Perhaps we cannot present our readers a more interesting article on manufacturing, than to give an idea of piano-forte making. Piano-fortes, in these days, making an almost indispensable article of furniture in every dwelling; adding so much to the pleasures of home, and being so much of a companion in all home hours: contributing so largely to the enjoyments of society, that some little knowledge of the processes of making, and the materials used, must be not only interesting to all, but valuable to those who may wish to know how good piano-fortes should be made.

With this desire, we have selected as our model the large and flourishing manufactory of Messrs. Boardman & Gray, the eminent piano-forte makers of Albany, N.Y. celebrated as the manufacturers of the Dolce Campana Attachment Piano-Fortes, whose instruments were not only sought after and used by Jenny Lind, Catharine Hayes, and other celebrities, but by the profession generally throughout the United States.

Messrs. Boardman & Gray's manufactory is situated at Albany, N.Y., occupying the end of a block, presenting a front on three streets of upwards of 320 feet, the main building of which, fronting on two streets of 208 feet, is built of brick, four stories high above a high basement-story, devoted exclusively to machinery driven by a forty horse power engine. The completeness of design of these buildings and machinery for the propose used, we believe, has no superior, if any equal, in this country. Every improvement and convenience is attached to make the entire perfect, and in going through the premises one is attracted by the comprehensiveness of the whole concern.

The entrance to the factory of Messrs. Boardman & Gray is by a large gateway through the centre of the building, next to the office, so that the person in charge of the office has full view of all that enter or leave the premises. We pass into the yard, and are surprised at the large amount of lumber of all kinds piled up in the rough state. The yard is full, and also the large two story brick building used as drying sheds for lumber. Here a large circular saw is in full operation, cutting up the wood ready for the sheds or machine-rooms. Messrs. Boardman & Gray have the most of their lumber sawed out from the logs expressly for them in the forests of Alleghany, Oneida, Herkimer, and other choice localities in N.Y., and also Canada, and delivered by contract two and three years after being sawed, when well seasoned. The variety and number of different kinds of wood used in the business is quite surprising. Pine, spruce, maple, oak, chestnut, ash, bass-wood, walnut, mahogany, cherry, birch, rosewood, ebony, whiteholly, apple, pear-tree, and several other varities, each of which has its peculiar qualities, and its place in the piano depends on the duties it has to perform. The inspecting and selecting of the lumber require the strictest attention, long experience, and matured judgment; for it must be not only of the right kind, and free from all imperfections, such as knots, shakes, sapwood, &c., but it must also be well seasoned. All the lumber used by Messrs. Boardman & Gray, being cut two or three years in advance, is seasoned before they receive it; then it is piled up and dried another year, at least, in their yard, after which it is cut up by the cross-cut circular saw, and piled another season in their sheds, when it is taken down for use, and goes into the machine-shop; and here it is cut into the proper forms and sizes wanted, and then put into the drying-rooms for six months or a year more before it is used in the piano-forte.

These drying-rooms, of which there are three in the establishment, are kept at a temperature of about 100� Fahrenheit, by means of steam from the boiler through pipes. As fast as one year's lot of lumber is taken down for use, another lot is put in its place ready for the next year. In this way, Messrs. Boardman & Gray have a surety that none but the most perfectly seasoned and dry lumber is used in their piano-fortes. Their constant supply of lumber on hand at all times is from two to three hundred feet, and as Albany is the greatest lumber mart in the world, of course they have the opportunity of selecting the choicest lots for their own use, and keeping their supply good at all times.

The selection of the proper kinds of lumber, and its careful preparation, so as to be in the most perfect order, constitute one of the most important points in making piano-fortes that will remain in tune well, and stand any climate.

Here is the motive power, and a beautiful Gothic pattern horizontal engine of forty horse power, built at the machine works of the Messrs. Townsend of Albany, from the plans, and under the superintendence of Wm. McCammon, Esq., engineer now in charge of the Chicago (Ill.) Water-works. The engine is, indeed, a beautiful working model, moving with its strong arm the entire machinery used throughout the building, yet so quiet that, without seeing it, you would hardly know it was in motion. In the same room is the boiler, of the locomotive tubular pattern, large enough not only to furnish steam for the engine, but also for heating the entire factory, and furnishing heat for all things requisite in the building. Water for supplying the boiler is contained in a large cistern under the centre of the yard, holding some 26,000 gallons, supplied from the roofs of the buildings. The engine and boiler are in the basement (occupying the basement and first story in one room), at one end of the building, and are so arranged that all the machinery used in the different stories is driven throughout by long lines of shafting put up in the most finished manner, while the entire manufactory is warmed in the most thorough and healthy manner by steam from the boiler, passing through some 8,000 feet of iron pipe, arranged so that each room can be tempered as required. At the same time, ovens heated with steam through pipes are placed in the different rooms to warm the materials for gluing and veneering. The glue is all "made off" and kept hot in the different rooms by means of iron boxes with water in them (in which the glue-pots are placed), kept at the boiling point by steam passing through pipes in the water: thus the boiler furnishes all the heat required in the business.

We pass to the next room, where we find the workmen employed in preparing the massive metallic (iron) plates used inside the pianos, from the rough state, as they come from the furnace. They are first filed smooth and perfect to the pattern, then painted and rubbed even and smooth, and are then ready for the drilling of the numerous holes for the pins and screws that have to be put into and through the plate in using it. (A view of the drilling-machines and workmen is given with the engine.)

Into each plate for a seven octave piano, there have to be drilled upwards of 450 holes, and about 250 of these have pins riveted into them for the strings, &c.; and these must be exactly in their places by a working pattern, for the least variation might make much trouble in putting on the strings and finishing the piano. Of course, these holes are drilled by machinery, with that perfection and speed that can be done only with the most perfect machines and competent experienced workmen. And these metallic plates, when finished and secured in the instrument correctly, give a firmness and durability to the piano unattainable by any other method.

In the same room with the drilling-machines we find the leg-making machines, for cutting from the rough blocks of lumber the beautifully formed "ogee" and "curved legs," as well as sides, of various patterns, ready for being veneered with rosewood or mahogany. The body of the legs is generally made of chestnut, which is found best adapted to the purpose. The leg-machine is rather curious in its operations, the cutting-knives revolving in a sliding-frame, which follows the pattern, the leg, whilst being formed, remaining stationary.

Our first impression on entering the machine-shop is one of noise and confusion; but, on looking about, we find all is in order, each workman attending his own machine and work. Here are two of "Daniel's Patented Planing-Machines," of the largest size, capable of planing boards or plank of any thickness three feet wide; two circular saws; one upright turning-saw, for sawing fancy scroll-work; a "half-lapping machine," for cutting the bottom frame-work together; turning-lathes, and several other machines, all in full operation, making much more noise than music.

The lumber, after being cut to the length required by the large cross-cut saw in the yard, and piled in the sheds, is brought into this machine-room and sawed and planed to the different forms and shapes required for use, and is then ready for the drying-rooms.

In this machine-room, which is a very large one, the "bottoms" for the cases are made and finished, ready for the case-maker to build his case upon. If we examine them, we ill find they are constructed so as to be of great strength and durability; and, being composed of such perfectly seasoned materials, the changes of different climates do not injure them, and they will endure any strain produced by the great tension of the strings of the piano in "tuning up to pitch," amounting to several tons.

But we must pass on to the next room. We step on a raised platform about four feet by eight, and, touching a short lever, find ourselves going up to the next floor. Perhaps a lot of lumber is on the platform with us on its way to the drying-rooms. On getting on a level with the floor, we again touch the magic lever, and our steam elevator (or dumb waiter) stops, and, stepping off, find ourselves surrounded with workmen; and this is the "case-making" department. And here we find piano-forte cases in all stages of progress; the materials for some just gathered together, and others finished or finishing; some of the plainest styles, and others of the most elaborate carved work and ornamental designs. Nothing doing but making cases; two rooms adjoining, 115 feet long, with workmen all around as close together as they can work with convenience. Each room is furnished with its steam ovens, glue heaters, &c. The case-maker makes the rims of the case, and veneers them. He fits and secures these to the bottom. He also makes and veneers the tops. This completes his work, and then we have the skeleton of a piano, the mere shell or box. The rim is securely and firmly fastened to the strong bottoms, bracing and blocking being put in in the strongest and most permanent manner, the joints all fitting as close as if they grew together; and then the case is ready to receive the sounding-board and iron frame. The bottoms are made mostly of pine; the rims of the case are of ash or cherry, or of some hard wood that will hold the rosewood veneers with which they are covered. The tops are made of ash or cherry, sometimes of mahogany, and veneered with rosewood. We will now follow the case to the room where the workmen are employed in putting in the sounding-board and iron frames.

The sounding-board is what, in a great measure, gives tone, and the different qualities of tone to the piano. Messrs. Boardman & Gray use the beautiful white, clear spruce lumber found in the interior counties of New York, which they consider in every way as good as the celebrated "Swiss Fir." It is sawed out in a peculiar manner, expressly for them, for this use, selected with the greatest possible care, and so thoroughly seasoned that there is no possibility of its warping or cracking after being placed in one of their finished instruments. The making of the sounding-board the requisite thinness (some parts require to be much thinner than others) its peculiar bracing, &c., are all matters that require great practical experience, together with numberless experiments by which alone the perfection found in the piano-fortes of Messrs. Boardman & Gray, their full, rich tone giving the most positive evidence of superiority, can be attained.

We will watch the processes of the workmen in this department. One is at work putting in the "long-block" of hard maple, seasoned and prepared until it seems almost as hard as iron, which is requisite, as the "tuning-pins" pass through the plate into it, and are thus firmly held. Another workman is making a sounding-board, another fitting one in its place, &c. &c. All the blocking being in the case, the sounding-board is fitted and fastened in its place, so as to have the greatest possible vibrating power, &c.; and then the iron frame must be fitted over all and cemented and fastened down. The frame is finished, with its hundreds of holes and pins, in the drillers'-room, and the workman here has only to fit it to its place and secure it there; and then the skeleton case is ready to receive its strings, and begins to look like what may make a piano-forte.

Spinning the bass strings, and stringing the case, come next in order. In the foreground of the last plate, we have a curious-looking machine, and a workman busy with it winding the bass strings, a curiosity to all who witness his operations. To get the requisite flexibility and vibration to strings of the size and weight wanted in the bass notes, tempered steel wire is used for the strings, and on this is wound soft annealed iron wire, plated with silver; each string being of a different size, of course various sizes of body and covering wire are used in their manufacture. The string to be covered is placed in the machine, which turns it very rapidly, while the workman holds the covering wire firmly and truly, and it is wound round and covers the centre wire. This work requires peculiar care and attention, and, like all the other different branches in Messrs. Boardman & Gray's factory, the workmen here attend to but one thing; they do nothing else but spin these bass strings, and string pianos year in and year out.

The case, while in this department, receives all its strings, which are of the finest tempered steel wire, finished and polished in the most beautiful manner. But a few years since, the making of steel music wire was a thing unknown in the United States; in fact, there were but two factories of note in the world which produced it; but now, as with other things, the Americans are ahead, and the "steel music wire" made by Messrs. Washburn & Co., of Worcester, Mass. is far superior in quality and finish to the foreign wire. The peculiar temper of the wire has a great influence on the piano's keeping in tune, strings breaking, &c., and, as the quality cannot always be ascertained but by actual experiment, much is condemned after trial, and the perfect only used.

The preparation of what is termed the "key-board" is one of peculiar nicety, and the selection of the lumber and its preparation require great experience and minute attention, so that the keys will not spring or warp, and thus either not work or throw the hammers out of place, &c. The frame on which the keys rest is usually made of the best of old dry cherry, closely framed together to the form required for the keys and action. The wood of the keys is usually of soft straight-grained white pine, or prepared bass-wood. Both kinds have to go through many ordeals of seasoning, &c., ere they are admitted into one of the fine-working, finished instruments of Messrs. Boardman & Gray. The keys are made as follows: On a piece of lumber the keys are mark out, and the cross-banding and slipping done to secure the ivory; the ivory is applied and secured, and then the keys are sawed apart and the ivory polished and finished complete. The ebony black keys are then made and put on and polished, and the key-board is complete; the key-maker has finished his part of the piano. The ivory used is of the finest quality, and an article of great expense; its preparation from the elephant's tusks, of sawing, bleaching, &c., is mostly confined to a few large dealers in the United States. The most important concern of the kind is that of Messrs. Pratt, Brothers & Co., of Deep River, Conn., who supply most of the large piano-makers in the union. As the ivory comes from them, it is only in its rough state, sawed out to the requisite sizes for use, after which it has to be seasoned or dried the same as lumber, and then prepared and fastened on the key; then to be planed up, finished, and polished, all of which requires a great amount of labor, much skill, and experience. Besides ivory, Messrs. Boardman & Gray use no small quantity of the beautiful variegated "mother-of-pearl," for keys in their highly ornamental, finished piano-fortes, a material itself very costly, and requiring a large amount of labor to finish and polish them with that peculiar richness for which their instruments are so celebrated. In this, as in the other departments, each workman has his own special kind of work; nothing else to attend to but his key-making; his whole energies are devoted to perfect this part of the instrument.

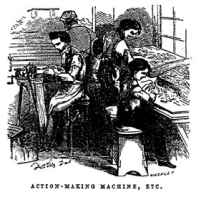

In this department, we again see the perfection of machine-work. The action is one of the most important things in the piano-forte. On its construction and adjustment depends the whole working part of the instrument; for, however good the piano-forte scale may be, or how complete and perfect all the other parts are formed, if the action is not good, if the principle on which it is constructed is not correct, and the adjustment perfect, if the materials used are not of the right kind, of course the action will not be right, and it will either be dead under the fingers, without life and elasticity, without the power of quick repetition of the blow of the hammer, or soon wear loose, and make more noise and rattling than music. Thus will be seen the importance of not only having that action which is modelled on the best principle, but of having an instrument constructed in the most perfect and thorough manner. All parts of it should be so adjusted as to work together with as much precision as the wheels of a watch.

Messrs. Boardman & Gray use the principle which is termed the French Grand Action, with many improvements added by themselves. This they have found from long experience to be the best in many ways. It is more powerful than the "Boston or Semi-Grand;" it will repeat with much greater rapidity and precision than any other; it is far more elastic under the manipulation of the fingers; and, to sum up all, it is almost universally preferred by professors and amateurs, and, what is still a very important point, they find, after a trial and use of it for many years, that it wears well. What is technically called the action consists of the parts that are fastened to the key, and work together to make the hammer strike the strings of the piano when the key is pressed down. The parts made of wood, consisting of some eight or ten pieces to each key, are what compose the action-maker's work; and, although they are each of them small, still on their perfection and finish depends much of the value of the instrument in which they are used. Various kinds of close-grained wood are used in their construction, such as white holly, apple or pear-tree, mahogany, hard maple, red cedar, &c., and other kinds as are best adapted to the use put to. They have to be closely fitted; the holes for the centre pins to work in must be clothed with cloth prepared expressly for this work. Buckskin of a particular finish, and cloth of various kinds and qualities, are used to cover these parts where there is much friction or liability to noise, and every part so perfectly finished and fitted that it will not only work smoothly, and without any sticking or clinging, but without noise, and yet be firm and true, so that every time the key is touched the hammer strikes the string in response. The action-maker completes these different parts of the action; and then another workman, who is called the "finisher," fits them to the keys and into the case of the piano; but, before we enter into his room, we will see to the preparation of another important part of the action, namely, the hammer. This is another extremely important thing in piano-forte making; the covering of the hammers is one of the most peculiar branches of the business. It is one that long experience and minute attention can alone perfect. The hammer head is generally made of bass-wood, and then covered with either felt prepared for this purpose, or deer or buckskin dressed expressly for this business. The preparation of buckskin for piano-forte makers is at this time quite an important trade, and the improvements made in its dressing of late years have kept full pace with the other improvements in the piano. The peculiar ordeal they undergo we cannot here explain; but we can only see the beautiful article finished for use. Some of them for the under coatings or layers are firm and yet elastic and soft, while those prepared for the top coating or capping are pliable and soft as silk velvet; and these, when correctly applied, will form a hammer which, if the piano-forte is perfect otherwise, will always give the rich, full organ tone for which the pianos of Messrs. Boardman & Gray are so celebrated. Those employed in covering and preparing hammers do this exclusively, and must perfect their work. They give the greatest number of coats, and the thickest buckskin to the hammers for the bass strings, and then taper up evenly and truely to the treble hammers, which have a less number of coats and of the thinnest kinds; and then, after the hammer is fitted to the string in the piano, and it has been tuned and the action adjusted, it goes into the hands of the hammer finisher, who tries each note, and takes off and puts on different buckskin until every note is good, and the tone of the piano is perfectly true.

We left the piano-case in the hands of the persons employed in putting on the beautifully polished steel strings, whose vibrations may yet thrill many a heart, or bring the starting tear. After it has its strings, it goes to the finisher, whose duties consist in taking the keys as they come from the key-maker, the action as prepared, and the hammers from the hammer-maker, and fitting them together and into the case, so that the keys and action work together; adjusting the hammer to strike the strings, and putting the dampers in their proper places to be acted on by the keys and pedals; making and fitting the harp, or soft stop; adjusting the loading of the keys to make a heavy or light touch, and thus doing what may be termed the putting the machinery together to form the working part of the piano-forte. And, when we consider that each key in one of Messrs. Boardman & Gray's piano-fortes is composed, with its action, of some sixty-five to seventy pieces, and that there are eighty-five keys to a seven octave instrument, making a sum total of nearly six thousand pieces, and that many of these pieces have to be handled over many times before they are finished in the piano, one is not a little surprised at the immense amount of work in a perfect piano-forte. But these six thousand pieces only compose the keys and action alone, and consist of wood, iron, cloth, felt, buckskin, and many other things; and, as a matter of course, each piece must be made and fitted with the greatest exactness, and the most perfect materials alone must be used.

The "finishing," it will be seen at once, is another important branch, and requires long experience, close attention, and workmanship. Messrs. Boardman & Gray have many workmen employed in this department at finishing alone. The work is done by the piece, as many of the different branches are under the personal superintendence of the foreman, whose duty it is to see that the work is made perfect; for the workman is liable for the materials he destroys. One great improvement made by Messrs. Boardman & Gray, and placed in all their piano-fortes, we believe is not used by any other maker. We refer to their metallic over damper and register and cover. The dampers are held in their places by wires or lifters passing between the strings and through the register, which holds them as they are acted on by the keys and pedal. This register is usually made in the old way, of wood, and placed under the strings, and, consequently, the weather acting on the wood is liable to warp or spring the register, and thus throw these wires or lifters against the strings, causing a jingling or harsh jarring when the piano is used; and, then, the register being placed beneath the strings, and the lifters passing through it above the strings to the dampers, of course they are liable to accidents, and to be bent and knocked out of place in many ways by anything hitting the dampers, as in dusting out the instrument, &c. But this improvement of Messrs. Boardman & Gray covers all these defects in the old register. Theirs, being of iron, is not affected by the changes of the weather or temperature of different houses and rooms; and, then, being placed above the strings, the dampers are at all times protected from injury. Consequently, their piano-fortes never have any jangling or jingling of the strings against the damper wires. This we believe to be a most valuable improvement, and, at the same time, the beautiful metallic damper cover is highly ornamental to the interior of the piano-forte.

When the case is thus finished, it can be tuned for the first time, although all is yet in the rough and unadjusted state; and from the finisher, after being tuned, it passes into the hands of the "regulator."

The Piano-forte Action Regulator adjusts the action in all its operations. Those parts are supplied and fitted that are still wanting to complete it. The depth of the touch is regulated, the keys levelled, the drop of the hammer adjusted, and all is now seemingly in order for playing; but in Messrs. Boardman & Gray's Factory, the instrument has to undergo another ordeal in the way of regulating; for, after standing for several days or weeks, and being tuned and somewhat used, it passes into the hands of another and last regulator, who again examines minutely every part, readjusts the action, key by key, and note by note, until all is, as it were, perfect. And now its tone must be regulated, and the "hammer finisher" takes it in charge, and gives it the last finishing touch; every note from the bass to the treble must give out a full, rich, even, melodious tone. This is a very important branch of the business; for great care and much experience are required to detect the various qualities and shades of tone, and to know how to alter and adjust the hammer in such a way as to produce the desired result. Some performers prefer a hard or brilliant tone; other a full soft tone; and others, again, a full clear tone of medium quality. It is the hammer-finisher's duty to see that each note in the whole instrument shall correspond in quality and brilliancy with the others. The piano-fortes of Messrs. Boardman & Gray are celebrated for their full organ tone, and for the even quality of each note; for the rich, full, and harmonious music, rather than the noise, which they make; and a discriminating public have set their stamp of approbation on their efforts, if we may judge by the great and increasing demand for their instruments.

The instrument, after being tuned, is ready for the ware-room or parlor But several smaller operations we have purposely passed by, as it was our wish to give a clear idea of the structure of the piano-forte by exhibiting, from stage to stage, the progress of the manufacture of the musical machinery. Let us now look after the construction of the other parts of the instrument.

The "leg-bodies," as they come from the machine, are cut out in shape in a rough state, ready for being veneered (or covered with a thin coating of rosewood or mahogany); and, as they are of various curved and crooked forms, it is a trade by itself to bend the veneers and apply them correctly. The veneers are carved and bent to the shapes required while hot, or over hot irons, and then applied to the leg-bodies by "calls," or blocks of wood cut out to exactly fit the surface to be veneered. These calls are heated in the steam ovens. The surface of the leg having been covered with glue, the veneer is put on, and then the hot call is applied and screwed to it by large hand-screws holding the veneer closely and firmly to the surface to be covered. The call, by warming the glue, causes it to adhere to the legs and veneer; and, when cold and dry, holds the veneer firmly to its place, covering the surface of the leg entire, and giving it the appearance of solid rosewood, or of whatever wood is used for the purpose. Only one surface can be veneered at a time, and then the screws must remain on until it is cold or dry; and, as the legs have many distinct surfaces, they must be handled many times, and, of course, much labor is expended on them. After all the sides are veneered, they must be trimmed, scraped, and finished, and all imperfections in the wood made perfect, ready for being varnished.

The desks are made by being so framed together as to give strength, then veneered, and, after being varnished and polished, are sawed out in beautiful forms and shapes by scroll saws, in the machine-shop. They have thus to pass through quite a number of processes before they are ready to constitute a part of a finished piano-forte. The same can be said of many other parts of the instrument that are made separate, and applied when wanted in the instrument, such as lyres, leg-blocks, or caps, &c. And, as each workman is employed at but one branch alone, and perfects his part, it is evident that, when put together correctly, the whole will be perfect. And, as Messrs. Boardman & Gray conduct their business, there are from twenty to twenty-four distinct kinds of work or trades carried on in their establishment. Thus, the case-maker makes cases; the leg-maker legs; the key-maker keys; the action-maker action; the finisher uts the action into the piano; the regulator adjusts it; and thus each workman bends the whole of his energies and time to the one branch at which he is employed. The result of this division of labor is strikingly shown in the perfection to which Messrs. Boardman & Gray have brought the art of piano-forte making, as may be seen in their superior and splendid instruments.

The putting together the different parts of the piano-forte, such as the top, the legs, the desk, the lyre, &c., to the case, constitutes what is called fly-finishing. The top is finished by the case-maker in one piece, and remains so until varnished and polished; then the fly-finisher saws it apart, and applies the butts or hinges, so that the front will open over the keys; puts on all the hinges; hangs the front or "lock-board" to the top; and completes it. He also takes the legs as they come from the leg-maker, and fits them to the case by means of a screw cut on some hard wood, such as birch or iron-wood, one end of which is securely fastened into the leg, and the other end screws into the bottom of the piano. The fly-finisher also puts on the castors, locks, and all the finishing minuti� to complete the external furniture of the instrument, when it is ready for the ware-rooms, to which it is next lowered by means of a steam elevator, sufficiently large to hold a piano-forte placed on its legs, together with the workman in charge of it.

The following plate exhibits a piano-forte on the elevator passing from the fly-finisher's department to the ware-rooms. Of these steam elevators there are two, one at each end of the building; one for passing workmen, as well as lumber, to and from the machine-shop and drying-rooms, and one for passing cases and pianos up and down to the different rooms. Much ingenuity is shown in their construction, being so adjusted as to be sent up or down by a person on either floor, or by one on the platform, who, going or stopping at will, thus saves an immense amount of hard labor.

Water from the Albany water-works is carried throughout the building on to each floor, with sinks, hose, and every convenience for the workmen, so that they may have no occasion to leave the premises during the working hours. One thing we must not forget to point out, and that is the Top Veneering-Press, made on the plan of "Dicks's Patent Anti-Friction Press" (shown in the following engraving on the upper floor at left hand), and we believe the only press of the kind in the world. It was made to order expressly for Messrs. Boardman & Gray, and its strong arms and massive iron bed-plates denote that it is designed for purposes where power is required. It is used in veneering the tops for their piano-fortes, and it is warranted that two men at the cranks, in a moment's time, can produce a pressure of one hundred tons with perfect ease. It is so arranged that the veneers are laid for several tops at one time. Tops made and veneers laid under such a pressure will remain level and true and perfectly secure. Messrs. Boardman & Gray have used this press upwards of eighteen months, and find that it works excellently, and consider it a great addition to their other labor-saving machines.

Having thus given a passing glance at most of the mechanical parts of the piano-forte, we will now examine the varnishing and polishing departments, consisting of some five or more large rooms. As the different layers of varnish require time to dry, it is policy to let the varnish harden while the workmen are busy putting in the various internal parts of the piano. Thus the case, when it comes from the case-maker, goes first to the first varnishing-room, and receives several coats of varnish; and, when the workman is ready to put in the sounding-board and iron frame, it is taken from the varnish-room to his department; and, when he has finished his work, it is again returned to the varnishing department, where it remains until the finisher wants it, who, when done with it, returns it to the varnishing-room. Thus, these varnishing-rooms are the store-rooms for not only the cases, but all the parts that are varnished; and the drying of the varnishing is going on all the time that the other work is progressing. In this establishment, from 150 to 200 pianos are being manufactured in the course of each day. In the varnish-rooms, from 100 to 150 cases are at all times to be seen; others are in the hands of the workmen in the different rooms, in the various stages of progress towards completion. Besides the cases in the varnish-rooms, we may see all the different parts of the pianos in dozens and hundreds, legs, lyres, tops, desks, bars, &c., &c., forming quite a museum in its way. The processes of varnishing and polishing are as follows: The cases, which are all of rosewood, are covered first with a spirit-varnish made with shellac gum, which, drying almost instantly, becomes hard, and keeps the gum or pitch of the rosewood from acting on the regular oil varnish. After the case has been "shellacked," it then receives its first "coat of varnish" and left to dry; and then a second coat is applied, and again it is left to dry. The varnish used is made of the hardest kind of copal gum, and prepared for this express purpose. It is called scraping varnish; it dries hard and brittle, and is intended to fill in the grain of the wood. When it becomes thoroughly dry and hard, these two coats are scraped off with a steel scraper. The case then receives several coats of another kind of varnish; when this is dried, it is ready for rubbing, which is effected by means of an article made of cloth fastened on blocks of wood or cork; and the varnish is rubbed on with ground pumice stone and water (a process somewhat similar to that of polishing marble). A large machine, driven by the engine, is used for rubbing the tops of pianos and other large surfaces. When the whole surface is perfectly smooth and even, it receives an additional coat of varnish. Each coat having become dry, hard, and firm, the surface receives another rubbing until it is perfectly smooth, when it receives a last flowing coat. After it is thoroughly dried and hardened, it is ready for the polishing process, which consists in first rubbing the surface with fine rotten stone, and then polishing with the fingers and hands until the whole surface is like a mirror wherein we can "See ourselves as others see us."

In the preceding statement, we have simply given an outline of the mechanical branches of the business, and a general description of the lumber required, and its peculiar seasoning and preparation prior to use. Large quantities of rosewood are used for veneering and carved work, slipping, &c. Just now, this is the fashionable wood for furniture; nothing else is used in the external finish of the piano-fortes of Messrs. Boardman & Gray. A view of their large veneer-room would excite the astonishment of the novice. Rosewood is brought from South America, and is at present a very important article of commerce, a large number of ships being engaged in this trade alone, to say nothing of the thousands employed in getting it from its native forests for shipping, and the thousands more busy in preparing it for the market after it has reached this country. Much that is used by Messrs. Boardman & Gray is sawed into veneers, and prepared expressly for them at the mills at Cohoes, N.Y. They buy large quantities at a time, and, of course, have a large supply on hand ready for immediate use. They always select the most richly-figured wood in the market, believing that rich music should always proceed from a beautiful instrument. Thick rosewood is constantly undergoing seasoning for those portions which require solid wood. And one thing, dear reader, we would say; and that is, where rosewood veneers are put on hard wood well seasoned, and prepared correctly, they are much more durable than the solid rosewood would be, not being so liable to check and warp. They also make use of a large quantity of hardware in the form of "tuning pins"�upwards of a ton per year. Of iron plates they use some twenty-five tons. Their outlay for steel music wire amounts to hundreds of dollars per year; not to speak of the locks, pedal feet, butts and hinges, plated covering wire for the bass strings, bridge pins, centre pins, steel springs, and screws of various kinds and sizes, of which they use many thousand gross annually. Of all these, they must keep a supply constantly on hand, as it will not do for their work to stop for want of materials. A large capital is at command at all times; and, as many of these things require to be made expressly to order, calculation, judgment, and close attention are needed to keep all moving smoothly on.

Cloth is used for a variety of purposes in the establishment of Messrs. Boardman & Gray. It is made and prepared expressly for their use, from fine wool, of various thicknesses and colors, according to the use for which it is designed. Whether its texture be heavy or thick, firm or loose, smooth or even, soft or hard, every kind has its peculiar place and use. Here we would give a word of caution to the reader. So much cloth is used in and about the action of the piano-forte, that we must beware of the insidious moth, which will often penetrate and live in its soft folds, thereby doing much damage to the instrument. A little spirits of turpentine, or camphor, is a good protection against them.

Ivory is another article which is largely used. Being expensive, no little capital is employed in keeping an adequate supply at all times on hand.

And then there is buckskin of various kinds and degrees of finish, sand-paper, glue, and a variety of other things, all of which are extensively employed in the business.

So far, we have treated merely of materials and labor. We have said nothing of the science of piano-forte making. If, after all the pains taken in selecting and preparing the materials required, the scale of the instrument shall not be correctly laid down on scientific principles; that is to say, if the whole is not constructed in a scientific manner, we shall not have a perfect musical instrument. So the starting-point in making a piano-forte is in having a scale by which to work. This scale must be of the most improved pattern, and laid out with the utmost nicety, and with mathematical precision. By the scale we mean the length of each string, and the shape of the bridges over which it passes. The length of the string for each note, and its size, are calculated by mathematical rules, and perfected by numerous experiments; and by these experiments alone can perfection be attained in the manufacture of the instrument. Messrs. Boardman & Gray use new and improved circular scales of their own construction, in which they have embodied all the improvements which have from time to time been discovered. They are determined that nothing shall surpass, if anything equals, their Dolce Campana Attachment.

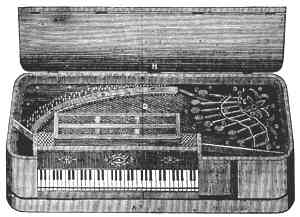

The great improvement of this age in the manufacture of the piano-forte is the Dolce Campana Attachment, invented by Mr. Jas. A. Gray, of the firm of Boardman & Gray, and patented in 1848 not only in this country, but in England and her colonies. It consists of a series of weights held in a frame over the bridge of the piano-forte, which is attached to the sounding-board; for the crooked bridge of the piano, at the left hand, is fast to and part of the sounding-board. The strings passing over, and firmly held to this bridge, impart vibration to the sounding-board, and thus tone to the piano. These weights, resting in a frame, are connected with a pedal, so that when the pedal is pressed down, they are let down by their own weight, and rest on screws or pins inserted in the bridge, the tops of which are above the pins that hold the strings, and thus control the vibrations of the bridge and sounding-board. By this arrangement, almost any sound in the music scale can be obtained, ad libitum, at the option of the pianist; and as it is so very simple, and in no way liable to get out of order, or to disturb the action of the piano, of course it must be valuable. But let us listen for ourselves. We try one of the full rich-toned pianos we have described, and, pressing down the pedal, the tone is softened down to a delicious, clear, and delicate sweetness, which is indescribably charming, "like the music of distant clear-toned bells chiming forth their music through wood and dell." We strike full chords with the pedal down, and, holding the key, let the pedal up slowly, and the music swells forth in rich tones which are perfectly surprising. Thus hundreds of beautiful effects are elicited at the will of the performer. This Dolce Campana Attachment is the great desideratum which has been required to perfect the piano-forte, and by using it in combination with the other pedals of the instrument, the lightest shades of altissimo, alternating with the crescendo notes, may be produced with comparative ease. Its peculiar qualities are the clearness, the brilliancy, and the delicacy of its touch. Those who, in the profession, have tested this improvement have, almost without an exception, given it their unqualified approbation; and amateurs, committees of examination, editors, clergymen, and thousands of others also speak of it in terms of the highest praise. Together with the piano-forte of Messrs. Boardman & Gray, it has received ten first class premiums by various fairs and institutes. And we predict that but a few years will pass ere no piano-forte will be considered perfect without this famous attachment.

We must now examine its structure and finish. The attachment consists of a series of weights of lead cased in brass, and held in their places by brass arms, which are fastened in a frame. This frame is secured, at its ends, to brass uprights screwed into the iron frame of the piano; and the attachment frame works in these uprights on pivots, so that the weights can be moved up or down from the bridge. The frame rests on a rod which passes through the piano, and connected with the pedal; and the weights are kept raised off the pins or screws in the bridge by means of a large steel spring acting on a long lever under the bottom of the piano, against which the pedal acts; so that the pressing down of the pedal lets the attachment down on to its rests on the bridge, and thus controls the vibrations of the sounding-board and strings. The weights and arms are finished in brass or silver. The frame in which they rest is either bronzed or finished in goldleaf, and thus the whole forms a most beautiful addition to the interior finish of the piano-forte.

Messrs. Boardman & Gray have applied upwards of a thousand of these attachments to piano-fortes, many of which have been in use four and five years, and they have never found that the attachment injured the piano in any way. As their piano-fortes without the attachment have no superiors for perfection in their manufacture, for the fulness and sweetness of their tone, for the delicacy of their touch and action, it may easily be seen how, with this attachment, they must distance all competition.

And now, dear reader, we have attempted to show you how good piano-fortes are made; to give you an idea of the varied materials which are requisite for this purpose; and to describe the numerous processes to which they are subjected, before a really perfect instrument can be produced.

The manufacturing department is under the immediate supervision of Mr. James A. Gray, one of the firm, who gives his time personally to the business. He selects and purchases all the materials used in the establishment. He is thoroughly master of his vocation, having made it a study for life. No piano-forte is permitted to leave the concern until it has been submitted to his careful inspection. If, on examination, an instrument proves to be imperfect, it is returned to the workman to remedy the defect. He is constantly introducing improvements, and producing new patterns and designs, to keep up, in all things, with the progress of the age.

The senior partner of the firm, Mr. Wm. G. Boardman, attends to the sales, and gives his attention to the financial department of the business. Thus, the proprietors reap the benefit of a division of labor in their work, and each is enabled to devote his entire time and energies to his own duties. Their great success is a proof of their industry and honorable devotion to their calling. They are gentlemen in every sense of the word, esteemed by all who know them, and honored and trusted by all who have business connections with them. They liberally compensate the workmen in their employ, and act on the principle that the "laborer is worthy of his hire." Their workmen never wait for the return due their labor. Their compensation is always ready, with open hand. The business of the proprietors has increased very rapidly for the last few years, and, although they are constantly enlarging and improving their works, they find themselves unable to satisfy the increasing demand for their piano-fortes. Their establishment is situated at the corner of State and Pearl Streets, Albany, N.Y., well known as the "Old Elm-Tree Corner."

Their store is always open to the public, and constantly thronged with customers and visitors, who meet with attention and courtesy from the proprietors and persons in attendance. We would advise our readers, should business or pleasure lead them to the capital of the Empire State, to call on Messrs. Boardman & Gray at their ware-rooms, even though they should not wish to purchase anything from them; for they may spend an hour very pleasantly in examining and listening to their beautiful and fine-toned piano-fortes with the Dolce Compana Attachment.

Instructions

Have your piano-forte tuned, at least four times in the year, by an experienced tuner; if you neglect it too long without tuning, it usually becomes flat, and troubles a tuner to get it to stay at concert pitch, especially in the country. Never place the instrument against an outside wall, or in a cold, damp room. Close the instrument immediately after your practice; by leaving it open, dust fixes on the sound-board and corrodes the movements, and, if in a damp room, the strings soon rust.

Should the piano-forte stand near or opposite a window, guard, if possible, against its being opened, especially on a wet or damp day; and, when the sun is on the window, draw the blind down. Avoid putting metallic or other articles on or in the piano-forte; such things frequently cause unpleasant vibrations, and sometimes injure the instrument. The more equal the temperature of the room, the better the piano will stand in tune.