Emily Rose's Story

Emily Rose's Story

Emily Rose's Story

Emily Rose's Storyby Jane,

her mother

When I became pregnant with my second child, I prayed that everything would go differently this time. I should have been more specific about what I asked for, because the first time, I left the hospital with a living child.

We wanted this pregnancy. I did all the "right" things. Because we use Natural Family Planning, we knew pretty much when we conceived. In fact, I went to the doctor to get tested too soon! I was sure because I was already having symptoms--the most welcome one the nonstop dreams I'd had every night of the nine months of my first pregnancy. The practice which had delivered my first baby had closed, thankfully, but the idiot who had done the delivery had moved to the only other area practice my insurance company paid. I didn't want to get that jerk again.

That was when I started saying I wanted everything to go differently. I read different books, and I changed my attitudes about prenatal care and testing. Because of the high false-positive rate, we didn't have an alpha-fetoprotein test performed, although we would have an ultrasound done. After all, an AFP test doesn't tell you about things that are correctable, but an ultrasound theoretically can.

That new practice was... Well, we changed insurance companies so I could ditch them. But then I didn't change practices right away. It took their refusal to test me for anemia (despite symptoms of anemia and a personal history of anemia) for me to finally walk out on them. It was only four days before the ultrasound was scheduled, but I no longer cared. The timing was an act of God.

I loved the third (and final) practice, where I was able to see certified nurse-midwives. (Because of their care, by the way, I will never again see an obstetrician/gynecologist. A CNM can perform any routine test a woman needs, and if there's a problem, you'll probably be referred to a specialist anyhow.) They approved an ultrasound just because my new insurance would pay for it--the old one wouldn't have. But everything was going so perfectly, they assumed we were fine.

At the time, I didn't know my body was telling

me something was the matter. My nonstop dreams had halted abruptly

in mid-November, about four weeks into the pregnancy. Before

the exam where the doctor was going to try to hear the heartbeat

for the first time, I was so terrified that I didn't bring my

son to the appointment. I wasn't telling acquaintances--and this

was a real break from my first pregnancy. Plus, week after week,

I wasn't gaining weight. I'd try my hardest, but even after the

first trimester and its morning sickness passed, the weight wouldn't

come on.

I had a good ultrasound technician. I'm sure, in retrospect, that she must have seen it outright, but she kept up the conversation until time came to take the measurements. Then she told us to stay in the room for a moment, because last week the computers hadn't processed the images correctly and some couples had needed to come back--she'd just check and return in a minute. I sat up and chatted to my husband about how well that had gone. And then the technician returned with another radiologist.

I went totally cold. I asked if something was the matter. He said no, just lie back and he'd retake the measurements.

Then he asked, had I had an AFP test?

When he turned on the machine again, he went right for the head. I knew there were only a few things an AFP test looks for, other than twinning: Down's syndrome, spina bifida, and anencephaly. I must be one of only a few women in the world who's ever prayed that her child had Down syndrome.

At the beginning of the pregnancy, wondering the way I do about everything in the world, I remembered an article called "Stephen's Prayer" from two years earlier in the Couple To Couple League's Family Foundations newsletter. In it, a couple had a baby diagnosed with a fatal abnormality, whom they carried to term. I remember thinking to myself that their baby had anencephaly (although looking it up later, I found I was wrong). I remember thinking to myself, "What would I do if my baby had anencephaly?" Without hesitation, I had responded to myself, "I'd have to carry it to term anyhow."

When I couldn't take the tension any longer, I said to the radiologist, "What is it?"

He said, "Anencephaly."

I whispered, "No brain?"

My husband gasped and turned around. I went utterly numb. I don't really remember what happened immediately after that, but I asked how sure he was. He said 100% sure. When was the last time a medical person said "100%" about anything? I knew something about anencephaly. I knew it was incurable. I knew there was no danger to me. I knew it meant our baby would die. In retrospect, I don't know how I knew these things, where I'd read them and why I'd remembered.

The two radiologists said they'd leave us alone in the room for a bit while they went to call the midwife. I said, "Tell her we're not going to terminate."

The radiologist said, "I'm only going to--"

I was like a madwoman. "Tell her we're not going to terminate!"

They left us alone. James and I talked quietly

and held one another. I couldn't believe it--and yet I could.

I don't know what I was feeling, if I even felt anything. I was

scared and desperate and terrified--but not in denial. For some

reason, I never doubted it was

all happening.

reason, I never doubted it was

all happening.

We got to see the doctor. Because we'd suddenly become a "high risk" case, we were seeing one of the practice OBs. She wasn't very nice. That's all I can say about her character. I think she was mad that we'd taken the choice out of her hands about whether to terminate. She tried to scare us. She said things like "These babies are pretty hideous" (you're not Miss America yourself, honey) and "If we don't induce, you could carry her for fifty-five weeks" (gee, I always wanted to be in the Guiness Book of World Records.)

The radiologist hadn't taken any pictures from the scan. She hadn't found out the gender. I guess she thought it wasn't important. It left me feeling that much more desolate: not only was I not going to have a baby, but now I didn't even have something to hold onto or a way to know about this baby I was going to lose. I was already thinking, "I want my baby back."

That night was...horrible. I stayed up playing the shareware game Solitaire Till Dawn, and my husband played games of his own. Even after going to bed exhausted, I only slept a few hours. In the middle of the night, I woke up and thought about the baby's name. If it was a girl, I didn't want to give her the name we'd planned. I've since found out this isn't the best tactic to take, but I went for a second-string name my husband had liked during the first pregnancy. Emily. And what about a middle name? All of a sudden it came to me, Rose. No boys' names presented themselves to me at all. When my husband woke up in the morning, I said to him, "Emily Rose. If it's a girl." He said, "All right."

The next day, when

I cried about not having ultrasound pictures, my husband called

the clinic and asked for copies. The radiologist said we could

come back and take more pictures for free. It took five minutes

of the woman's lunch hour, but I'm sure she's going to heaven

for that simple kindness. She showed us the anencephaly in more

detail, how the top of the head had simply failed to form above

the eyebrows. She took three pictures. And she determined that

our baby was a girl.

The next day, when

I cried about not having ultrasound pictures, my husband called

the clinic and asked for copies. The radiologist said we could

come back and take more pictures for free. It took five minutes

of the woman's lunch hour, but I'm sure she's going to heaven

for that simple kindness. She showed us the anencephaly in more

detail, how the top of the head had simply failed to form above

the eyebrows. She took three pictures. And she determined that

our baby was a girl.

We got a second opinion. The second radiologist spent 45 minutes confirming the obvious. We saw a genetic counselor, and we saw a specialist in high risk cases. Everyone we met at Dartmouth Medical Center was superb. They were a teaching hospital, and they obviously attracted the highest calibre professionals in their specialties. They never tried to scare us or to push us to terminate. When we returned for the follow-up consult with the OB at home, her snide and condescending nature repulsed us. I switched back to the midwives, and that was that.

We got the diagnosis at twenty-two weeks. I've since met individuals who got their diagnosis at twelve weeks or even earlier. They have my sympathies. We had four months to prepare, and I felt that was just about the right amount of time for us. We had time to prepare our toddler son for what was happening, introduce him to the concept of death, and encourage as much sibling bonding as was possible and proper for his age. I took care of ten million details, just about all of which are preserved somewhere on this site. I joined support groups. I learned every single thing I could about anencephaly.

We prayed. We asked others to pray. They asked others to pray. We estimate our daughter had 750 people praying for her! And I know God answered our prayers. So many things that could have gone wrong, didn't go wrong. The very fact that I'd switched practices before getting the news showed me that God was guiding us. Coincidences, good feelings, and loving support from everyone around us demonstrated that God was going through this at our sides. What I wanted most of all, I might not get, but at least we weren't struggling all alone, and that meant Emily's anencephaly had a purpose. Hers wouldn't be a wasted life.

I had only one chance

to love Emily while she was still in the world. Only 20 more

weeks. We tried to take advantage of all of them.

I had only one chance

to love Emily while she was still in the world. Only 20 more

weeks. We tried to take advantage of all of them.

Emily had her own personality. I didn't understand before those months how a mother could bond before birth--but I tried. How much was imagination and how much fact, I can't tell. But she seemed stubborn. Although the medical professionals asserted she would be both blind and deaf, Emily reacted to sound. More than that, she could react in specific ways to specific words I said! She disliked noise, and she jabbed furiously when I turned over at night. She kept my husband awake by kicking him when we cuddled, and yet she held totally still whenever her brother touched my tummy. She put us in mind of Mary in The Secret Garden, solemnly telling Colin, "If everyone thought I was going to die, I wouldn't do it." And we hoped not--we sincerely hoped not.

At 27 weeks, I had what I thought was preterm labor. I managed to get it stopped, but that incident renewed my frenzy to ready everything for my daughter's arrival. By 38 weeks, the details were all taken care of. I was at term. Emily wasn't ready to come out, though. The due date passed. Finally, we set the induction date for 42 and a half weeks.

I can't describe how comforting the midwives were. Throughout the pregnancy, they never treated me shoddily just because my baby had a fatal anomally. I received top-notch care and generous understanding. Never was I criticized for carrying my baby to term. They were more than happy to give a little extra hand-holding when I fretted about the fundal height or too-frequent braxton-hicks contractions. I was very, very impressed.

We arranged for all three sets of Emily's grandparents to come to town for her birth. We began the induction at 10 in the morning on July 19th. By 10 that night, I still hadn't dilated even though I was having regular contractions a minute apart. I wasn't in pain; in fact, I was sitting up in bed reading! The midwife gave me a warm-up dose of pitocin, and it was like igniting rocket fuel. Emily was born at 11:08pm. The birth itself was everything I had wanted it to be--everything my first birth was not. I was unmedicated and in control, and I delivered squatting the way I wanted. I felt Emily kicking all the way. Right before I pushed her out, I could feel her turn in the birth canal, and I told everyone she was still moving.

She emerged into the world purplish-grey, still, silent, and not breathing. The nurses slipped a cap on her head and laid her unmoving body in my arms. My husband quickly grabbed the jar of Lourdes water by my bedside and pronounced the words of a conditional baptism. "If you are able to be baptized, I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit."

Abruptly she gasped, and I exclaimed, "You're

alive!" The nurses sprang into action, suctioning her and

doing other  things I can't

remember. I was so delighted she was alive. I remember seeing

with disappointment that all our prayers hadn't healed her, but

it didn't matter at that moment. She was here. I was holding

her. She was alive. She was Emily Rose, my daughter. It was all

I wanted.

things I can't

remember. I was so delighted she was alive. I remember seeing

with disappointment that all our prayers hadn't healed her, but

it didn't matter at that moment. She was here. I was holding

her. She was alive. She was Emily Rose, my daughter. It was all

I wanted.

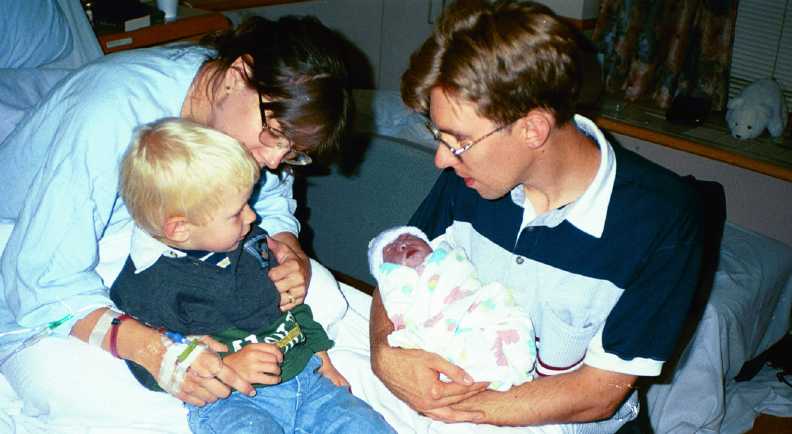

My husband called the family, and they came. Everyone got a chance to hold her, including my son. He still tells me about how he held his sister. We had borrowed a friend's camcorder, and my brother took the video while Emily went around the room and met everyone. The hospital's Catholic chaplain came and confirmed her. Everyone took pictures, rolls of pictures. I remembered looking at some of the photos online and saying, "How can these people be smiling?" But there I was, holding my daughter and smiling. I had Emily, for however briefly. Why wouldn't I smile?

Emily remained with us for two precious hours. During that time, she had an attitude of paying careful attention to all of us. She opened only one eye, but she did seem to have some hearing because she reacted to my voice and the things I said. She was bleeding from her head, though, and in the end she couldn't hang on. I told her that if she had to go, it was all right--she could go. A little after one in the morning, just as the video tape ran out, she left us.

It wasn't until after Emily was dead that I really inspected her. She had all the right numbers of fingers and toes. She had huge feet, just like her brother, and perfect piano-player hands with long fingers and pretty fingernails. Her eyes were brilliant cobalt blue, and her hair was dark brown. She weighed six pounds, fifteen ounces, and was nineteen and a half inches long. Her mouth was covered with nursing blisters, I suppose from sucking her fingers in utero, but I couldn't find a matching callous on her hands. Her ears were pressed hard to the sides of her head, also like her brother's had been. Her eyes bugged out a bit because the orbital bones had failed to form properly. I finally had the courage to remove her cap and look at the damage to her head. Her face stopped right above the eyes: she had no eyebrows at all. In back, though, she had incredibly good skull formation for an anencephalic. There was an open part at the top, about as big as the circle of my thumb and forefinger. Her brain was exposed, covered only by a thin membrane. I could tell her brain had hemispheres--the doctors had been wrong when they said only her brain stem would form. She'd had a sucking reflex. She'd had hearing. She might have understood who we were. I looked desperately to find a birthmark on her, wanting something else to remember her by--some feature that was distinctly Emily--but there was none.

The rest of the details are important to me and not so important to anyone else: the night she spent in the bassinet in the hospital room, my husband and I holding her for one extra hour in the morning before letting the nurse take her away, the funeral director bringing her to us cradling her in his arms... What I remember is how many people showed their support and how many people made the effort to reach out to us. It's never easy to bury a child, but I think everyone's presence made it less than impossible.

I don't understand yet why Emily had to die.

I don't know if I ever will answer the question to my own satisfaction.

Even if I  did, I'm sure that

answer would satisfy no one else. I know I've met some very charitable

and generous people because of Emily and because we share the

same sad situation of losing a child. I hope someday to be able

to help others the way I was helped during my time of crisis.

I do feel blessed by the opportunity to share some of my life

with such a charming and individual little girl. I wouldn't trade

my time with Emily even if it meant I could have a healthy baby

instead. In the beginning weeks, we tried to get through day

to day and week to week, meeting the issues as they arose, creating

a new normal out of the shards of the old, and preserving our

daughter's memory. Now, months afterward, I can understand how

I've learned more from her than I ever believed it possible to

be taught by one little girl.

did, I'm sure that

answer would satisfy no one else. I know I've met some very charitable

and generous people because of Emily and because we share the

same sad situation of losing a child. I hope someday to be able

to help others the way I was helped during my time of crisis.

I do feel blessed by the opportunity to share some of my life

with such a charming and individual little girl. I wouldn't trade

my time with Emily even if it meant I could have a healthy baby

instead. In the beginning weeks, we tried to get through day

to day and week to week, meeting the issues as they arose, creating

a new normal out of the shards of the old, and preserving our

daughter's memory. Now, months afterward, I can understand how

I've learned more from her than I ever believed it possible to

be taught by one little girl.

Thank you for visiting Emily Rose's memorial web site.

You are also invited to visit our Carrying To Term web pages (tips for carrying to term, but also more photos and anecdotes about Emily). Otherwise, you may want to continue exploring the anencephaly web-ring. Please feel free to email me if you wish.

For more information about carrying to term, anencephaly, or bereavement issues, please see my links and resource pages.

No content follows: just webring banners and some web awards this page has received.

pieces of spam email if you accepted

a Geocities cookie.

pieces of spam email if you accepted

a Geocities cookie.