I am fresh from the beautiful damp woods, with all their wealth of budding green and tender flowers, and, absurd as it seems to try and tell you about them, I really can't help it. When did it ever seem as if there had been another springtime, or as if a violet or a windflower had been seen before? The glory of it all makes me almost afraid, and it seems such a pity ever to come home from such an exquisite fairy-land.

Aunt Anna and I had planned a walk when I first came, but it has rained constantly; however, to-day we bid defiance to the rain, so it respected our bravery and our umbrellas, which we were punished by having to carry under our arms.

Such a depth and richness of green was brought out by the dampness that I would not have had it a dry day for the world, and indeed I must have been born with a spring in my mouth instead of a silver spoon, for I always feel twice myself in a showery ramble.

I wanted to go straight up the perpendicular bank behind Mrs. Brown's house, and Aunt Anna's enterprise at least equaled mine, and delicate mosses and lichens, in which were planted violets, housotonia and anemones, and new ferns undoubling their green fists, with polygalas, saxifrage, and, to my great joy, columbines. The last has always had a magical fascination for me, and makes me feel as no other flower can. It represents the aristocracy among wild flowers, with its haughty and airy grace and proud crimson and gold. It not only "the likeness of a kingly crown had on," but it is itself a crown.

There was a peculiar half moss, half lichen on the rocks, looking like large green ears, and with this I lined the bottom of my basket, intending to cover the earth in Aunt Anna's flower-pots with it. Then the flowers showered in, mixed with long trails of partridge-vine with its bright red berry. I pulled up a royal plant with all its nodding columbines by the roots to put down by that huge stump in the garden, where the simple thing doesn't know but it is at home. Then we penetrated into the delicious woods, wishing for you....at every step. Oh, why aren't you here? I can't bear to enjoy it all without you, when you want it so much; and should we not find beautiful secrets together in these deep recesses?

The trees were mostly tall, slender pines, many of them thrusting their twisted roots out of the ground, and others fallen all their length, making bridges and arches, and holding up a huge shield of roots at the end. The busy moss had wrapped them all in its soft green, and had lined and draped a thousand green recesses, making me wish I was a fairy to live in them. Surely, man has never built a mansion that is arrayed like one of these!

It was a most Gothic wood, with its pointed trees and arches, and long vistas inviting us onward. How impossible it seems that a wood path can ever have an end!

At last we saw water gleaming at a distance, and came to a clear tarn, lined with brown leaves and holding a fair picture in its bosom. A short distance from this was a cavernous spring that delighted me extremely. The opening was oblong, lined with the natural rock and stones for a depth of some five feet, and then it was excavated under the earth, or rather the rock, and there we saw the water bubbling, clear and cold. What a place for summer, and how one envies the frogs! But these seemingly endless woods had an end, and we came out on some open rising ground, whence we had a glorious view of the valley, where the trees were already dreaming of summer, and sketching an outline of their greenness.

Luminous mists, "slow-dropping veils of thinnest lawn," took the place of the sunshine, making a pearly radiance in the air, and the far blue mountains made an exquisite horizon.

And here the world came upon us, in the shape of two small children�a girl with some columbines in her hand, and a boy with some plebeian dandelions. "I say, you give me some of yours," said the boy, "and you shall have all of mine!" "No, I don't want yours," said the girl, airily skipping down the bank. "Oh, you're stingy!" said the boy, as he followed her, with an accent of the most supreme contempt.

Then we came home, and I think you might wish yourself either one of your pictures if you want to have a good time. Before one (picture) is a little basket, lined with moss and filled with tiny ferns, violets, anemones, housotonias, and polygalas, with many more. Under the other is a tall vase with a long partridge-vine twisted round it, and filled with columbines, uvularias, and slender branches of delicately tinted maple leaves mixed with white flowers and ferns. I enjoyed arranging them very much, but oh how dead and colorless my letter seems. How I wish I had a little bit of the secret of nature to put into it! But that secret hovers near me in the air, it vanishes among the leaves and whispers in the flower bells, and though I cannot grasp or utter it, I feel as if in time it might make me beautiful with its peace.

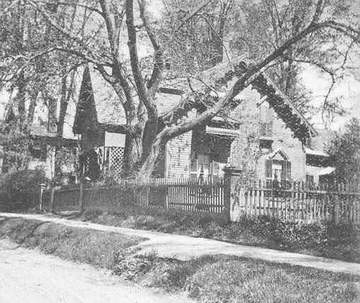

Una Hawthorne Visited the Higginson Family in This Cottage

on Asylum Street in 1868

" . . . She was excessively fascinating; her father's description of her looks is perfectly appropriate; sometimes she seemed beautiful then entirely the

Una Hawthorne, the eldest child of Nathaniel, was

engaged in 1867 to Storrow Higginson, a nephew to Thomas

Wentworth Higginson.

[Samuel Storrow Higginson b. March 22, 1841, at Cambridge, Massachusetts, son of Stephen; studied with Henry David Thoreau; wrote funeral tribute to Thoreau printed in the Harvard Magazine; assembled Charles C. Frost's herbarium for natural science room of Brooks Memorial Library 1891.]

Una in this letter records following exactly in the footsteps of Thoreau during his botanizing visit to Brattleboro in 1856. She may have been doing this at Storrow's request.

Una at this time probably also visited the graves of Edward Palmer, Mary Palmer, and Royall Tyler in Prospect Cemetery. It is likely that she understood that Judge Royall Tyler was the model for the criminal Judge Jaffrey Pyncheon in her father's romance, The House of the Seven Gables (1851), and that when Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote the secret story of Clifford's drowning for The House of the Seven Gables, he combined two stories from the Palmer family--that of the leap of Joseph P. Palmer from the bridge in Vermont to his death, and that of the drowning of Edward Palmer in the Connecticut River at Brattleboro, Vermont.

-

Nathaniel Hawthorne: Studies in The House of the Seven Gables

- Hepzibah Pyncheon's Witchcraft Execution

- Clifford Pyncheon's Suicide

- Sophia Peabody and the Legend of the Sleeping Beauty

- Hawthorne and Melville

- Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft in "Rappaccini's Daughter"

- Judge Royall Tyler

- The Drowning of Edward Palmer

- Una Hawthorne in Brown's Woods, Brattleboro, Vermont