|

HISTORY OF No. 304 (POLISH) SQUADRON

Written by Wilhelm Ratuszynski

When in

the summer of 1940, two Polish bomber squadrons – Nos. 300 and 301 – were by

now fully engaged in action, many more personnel who trickled in from France,

were ready to continue the fight and be involved with the RAF. They were sent to

Bramcote, which already became squadrons forming station.

On 23 August 1940, part of them officially formed No. 304

(‘Silesian’) Bomber Squadron. The unit’s original roster totaled 185

people, including 31 officers. Most of the flying personnel saw action in Polish

campaign with reconnaissance squadrons of the 2nd Air Regiment (Cracow) and the

6th Air Regiment (Lwow), and with French Army in France.

W/Cdr Bialy became unit’s first CO having W/Cdr W. M.

Graham as British adviser. The squadron received NZ code letters and

usual 16 Fairey Battles for training. As a unit it was attached to the 1 Bomber

Group.

At the beginning, the squadron ‘s personnel had to overcome

many obstacles in its preparations for a service. Main hindrances were lack of

instructors and language barrier. The Battle of Britain was in its culminating

moments and it was justified that a training bomber squadron received little

attention. Soon after Bramcote welcomed another Polish bomber squadron to form–

No. 305 – on September 1st, the training was sped up thanks to collective

efforts of personnel of both units. At the same time, maintenance and technical

personnel went through conversion courses at RAF Hucknall.

By the time the unit started conversion to Wellingtons

in December the Poles made a great progress considering they were new not only

to the aircraft, but also to the language, regulations, and even to the country.

Airmen learned tons of theoretical and practical instructions, litany of

drill-manuals and regulations, as well as every detail of their aircraft. Only

after many long hours working as a harmonious team, a crew could expect to be

sent on their first operational sortie. As the other Polish airmen demonstrated

it previously, the Poles of No. 304 Squadron were able and more then willing to

quickly turn themselves into effective operational unit.

With the new aircraft the No. 304 was transferred to Syerston,

near Newark on December 1st. In Syerston, the number of flying personnel doubled

and continued preparations for active service. The process did not always go as

smooth as it could and there were some indignation. In result, on December 21,

W/Cdr Dudzinski replaced the CO. But soon things

were beginning to look better. The crews benefited from a large, pre-war

aerodrome where they found reasonable comfort, the one that could be expected

during the war. Occasional leaves, airmen took as enjoyable breaks: visits to

neighboring British squadrons, Poles at Swinderby, and to inevitable local pubs.

Many converged on the "Flying Horse" in Nottingham, after their short

visits to Hucknall and Newton where Polish pilots’ schools were operating.

Before its

first operational sortie, the 304 suffered its first lost. During low flying

exercise, one Wellington lost power on both engines simultaneously and pilot

crash-landed in hilly terrain. F/O Christman, Sgt Pietruszewski and Sgt Berger

were killed.

On the night of 24th/25th April 1941, No. 304 squadron took

part in the combat mission for the first time. F/O Sym and F/Lt Czetowicz flew

two "NZ" Welligtons that took off to bomb fuel damps in Rotterdam.

During incoming days all the other squadron’s crews had a chance to unload

over the enemy’s territory and their targets were: Cologne, Brest, Osnabrück,

Düsseldorf, Mannheim, Bielefeld, Frankfurt, Essen and Nuremberg. Slowly, Poles

were building up invaluable experience, increasing the squadron’s operational

level. With raised number of sorties came unavoidable losses. In May unit lost

three full crews, one of which was the one of British adviser W/Cdr Graham shot

down over Bremen. Luckily, the 304 suffered relatively small losses in comparing

to the other RAF units which flown Wellingtons, and always maintained a full

complement of aircrews. The hardship of flying mission over continent became a

routine and excitement of being in the combat unit among airmen was lost gone.

On June 11, the top brass from the group visited both 304 and 305. Two days

later, Poles at Syerston had an honor to be visited by H.R.H.

the Duke of Kent. On July 16, the unit received following note form AOC of the No. 1 Bomber

Group:

"On the occasion of the celebration of the Polish Air Forces Day I wish

to congratulate the Polish squadrons 304 and 305 and station personnel on the

splendid work they have done, and say how proud I am to have such excellent

fighting and technical personnel under my command. I wish you all the very best

of luck for the future."

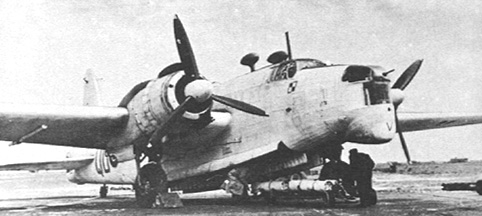

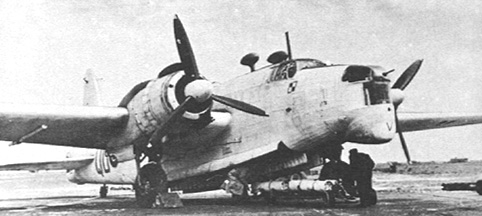

Wellingtons Mk. IC of No. 304 Squadron. The

"Q" R1245 in May 1941.

Now the 304 took its firm place in the general plan of operations of

the 1st Bomber Group. Crews were often out on raids for three successive nights.

In July, August and September unit flew many missions over the Rhur suffering

only one loss. On July 24, the crew of complete freshmen was lost over Emden –

in July the unit totaled 52 sorties. Four days earlier, the No. 304 was

transferred to Lindholme in York, and the move practically did not hinder a bit

the squadron’s operations.

During second half of the year the 304 continued to build its good record,

but registered normal operational losses. On October 20 (Emden), one crew was

lost after their aircraft was shot down near Helgoland. On 26th (Hamburg), one

damaged Wellington ditched near Cromer, and except one airman the crew was found

and saved by Air-Sea Rescue boat. Three crews went to bomb Manheim on November

7th. In adverse weather conditions, one plane had to force-land when it was out

of fuel. Pilot, F/Sgt Blicharz saw illuminated airfield and thinking he was over

England, put the aircraft down. This happened to be a German airfield near

Brussels. Realizing its location, the crew quickly set the aircraft on fire

before being captured.

When on November 14th, W/Cdr Poziomek took over the squadron’s command;

five crew sortied for a raid on Hamburg. One crew ditched damaged aircraft near

Yarmouth and floated for one day in dinghy before being rescued. Less lucky was

crew of Flight "A" commnader, S/Ldr Blazejewski. All were killed on

December 17th over Ostende.

In 1941, No. 304 totaled 214 operational sorties for 1202 hours.

The unit

lost 47 airmen killed, missing or POW.

During the first months of the 1942, the squadron was heavily involved

in the Allies bomber offensive. Although the RAF’s superiority in the air was

established, the Luftwaffe defenses were far from being weak. They improved

significantly. Germans applied many different countermeasures and the bomber

losses mounted. Being in the thick of the clash, the 304 did not escape its

share of wounds. The unit’s airmen resources were slowly eroding and the

replacements were scarce.

For No. 304 April proved to be a tragic month. Squadron lost six crews (36

airmen) during missions and toward the end of the month could hardly muster six

or seven aircraft for operations. Important day was 24th April 1942. One year

earlier the first operational flight had been made, and General Sikorski visited

the unit. See

pictures. A big reunion of former and present members of the squadron was

staged, but the duty was not be interfere with. Some of those who came to

celebrate decided to volunteer for that night’s mission to Rostock, and beef

up depleted flights. Crews were shuffled ad hoc, and seven NZ Wellingtons

took off. The attack was a success. All the bombers

took off right on schedule, reached their targets and unloaded on burning city,

and returned safely.

The next day the Polish C-in-C made the following entry in the

Squadron’s log:

"On this first anniversary of No. 304 Squadron whose splendid service

has added so much to the fame of Polish arms, I convey to the officers and other

ranks of the Squadron my best wishes for the future. May your magnificent flight

over Germany on the night of April 24th – 25th presage further crushing

victories until this war for Poland is won."

This NZ-Q is DV441. Probably RAF Lindholme, early 1942.

Heavy losses sustained by the Polish bomber force in April, together

with corresponding lack of reserves – particularly painful was the shortage of

navigators – threatened PAF with decision to suspend operations. It was

decided in the Bomber Command that one of the Polish bombers squadrons would

have to be transferred to Coastal Command, where as a rule, losses were lighter

but the crews carried out longer tours of duty without relief. Having suffered

especially heavy losses during its 488

operational sorties, and desperately needing to lick its wounds, the 304

Squadron was chosen. The official reassignment took place on May 10th.

- With Coastal Command –

The only good thing the vast

majority of No. 304 crews saw in the transition, was a better chance to survive

missions. The first impression on almost everything else seemed to be bad. The

new airbase was on the tiny Isle of Tiree in the Western Isles, only a few miles

wide and less than 20 miles long. The place

looked howling and under constant onslaught of capricious Atlantic weather.

There were virtually no navigational aids. Living

quarters were mere Nissen huts, always dump and rattling under heavy winds.

The airmen had no previous experience of flying over the sea,

which differ a lot from bombing raids. To get the feel of it, many strenuous

hours of patrolling in gray monotony were needed. Generally low marine knowledge

of aircrews was a hindrance in the squadron’s conversion. Most of the Polish

airmen never even saw a submarine, and one crew attacked a solitary rock of

Rockall jutting out of the sea some 300 miles west of Scotland. Despite all

this, the transition from the Battle of Germany to the Battle of the Atlantic

fared well.

No. 224 (RAF) Squadron flying Hundsons was also

stationed on Tiree. Few days after their arrival, Poles got to know theirs

British colleagues, and immediately a healthy, friendly rivalry was born: who

would sink the first U-boat. Soon the great comradeship by the British was

displayed, when their CO had all his aircraft ready within half an hour, for a

search of one Polish Wellington ditched in the Atlantic. Read more.

On May 18th, 1942, S/Ldr Poziomka made the first operational sortie, a

six-hour patrol over Atlantic’s Western Approaches. From that day on, Polish

Wellingtons were regularly taking off for U-boat hunting. On 26 May, the crew of

navigator F/O Skarzynski spotted and attacked a U-boat, which was the first

attack of that type by Polish aircraft. British Admiralty believed it to be a

successful one and that the U-boat had been damaged. Read more.

Flying long sea patrols was anything but easy. To detect an enemy sub,

crews had to fly low over water, which was an arduous and distressing activity.

Rarely saw they sun, and grayish sky cohered with a dull sea depriving them of

the sense of horizon. This caused an illusion of slowly flying into the sea. In

addition, the crews had to be constantly vigilant looking for enemy boats or

aircraft. This service was strenuous and monotonous. After those sorties, came

debriefing and meal, after which, tired crews hardly ever sought something other

then rest.

One month after arrival at Tiree, on June 13, the No. 304 was transferred to 19 Group and to RAF Dale, in

South Wales. Although the stay at the lonely island was short and unappealing,

the departure was somewhat emotional. Station CO, G/Cpt Tuttle, arranged for the

Coastal Command band to come all the way from England, to play the 304 off to

the mainland. Poles thanked him for benevolent leadership and hospitality. Two

weeks later, W/Cdr Poziomek received this letter from G/Cpt Tuttle:

“I must write and express my appreciation to you

and the whole of your Squadron for their magnificent work here. I was amazed the

whole time at the enthusiasm with which they tackled anything, and at their

cheerful acceptance of the living conditions here. Before 304 Squadron came I

was very worried because I thought you would all dislike the place intensely and

would probably dislike the work, and was delighted to see that you apparently

liked both. I cannot imagine any station commander having an easier job than

having 304 Squadron at his station, and only hope that I shall meet you all

again some time. I hope you will remember me to everybody in the Squadron; I

shall never forget them and shall be delighted to have anybody up here when they

can come.

If you ever have time, do let me know how things

are going at Dale, as everybody here is asking if I have heard about the

Squadron, which everybody here misses.”

The squadron’s new area of operations became the Bay of Biscay. Except

patrolling, escorting transatlantic convoys became the new duty. From Dale crews

flew more intensely, but in much better weather conditions. The Battle of the

Atlantic was in a full swing and the crews’ work was more demanding, although

little they realized the gravity of the state of affairs. Patrols exhausting.

Common complain was eyestrain, caused by glaring waters of these

habitually sunlit seas. The menace of enemy’s fighters was much more serious

here, but the chances to hunt a U-boat were far better.

On the night of June 25/26th, seven NZ Wellingtons were prepared for the

RAF’s 1,000 bombers raid on Bremen. Selected crews flew over to Docking, where

their aircraft were refueled and loaded with bombs. One squadron’s Wellington

was shot down killing all crew.

Summer of 1942 started to look like a very busy time

for No. 304. Operational sorties were flown daily. All this hard work, however,

paid little in terms of success. In July, only three times Poles encountered and

attacked U-boats:

- July

6. The crew of F/O Nowicki dropped six depth charges on submerging U-boat

without any results.

- July

10. The crew of F/O Krzyszczuk probably damaged one during its periscope run.

- July

30. Another crew unsuccessfully depth-charged submerging U-boat.

During

this period, daily news of raging battle over East Atlantic, reminded Poles that

they were in a thick of it. No. 304 Squadron’s resources were stretched to the

limits. Flying anti-submarine patrols, night bombing attacks on U-boat bases in

French ports, convoy escorting and other smaller duties, kept the crews hard at

work. Ground crew did not have any easier time. Rapidly ageing aircraft Bristol

Hercules engines were causing more and more frequent problems. It is worth to

notice, that at any point during that time, the unit’s losses or difficulties

did not undermine its operational value.

An August of 1942 was not going to be any less

laborious. The squadron’s work was highlighted with few events:

- On

August 3, the crew of F/O Zarudzki spotted and attacked submerged ship. After

the attack, oily spots and large amount of air babbles were seen.

- On

the 9th, the crew of F/O Figura caught surfaced U-boat, but to its great despair

was unable to jettisoned depth charges.

- On

the night of August 12, the one of the most experienced crew was lost in a first

night sortie. Read more.

- On

August 13, the crew of navigator F/O Nowicki sunk U-boat in position 47N/10W.

Three depth charges fell very close to the surfaced German ship, which begun to

list to the port and later submerged. British Admiralty confirmed it as

destroyed, although no confirmation was found after the war.

On September 2, the crew of F/Lt Kucharski surprised another U-boat and

was credited with enemy’s ship damaged. Coastal Command aircraft begun to be a

serious menace to U-boats, and Germans devoted more long-range Ju-88 and Me110

fighters to patrol over the Bay of Biscay. Sooner or later Polish Wellingtons

were bound to encounter them. This happened on September 5, when the NZ-C

piloted by sergeants: Bakanacz and Twardoch skirmished with two Junkerses. Read

more.

On the 16th, the crew of NZ-E had to face even greater

odds, when their aircraft was attacked by six Ju-88s. Poles fought off obviously

inexperienced Germans neatly and valiantly, to return to the base victorious. Read

more.

Unusual luck for meeting enemy’s aircraft over the

seas had pilot F/Sgt Bakanacz. When on September 24, nine Polish Wellingtons

patrolled their sector; his crew was attacked by two Ju-88s. Together with his

commander F/O Morawski they outmaneuvered the attackers and the gunners battered

them. Two weeks later Bankacz was in a strange skirmish with a four-engine Focke

Wulf 200 of the notorious “Condor” unit. The encounter took place some

15 miles north of the Spanish coast. Gunner Sgt Kubacik exchanged few scratches

with the Germans and the Poles disengaged.

On October 16 the real misfortune saddened the

unit’s airmen. In the morning, very popular and outstanding officer, F/O

Targowski received a letter from his wife in Poland, the first news of her since

his departure from Poland in 1939. In high spirits, he took off for a late

morning patrol, and two hours later the station received a telegram stating that

he was awarded a DFC. Two pieces of great news called for a celebration. A party

was being organized when the signal from his aircraft was received that it was

under attack. Shot down by a German fighter, the whole crew perished. Similar

fate met another crew on November 1st.

Worsening weather conditions lessen a little bit

number of sorties, and the last weeks of 1942 were uneventful. On Christmas Eve

five crews took off for sorties. Meantime, the weather closed in and the base

was unserviceable. Wellingtons were directed to another airfield and four of

them landed safely. The fifth crew had bail out as their aircraft used-up last

drops of fuel, after being airborne for 11 hours and 36 minutes. All five Polish

crews made it back to the dale and in time for a party. During that evening, No.

304 Squadron activities in Coastal Command were summed up by the squadron and

station COs. The unit did very well and the Poles had all the reasons to be

proud of their service.

During

these seven months, the squadron totaled 549 sorties during almost 4,500

flying operational hours. It dropped 78,100 lbs. of bombs and depth

charges. The most significant statistic however, was nine successful attacks on

U-boats. Beside attacking enemy in French ports, the 304 also took part in a

great attack on Bremen. Its casualties were 24 missing, killed or

drowned.

The beginning of the 1943 looked promising: the Coastal

Command began cooperation with several Royal navy ships equipped with powerful

radiolocation stations, which vectored aircraft on enemy’s ships or fighters.

Allies started to gain an upper hand in the Battle of Atlantic.

For the 304 particularly, these better times

materialized on January 5, when Wellington E304 attacked a pack of U-boats at

45N/09W. They displayed a new tactic: when attacked, U-boats concentrated their

strong AA fire rather then diving away. It is believed that Poles did some

damaged to one U-boat during that attack.

But the number of sorties by the squadron slumped in

January as a bad weather set in. Only few days in that month were suitable for

patrols. In February conditions improved and pilots saw more flying. They also

saw more German aircraft.

Both sides showed fierce determination on February 9,

when S/Ldr Ladro’s (DFC) Wellington NZ-W was jumped by four Ju-88s. This

engagement was widely reported as an example of Allies’ cooperation. Read

more.

On March 26, the crew of F/O Skwierczynski surprised

surfaced U-boat and damaged it with depth charges. Two days later, similar

result achieved F/O Kolodziejski, although it is probable that the U-boat

(U-321) was sunk.

On the March 30 the Coastal Command Headquarters detailed off No. 304

Squadron to a new type of operations. The unit was relocated to Docking in

Norfolk as a part of 16 Group and reequipped with Wellington Mk Xs. On the day

of departure the CO received following telegram from AOC No. 19 Group Air

Vice-Marshal Bromet:

“I

just want to tell you how very sorry I am to be losing No. 304 Squadron. From

the moment the Squadron arrived in my Group all ranks got down to their new role

with a thoroughness and an enthusiastic spirit, which not only did them great

credit, but was most helpful to me and my staff.

I am very disappointed at having to part with such a

good Squadron, and the measure of this loss can be gauged by their record on

anti-submarine operations during the past year. Unfortunately, however, your

Squadron is wanted elsewhere for another type of work. Perhaps the change of

environment and the role will be agreeable - I hope it will - and, in any case,

I am sure the Squadron’s fine record will be maintained, and that they will

continue to be a thorn in the side of the Hun.”

S-304 (HZ258) Wellington Mk. X in 1943.

At Docking, to their dismay, Poles learned that now they became... a

torpedo squadron. New Wellingtons had more powerful engines but all the same

were to slow to be effective torpedo bombers. Generally, the crews accepted

their fate in the line of duty, but there were very few who were indifferent.

The living conditions at Docking were comfortable and food was excellent, a most

unusual thing in Coastal Command.

Conversion was done smoothly and quickly, but the

personnel were scattered all over to attend special courses: low-level torpedo

attack for pilots, special radar techniques for radio operators, refreshing ones

for gunners and navigators, or torpedo maintenance and handling for ground crew.

Soon after, it was realized that torpedoing

Wellingtons would be seating ducks for German gunners. The whole thing was

called off before the lesson would be learnt in reality of appalling losses.

Thus, after two month at RAF Docking - most of which was spent on very intensive

training – No. 304 Squadron was transferred back to 19 Group to resume

anti-submarine patrolling over the Bay of Biscay.

RAF Docking 1943. Squadron's Wellington Mk. X.

On June 10, the unit arrived at

Davidstow Moor in Corwall. The palce wasn’t very fortunate for aerodrome. It

had concrete runways, but wire netting was necessary to prevent aircraft

from sinking in mud and swamp.

It was located some 1000 feet above the sea

- thus frequented by rain-clouds - and bouunded rocky coast on west and

depression on east. Nissen hats completed the landscape.

There, the squadron received new Wellingtons Mk. XIII,

equipped with latest version of radar apparatus for detecting enemy

submarines and specially adapted for service in Coastal Command. One aircraft

had a prototype kit installed to detect submerged U-boat. These planes were

painted white. Additional equipment was very strong searchlight to illuminate

targets at night. Everybody’s guess was that the unit would operate at night

as well. The crews welcomed the first operational sorties, and the whole unit

seemed revitalized.

Some things had changed over the Bay of Biscay during

these two months. Enemy fighters were as active and dangerous as before, but

more numerous. After the fall of Tunisia, large force of the Luftwaffe was

relocated to Europe and big chunk of it joined the Battle of Atlantic. There was

a lot of work for Poles and they applied themselves to it with great zeal.

The area of operation became a scene of some savage

fighting and the 304 received its share of blows. In quick succession the

squadron lost several crews – its aircraft were shot down on: July 3rd,

July26th, August 13th and 22nd. The last lost was very popular crew of P/O

Porebski. They R/T only one short message: “AO- attacked by enemy fighters”.

Few more planes were written off after coming badly mauled and crashing near or

on the airfield. Only one U-boat was detected (August 1st) but got away before

NZ aircraft had a chance to attack it. Crews flew individually patrolling their

sectors and had much more chance to meet enemy fighters than its ships. The same

time Allies shipping losses in the middle of the Atlantic were staggering.

Finally the 304 got the break on September 5th. At the base a S.O.S.

signal came from NZ-M of F/Sgt Rybarczyk. Another loss seemed to be certain.

Then more signals came and it was learnt that the plane is limping back home.

Eventually, whole crew safe and without scratch landed at Davidstow

Moor but in aircraft which looked like sieve. Read more.

Later that month, operational flights were suspended

as the squadron was rearmed yet again. New radar devices were introduced along

with new tactics – more courses to attend. Some crews were sent to RAF Angle

for special school of low-level anti-submarine night patrols.

Then new aircraft came: Wellingtons Mk. XIVs carrying

a Leigh Light and powered by improved Hercules engines.

This aircraft was filled with electrical equipment and batteries and it

was difficult to navigate around it. It was heavily overloaded and when

throttled down it doped like a stone. Its speed was inferior to its predecessor.

Overall, it gave Allies a tactical advantage depriving U-boats from the cover of

night.

Wellington GRMk. XIV in service with No. 304.

Visible bulging under the rear fuselage is a retracted Leigh Light. Under the

nose it carried a ASV radar. This version had a single forward firing gun in the

nose.

Around the same time, W/Cdr Korbut became a new CO. He was determined to

perfect the crews in every aspect of tactics, both enemy’s and Command’s,

complicated equipment and night flying. He soon had full complement of 24 fully

trained crews.

On December 13th, as a

newly semi-reformed squadron, the 304 was transferred to RAF Predannack. Till

the end of the 1943, squadron did not record any successes but made itself

noticeable in the vast theatre of the Western Approaches. On Christmas Day, NZ

aircraft spotted a formation of enemy ships. The first one to see them was W/Cdr

Korbut, who was flaying as a navigator. Four days later, AOC of the 19 Group

sent following signal to W/Cdr Korbut:

“As a result of operations during the past few

days one valuable enemy blockade runner was sunk and two Narvik and one Elbing

destroyers were sunk and others damaged by H.M. ships, who only suffered

superficial damage and eight casualties. This highly successful operation was

largely made possible by consistent accuracy of position given in sighting

reports, and the excellent procedure in shadowing and bombing. Well done, all

aircrews and maintenance personnel.”

Thus, for the No. 304 Squadron the year ended on a bright side. 1943 was

a bad year for the unit. It had a long and bad spell of ill fortune. It lost

many crews, number of which exceeded significantly the number of U-boat

sightings or kills it had to its credit. The squadron made six attacks on German

sub boats, probably sinking one. It totaled 574 operational sorties for 4,770

hours.

With the

New Year the luck had turned. The weather was passable and several patrols were

flown. On January 2, Wellington “T” navigated by F/O Salewicz detected and

illuminated emerged U-boat. The attack with depth charges probably damaged the

raider. Two days B-304 achieved very similar success. The U-629 was damaged and

forced to abort its mission.

The crews led with skillful hand of W/Cdr Korbut started to

feel confident in their work. During long patrols they did not have to worry

about German fighters and new tactics proved to be working. Then, the bad

weather closed in and the normal flying was suspended for three weeks. Soon

after came bigger success. On January 28, the Wellington G-304 of W/O Buczylko

attacked U-boat in the Channel, and the crew claimed it a kill. Read more.

On the same night Wellington piloted by F/Sgt Matiaszek picked a fight with

Me-110 fighter, which resulted with slight damaged to both planes.

This was a happy and the most exciting period in the squadron’s

history. Nearly every day was eventful. During

a night patrol on January 31, the crew of F/O Konski attacked German destroyer.

The ship was depth-charged and strafed. Throughout January, 304 flew 78 patrols.

In February weather was better and there was more encounters with the enemy.

On the night of 3/4 February, Wellington of F/O Mielecki

successfully evaded attacks by two Ju-88s, and came home with slightly wounded

rear gunner P/O Miedziak. On February 11, B-304 piloted by P/O Czyzun damaged a

U-boat. Next night, Wellington “C” of Sgt Kieltyka attacked another one.

On February 19, the unit was transferred to Chivenor near Barnstaple in

North Devon. The aircraft took off for patrols from Predannack and landed at

Chivenor. Motor transport was already there. Thus, the move did not affected

operational flying.

One more probable kill happened on March 4, when the crew of

S/Ldr Werakso on “U” depth-charged emerged U-boat. The Admiralty considered

this ship sunk, but no proof was ever found.

The efforts made by 304 personnel in February was

noticed and on March 6th, following signal was sent to it from AOC No. 19 Group:

“I shall be grateful if you will convey to the O.C. No.

304 (Polish) Squadron my congratulations on the effort put up by the Squadron

during February. I understand that this Squadron has flown 110 sorties out of a

task of 115 and 1,074 hours out of a task total of 1,150. This is very

creditable in view of the fact that during the month of February the Squadron

moved from Predannack to Chivenor, while, in addition, February is a short

month. This speaks very well for the enthusiasm and hard work of all ranks, and

it is deserving of recommendation.”

Even though the March weather conditions were generally poor, the

squadron made 119 sorties. On many nights severe icing forced aircraft to return

to base, often in very dangerous conditions. On one of such nights, the Group

ordered all the patrolling aircraft back to bases and unaware stirred a

competition. Two aircraft, one from No. 407 (Canadian) and one from No. 304 took

off almost at the same time, and now neither wanted to touch down first. Each

pilot waited for the other to clear off. They flew all night and the match ended

only when both had empty tanks.

Slowly

the Battle of the Atlantic was dying down, and the enemy encounters were much

less frequent. Strong winds made sees rough which in return caused radar

impulses to deflect into greenish jumble on the screens. It became impossible to

find U-boats, which in fact were sailing through the Bay of Biscay in far lesser

numbers. In one isolated case, Wellington A-304 sighted a U-boat on March 10. It

was too late to attack.

On the night of March

25/26 an incident took place when one Polish crew attacked British ships,

fortunately not causing any casualties or damage. The crew was not informed

about the British presence in its sector. On the next night F-304 scrapped with

two Me-110s. F/O Czyzun flown perfectly, crouching as near the waves as possible

and the rear gunner, Sgt Baranski, shot down one of the attackers. Consequently,

he was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal. One of the crew, Sgt Czerpak

recalled:

“About two hours after we took off for a night patrol the rear

gunner broke the silence by remarking in a very casual voice: ‘Navigator,

you’d better fix the position-there are two Jerries on our tail.’ It was a

clear night and visibility was good, so we knew there was nothing for it but to

fight.

'Approaching to attack,’ the gunner drawled his next

report. ‘I’m going to give a burst.’ They must have been old hands,

because they came very close before opening fire. We tried evasive action. Steep

down to starboard did not shake them off, but it gave the rear gunner a chance

to throw some confetti. His aiming must have been as confident as his voice, for

when one of the Jerries swung under our tail it had a long trail of smoke mixed

with huge tongues of flame; a second later, there was an explosion on the

surface of the sea-a terrific flash which made the cockpit as light as day. The

other fighter continued to attack, but with less and less determination-and he

finally broke off.

The skipper checked each member of the crew by inter-coin.,

and everybody reported ‘O.K.’ But, a few minutes later, the rear gunner was

due to relieve the wireless operator, and he then said: ‘Sorry, my right hand

is none too sure.’ His face was covered with blood and his hand was bleeding

badly from a deep gash.

When we touched down at base more damage was found than had

been expected. There were a lot of holes in the port wing, and the rear turret Perspex

had been smashed to pieces by splinters. But it was only on the following

morning that we realized the full extent of our luck. The ground staff found

four armor-piercing bullets in one of the petrol tanks.”

The scene for continent invasion was begun to shape up and the Allies’

advantage was becoming clearer. People on both sides sensed the imminent end.

Germans introduced numerous new devices and weapons trying to invert the course

of war. One of them was Schnorkel, which enabled the U-boats to recharge

their batteries without losing way and when submerged at periscope depth.

Another new device installed on U-boats was a search detector, which gave

warning when airborne radar was scanning the sea in the vicinity. U-boats’

speed and range were also improved.

In the beginning of

April, Poles also received a novel apparatus: ASV Mk.VI-A. This model enabled

crews to find even snorkeling Germans. However, no new successes were recorded.

Wellington Mk. XIV in May 1944.

W/Cdr Korbut was replaced on April 10. The new CO became W/Cdr Kranc. On

this occasion, few high-ranking Polish officers came to Chivenor. Among them,

was W/Cdr Poziomek AOC of Polish Air Force Headquarters and former Co of No.

304. During the farewell party he volunteered for an operational sortie, and the

next day he flew as an extra on Wellington piloted by S/Ldr Stanczuk. This

aircraft was shot down by German fighters and whole crew perished.

Memorable

flight had a crew of F/O Ochalski on April 20. During its night patrol it was

they were attacked by two Ju-88. Polish Welligton successfully evaded many

German passes. This duel lasted for 1 hr 45 min. In the end, nobody got wounded

and although the aircraft suffered multiple hits, the crew brought it back

safely.

On 28th, W-304 of F/Lt Miedzybrocki detected and

attacked a U-boat, but the results of its action were unknown. In April the

squadron totaled 60 operational sorties. However, much more flying was done

since the several new crews were trained bringing the unit to its peak form.

May

came and the pre-invasion excitement grew.

U-boats presence near the French coast became somewhat more noticeable.

On May 5, N-304 of F/Lt Miedzybrocki detected two surfaced U-boats and was

greeted with fierce fire. Poles managed to attack and damage of them, although

aircraft was badly shot-up and had an onboard fire. On May 19, W/O Kieltyka

attacked surfaced U-boat caught with Leigh Light, but was forced to withdraw by

German fighter. In May the squadron’s crews flew 64 ops.

With the D-Day approaching, the squadron suspended all the operations,

and the crews were to have real rest. Intensive training, which filled last days

of May, stopped nearly completely. Not a single smoke bomb was dropped at the

wooden target in the middle of Croyde Bay. During the first days of June rumor

spread that no passes would be issued. Throughout the unit excitement grew, as

everybody hoped the imminent invasion would bring them close to their beloved

Poland.

Once it started however, there was nothing to do for

the Poles of No. 304. The unit was at stand-by, waiting for hordes of U-boats to

appear in the Channel. None was sited there. Allies air cover over Normandy was

overwhelming and the invasion proceeded better than expected. At Chivenor it was

learnt, that the Coastal Command would continue its offensive against

Doenitz’s submariners, started in the middle of May. U-boat forces gathered in

French ports stayed put for nearly fortnight before entering the most important

theatre of war.

June became even more memorable when on the 18th, the

crew of F/O Antoniewicz sunk U-444. Read more.

Three days later A-304 of Sgt Micel attacked and damaged another U-boat in the

Channel. Then, more crews made a score sheet. On July 6, E-304 detected and

depth-charged a submarine. Q-304 found its target on 14th and Y-304 on 25th.

This span of five weeks became the most successful period of time in the

unit’s history.

In the second half of 1944, the Battle of Atlantic was

practically won. U-boats force retreated to bases in Norway and Germany. Still.

The considerate number of them operated in Atlantic, but they were much cautious

and generally ineffective. In such

circumstances in August, the squadron amassed the biggest number of monthly

flying hours: 1,165 for total of 120 operational sorties. No enemy encounters

were recorded.

As the situation changed, Allies shifted its forces

near the North Sea to pursuit U-boat force there. As a result, No. 304 Squadron

was transferred to No. 15 Group and moved to RAF Benbecula

in the Outer Hebrides.

The new base presented itself to the Poles as a picture of misery in the

middle of the ocean. Located on a small, bare island, the base was a total

contrast to the sunny and comfortable Chivenor. Even those that remembered Tiree

shuddered with horror. Most in the squadron treated as a joke warning given them

at Chivenor: ‘When you’re on Benbecula don’t worry if you find yourself

talking to the sheep, but as soon as the sheep start answering back - look

out.’ Poles were greeted by a bunch of bearded characters who still flew

Swordfishes, and who quickly pointed out that the 304 predecessor, American

squadron of Fortresses, had been transferred on compassionate grounds.

Nevertheless, Poles installed themselves quickly and resumed operational flying.

Although for the rest of the year weather conditions

were regularly adverse, the unit did excellent job and totaled 276 patrols. Only

once, on November 23, the U-boat was sited but crash-dived leaving no chance for

an attack.

The

squadron’s overall record for 1944 was impressive. It chalked up: 1,010

sorties for 9,295 hours, six sightings, and 14 attacks on enemy

submarines.

The beginning of 1945 was marked with change of the

squadron’s commander. Starting from January 3, this duty was taken over by

W/Cdr Zurek, assisted by S/Ldr Pilniak and S/Ldr Krzepisz, commanders of Flight

“A” and “B” respectively. Together with new the commander came dreadful

weather with gales and severe icing conditions. Very little flying was done in

the first half of the month. As U-boats became more active, some patrols brought

little excitement but no successes: Wellington of W/Cdr Zurek attacked without

results a U-boat on January 12, and the crew of F/Lt Glowacki had similar

encounter the following night. Foul weather prevailed and take-offs of fully

loaded aircraft became extremely dangerous. Some of them were flown to other

airfields (Tiree or Limavady and Ballykelly in Northern Ireland), which had

better runways. From these airfields Poles flew fruitless escorts to Allies

convoys apart from carrying out its normal

anti-submarine patrols. Damned Schnorkel worked.

The luck had turned in February, when three crews

recorded attacks on U-boats:

- Wellington S-304 of W/O Marczak depth-chharged enemy on the Irish Sea on 2nd.

- The crew of F/Lt Wozniak on Wellington QQ-304 probably damaged one U-boat on

16th.

- Without results, Wellington E-304 of F/OO Ejbich assaulted another one on 20th.

Almost as an award for good service, came the news that the 304 would

move back to Cornwall. The personnel had quite enough of this sub-arctic

weather, and the prospect of moving to new base in South lifted crews’

spirits.

On March 5th, the unit was officially moved to No. 19

Group, and settled in RAF St. Eval. On its departure, the 304 received following

signal from Air Officer Commanding No. 15 Group, Coastal Command:

“Please

convey to W/Cdr Zurek and all ranks 304 Squadron my thanks and deep appreciation

of their sterling work whilst at Benbecula. That they mastered the North

Atlantic in winter is indicative of the high operational skill of the aircrews,

and that they produced the full quota of sorties under planned maintenance in

the very severe winter conditions prevailing revealed great keenness and

efficiency by the ground crews. A fine Squadron, and I wish you all the best of

luck and good hunting in this final phase of the European war.”

Also, Air Commander N. A. Pritchett wrote in the squadron’s diary on the

occasion:

“They fly when sea-gulls won’t.”

Soon

after installing itself in St. Eval – and taking quite a pleasure in doing so

- the 304 resumed its normal duty: huntingg for U-boats. But these were hard to

coma by. During March, April and first week of May, Poles flew 202 unrewarding

sorties. Victory was imminent, but the intensity of flying did not slacken.

Still the squadron was proceeding in training with various new apparatus, which

enable the crews to detect snorkeling submarines.

On April 2nd, a large U-boat identified after the war

as the U-321, was found and damaged by Wellington Y-304. The attack took place

at 500 00’ N-120 57’ W. On April 22nd, the

squadron’s last U-boat sighting was recorded.

On May 4th, Doenitz ordered the remaining U-boats

forces to cease theirs activities and return to bases. On 7th, they were obliged

to surrender. One of those was captured by Polish Wellington of No. 304

Squadron, on May 11th. The squadron’s last operational sortie was flown on May

30, 1945, and its service within Coastal Command was terminated on June 14, when

it was transferred to transport duties.

In August, the 304 was reequipped with Vickers Warwick

Mk. I and Mk. III, and in January 1946 with Handley page Halifax Mk. VIII.

Squadron's code letters were change to "PD". With

the Transport Command, Poles crews flew mostly linking England with Italy and

Greece. Disillusioned with the outcome of the war and not having their free

country to return to, they welcomed the opportunity to various undertakings to

secure a little bit they future somewhere where they would be less unwelcome.

The

unit was disbanded in December of 1946.

No.

304 (Polish) SQUADRON operational summary:

| Bomber

Command: |

488

operational sorties for a total of 2481 hrs.

Total bomb load: 800 tons. 12 a/c lost. 102 airmen KIA

or MIA, and 35

POW. |

| Coastal

Command: |

2,451

operational sorties for a total of 21,331 hrs.

21 ton of bombs and 43 tons of mine dropped. 19 a/c lost. 106 airmen KIA

or MIA. Total of 31 U-boat attacked: 2 sunk, 5 damaged. 16

attacks with results unknown or unconfirmed. Crews credited with 3 enemy

a/c shot down , 3 probable and 4 damaged. |

|