THE FOUNDING OF GEORGIA

The establishment of the Restoration proprietary colonies expanded English settlement along the length of the Atlantic coast from New England to South Carolina. Although the population of each colony continued to grow, pushing the frontier of settlement steadily westward, for several decades there were no attempts to enlarge the English realm in America farther north or south. Not until 1733 did another new colony emerge: Georgia, the last English colony on the mainland of what would become the United States.

Georgia was unique in its origins. It was founded neither by a corporation (as Massachusetts and Virginia had been) nor by a wealthy proprietor (as in the case of Maryland, the Carolinas, Pennsylvania, and others). Its guiding purpose was neither the pursuit of profit nor the desire for a religious refuge. Instead, Georgia emerged from the work of a group of unpaid trustees. And while its founders were not uninterested in economic success, their primary motives were military and philanthropic. They wanted to erect a military barrier against the Spaniards on the southern border of English America; and they wanted to provide a refuge for impoverished Englishmen, a place where men and women without prospects at home could come and begin a new life.

The need for a military buffer between South Carolina and the Spanish settlements in Florida was growing urgent in the first years of the eighteenth century. There had been tensions between the English and the Spanish ever since the first settlement at Jamestown; and although in a treaty of 1676, Spain had recognized England's title to lands already occupied by Englishmen, conflict between the two colonizing powers continued. In 1686, Spanish forces from Florida attacked and destroyed an outlying South Carolina settlement south of the treaty line. And when Spain and England resumed their war in Europe in 1701, hostilities erupted in America again. The war ended in 1713, but another European conflict with repercussions for the New World was continually expected.

General James Oglethorpe, a hero of the late war with Spain, was therefore keenly aware of the military advantages of an English colony south of the Carolinas. Yet his interest in settlement rested even more on his philanthropic interests. As head of a parliamentary committee investigating English prisons, he had grown appalled by the plight of honest debtors rotting in confinement. Such prisoners, and other poor Englishmen in danger of succumbing to a similar fate, he could, he believed, become the farmer-soldier of the new colony in America.

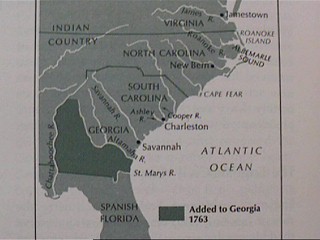

A 1732 charter from King George II transferred the land between the Savannah and Altamaha rivers to the administration of Oglethorpe and his fellow trustees for a period of twenty-one years. In their colonization policies they were to keep in mind the needs of military security. Landholdings were limited in size so as to make settlement compact. Blacks--free or slave--and Roman Catholics were excluded to forestall the danger of wartime insurrection and of collusion with enemy coreligionists. And the Indian trade was strictly regulated, with rum prohibited, to lessen the risk of Indian complications.

Oglethorpe himself led the first expedition, building a fortified town at the mouth of the Altamaha. Only a few debtors were released from jail and sent to Georgia, but hundreds of needy tradesmen and artisans from England and Scotland and religious refugees from Switzerland and Germany were brought to the new colony at the expense of the trustees, who raised funds from charitable individuals as well as from Parliament. Though other settlers came at their own expense, immigrants were not attracted in large numbers during the early years. Newcomers generally preferred to settle in South Carolina, where there were no laws against big plantations, slaves, and rum. Before the twenty-one years of the trusteeship were up, these restrictions were repealed, and after 1750, Georgia developed along lines similar to those of South Carolina.

In 1763, the land south and west of the Altamaha River, east of the Chattahoochee River and north of Spanish Florida were added to Georgia.

SOURCE: A Survey of American History - Sixth Edition - By Richard N. Current, T. Harry Williams, Frank Freidel, Alan Brinkley