|

We, the Romani people, are united under one flag. The blue stands for the sky, green for the earth and red for the Indian wheel.

|

Word list in Romanes (Gypsy Language) with English meanings

V�solo dad�sko ges/dives= Happy father's day or bahtalo dadesko dives

But baxt thaj sastipe! Much luck and health! Chaches phenes! You are telling the truth! Lachipe thaj baxt tuke katar miri dai! Best regards to you from my mother! Te aves baxtalo tu thaj sari tiri familia! Luck to you and your whole family! Me mangav tuke baxt! I wish you the luck! Mishto sim! I am ok! Nais tuke vas lache nevi pena! Thank you for the good news! Lacho deves! Have a nice day! Baxtalo drom! Lucky way! Lacho rat! Have a good night! Si e kerdo! It is done! Parikerav tut vas tiro lacho ilo! Thank you for your kind heart! Gadje! Non Romani person Familia! Family Phral! Brother Phen! Sister Mishto avilan! Welcome Lacho deves! Good afternoon Liloro! Gypsy mail Miro anav! My name is... Ha tuke! To you Me kamav te khelav! I want to dance Sar mai san? How are you? So nevo? What's new? San tu Rom? Are you Gypsy? Me voliv tu! I love you Chi mai diklem ande viatsa! I never saw such a thing in my life! baxt, sastimus! Luck and health Dikes oda baro shero! Look at that show-off (Lovara dialect) Lavuta! Violin Si-ma dosta! I have enough Shai to gilabav thaj te khelav! Let's sing and dance Shai te hav thaj te piav! Let's eat and drink Lachi rat! Good night Tatcho! True

Ach mishto, stay well or stay cool Devla, vocative of Devel Dikes oda barn shero, Look at that show-off. Lovara dialect diklo (m. sing.), scarf, headscarf, handkerchief. diwano (m. sing.), meeting, discussion dopo (m. sing.), the axle of a car with one wheel mount sawn off which serves as a portable anvil among the Coppersmith Gypsies dukyaiya (m. pl.), stores; Lit. store fronts which serve as fortunetelling parlors for Gypsy women in North America. galbi (f. pl.), gold coins, usually worn around the neck on a chain Gazho si dilo, The non-Gypsy is a fool Gazhya (f. plur.), non-Gypsy women, plural of Gazhi Iwon nashentar, They are eloping too kai (adv.), where Kai e Tinka?, Where is Tinka? Kana, when Karalo, lustful Kon san tu? Who are you? Love, money Shave, sons, children Sinto, a man of the Sinti group of Gypsies Sinteza, a woman of the Sinti group of Gypsies Si-tu, have you Wortako, partner, friend or buddy

Che chorrobiya How odd! Che fyal Rrom san? What kind of Roma are you? Che vista san? What clan are you? Haide andre Come in! Kai zhan le ranya? Where do the ladies go? Kai zhas? Where are you going? Katar aves? From where do you come? Me bushov... My name is.... Mishto, nayis-tuke Fine, thank you Sar bushos tu? What's your name? Sar san? How are you? Si tut yag? Do you have a light? So mai kerdyan? What have you been up to? So mai keres? What are you up to? So nakhlo? What happened? So zhal? What's happening? Yertisar man Pardon me Bokhali sim I'm hungry

Hederlezi Sa e Rroma, Daye All the Roma, Mother E bakren chinena Are sacificing lambs Ame sam chorrorre We are very poor Dural beshava I live far away Sa e Rroma, Daye All the Roma, Mother Amaro baro dives Our holiday Amaro baro dives Our holiday Hederlezi Hederlezi Sa e Rroma, Daye All the Roma, Mother Sa e Rroma djilabena All the Roma are singing Sa e Rroma, Daye All the Roma, Mother E bakren chinen They are sacrificing lambs Ei... Hey.. O sa e Rroma, Bado Oh, all the Roma, Father Sa e Rroma, o daye, All the Roma, Mother O sa e Roma, Babo Oh, all the Roma, Father Ei, Hederlezi, Hederlezi Hey, Hederlezi, Hederlezi Sa e Rroma, Daye All the Roma, Mother Sa e Rroma khelena All the Roma are dancing Sa e Rroma djilabena All the Roma are singing Amaro baro dives Our Holiday Sa e Rroma, Daye All the Roma, Mother Sa e Rroma bashavena All the Roma are singing E bakren chinen They're sacrificing lambs Ei...Hey O sa e Rroma, Babo All the Roma, Father

|

|

Voliv Tut Ages 'I love you today' Voliv tut ages I love you today Voliv tut tehara I'll love you tomorrow Voliv tut nai but I'll love you much more Desar mai anglal Than ever before Khel, khel, khel thai gilaba Dance, dance,dance and sing Khel, khel, khel thai gilaba Dance, dance, dance and sing Av, av, av vesolo Be, be, be happy! Av, av, av vesolo Be, be, be happy! |

Pas o panori Near the water pas o panori near the water chajori romani sweet Romani girl me la igen kamav I love her very much joj mamo.joj mamo Hey Mother, hey Mother (m�mo is vocative and means oh mother) de mam pani mamo Give me water, mother, (should be de man, not de mam) de mam pani mamo ditto de mam pani give me water pas o panori beside the dear water beselas korkori She was sitting alone pre ma uzarelas She was cleansing me |

Dilaila Yoi Dilaila Katar woi phirel, lulugya bai baryon Katar woi chi phirel, lulugya bai kernyon Delaila, me gelem te sovav-man Pe lake chunga Zurales woi xoxadyas man Zurales woi xoxadyas man Woi shinyas murre bal Dililah Delilah, because of her sexy figure That resembles a Holy Icon Oh, Delilah From where she walks, flowers will surely bloom, From where she walks not, flowers will surely wither |

Desh-u-shtar-war dui Dui, dui, dui dui Desh-u-shtar-war dui Te chumidel. te chumidel parno mui �nda l�te me mer�va �nda l�te pharruv�va Yoi, D�le, nai nai nai isi m�nde chaiyorri �si m�nde, isi m�nde shukarni �nda l�te me mer�va �nda l�te pharruv�va Yoi, D�le, nai, nai, nai Ten times two Two, two, two, two, Ten times two Oh to kiss a an innocent mouth Because of her I am dying (I love her very much, idiomatic) Because of her I am falling apart Oh, Mother, nai, nai, nai I have a girl A beautiful girl A beautiful girl Because of her I am dying Because of her I am disintegrating Oh, Mother, nai, nai, nai. |

Check out these video links on Indian customs and history. Look out for the ceremony in the temple with the mother Goddess and the male God in the second link. Origins of civilization-INDIA-the empire of spirit 3/6 Origins of civilization-INDIA-the empire of spirit 5/6

|

Parvathi is Lord Siva's consort & like Lord Siva, she is portrayed in her roudra & serene aspects.In her serene aspect, she is depicted as Uma or Parvathi & is usually seen along with Siva & also their children Lord Ganesha & Lord Muruga. She is seen with only two hands, holding a blue lotus in her right hand. In her terrifying aspects, the most commonly worshipped forms are Durga & Kali. These are forms taken by the Goddess in an effort to destroy some form of evil & hence even these forms need not invoke fear, for she is the mother who has risen in anger only to destoy evil forces and provide eternal happiness and peace to her children.

|

Go to Yvonne's Historical Gypsy book website to get a free download of the book about her Romani grandmother's accounts of life in Germany through two world wars plus, you can also download other Romani literature to read. |

|

|

|

|

My 2 children, Tim and Eve, performing at a Ukrainian Romani show on 17\12\2006

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Karsi Sanat Galerisi Istiklil Caddesi Elhamra Pasaji No: 130B, Kat: 234430 Beyoglu Istanbul 5 Nisan 2007 17.30 - 19.30 Adrian Marsh, Researcher in Romani Studies, University of Greenwich, London |

|

Extracts from Canadian Gypsy writer and activist, Ronald Lee�s book, �The Gypsy Invasion.� (reproduced by kind permission of the author) These �black trains� were so-called by the Hungarians who compared them to the trains in the Republic of South Africa under Apartheid which brought in Africans from the shantytowns to do menial work in Johannesburg. Another, more accurate term was �Gypsy trains.� In Budapest, the visiting Romani workers were housed in government-run workers� hostels, the men in one and the women in another. Husband and wife were separated and could only meet outside the hostel. The Roma, hopefully, planned to work in Budapest or some other industrialised city for a few months and then, if married, the couple could return home to their children, who were being cared for by relatives. Single men or married men who went to the cities alone often spent all their earnings carousing on the weekends with one another to forget their loneliness and often returned home no better off than when they left. A so-called �Gypsy train� leaves from platform three of the station in Miscolc towards Encs, Hidasn�meti, in early afternoon. Not only poor people working in Miskole, but also those who work in Budapest, travel by this train. The train with second-class carriages only, is packed. Smoke and the smell of brandy blend in the air, (playing) cards clatter on caps, knees and ivy green leatherette seats. Some (Roma) sleep propped against the back of the seat, their heads tilted to one side, their fingers holding tight onto their cracked brief-cases. Those who are not satisfied with their wages, play �snobli� (a gambling game) as if they wanted to get rich from pennies. Winners make a gesture of resignation: �This is not even enough for the pub.� (an evening�s night out). Losers are helplessly quiet or start to quarrel and someone gets slapped in the face. (Tam�s-R�v�sz, 1977.221: Szuhay, P. & Barati, A. 1993, p.179) The Vayke (Brickmakers, Romungero Group) were forced to take the �Black Train� to Budapest to work as street sweepers and to perform other unskilled labour. Geza, who was a child, remained at home with his grandparents in order to go to school, where he was physically and verbally abused, insulted, beaten by teachers and fellow students and segregated in the classroom. He and the other Romani children were punished for speaking Romani, usually by a cuff on the ears followed by a verbal tirade about how Romani was not a real language, but a jargon used by savages who must now learn a civilised language and speak Hungarian. Geza�s classmates were allowed to call the Romani children �dirty Gypsies,� spit on them and beat them. After democracy arrived in 1990, the skinheads and neo-Nazis began persecuting the Roma. The Roma, who had been working under Communism, were now unemployed and every week, there was news of skinhead violence against Roma, most of which was never reported, or improperly reported as �brawls� rather than as assaults or beatings based on racism. Periodically, the Romani grapevine would report a murder or a rape which would never be reported as a racist crime against Roma. Murder and rape victims became anonymous �Hungarians� in the news stories. Romani shoplifters or pilferers of agricultural produce were reported to be part of a Cig�ny �crime wave� in the media. Geza and his wife were now living in slum housing and subsisting on menial work. Their district in Budapest was constantly raided by skinheads or neo-fascists who smashed windows, threw gasoline bombs, left Nazi slogans on the walls, physically, assaulted Romani men, physically and sexually assaulted Romani women and generally made the Roma live in a state of siege. When Geza went to look for work as a driver, his only qualified trade, he was always told the job was filled or that it wasn�t company policy to hire Cig�ny. Often, a Hungarian foreman would tell him: �Why don�t you Gypsies make bricks like you used to do and leave the jobs for Hungarians?� After Geza�s wife was assaulted by racists, they decided to seek Convention-refugee status in Canada. The story of Geza and his wife, with minor detail differences, is typical of hundreds of Hungarian-Romani refugees fleeing to Canada, many of whom also have evidence of physical abuse, beatings, rapes, sexual abuse or other atrocities as a result of skinhead, neo-fascist , police or mob violence against Roma. Physical violence, however, is the Nth degree of systemic discrimination, which is the cradle-to-the-grave lot of the Roma in Hungary. Since they obtained work permits, Geza and his wife, like the vast majority of Hungarian-Romani refugees, have been working at whatever jobs they were able to find in Canada. In the words of the song by Canadian artist Leonard Cohen: There�s a crack in everything, that�s how the light gets in. In the case of Hungary, there is a widening crack in the cosmetic fa�ade erected for the benefit of the EU and the exodus of Romani refugees to Canada and elsewhere, such as to Strasbourg, is letting in the light which it is hoped will expose the hypocrisy of the current Hungarian government and force it to do something concrete and positive towards ending the persecution and systemic discrimination to which the Roma are subjected in Hungary. |

Extract from 'The Concoctors' by Ian Hancock Romani Archives and Documentation Centre

The fact that some of these invented "facts" originate with Romanies themselves�and we may add Ray Buckland, Lee Fuhler and Patronella Cooper to the list (see bibliography) is distressing, since it gives the stamp of legitimacy to such misinformation and, when exposed, only reinforces the image of untrustworthiness we must live with. It also suggests that while these authors may indeed have one or more Romani forebears, that fact is only incidental to their real life, which clearly lacks any first-hand involvement with the day-to- day Romani world; they have accepted instead the `magical' pop- culture stereotype created by non-Romanies. If they are fully aware of what they are doing and are exploiting such misinformation solely for profit, then they do no credit to the people they claim to represent, and seriously hold back the Romani human rights effort.

|

Maria Theresia and Joseph II Policies of Assimilation in the Age of Enlightened Absolutism The Age of Enlightened Absolutism, was characterised by essential changes in the sovereign policies toward the "Gypsies". In the face of the complete failure of all attempts to banish them permanently from their dominion, the sovereigns of the Enlightenment were searching for new methods and ways to solve the "Gypsy problem" from the second half of the 18th century on. Therefore, assimilation by decree of the state was added to the methods of expulsion and persecution of the Roma that have been practiced to this day. Maria Theresia, the Empress of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, set an example with her policies of assimilation that influenced many other sovereigns. Striving to make the Roma settle down as "new citizens", or "new farmers", she issued altogether four great decrees during her reign (1740-1780). By means of these decrees the Roma would be forced to give up their ways of life. The first decree (1758) forced the "Gypsies" to sedentarise. They were denied the right to own horses and wagons in order to keep them from "nomadising". Furthermore, the Roma were issued land and seeds and became liable to pay tribute from their crops just like the other subjects of the crown. They were supposed to build houses and had to ask for permission and state an exact purpose if they wanted to leave their villages.In the next decree (1761) the term "Zigani", which was commonly used for the Roma at that time, was replaced by the terms "new citizen" (Hungarian: "Ujpolg�r"), "new farmer" (Hungarian: "Ujparasztok"), "new Hungarian" (Hungarian: "Ujmagyar") or "new settler" (Hungarian: "Ujlakosok" or Latin: "Neocolonus"). They were supposed to give up their old ways of life, together with their old name, in order to accelerate the process of integration. "Gypsy boys" would learn a trade or be recruited for military service at the age of sixteen if they were fit for service. In 1767 Maria Theresia had the jurisdiction withdrawn from the Voivods and all "Gypsies" became subject to the local jurisdiction (3rd decree). At the same time, they were ordered to register and - based on this registration - conscriptions were carried out for the first time. The fourth decree issued in 1773 prohibited marriages between Roma. Mixed marriages were encouraged by subsidies. The permission to get married, however, was bound to an attestation of "a proper way of life and knowledge of the Catholic religious doctrine". Since the Empress and her counselors were of the opinion that the "civilization" of the "Gypsies"was the basis for a successful "domiciliation", she ordered that all children over the age of five should be taken away from their parents and be handed over to a Hungarian farmer�s family who were supposed to take charge of their Christian upbringing against payment. The children should grow up isolated from their own parents in different comitats, go to school and later learn a trade or become farmers. Despite the sanctions ordered in case of offences, the coercive measures imposed by Maria Theresia and Joseph II were effective only to a certain degree. They only succeeded permanently in what is Burgenland today, where the Roma actually settled down and have stayed up to the present. A large number of Roma were successfully assimilated there: frequently children did not return to their own parents, stayed on the farms of their foster parents or learned a trade and married into a non-Roma-family. In a few towns the Roma assimilated completely into the village population. The process of assimilation is mirrored in the disappearance of the formerly multifarious family names in the conscriptions of the "Gypsies". In other territories of the monarchy, however, the Roma offered resistance against the way of life ordered by the state, they evaded the harsh compulsory measures and took to the road again. The state at this time lacked the necessary human resources to translate the regulations into action or to return the Roma that had escaped. Moreover, as they were generally completed according to the expectations of the authorities, the lists of conscription often did not show any need for action. In Germany similar measures, though on a smaller scale, were taken. A few sovereigns tried to make the "Gypsies" settle down on their territories, such as the Count of Wittgenstein, who had the "Gypsy settlement" Sa�mannshausen erected in 1771. Friedrich II of Prussia, a contemporay and rival of Maria Theresia, founded the "Gypsy settlement" Friedrichslohra in a remote area near Nordhausen in 1775 in order to make Sinti groups who had been "roaming the land as beggars and thiefs" settle down permanently. The attempt to transform the Sinti into the States idea of "clean, proper, obedient and diligent" people failed miserably. After 1830 the adults were committed to workhouses and the Martinsstift in Erfurt (a convent) took charge of the children. |

|

ROMA IN LIMBO Nobody knows how many Romani refugees there are in Italy. Campland: Racial Segregation of Roma in Italy, published by The European Roma Rights Center, Budapest, October 2000, gives one estimate of 130,000 and another of from 90,000 to 110,000. This, of course, includes the native Italian Sinti and Roma, who also live in these camps despite the fact that they are mostly Italian citizens by birth. The Italian government considers all Roma and Sinti to be nomads who must live in segregated camps. They are not allowed to settle and enter mainstream society. Many of the Romani refugees are from Kosovo, Bosnia, Macedonia and other regions of the former Yugoslavia, others are from Rumania. Many have been in these camps for ten, fifteen, or more years, some for decades. Their children, born in Italy, have known no life but the camps. They cannot apply for Convention-refugee status like Romani refugees in Canada. Few can obtain residence permits and most are unable to obtain work permits. Women must beg on the streets of the cities with their children in order to feed their families. The police have the right to take away their children and place them in foster homes. Nobody knows how many camps there are in Italy. Some are legal others are illegal. The difference is vague and fluid, depending on the whims of local municipal governments. Most of the Roma in the �nomad� camps came from former sedentary Romani communities in the Balkans and were never nomadic. This institutionalised nomadism applied to Roma by the Italian government is a gross violation of human rights. As a Romani activist who has been working in Canada with Romani refugees from many of the former Communist countries of central-eastern Europe, I was astounded that such living conditions and dehumanisation of my people could exist in a civilised western-European country. I and my colleagues were stopped at the entrance to Casilino 900 by plain-clothed Italian police who examined our passports and then warned us not to go into �this Gypsy camp. The Zingari will steal your cameras and rob you,� we were informed. They finally let us go in �at our own risk� as they put it. The first thing that struck me in Casilino 900, was the garbage piled everywhere around the makeshift hovels the Roma had built and the stationary trailers, most without wheels. There�s no garbage removal and all the camps are infested with rats which often bite babies and small children. No electricity, no running water except outdoor taps and no sanitation except the Sebach chemical toilets which were full to overflowing. Most of the lids had been destroyed and flies commuted from the accumulated excrement to the food the women were preparing on makeshift stoves outdoors where they cooked the family meals by burning wood and other refuse from the piles of garbage. In one camp, I did see a Sebach honey-dipper wagon driven by an Ethiopian refugee. He told me he makes one trip a month to that camp. Casilino 900, the Roma told me, was typical of most of the camps throughout Italy. Most of the Roma in this camp are refugees from the former Yugoslavia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia and elsewhere. Fortunately I was able to converse with the Roma in Romani since my North-American Vlach-Romani has now been augmented by having to converse almost daily with Romani refugees in Canada who speak a wide variety of Romani dialects from many former Communist countries of the Balkans. Most Roma told me their main problem is work permits and lack of legal status. They are not allowed to apply for Convention-refuge status. If they do, like one man and his wife with 8 children from Bosnia who arrived 11 years ago, they are denied and given 30 days to leave Italy or be deported. Italy does not apply the 1951 Geneva Convention on Refugees to Roma, like Canada does. Instead, the Italian government applies the 1954 UN New York Agreement for Stateless Persons. A few Roma have been able to claim stateless status and have been given residence permits like Babo Daniele who arrived in Italy after a stateless Odyssey through the hate-filled remains of the former Yugoslavia with a useless red Yugoslavian passport. Like thousands of Roma from the former Yugoslavia, he was without citizenship in any of the new republics, none of which was eager to accept more Romani citizens. Thousands of others, including former guest workers in western Europe, cannot return to Yugoslavia, even if they wished to, because the husband is a citizen of one republic and his wife a citizen of another. Many stateless ex-Yugoslav Roma who were refugees in Macedonia have also made their way to Italy. Babo Daniele now manufactures his own ovens to cook pizza and steaks in his workshop in the house he has built in the camp. This house has electricity provided by a noisy gasoline-powered generator he made himself from parts he scrounged, begged or bought. He sells his stoves to the Roma and non-Roma to make a living. He is a blacksmith by trade and told me he is trying in vain to get the Italian government at some level to advance a loan or start-up grant to create a small factory in the camp where he and other blacksmiths among the Roma could manufacture these stoves as a community work project. So far his appeals have fallen on deaf ears. Another invincible Rom is 80-year old Sevko R., a Chergari coppersmith from Bosnia who is still hammering copper and working as a metal-smith. He told me: � I�ve been hammering copper all my life and I�ll die with a hammer in my hand.� Other Roma are also skilled in making jewellery, beaten-copper pots and vases and other commercially-viable items but no interest has been shown by the Italian government to develop cottage industries or to fund self-help or employment start-up projects to enable the refugees to earn their own living. Many are blacksmiths, auto mechanics, tradesmen or have other viable work skills. Most of the men in Casilino 900 and in the hundreds of other camps, are demoralised. They are unable to obtain work permits and most survive on the begging of their wives and whatever odd jobs they can find. The Italian press condemns these camps as �breeding grounds for criminals� and there is no doubt that temptation towards fringe criminality exists since all honest avenues for gainful employment have been legally eliminated or denied. Education is another disaster. Some children do go to school in the few camps where school buses provide service but most do not or attend sporadically. Young boys vie with one another to learn the accordion since many of the men are able to eke out a living by playing music on the streetcars, the subway and in restaurants where they accompany themselves playing and singing popular melodies like O Solo Mio or La Cumparsita for European and American tourists who think they are Italian troubadours. Little girls face a career of begging or menial housework for rich Italians. In nearby Camp Luigi Candoni, inhabited by Rumanian-Romani refugees, children do attend school since there is a school bus service. Roma in this camp live in containers which are the best solution for refugees but there are too few of them available. The containers are about as comfortable as a mobile home in Canada with running water, indoor plumbing including bidets, electricity, stoves, refrigerators, and multiple small bedrooms. At first glance, this model camp, the only one of its kind, seems comfortable and pleasant and much better than the isolated, moth-eaten, no-star motels along the highways near Hamilton, Saint Catherines and in the Niagara Peninsula where the Toronto Shelters Committee is housing Hungarian-Romani refugees in Canada until you realise that these Roma in Italy may be here forever. The Hungarian Roma in Canada only have to stay two months or so in the motel rooms until they are able to leave, rent apartments, obtain work permits and begin to integrate into Canadian society while awaiting a decision from the Immigration & Refugee Board (IRB). If they receive a positive decision from the IRB they can apply to become landed immigrants and when landed, they can apply for Canadian citizenship. A negative decision by the IRB means an appeal and if this fails, deportation or voluntary return to Hungary. The negative side of the coin is that at present, only 12 to 18 percent of the Hungarian-Romani refugees are receiving positive decisions from the IRB in Canada compared to 89 percent for the Czech-Romani refugees in 1998. The main problem in model camp Luigi Candoni is hunger. Refugees in Italy are not given money for food and without the begging of the women, who travel daily to Rome, nobody would eat regular meals. The men cannot obtain work permits and are forced to find whatever work or self-employment they can in the underground economy. It is also almost impossible for the Roma to obtain medical care. One 27-year-old woman, seven months pregnant, went to a hospital in Rome with a dead foetus in her womb. She was given some pills and told to leave since the hospital was not responsible for �Zingari trash.� She insisted and finally she was placed alone in a room and left unattended where she suffered a miscarriage and a haemorrhage without the assistance of a doctor or nurse. When I met Camilia D. three months later, in October 2001, she was still bleeding intermittently and could not obtain follow-up care from that hospital or any other. The daily routine of Camp Luigi Candoni, like the others in the area, is dictated by hunger. Young mothers leave with pre-school children early in the morning to take the subway to Rome. They are allowed to beg anywhere except in Vatican City where they are forbidden and face arrest. While His Holiness did bless the Roma and refer to them as �My Beloved Children of the Wind,� he does not allow them to beg in his domain. In the evening, the mothers and children return and are verbally bombarded by the older women who sit along the walkways between the containers behind piles of clothing and other items obtained from charity organisations or kind Italian donors which they sell to their fellow Roma whom they hope might have a few extra lire to spare after a day of begging. Often, there was no food in the morning or maybe some stale bread and nobody ate breakfast so there is now a mad rush to prepare supper since the entire camp is hungry. Those who have food, feed those who have not. Next morning the cycle begins again. In some camps, the women have returned to find the camp demolished by bulldozers, their shacks a pile of rubbish and the Roma absent, hiding elsewhere until the fury of the municipal authorities, the racist police and the snarling bulldozers has abated and they can return to salvage what is left of their belongings. I left Italy with one question that I, as a Canadian-Romani activist, must ask myself. Where are our Romani leaders in Europe? Why are none of the leading Romani figures involved in this tragedy? Are they too busy attending endless conferences and fighting with one another over grants and allocation of authority? Are they too busy with their own aggrandisement and self-promotion to care about our people in these camps? In Canada we are doing all we can to assist the Romani refugees in a country where they do have the chance to be accepted as Convention refugees and eventually obtain citizenship. If I lived in Europe, I would be in Italy fighting for these Roma. Why aren�t our European Romani leaders and activists? The Gazh� will not solve this problem, only Roma activists and leaders. Non-Roma are helping, in fact they are providing most of the help at present but without strong Roma leadership, Limbo will continue to exist for these Romani refugees in Italy. On my last visit to Casilino 900, �Little Onion,� a 12-year-old loveable little rascal born in the camps and already a masterful beggar implored me: �Amico, le man tusa ande Kanada � Friend, take me with you to Canada!� I only wished I could. His request was echoed by many Campland Roma: �Kako! Azhutisar amen te djas ande Kanada. Meras ande Italiya � Uncle! Help us to go to Canada. We are dying in Italy.� The world needs to know about these camps, the institutionalised racism and the inhuman conditions under which the Roma are forced to live. Ronald Lee |

ME SEM YAD VASHEM Rajko Djuric Me sem Yad Vashem. Rat thaj praxo me naja. Pe mor palme anava. Me sem Yad Vashem. Jag xalem, Thuv pilem. An Auschwitz me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Pe kokala me sutem. Bi jakhengo achilem. An Treblinka me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Ratesa man uchardem. Bi morchako achilem. An Buchenwald me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Jasvenca me hiv handem. Krikosa trusul kerdem. An Dachau me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Rat thaj praxo me naja. Pe mor palme anava. Me sem Yad Vashem. Sa so sas man- Hasardem. An Bergen - Belsen me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Bi navesko, Bi lavesko achilem. An Ravensbr�ck me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Kaj me sema- Ni dzanglem. Dzanav numa kaj mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Ceri pe phuv perade. An kalipe man phangle. An Lublino me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Mor per pharade. An ma e chave chinde. An Jasenovco me mulem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Rat thaj praxo me naja. Pe mor palme anava. Me sem Yad Vashem. Semas kate, semas kote. Pe kale, ratvale rote. Praxo thaj thuv kerdilem. Me sem Yad Vashem. Sas man ilo rromano. Sar Rrom me sem mudardo. Me sem Yad Vashem. Rat thaj praxo me naja. Pe mor palme anava. Me sem Yad Vashem. Dzikaj boldel pe i phuv, Ni hasavola o thuv. Me sem Yad Vashem. Dzikaj o kham ka phirel, Yad Vashem si te ovel. Me sem Yad Vashem. Dzikaj o Del - Del ovela, O Auschwitz ni bistrela. |

Day of Remembrance Rajko Djuric I am Yad Vashem Blood and dust my nails On my palms I bring Yad Vashem I suffered fire I drank smoke In Auschwitz I died I am Yad Vashem I slept on bones Without eyes I became In Treblinka I died I am Yad Vashem With blood I covered myself I remained without skin In Buchenwald I died I am Yad Vashem With tears I dug my hole with Krikosa I made a cross In Dachau I died I am Yad Vashem Blood and dust my nails On my palms I bring I am Yad Vashem Everything what I had O lost In Bergen-Belsen I died I am Yad Vashem Without a name Without a word I remained In Ravensbruck I died I am Yad Vashem Where I was I don't know I know only that I died I am Yad Vashem Stars on the earth fell In darkness they imprisoned me In Lublino I died I am Yad Vashem My guts they shattered In me, the child they cut out In Jasenovco I died I am Yad Vashem Blood and dust my nails On my palms I bring I am Yad Vashem I was here, I was there On black, bloody wheels Dust and smoke I became I am Yad Vashem I had a Romani heart As a Rom I am murdered I am Yad Vashem Blood and dust my nails On my palms I bring I am Yad Vashem Until it returns on the earth The smoke will not be lost I am Yad Vashem Until the sun will falls Yad Vashem must come I am Yad Vashem Auschwitz will not be forgotten |

Remembrance ceremony in Klagenfurt, Austria (4th May) to Sinti and Roma Holocaust victims. |

(Thanks to Ronald Lee for the translation)

Romani Origins and Romani Identity. Dec. 2006 (580kb PDF)

|

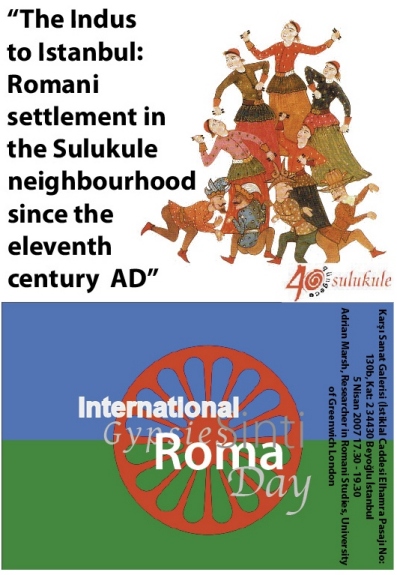

I was on line, searching into the background of the Dutch Settela Steinbach, more commonly known as 'the girl in the cattle train.'There were several mentions of the name of this iconic victim of the Second World War. One led me to the site of Yad VaShem where I read this intriguing comment. "For fifty years this child was believed to be an unknown Jewish girl. If you can read Dutch, you must read Aad Wagenaar's account of Setella." My first impulse was to shout, "Hey, what do you mean, if you can read Dutch! I can't read Dutch!" I clicked the blue cyberlink anyway, and found myself staring at the kind face of a bearded stranger and the text of an interview. The interview was in Dutch, a language I didn't know, but I managed to get the gist. I learned that the journalist Aad Wagenaar had been haunted throughout his life by the picture of the girl, often shown in Holland to illustrate stories about the Second World War. Wagenaar had written a book about his long struggle to find out the identity and fate of the beautiful child. His search revealed the fact that the girl was not Jewish, as had been assumed for so long, but a member of the Sinti Gypsy community. Born under a caravan. Forced onto a train. Murdered aged nine. At the end of the interview was the name and webaddress of the publishers, De Arbeiderspers. I emailed requesting a copy of the book, in any major language if possible, and in Dutch if it hadn't been translated. The following day I got this reply. "Sorry, the book only exists in Dutch, and anyway, it is out of print." OK, what now? Racking my brains, I contacted the Department of Romani Studies at University of Greenwich, the University of Hertfordshire, and Texas University. I emailed all the Roma groups I know. I asked them all if they had a Dutch copy of SETTELA. They hadn't. I phoned the Dutch Embassy. When I finally got past the numbers game - (if you want a visa press 2, if you want a work permit press 3) - I asked the slightly harrassed woman at the end of the line if she knew where I could get a copy of Aad Wagenaar's book, SETTELA. "What is Settela?" "Um, Settela was a girl killed in the Second World War." "We have no books, we are an Embassy, not a library!" At this point I almost gave up, but like Aad Wagenaar, I'd now become slightly obsessed by my quest, so I wrote to De Arbeiderspers again and begged them to put me in contact with the author. A week later, I got a charming email from Aad himself, saying that he only had two copies of the book, which he wanted to keep. "But you might get hold of the book in Holland at a car boot sale, and it should be in most of our Dutch libraries." I asked for more precise details, adding that I intended to translate the book into English. I don't know why I suggested this - it's arrogant in the extreme for a non-Dutch speaker to undertake such a task. But my offer did the trick. Realising that he wasn't easily going to get rid of his email stalker from England, Aad agreed to find me a copy. About a month later, I had a strange dream of a young girl looking wistfully from a barred prison window the night before her death. In the morning, I found a brown packet on the doormat. It had a Dutch postmark, and on opening it, I found the slim volume of SETTELA. It took me about a week to finish the book. I read it in the evenings, underlining words I couldn't understand. This means almost every other word. The first passage seemed quite simple - it started, "De beelden duren maar zevven seconden", which to anyone with a knowledge of German and English is perfectly understandable, but the beginning of the next chapter seemed totally incomprehensible, - apparently an account of 19th century whiteplastered houses - which seemed to have no bearing whatsover on the story. However, struggling to the end of the book I was able to make some sort of sense of the account. Then, armed with a large Dutch dictionary, I started looking up the unknown words. When I was satisfied my translation was as good I could make it, I wrote to Aad again, asking if he'd like to see it. He said he'd be happy to look at my poor translation and help with the more difficult passages. I emailed my draft before he could change his mind, and a few weeks later went to Den Haag to discuss the translation. Back in London, I worked on the final draft. All this carry-on turned out to be the easy bit. The next stage was to find a publisher. I spent hours with my nose stuck in the Writers' Year Book, and vast sums of money posting the manuscript to all the major publishers. Without exception, they returned my synopsis with that well-known and intensely irritating sentence, "Thankyou for thinking of us, but your work is not quite suitable for our list." There exists in England, in Nottingham to be precise, a small literary press with vision and a committment to unconventional themes, the admirable Five Leaves Publications. At last SETTELA was accepted, and published in March 2005. The book is an unusual addition to the enormous body of work about the Holocaust. It's a strange mixture of historical facts, interviews with Jewish and Sinti survivors, and Aad Wagenaar's personal feelings of obsession and grief. On one level, it's a simple detective story, on another, deeper and darker level, it's an account of persecution and genocide. Aad's remarkable story reminds readers that the Holocaust devastated many groups, including the Sinti and Romani people. And although the picture of Settela is over 60 years old, her lovely, haunting face staring from the cattle wagon emphasises the timeless message - that children still suffer through cruelty and war. And that Romani children and Travellers are still being moved on and still suffer persecution. Janna Eliot |

|