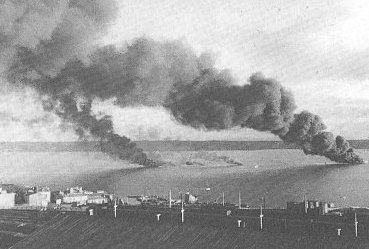

Scuttled ships in the Rade de Brest

Shipwrecks

diving into history

Operation Aerial

The story of “Operation Dynamo”— the evacuation of Allied troops from Dunkirk — is as well known as any episode of the Second World War. During the week starting at 1857 hrs on the 26th May 338 226 Allied troops were transported to England while bombs from General Baron von Richtofen’s Stukas rained down upon them (he was the cousin of the famous World War One ace Baron Manfred von Richtofen - "The Red Baron"). What many don’t know is that after this operation there were still thousands of Allied soldiers and airmen left in rapidly falling France.

Scuttled ships in the Rade de Brest

In England, on Saturday 15th June 1940, the decision was made to launch the evacuation of any Allied troops remaining in France - following "Operation Dynamo" - from the western French ports. Code named "Operation Aerial", the task of lifting the troops was given in large part to the British Merchant Navy fleet and escaping French ships. Saint-Malo, Brest, Sainte-Nazaire and La Pallice were designated as the major points of evacuation, but in practice any harbour was used.

Under the command of General

Charbonneau, rearguard French troops began manning two barely prepared defence

lines around the crucial harbour of Brest -

the first in a 30-kilometre arc, the second between 12 and 15 kilometres from

the city centre. On 17th June Maréchal

Pétain, who had taken over as new President of France after the resignation of

Reynard and opened negotiations for armistice terms with the German high

command, made a radio appeal to French troops to lay down their arms. France’s

World War One “Hero of Verdun” saw the end of his country’s fight against

the Germans as inevitable, and the death of more men to prolong this unavoidable

event unnecessary.

While Allied rearguard

units that had retreated all the way from Belgium, assisted by personnel from

the destroyer H.M.S. Broke, were

destroying their land locked equipment and any harbour facilities that could be

of use to the German invaders. British

Naval officers had already landed at the ports to oversee the evacuation

operation, and by Monday 17th June most troops not engaged in battle had been

taken off. From Brest alone 28 145 British and 4 439 Allied personnel -

including French, Poles and Canadians -

were ferried to England by the morning of 18th June 1940. Although undoubtedly

under threat from the German advance, French military commanders were - unfairly

- unimpressed with the haste that the BBritish “fled” from Brittany. The need

for a scapegoat to carry the humiliating defeat of France's vaunted army tainted

thinking at the time ...and after. As the last British soldiers commanded by

Colonel W.B. Mackie were leaving Brest, the German panzer troops were however

still 180 miles away, exhausted with the pace of their own advance.

Throughout, the incessant Luftwaffe mine-laying raids continued, creating problems of port access until swept by the overtaxed French minesweepers. In the port itself, the job of loading and evacuating 900 tons of gold bullion from the Bank of France had finally been completed and the vessels charged with this precious cargo sailed for the safety of Canada and North Africa. Once this task was complete, the French Admiralty issued the order for a final evacuation of Brest. Remaining stocks of petrol were set alight and an enormous pall of greasy black smoke tarnished the summer skies above the city.

During the afternoon of

18th June, Admiral de Laborde (French Naval Commander Western Theatre) ordered

the evacuation of all seaworthy vessels. A massive flotilla of more than 70

warships of all sizes, as well as 48 French and 28 foreign cargo ships, set sail

for either North Africa or England. Despite strenuous efforts from small French destroyers snapping

like terriers at the heels of the large cargo ships, there was confusion and

alarm as dozens of panicked skippers jammed through the narrow channel leading

from Brest to the sanctuary of open water (amazingly there were no casualties in

the stampede, the narrowest escape being for the 9 684 ton hospital ship Canada

when her propeller became entangled in a north channel marker buoy). All were filled to capacity with any remaining French and Allied

troops under the command of General Béthouart (recently returned, with his defeated soldiers, from the Allied expedition to

Norway). Béthouart demanded that priority be given to Polish troops and those

German and Italian men within the ranks of the Foreign Legion, so as to avoid

any possible retaliation against their families if captured by the Germans. They

were all taken safely to England.

That June evening marked

the departure from Brest of all of the port’s ships that would escape the grip

of German occupation. Several were left behind to be taken as spoils of war by

the German invaders. Two British ships -

the 3 554 ton cargo ship Dido and the smaller 279 ton Luffworth

among them. Both would fall under German control, Dido surviving until 1945 when she was sunk by enemy action, while

the latter was scuttled by the Germans at the war’s end, only to be refloated

and operated by her new French owners.

Only three ships were

lost at Brest as a result of enemy intervention on the 18th, all

three hitting magnetic mines laid by low-level Luftwaffe flights. The 4 499 ton

cargo ship Capitaine Maurice Eugene of

the Société “Les Cargos Algériens,

carrying holds full of wine, was holed by an explosion near Vandée reef.

Listing badly and with rising waters inside she was abandoned by her 39-crew and

sank. The tug Provençal also

vanished in the spume of a mine detonation, while the final loss of the day was

the only French naval vessel sunk -

the 850 ton "Amiens" class sloop Vauquois.

With the dawn of Wednesday 19th June 1940, the day following the sinking of the Vauquois, German troops occupied Crozon and the surrounding regions. The first German troops entered Brest at 2130 hours, and immediately began disarming the remaining scattered French troops. As if to mirror the sunken fortunes of this port city there was one final casualty. At 2230 hrs a 522-ton, 40 year old, twin-screw steamer belonging to the Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer was sighted at anchor in Camaret Bay by advancing German troops. Sighting their artillery on her slim hull they opened fire, hitting squarely the forward hold.

Despite fighting between

German and French troops near Landivisau, Wehrmacht officers demanded by

telephone that the Military Governor of Brest order a cease fire or risk the

bombing of his city by 100 aircraft, and attack from three armoured divisions.

After consultation with the two highest-ranking French infantry commanders -

General Picard-Claudel and General Charbonneau -

Military Governor, Vice Admiral Traub, bowed to the inevitable and surrendered

Brittany to the Wehrmacht, the cease-fire to take effect at 1900 hrs on the

north coast and 2030 hrs to the south. The next day, in the name of the

Kriegsmarine, the German Konteadmiral Lothar von

Arnauld de la Perière took command of the Brest Arsenal as the Marbef Bretagne

(Marine Commander Brittany). The French officer that he named responsible for

any French personnel remaining as part of the armistice agreement was Capitaine

de Vaisseau Le Normand.

Brittany’s other main ports had endured similar scenes to those in Brest. At Lorient on 18th June 1940, a total of fifteen warships and thirty-five smaller vessels left the harbour. Only a single vessel was lost to enemy action. The large trawler La Tanche struck a German mine and sank near to the Truies buoy marking the entrance to Lorient. She was carrying nearly 200 people as well as a 30-man crew. Among her passengers were Polish soldiers, French airmen, mechanic apprentices and several of the French sailors’ wives and children. The explosion was so violent that she sank in seconds and only twelve people were rescued. The port was declared an open city and surrendered by Admiral de Penfenteny on the 21st June.

Despite this tragic incident, and those at Brest, losses could have been much worse. The Luftwaffe was having trouble reaching these two ports, their operational airfields being some distance away. Saint-Nazaire, resting alongside the Loire River, was to witness the most devastating sinking of the evacuation when German KG 30 Dornier Do 17 aircraft bombed and sank the Cunard Liner Lancastria, crowded with British soldiers.

The exact number of dead

has never been established, but it is known that at least 3,050 people were

killed. Today the latest estimated figures state that there were actually more

than 7,000 men aboard, and 4,500 to 5,000 dead. Even without this revised death

toll the horrifying statistic of people killed during the sinking gave the Lancastria

the unwanted title of worst merchant loss for the British during World War

Two, and the fourth largest casualty figure of any single maritime sinking.

After the horrendous sinking of the Lancastria

Captain Sharp, her commander, was taken back to England with other survivors.

Briefly in command of the Antonia, he

was transferred to command another Cunard vessel — the Laconia.

This 19,695 ton ship was to play an important and tragic part in the course of

U-boat warfare, after its torpedoing by U156,

under the command of Kapitänleutnant Hartenstein,

on 12th September, 1942. Captain R. Sharp,

who had lived through the most costly Merchant Navy loss of the Second World War

— the Lancastria — did not

survive the sinking of the Laconia,

the death toll of which made it the second most costly British maritime loss of

the war.