![]()

SPIRIT OF

ALBANIA

|

Anthony

Weir Edith

Durham Ivanaj

Brothers King

Zog Norman

Wisdom and Albania Skenderbeg Gazetteer

|

|

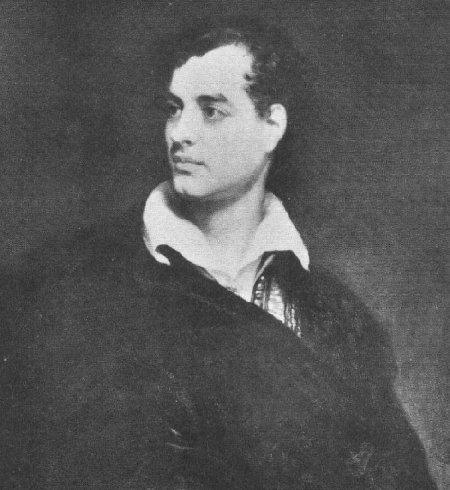

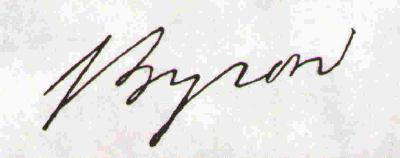

LORD BYRON (1788-1824)

George Noel Gordon Byron was born at Holles Street, London, Jan. 22, 1788, and he died serving Greek independence, at Missolonghi, April 19, 1824. His father was Captain John Byron of the Guards, a profligate officer, who eloped to France with a divorcée, and then married again in order to get the money to pay his debts. His great-uncle, whose title the poet succeeded to, killed a neighbor in a drunken brawl, was tried before the House of Lords, and acquitted. He then conducted himself so badly as to gain the sobriquet of "wicked Lord Byron." The poet's grandfather was Admiral Byron, known as "Foul-weather Jack," who had as little rest on sea as the poet on land, and who had the virtues without the vices of the race. The family of Byrons distinguished themselves in the field; seven brothers fought in the English Civil War battle of Edgehill.

No literary branches of any note grew from the family tree of the Byrons untill the birth of our author, excepting that in the reign of Charles II there was a Lord Byron who wrote some good verses. One writer has tried to find a poetic ancestry for our author by connecting the Byrons of the 17th century with the family of Sidney. Byron's mother was Catherine Gordon, heiress of Gight in Aberdeenshire in Scotland. "The lady's fortune was soon squandered by her profligate husband, and she retired to the city of Aberdeen, to bring up her son on a reduced income. The little lame boy, endeared to all in spite of his mischief, succeeded his great-uncle, William, and became Lord Byron, in his eleventh year." The happy mother sold off her effects and went with her son to Newstead Abbey. This estate had been conferred on Sir John Byron by Henry VIII following the seizure and destruction of the monasteries, and Charles I had ennobled the family as a reward for high and honorable service in the Royalist cause during the Civil War. While Byron came from an honored and noble ancestry, he was unfortunate in his parentage. Deserted by his father, he was left to the uncertain training of a mother who was moved by the extremes of indulgent fondness and vindictive disfavor. In her fits of anger, he was her "lame brat," and her discipline consisted in throwing things at him; while in her pleasant moods he was her "darling boy," and the recipient of her kisses. Between these extremes she lost all control over him. He became self-willed and resisted all efforts to control him by sullen resistance or defiant mockery. This characteristic followed him through life, and, without doubt, may be traced to his parental training.

Upon succeeding to the earldom, the youth was sent to Dulwich School (South London), and thence to Harrow. In 1805 he was removed to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied for about two years. His school life was not particularly brilliant. He gained large stores of general information, but made little progress in his classical studies. The head master of the school at Harrow received him as a "wild northern colt," very much behind his age in Greek and Latin. According to his own account, he was always rebelling and getting into mischief; yet he managed to keep up his reputation for general information by reading every history he could get hold of, and by studying the English classics. Perhaps the most profitable time of his life was the year's vacation spent at Southwell with the Pigotts. The genial encouragement which they gave him expanded his poetic impulses and marked the dawn of his genius. While at Harrow he had been busy scribbling verses, and the admiration expressed by the Pigotts led him to publish a collection entitled "Hours of Idleness." Upon his return to Cambridge, he found his volume well received. The applause which it gained encouraged him to make literature a profession. He accordingly made a careful examination of himself, including his acquirements. The rest of his college life was spent in collecting his powers to make a grand struggle for fame. In 1808 a savage attack was made upon him in the Edinburgh Review. It is said that Byron never acted except under the influence of love or defiance. The attack in the Review stirred the poet to action, and the scorching satire "English Bards and Scotch Reviewers" was the result. It is understood that Lord Brougham wrote the criticism, but Byron's reply was a complete punishment of the objects of his wrath. This was Byron's first literary battle, and he could have said, as did the hero of Lake Erie, "We have met the enemy, and they are ours." With the wreath of triumph still fresh on his brow, the young lord started, in 1809, for a tour of the continent. For two years he wandered over Spain, Albania, Greece, Turkey and Asia Minor.

For some time after his return, he lived at Newstead very unhappily, but he busied himself correcting the proof sheets of "Childe Harold." Finally he went to London to enter politics. He took his seat in the House of Lords, and spoke two or three times on important measures. In the spring of 1812 the first two cantos of Childe Harold appeared in print. It gained instantaneous and widespread popularity. "I awoke one morning," he said, "and found myself famous." The effect was not confined to England; Byron at once had all Europe as his audience, because he spoke to them on a theme in which they were all deeply concerned. He spoke to them, too, in language which was not merely a naked expression of their most intense feeling; the spell by which he held them was all the stronger that he lifted them with the irresistible power of song above the passing anxieties of the moment." A moment's call upon our historic memories will show why Childe Harold pleased all Europe. It appeared about the time Napoleon set out for Moscow. It was with difficulty that an English army could defend itself in Portugal, and the English nation was trembling for its safety. The movements of the dreaded Bonaparte were being watched by all eyes, and every state in Europe was shaking to its foundation. At such a time as this, Childe Harold "entered the absorbing tumult of a hot and feverish struggle, and opened a way in the dark clouds gathering over the contestants through which they could see the blue vault and the shining stars." In his second canto, Byron turned from the battlefields of Spain, With

blood-red tresses deepening in the sun, to "august Athena," "ancient of days," and the "vanished hero's lofty mound," thus placing before the world the departed greatness of Greece. Young Lord Byron became the lion of the hour, and the center of London society. In 1813 he produced Giaour,and The Bride of Abydos; 1814, The Corsair, and Lara; 1816, The Siege of Corinth and Parisina. Omitting the rest of his social life till the close of this sketch, well will now finish, in brief, the record of his principal literary work. Leaving England, he spent the remainder of his life at Geneva, Venice, Ravenna, and in other parts of the continent.

In 1816 appeared the third canto of Childe Harold and The Prisoner of Chillon; in 1817: Manfred, The Lament of Tasso, and Beppo. In 1818 he wrote the Ode to Venice, Mazeppa, and he completed the epic Childe Harold. In 1820 he translated the first canto of Morgante Maggiore, The Prophesy of Dante, Francesca de Rimini, Marino Faliero, and The Blues (a regiment not a mood). From 1821 to 1823 he finished the epic and influential Don Juan, and wrote Sardanapalus, Letters on Bowles, The Two Foscari, Cain, Heaven and Earth, Werner, Deformed Transformed,The Age of Bronze," and The Island. Music-lovers will recognise many of these titles, for they inspired works by Tchaikovsky, Berlioz and Richard Strauss - and perhaps the amazing painting by Delacroix of The Death of Sardanapalus, king of Assyria. Having been appointed by the Greeks (who were not the ethnically-cleansed people then that they are now) Commander-in-chief of their expedition to Lepanto, he was about to embark upon his duties when he was taken sick. All efforts to save him failed, and he died in 1824. For Byron, "Greece" was not so much a territory as an idea. He would have considered Albania to be "Greece" at a time when the largest Albanian city was Ianinna (then an important Ottoman center of administration and now the regional capital of Epirus) and Albanian was spoken as far south as the then-small town of Athens. The Greece that achieved independence was only a fraction of the size that it is now, after a century of expansion and attempted land-grabbing (the two Macedonian Wars of 1912 and 1913), and the forced "assimilation" of Slavs and Albanians, whose languages are still suppressed in the "Hellenic Democracy" that is part of the European Union. Byron's love affairs were numerous, but in 1815 he married Miss Milbanke, a northern heiress, and daughter of Sir Ralph Milbanke. Ida, an only daughter, was born in the following December. Lady Byron left him in about one year, and refused to return. Their union seems to have been unfortunate, as they were ill-suited to each other. His Farewell to Lady Byron is a poem of much tenderness, sincerity and regret. The social disapproval ("mad, bad and dangerous to know" as Lady Caroline Lamb famously declared) depression and financial misfortunes that settled upon Lord Byron caused him to leave his native land forever, to seek quiescence through adventure on the Continent of Europe. In many respects Byron's life echoes that of Burns - the one a lord, the other a landless laborer - but both singularly brilliant and unfortunate; loved and despised, and both dying from venereal disease in the very prime of life. Though little-read now, because of the heroic style and length of his works, "his genius will be a source of wonder and delight to all who love to contemplate the workings of human passion in solitude and society, and the rich effects of taste and imagination.

"When we see his uncontrolled passions lifted into great surging billows, like the wild unrest of the ocean, and then see him penning his farewell to his wife and child, while the tears are falling like rain upon the paper as he writes, we cannot find it in our heart to write unkindly of him. We simply repeat what Joaquin Miller said: BURNS AND BYRON. In men whom men condemn

as ill

|