Blitz, May, 1985

Morrissey interviews long-time heroine Pat Phoenix, until recently Coronation Street's Elsie Tanner.

Photographs by John Stoddart

never turn your back on mother earth

Morrissey interviews Pat

Phoenix

Blitz, May, 1985

Morrissey interviews long-time heroine

Pat Phoenix, until recently Coronation Street's Elsie Tanner.

Photographs by John Stoddart

She

says she was never the Hollywood type; she says she's stopped reading the

newspapers; she loves science fiction; she loves Dynasty and Hill

Street Blues ("for comic relief"); she reads five novels per

week; she shrugs with exhausted compassion for Elsie Tanner, who clings like an

irksome relative.

She

says she was never the Hollywood type; she says she's stopped reading the

newspapers; she loves science fiction; she loves Dynasty and Hill

Street Blues ("for comic relief"); she reads five novels per

week; she shrugs with exhausted compassion for Elsie Tanner, who clings like an

irksome relative.

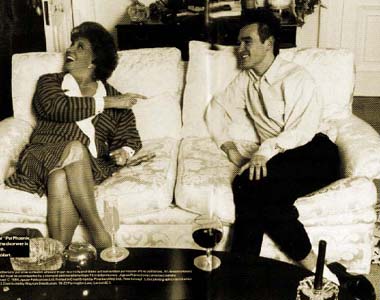

Here in her agent's home overlooking the great charm of Alderley Edge, Pat

smokes and she drinks and she's all over the room. Her friends love her

and her love is returned. As the photographer lines up another shot, Pat

confronts the camera with precise professionalism. No amount of evidence

will make me believe that Pat Phoenix is 61 years of age. It's impossible.

Born in St Mary's Hospital in Manchester in 1924, she hammered her way through

decades of theatre work until, in 1960, at the age of 36, she found

instantaneous worldwide stardom playing Elsie Tanner in Granada Television's

twice-weekly drama Coronation Street.

Elsie was the screen's first 'angry young woman'; a wised-up, tongue-lashing

cylindrical tempest, sewn into cheap and overstuffed dresses, harnessed by

severe poverty, staunchly defending her fatherless children, devouring a

blizzard of temporary husbands in dour Salford council dwellings. It was

the skill of Pat's acting that earned Elsie great distinction as mother, sister

and lover to millions.

Twenty years later, Pat left Coronation Street. Vanishing with

her sanity intact, she returned to her first love, the stage. "Most

people think of what they're about to lose," she would claim, "but I

always think of what I'm about to gain."

MORRISSEY: How did you get the role in The L-Shaped

Room (1962) and why did you accept it?

PAT PHOENIX: I was with Granada at the time and there was

a stipulation in my contract which said that I wasn't allowed to do anything

without their permission. So one day Bryan Forbes range me up and said he

had a part in a film for me, and I trekked off and did the film in four days

without telling anybody.

M: Were you bothered by the nature of the role?

PP: No. If you bear in mind that I started off in

theatre all those years ago playing roles like Sadie Thompson. No, it

didn't bother me at all.

M: Film at that time, was in a very exciting mood.

Was it ever tempting to prolong your film career?

PP: While I was contractually tied to Granada, there were

seventeen film parts offered to me. But I couldn't take them because they

wanted me to work for long stretches.

M: In retrospect, would you gladly have forfeited your

life as a television star for that of a film star?

PP: Not really, because my world is the theatre. I

was brought up in the theatre and I made my own way. I was in theatre for

many years before I was in television. I never thought that mine was the

sort of face for either television or film. I prefer theatre. You're

on your own.

M: For an audience, television is intimate whereas

theatre isn't. On television you can clearly see the expressions in an

actor's eyes.

PP: In theatre you make your own close-ups. Your

close-ups are yours to command. Stage is most exhilarating. you know

when an audience loves you. You know when they are restless. When an

audience is with you, it's a wonderful feeling. You never know on

television.

M: How risque was it to take on the part of Sadie

Thompson?

PP: Oh well, that's a classic. I played her

hundreds of times in stock. I had my hair full of gold powder, you know.

M: Was that a very brazen thing to do?

PP: Not Sadie Thompson, but there was one which was

particularly brazen. I went out on the first of the Sex Crime tours called

A Girl Called Sadie; there are a few very naughty photographs of me

around, for those times. It was just, again, a part, and the further the

part is away from yourself the bigger the challenge to play it, and that's where

the excitement is. I played everything. When I was twenty-two I

played ninety-year-old women. I don't know how convincingly I played

them... It's always better to play nasty parts than it is to play nice

parts because there's more meat on them.

M: Is there more scope for women than men in theatre?

PP: Well, there used to be. But things are all

going to pot these days. In the 1940's they started writing up men's parts

for women, but I'm afraid the women have lost their hold over the last ten to

fifteen years. It needs to come back.

M: Wasn't that simply linked to the war, when women had

to take over traditionally male roles, and then were hammered back into

insignificance once the war was over?

PP: No. I think that the Americans were very quick

to assess the matriarchal society, and that women in the lead consequently

brought more women into the cinema, who in turn brought more women. And

that's really the same in the theatre. The vast majority of theatre

audiences are women. Terence Rattigan knew that years ago. We need

writers to write bigger and better parts for women again - once writers stopped

doing that, the cinema lost its audience.

M: What was it like to work for Joan Littlewood's theatre

company?

PP: She was... experimental.

M: How did she treat her players?

PP(laughs): Very harshly.

Nobody was beautifully paid. You barely had enough to exist on. Joan

and I clashed because I thought she was a lot of sounding brass and not enough

violins, and violins are very important in the theatre. She nursed the men

- like Richard Harris and James Booth. But she was very hard on the women

- women like Yootha Joyce and Barbara Windsor.

M: How do you think theatre stands now. Do people

care?

PP: People would care if theatre became more localised

again. Theatre now is too damned expensive. In our biggest theatres

the cheapest seats are f7.50, and half our people are unemployed! The

average person in the street would love to see a good play. But how can

they at those prices?

M: Does that make it a terribly middle-class affair?

PP: Oh, I hope not. I shall be going out this week

on a 20-week tour, and I hope the costs of the seats won't be too high.

M: But do you have any control over that side of it?

PP: No, I haven't. But since I don't ask for an

enormously sensational salary they don't have to charge extra to see me.

Art belongs to us all and art should be available to us all.

M: Do you think that people see theatres as places which

are being closed down, or turned into DIY centres, and therefore a sphere which

is dying?

PP: I've got a great deal of faith in the young.

And remember, everyone up to the age of 29 is a youngster to me. I really

believe that this generation is going to unspoil all the things that my

generation have spoiled.

M: How interested were you in politics as a teenager?

PP: Not at all. I was very light-headed. If

you were in theatre then that was your life and you were totally dedicated.

Mine are the politics of morality - and I'm not talking about sex. If

you've any compassion at all - and most artists should if they're not posing -

then you care about people and you care about this planet, and THAT'S what my

politics are. I take the side of the underprivileged.

M: You recently met Royalty. What were your

impressions, if any?

PP(wry smile): I've met quite a

few of them. PA-wise, they do a good job. But I never really think

about it. Our kings for hundreds of years were elected, they were not

hereditary. William The Conqueror started this hereditary line. But

before that they were elected. And what a jolly nice idea.

M: You are a Patron for Cruelty Against Circus Animals.

PP: Cruelty against ANY animal. And if you're going

to ask me if I've got a fur coat the answer is YES. I've had it for 25

years.

M: Is it real?

PP: Most of my modern coats are not real, but I do have a

fur coat that my mother gave to me and I have no intentions of parting with it.

M: How much affinity do you feel with Ireland now?

PP: All of us who are half-Irish... who have the basic

Irish... are born with the celtic twilight in us. That moody celt, the

obvious rebel, stays within us all, and we never change, whatever our loyalites

to the place in which we live.

M: How do you feel about central Manchester now?

PP: You mean the 'rape' of Manchester. The skyline

of Manchester was totally Gothic at one time. And that can never come

again. The small houses that were pulled down could have been saved and

modernised.

M: Is there anything left to be preserved?

PP: There are things to save if they care to. We

call those Hulme flats 'the Inca dwellings'. Destroying even the mills is

destroying part of our essential history.

M: In a sense, do you feel that all is slipping away?

PP: Yes. But I'm such a firm believer in youth, and

I don't think the young people are going to let it all be destroyed. If

anybody asks me who I'd like for Prime Minister I'd say David Bellamy.

M: Do you find that, as an artist, there's a limit to the

strength of the public statements you might make about politics?

PP: Yes I do.

M: What holds you back?

PP: I'm slightly headstrong. I don't want to see a

revolution in this country. I'd like to see a mental revolution. I'd

like to see the kids being given what really belongs to them.

M: How difficult is it to be in the situation where any

strong political comments you make would be front page news?

PP: Well, it has been, as you know. I had a letter

on Nightline the other night, someone wrote in and said, "as for you, Pat

Phoenix, you're nothing but a Communist supporting Tony Berin, and a Luddite

supporting Arthur Scargill" ... I'm not even faintly pink.

M: Do people write to Pat Phoenix or to Elsie Tanner?

PP: To Pat Phoenix... now. Sometimes women

in the street will come up and say, "eeh, Elsie - oh sorry, it's Pat, isn't

it." But it's a great compliment. It's not an insult.

M: Is there a point where The Street and the whole

discussion of Elsie becomes tiresome because you've moved on?

PP: Yes, yes, yes. Let's get the situation clear.

I earned my living for twenty years in Coronation Street. For the

first eight to fifteen years it was terribly exciting because the character was

expanding. Mea Culpa - the fault is mine. After a time I

thought there was no place Elsie could go; the character was finished, as far as

the scriptwriters were concerned. I personally could see no place that she

could go - barring the Salvation Army. I was told that it was absolute

madness to leave the programme at my age because, quite frankly, I didn't know

what was going to happen next or where I should go. But I preferred to

take my chance.

M: When you first left The Street the ratings fell, and

then you returned and the ratings soared. Did you feel a magnificent

responsibility to keep the ship afloat?

PP: No. I felt slightly embarrassed.

M: Why?

PP: Because I always believe that a team is a team is a

team. I don't know what 'star' means. I only know I'm a working

actress.

M: Was there never the feeling that, with being the

anchor of The Street and also its public face, it all fell on your shoulders?

PP: No. All actors are real, live human beings.

The satisfaction for me was when one' s colleagues came up and said, "damn

good effort, Pat", but never to believe that you did it all yourself,

because you didn't.

M: Who did you most admire in The Street?

PP: Arthur Lowe was a very good friend, and also Diana

Davis, who is now with Emmerdale Farm. It isn't a question of

admiring talents. What you really admire is people as human beings.

M: Do you think Granada are very conscious of your

comments now?

PP: They shouldn't be. I don't make comments about

the programme now. I'm in no position to. I've always been totally

loyal. I'm too close to it to make any judgement. I can only ay

that I was bored with what they were doing with Elsie. In earlier days,

when Tony Warren and Jack Rosenthal wrote the scripts, the programme was alive

and it was vital.

M: Were the scripts ever wrong for Elsie?

PP: I often thought so.

M: Could you tell who was writing the script by the mode

of the storyline?

PP: In the old days, very easily! But we only have

five basic stories in the whole of the world. And these are what we had to

work on. So, in Coronation Street, stories were repeated with

different variations on theme. I had had enough. While I was bored

I was not doing my best.

M: What was Violet Carson (Ena Sharples) like to

work with?

PP: Somebody said of Violet that going into the Street

was the worst thing that ever happened to her. She had done Shakespeare

and was going into the very straight side of things. She did have her

crotchety moments.

M: Off camera as well as on?

PP: Yes. She would get highly irritated by changes

in the programme, and rightly so.

M: Can you comment on incidents when, as with Peter

Adamson (Len Fairclough) and Peter Dudley (Bert Tilsley) for

instance, actors' lives become very public with national newspaper attention?

PP: It's very depressing. There's always much more

to these things than people see. None of us are infallible. We are

all subject to some slight or big sin, whatever it is. I do think that

around that time the newspapers were deliberately battering the Street.

M: Why would you say the newspapers wanted to see the

Street on its knees?

PP: Well, don't you find that, throughout history, people

build something on a great pedestal, and then the fun is in pulling it down?

At a certain time a Coronation Street exclusive would guarantee huge

newspaper sales.

M: How did you feel when Peter Adamson sold his stories

to the press, making his private life with the cast of The Street very public?

PP: He won't be the first and he won't be the last.

I was one who was hurt by all that. But there are two sides to his

stories, and I honestly believe that he needed the money.

M: In The Street, did the 'part' ever crush the 'person'?

With cases like Peter Dudley and Frank Pemberton (Frank Barlow),

did their demise within the Street crush them as individuals?

PP(evasively): I was only Elsie

Tanner. The character had overtones of me in it, and overtones of my

mother. Next season I play a zany English woman, and while I'm playing it

I'll probably be a zany English woman. But I lose it when I'm finished

with it. It's gone with Sadie Thompson, Blanche Dubois, Katherine

Hernshawe, all the parts of my youth.

M: How difficult was it to be pinned to an image of a

woman with mountainous sexuality?

PP: Hysterical.

M: But was it funny?

PP: Sometimes it was bloody awful.

M: What were the expectations?

PP: Everybody was having bets as to how they were going

to maul Elsie Tanner. Absolutely horrifying in some cases. I've

never been a promiscuous woman. When you add it all up, I loved for love's

sake and never for money or what I could gain. Usually, I lost.

Elsie was acting. Let's face it, I've never been a great beauty.

I've always been slightly over-weight. With Bette Davis, who was

attractive but never beautiful, when she said onscreen, "I am Jezebel and I

am beautiful," you believed it, and that's acting.

M: Do you think it will take a new formidable television

role for you to escape the Elsie harness?

PP: Yes. I hope Elsie will always be remembered

with affection in the nation's history. But I want to move on. I

want to take up all roles, whether it's a 90 year-old hunchback or a faded

Mae West.

M: What do you look for in a new script? Is

sexuality important?

PP: What is sexuality? Very often warmth and

compassion are mistaken for sexuality. I often wonder. Oh yes, I

could thrust the thigh and fling the left boob, but that's an actress' equipment

and you must use it. Recently in a play a young man and I were talking and

he accidentally hit me in the chest and I said, "It's perfectly alright,

just acclimatise yourself with the props." Anna Magnani had what I

would call 'sexuality', in the very force of her passion, and I mean passion

about LIFE. She was alive and she was living and you felt you could rush

into her bosom and she would embrace you. I don't know what Page Three

sexuality is; I never did.

M: What kind of role would be wrong for you?

PP: You can't say that ever. My next part might be

an alcoholic old tramp molesting young men in the street. This is what

we're about, playing other people. Most actors get rid of so many

inhibitions by playing other people.

M: Do feminist ideals ever register with you when

considering your next manoeuvre?

PP: I've always been liberated. A woman who has

always earned her own living, who has never had anyone to support her - apart

from my mother - and who has had to go in like a man and be as good as a man and

be better than a man. I was the first of the anti-heroines; not

particularly good-looking, and no better than I should be. Oh yes, the

casting couch exists - for men as well as women. And I know that with many

feminists when you're trying to force a point you sometimes have to go over the

top. But it will take another two centuries to truly liberate women,

because men are so hopelessly brainwashed.

M: How do you see your books, in retrospect?

PP: Certainly no threat to Shakespeare. I am in my

books as I am on the stage, an entertainer. I don't think I'm a 'great'

writer.

M: You once christened yourself Patricia Dean after James

Dean, didn't you?

PP: My stepfather's name was Pilkington, and so I had to

use Pilkington to keep peace in the family. I used it in the theatre until

one theatre manager said to me, "Bloody awful name you've got there, love.

Are you any connection wtih Lady Helena of the glassworks?" and I said,

"No, I'm not", and he said, "Well you can't go around with a name

like bloody Pilkington, can you?", and so he suggested I change it to Dean

after James Dean.

M: In earlier days you lived in Finsbury Park.

Could you easily acclimatise yourself to London?

PP: London is a place for when you are rich and famous.

When I lived there I lived in abject poverty. Our window overlooked the

railway. It was very depressing because I was totally unknown.

M: Could you ever live there?

PP: No, I don't think so.

M: Are you chained to the North?

PP: Not chained. I would move to Cornwall or

Sussex.

M: Do you like travelling abroad?

PP: I'm a Sagittarian. We love to travel but we

hate to arrive.

M: Of your collection of paintings, which is your most

valuable and which is your most treasured?

PP: I haven't any valuable paintings at all. Most

of them have emotional value. I haven't any masters. Or mistresses

for that matter.

M: Do you care about modern art?

PP: I like anything I can understand. It's a gut

feeling. Some paintings make me cry.

M: What about modern music?

PP: Some of it excites me. I think a lot of modern

music is taken - perhaps without knowing it - from classical music. So

much of it has symphonic overtones.

M: If you could choose your next stage role, what would

it be?

PP: I'd like to do Catherine the Great. She was

such a glorious pig (laughs).

M: How do you feel about television plays?

PP: I think there's been a sway away from kitchen sink.

People are struggling now, going without heat and light. They

should be able to watch plays that entertain and transport. It is most

essential that people are transported.

M: Have people changed in their needs and desires?

PP: Oh yes. We had the era of the angry young man.

But we're all angry now. Not just some of us. In my generation

Terence Rattigan was the person spoke for everybody.

M: As a person who was the voice of Manchester council

dwellers, what do you feel for that situation now?

PP: I have not honestly seen a two-up-and-two-down that

was not a little palace.

M: What about high-rise?

PP: I hate to look at them from the outside. I

despair of that whole thing because England is not a place for skyscrapers.

We're used to living in houses, not up in the air. It's the wrong

psychological image for England.

M: Do you think this is why so many people are unhappy

now?

PP: Yes I do. There are so many places where we can

still build houses and people can still have a little plot of land. Space

is so important for people. We all need space, however poor we are.

M: Do more bad things happen in life than good things?

PP(gravely): Aw no, no, no, no,

no, no! I think we all must have our share. But I'm a great

reincarnationist. Life is a lesson and we all must learn, and the next

time you'll have the same set of problems but you'll know how to deal with them.

I don't believe you come back once; I believe you come back hundreds of times.

Yes, bad things happen in life. But a lot of life is what you bring to

yourself. I believe in good vibrations. If you're with someone who

puts out bad, depressive feelings, then you should try to help, and then move

away.

I've talked to millions of people who feel that they have no hope for the

future, and I just want to put my arms around all of them. The miners'

wives who have the soup kitchen going are so dedicated, and I'd say to them,

"Is it ever going to be the same when the men go back to work?" and

they'd say, "Oh no, we're a community now!" And see, even in the

face of hunger they had found something.

You're always very sad when you're young. I've known this since my first

very weak attempt at suicide. But now, I could fall down tomorrow and

break my neck, but that's OK, that's all part of it.

I am now 61. And I don't believe it. I still wanna throw my bonnet

over the windmill and I still wanna do mad things and rush into the sea at

midnight.

This article was originally

published in the May, 1985 issue of Blitz.

Reprinted without permission for personal use only.