "The Pianoforte." Written at the time when the English piano industry was at its height, it is pardonable that the author laid his emphasis on English efforts and achievements rather at the expense of the French, German and Austrian schools. It must be assumed that the achievemetns of the latter were not known to him in their entirety and importance. Especial credit is, however, due to Rimbault for having produced documentary evidence of Christofori's priority as inventor of the pianoforte.

G. F. Sievers of Naples, an able piano maker, published in 1868 his "Il Pianoforte Guida Pratica," with a special atlas showing piano actions in natural size and therefore of great value to the piano student.

Dr. Oscar Paul, a professor at the Conservatory of Music in Leipsic, wrote in 1868, "Geschichte des Claviers." The learned professor of music failed to do justice to the title of his book. Entirely unacquainted with the practical art of piano making, he assumes an authority which is amusing to the knowing reader. Like Welckers, Dr. Paul suffers too much from German egotism. All through the book the effort of ascribing all progress in piano construction to his countrymen is painfully palpable, he even going so far as to imply that Christofori had copied Schröder's invention, an effort which demonstrates Paul's ignorance of action construction. However, the book contains sufficient good matter to repay reading it. Published by A. H. Payen, Leipsic.

For the practical piano maker who reades German, the "Lehrbuch des Pianofortebaues," by Julius Blüthner and Heinrich Gretschel, published in 1872 and revised by Robert Hannemann in 1909, Leipsic, Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, offers much valuable information, treating with great care the construction of the piano and the materials, tools and machinery used in the manufacturing of the instrument. It also has a short essay on acoustics written by Dr. Walter Niemann, who furthermore contributes a history of the piano up to the time of the general introduction of the iron frame.

Edgar Brinsmead's "History of the Pianoforte," London, 1889, dwells too much upon the achievements of the firm of Brinsmead & Sons and loses all importance when compared to A. J. Hipkins' "Description and History of the Pianoforte," published by Novello & Company, London, 1896. An earnest scholar and careful writer, Hipkins successfully avoids the many pitfalls of the lexicographers and gives a clear and succinct description of the development of the piano from its earliest stages to the modern concert grand. The book is well worth careful perusal by anyone interested in the piano industry.

Daniel Spillane's "History of the American Pianoforte," New York, 1890, is an interesting compendium showing the development of the piano industry in the new world, with sidelights upon the men who have been most prominent in that sphere.

Edward Quincy Norton, a piano maker of long and manifold experience, wrote his "Construction and Care of the Pianoforte" in 1892. This book, published by Oliver Ditson & Company of Boston, contains valuable suggestions for tuner and repairer, and is still meeting with a ready sale.

The more modern books, "Piano Saving and How to Accomplish It," by Edwayrd Lyman Bill, and "The Piano, or Tuner's Guide," by Spillane, also William B. White's books, "Theory and Practice of Pianoforte Building," "A Technical Treatise on Piano Player Mechanism," "Regulation and Repair of Piano and Player Mechanism, Together with Tuning as Scienvce and Art" and "The Player Pianist," all published by Edward Lyman Bill, New York, have found wide circulation among practial piano makers because of their popular treatment of intricate subjects. All of these books are almost indispensable for a conscientious tuner and repairer.

Among the strictly scientific works, John Tyndall's treatise on "Sound" and Helmholtz' "Sensations of Tone" offer much food for thought to the student of acoustics, although Helmholtz's originally much lauded "Tone Wave Theory," as well as his so-called discovery of the "Ear Harp," have been vigourously attacked by Henry A Mott in his book, "The Fallacy of the Present Theory of SOund" (New York, John Wiley & Sons), and by Siegried Hansing in "Das Pianoforte in seinen akustischen Anlagen," New York, 1888, revised edition, Schwerin i./M., 1909.

Hansing's work is beyond question the most important, so far written, on the construction of the pianoforte.  His studies in the realm of acoustics disclose a most penetrating mind capable of exact logical reasoning. He bases his conclusions on exaustive studies, without regard to the accepted theories of earlier scientists. As a thoroughly practical piano maker and master of his art, Hansing studied cause and effect in its application to the piano, and his book is a rich mine of information for the prospective piano designer and constructor. Free from any business affiliations, he treats his subject with an imparioan and unbiased keenness of perception which is at once impressive and convincing.

His studies in the realm of acoustics disclose a most penetrating mind capable of exact logical reasoning. He bases his conclusions on exaustive studies, without regard to the accepted theories of earlier scientists. As a thoroughly practical piano maker and master of his art, Hansing studied cause and effect in its application to the piano, and his book is a rich mine of information for the prospective piano designer and constructor. Free from any business affiliations, he treats his subject with an imparioan and unbiased keenness of perception which is at once impressive and convincing.

Dr. Walter Niemann's "Das Klavierbuch," C. F. Kahnt Nachfolger, Leipsic, is an entertaining little book on the piano, its music, composers and virtuosos, containing many illustrations of rare and valuable pictures of noted artists playing the piano.

Henry Edart Krehbiel's more pretentious and serious work, "The Pianoforte and Its Music," Scribner, New York, 1911, is a valuable work of interest to the student of the piano, the musician and music lover.

Of special interest to the studious piano maker are the catalogues of old instruments collected by Morris Steinert of New Haven and Paul de Wit of Leipsic. "M. Steinert's Collection of Keyed and Stringed Instruments" is the title of a book published by Charles F. Tretbar, Steinway Hall, New York. It contains excellent illustration of the clavichords, spinets, harpsichords and claviers which Steinert has discovered in his searches covering a period of 40 years. The illustrations are supplemented by a minute description of each instrument. A concise history of the development of the piano and illustrations with explanatory text of Steinert's collection of violins, etc., complete the volume.

In "Reminiscences of Morris Steinert," compiled by Jane Martin, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New Yorkm 1900, Steinert gives interesting and amusing accounts of his experiences hunting old instruments in America and foreign countries. Steinert, a gifted and many-sided musician by profession, became a dealer in musical instruments, especially pianos, and founded the great house of M. Steiners & Sons, with headquarters at Boston and branch stores in leading cities of New England. The firm also controls Hume and the Jewett piano factories.

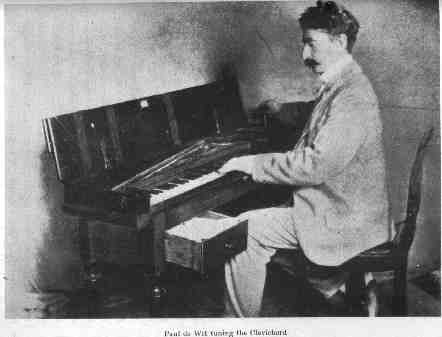

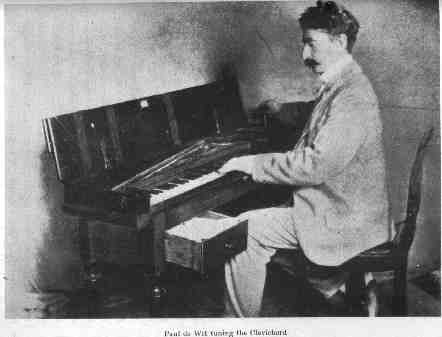

The "Katalog des Musikhistorischen Museums von Paul de Wit, Leipsic," published by Paul de Wit, 1904, is the most complete compendium in existence, describling old instruments of all kinds, their origin and makers. Although this catalogue is profusely illustrated, De Wit published in addition a most artistic album, "Perlen aus der Instrumenten Sammlung," von Paul de Wit, Leipsic, 1892. This album contain 16 illustrations printed in colors, each plate a master work of the color-printer's art. For the connoisseur, this album is a desirable and valuable addition to the library.

Paul de Wit has devoted his life to advance the interest of the piano industry. A sketch of his career is, therefore, only an acknowledgment of his valuable servivces. Born at Maastricht, Holland, on January 4, 1852, de Wit studied the cello under Massart at the conservatory of Luettich and showed decided talent. His parents objected to an artistic career and forced the young man to conduct a wholesale wine business at Aachen. Since the cello had a much more magnetic attraction for him than wine, he did not make a success of the wine business, and sold his interest in 1878. He went to Leipsic and became connected with the music publisher, C. F. Kahnt, where he made the acquaintatce of Liszt, vol Bülow, Carl Riedel, etc., and also the versatile Oscar Laffert. In partnership with the latter, he started in 1880, "Die Zeitschrift für Instrumentenbau," a dignified journal, devoted to the interests of the music trades of Germany. Laffert retired in 1886, and de Wit became sole proprietor of the publication, which to-day ranks amongh the most influential of trade journals in Germany and circulated in all civilized countries.

An artist, enthusiast and born collector, de Wit was not satisfied with his success as an editor and publisher, but set to work collecting ancient instruments of all kinds. He started a workshop with Hermann Seyffarth, the well-known repairer of violins and other musical insturments, in charge. Seyffarth rejuvenated the battered relics which de Wit had discovered during his travels, in storehouses, barns, garrets and cellars. De Wit virtually searched the Continent for old instruments, and many valuable discoveries stand to his credit. Whenever he heard that an old spinet, violin, bass drum or flute had been unearthed somewhere, de Wit would take the next train, no matter how great the distance or expense, to satisfy himself whether the relic was worthy of a place in his collection. As a result he assebled three collections, which are unrivaled. His first, containing 450 insturments, was bought in 1889 by the Government of Prussia for the Academy at Berlin. It was supplemented in 1891 by an addition of the grand piano used by Johann Sebastian Bach. His second collection of nearly 1,200 instruments was bought by Wilhelm Heyer of Cologne, who erected a special building to house his gems.

The industry owes to de Wit and Steinert a debt of gratitude for their unselfish labor in bringing to light the works of the old masters. Their efforts to again create a taste for the enchanting tone quality of the clavichord will bear fruit, by inducing the piano constructor of the future to search for a more pronounced combination of the liquid with the powerful tone than we find in the piano of the present.

Notable collections of ancient instruments are also found at the South Kensington Museum at London, in the Germanische Museum at Nuremberg, and in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, which latter has a genuine Christofori piano e forte. The most complete of all, however, is the unexcelled collection of Wilhelm Heyer at Cologne.

Report of the U.S. National Museum (1915)

site index

His studies in the realm of acoustics disclose a most penetrating mind capable of exact logical reasoning. He bases his conclusions on exaustive studies, without regard to the accepted theories of earlier scientists. As a thoroughly practical piano maker and master of his art, Hansing studied cause and effect in its application to the piano, and his book is a rich mine of information for the prospective piano designer and constructor. Free from any business affiliations, he treats his subject with an imparioan and unbiased keenness of perception which is at once impressive and convincing.

His studies in the realm of acoustics disclose a most penetrating mind capable of exact logical reasoning. He bases his conclusions on exaustive studies, without regard to the accepted theories of earlier scientists. As a thoroughly practical piano maker and master of his art, Hansing studied cause and effect in its application to the piano, and his book is a rich mine of information for the prospective piano designer and constructor. Free from any business affiliations, he treats his subject with an imparioan and unbiased keenness of perception which is at once impressive and convincing.