|

British troops were told in lectures that the Japanese were small, myopic and technically backward. Popular cartoon images of the Japanese promoted the idea of tiny, strutting men in glasses brandishing samurai swords, with buck-toothed grins and slanted slits for eyes.

Col G.T. Wards, the British military attaché in Tokyo, on April 1941 gave a factual and frank account of the quality of the Japanese armed services to an audience of army officers in Singapore; highlighting among other things that the Japanese were fully aware of British weaknesses in the Far East. He was publicly contradicted and denigrated at the conclusion of his lecture by the GOC, Lt. Gen. Bond who later told him in private that "We must not discourage the chaps and we must keep their spirits up." The Japanese of course were not fooled by the deliberate bluff.

"I misjudged the Japs. I did not realise for a long time what

terribly efficient and serious soldiers they were."

"Everyone talks about fighting to the last man, but only the Japanese actually do it." Gen. Sir William Slim remarked during the Burma campaign in 1944

Japan attacked China because of low silk and high oil prices and because they wanted to build a large empire. In 1929, two-fifths of Japan’s export income came through selling silk to the US, but the depression destroyed that market. One reason for Japan attacking China was to try and get more resources so they wouldn’t have to depend on silk and to try and compensate for their losses. Another reason for war was a lack of oil. Oil was an important resource to the Japanese but unfortunately they had none of it. Japan attacked China, looking for more raw materials and land to build their empire.

"I think we grew too much. We had a large population with almost

no resources. Virtually the only things we could export were fish

and silk. We were okay until the 1920’s, but that’s when the US

stopped buying our silk. The price of silk plummeted and we had

to go to China to get other resources. I think in a way, we were

forced to fight in the war because we were either going to become

a modern nation by getting resources, or stay like we were, an

old fashioned farming country." /apwh/bios/i4tamura.htm |

Offering at a gravesite for Japanese soldiers killed in action.

Mainichi Shimbun

Japanese soldiers advancing on a hillside in Singapore

Asahi Shimbun Company

Fording a water obstacle.

Mainichi Shimbun

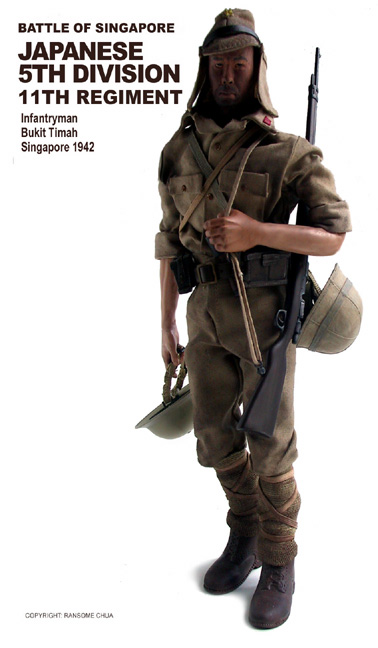

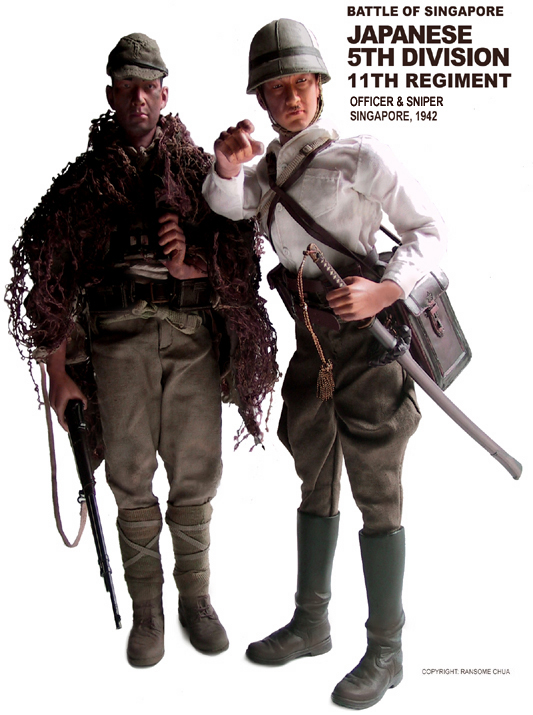

The Japanese soldier during the Malaya-Singapore campaign

The 3 Japanese divisions used in Malaya were not as, urban legend

had it, hardened jungle fighters simply for the fact that they

never had any experience of jungle fighting. What they had was

hard, rugged training on Hainan island off the south China coast

and in Indochina, to prepare them for their Malayan venture. The

fact that they were not jungle veterans was also not important

because the land on the western coast of the Malayan peninsula

was under intense cultivation with pineapple and oil palm plantations,

rice fields and rubber estates. These cultivations necessitated

a network of estate roads that were used by the Japanese to bypass

and outflank British positions on the trunk or main road. Tactically

mobile with bicycles, pack animals and fewer trucks, they were

also more adaptable in cross-country movement unlike the British,

who were dependant on wheeled vehicles and had to keep to the

roads. The Japanese were also very experienced in fording rivers

and streams.

The Japanese used veteran troops, 2 of the 3 divisions used in

the Malayan campaign had served in China; these men were physically

tough, confident, well trained and aggressively led and they were

prepared for close country warfare - which the British were not.

The Japanese also had command of the sea and air. One element

often not highlighted was the prowess of the Japanese soldier

in using psychological warfare to create the impression of being

a bigger force when outflanking the British forces. Troops were

deliberately spread out during a swift, intense attack to pop

up briefly and draw fire while the attacking party would break

into smaller groups to encircle the enemy. Booby traps, firecrackers

thrown into enemy positions, bogus commands given in English or

Urdu and exploding bullets were used to create the impression

of larger numbers and generate confusion in the ranks of the by-now

bewildered enemy.

All these were much important than the 'fanaticism' on the part of the Japanese soldier, characterised by Australian Gunner Russell Braddon, as "squat, compact figures with coarse puttees, canvas, rubber-soled, web-toed boots, smooth brown hands, heavy black eyebrows across broad foreheads, and ugly battle helmets. Each man wore two belts - one to keep his pants up and one to hold his grenades, his identity disc and his religious charm - and when they removed their helmets, they wore caps, and when they took off their caps, their heads had been shaved until only a harsh black stubble remained. They handled their weapon as if they had been born with them. They were the complete fighting animal."

Two interesting accounts of the Japanese soldier during World

War 2 are provided by writers Ralph Modder and Henry Frei:

In Modder's book - The Singapore Chinese Massacre - the Japanese

soldier is defined as "the 'ideal warrior,' fighting without food or water, trained

to live off the land so that supplying troops was never a major

problem at the outset of the war, sustaining himself on his ability

to withstand pain and hardship accepted as part of a soldier's

duty. He obeyed orders to commit suicide or to carry out suicide

attacks without question and was happy to know that he would die

like a hero for his Emperor. He was ready to be blown to pieces,

shot or horribly wounded. Above all, he welcomed death.

Prime Minister Tojo had made it clear that if a Japanese soldier

allowed himself to be taken prisoner, he should be executed even

if he escaped and rejoined his regiment. Furthermore, his family

would suffer the shame of his cowardice. Japanese army commanders

failed to understand why surrendered Allied troops who were in

good health should be treated with special care. To them, it just

didn't make sense.

The Japanese were not born with the fearsome and fearless qualities

that had made them such legendary warriors. They were moulded

into robot-like 'exterminators' by brutal training methods and

in indoctrination courses in which tyrannical instructors instilled

in recruits the belief of their 'superiority' as warriors; that

through suicidal acts in battle they would reach god-like status,

their spirits forever revered at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, the

resting place of the spirits of all national heroes. The Japanese

soldier's duty was simply to obey orders. Death was part of it."

Indeed, death was part of a Japanese soldier's duty. Shortly after

midnight on the 8th of February, 1942, in the boat assault of

Singapore island, Leading Private Kioichi Yamamoto, one of the

coxswains steering his craft towards the enemy shore under fire

was probably under no illusions that he was not going to see through

this war alive. Halfway across the straits, he was hit by sharpnel

in the stomach, chest and right hand, probably from a mortar bomb.

His boat's steering damaged, the coxswain insisted on staying

at what was left of the wheel until the infantrymen in his vessel

disembarked on shore. Gasping for breath, Yamamoto then collapsed

and died but not before wishing His Imperial Majesty a long life

with a last 'Tenno haika banzai!' When he was picked up, it was discovered that his right lung

was protruding through his shattered rib cage and almost his entire

uniform was soaked with blood.

Sgt. Arai Mitsuo of the 18th Division was part of the second wave

when at about 1 a.m., jumping from the bow of his boat he felt

as he recollected in the 3rd person, "a cold hand stroked his ankle. Nine corpses floated in the water,

head upward, in a line next to each other. A chill ran down Arai's

spine. Were they shot while crossing, and then washed up, or after

they had landed? But reflections be hanged! Quick! Cut off a wrist

or a finger of each dead man. Chop, chop, chop. Into a box, there's

no time to bury them. Just a quick prayer. Rest in peace. Then

forward! He must fire the green 'success' rocket: Regimental Command

has landed - the sign for 18th Division Gen. Mutaguchi Renya to

embark on the third wave across the straits."

After a battle, prior to the corpses being buried, the wrists

or fingers of the Japanese dead were hacked off and put away in

a container for ossifying. During a lull, one would burn away

the flesh and give the bones to one of the deceased's close comrades

for him to take care of until the remains could be returned to

his hometown in an urn. Imperial Guard Tsuchikane recounts his

morbid experience, writing of himself in the third person:

"The platoon commander ordered him to cut off dead Captain Matsumoto's

wrist and lent him his company sword to do the job. It would not

cut. Tsuchikane tried again and again and finally the bone snapped.

They dropped the severed wrist into Matsumoto's mess tin and put

it carefully away into the ordnance bag of Senior Soldier Otsuka

who hailed from the same province... After a further battle, they

were able to rest in a bomb-out house. First they took from the

mess tin the dead Captain's hand and began to grill it. "Shuu,

shuu," it sizzled, with lots of grease escaping from the hand.

Strong smoke with a dreadful stench soon filled the room... Their

chopsticks got shorter, catching fire many times owing to their

efforts of turning the flesh and then burning away the muscle

from the bones...Picking the bones from the charcoal, they transferred

them to a British tobacco tin, which they passed to the safe-keeping

of their war buddies. They, in turn, put the bones in a white

cloth and stored the package with great care in their service

bag.... The soldiers had promised each other that they would enter

Singapore together, even if it were only their remains. They had

fought together until today, they had eaten the same rice, dived

under the same bullets, and they felt a bond no different from

that of brothers. Perhaps it was even stronger by knowledge of

man's fleeting existence experienced each day over the past months."

How were such fanaticism inculcated or bred in the soldiers of

the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA)? The samurai caste had already

been abolished in 1868 when Japan went to war in 1941. Modder

writes that Japanese premier General Hideki Tojo quickly "seized the opportunity to incorporate samurai ideals into the

Senjinkun (Warrior Code) that was taught to officers of the Imperial

Army whose harsh treatment of troops under them was a distortion

of the original ideals of bushido (Way of the Warrior). Troops

were ordered by their officers to make suicidal attacks against

enemy forces or fortifications, as had happened in China. In battle,

troops were expected to find the quickest way to end their lives

to avoid being taken prisoner. Also conveniently erased from the

original principles of bushido were 'courtesy and kindness. No

Western army was able to match the Japanese for courage. As Gen.

Sir William Slim remarked during the Burma campaign in 1944, "Everyone

talks about fighting to the last man, but only the Japanese actually

do it."

Writer Henry Frei, in his book Guns of February, which gives an intimate account of the ordinary Japanese soldier’s combat experiences during the battle for Singapore, focuses on the other hand, on the recollections and complex emotions of humanity, brutality, callousness and contritions of the Japanese soldier operating at the sharp end of war. Frei’s account goes beyond the conventional view of the Japanese soldier as a fanatic ready to die in the service of the Emperor, for he writes of the helplessness of some of the Japanese soldiers who were forced to obey military orders to commit atrocities against the Singapore Chinese civilian population during the Sook Ching (Purification through purge) massacre; "Now you must obey orders," the commander said. "You must now kill these Chinese." Kill. They had to kill them. Miyake and his collegues harboured no hostility against their assigned group. They couldn't stir up any hostile feelings. They had been done no harm by the Chinese people, they had no reason to take lives, no murderous intentions, they did not want to kill. They were human beings. People. To raise their will to kill the people, the officer in charge said: "You are about to kill these people by order of the highest general, the Emperor." Then he proceeded to cut off the heads of two of them. he did it with his sabre. The blood came out in a hissing sound - "shooo!" - and spurted two or three metres into the air, spraying around. Another 12 were beheaded, the rest stabbed... "The Emperor now orders you to kill..." Miyake never ceased asking himself: Does the Emperor have this right? Can he give such an order?

Frei notes that some of these veterans, in their old age, have

expressed remorse and contrition for perpetrating the atrocity.

One of these was former Kempeit-tai Lt. Onishi Satoru, "... Japan's biggest mistake at the beginning of the Occupation....

As a person who was involved, I feel as if stabbed by a knife,

aware of my responsibility towards the victims, to whom I offer

my sincere and deep condolences. I am not trying to justify or

excuse ourselves. The purge was a cruel act committed by the Japanese

Army. It constitutes truly shameful behaviour, and remains a most

disgraceful act in the Great Eastern War."

Machine-gunner Ochi recalls: "Japan was doing too well at the beginning of the war. The attack

on Pearl Harbour, the conquest of Singapore, the sea battles successes

off Malaya, the occupation of one place after the other in Indonesia,

and so on, each fed on the other and led to Japanese self-pride

and conceit. Drunk as they were on their sole object of winning

the war, generals were aiming at glory, their juniors at a rise

in career, the people at a net profit out of the war, each seeking,

with characteristic impatience and a quick temper, their own "net

profit." Yet, after their tiny victories, to get proud and arrogant

so quickly and to give free rein to self-interest and even public

black markets, was truly deplorable. If such Japanese had controlled

and ruled Asia, it would have become a miserable and pitiful place,

indeed.

The Japanese had not yet evolved into a constitutional people.

So there was really no reason to challenge the United States or

great Britain who were already constitutional peoples. The biggest

reason for Japan's defeat was her backwardness. It was good that

Japan was defeated. Japan can now completely reform and remodel

itself and its cultural standards. It's the young that must do

this. Only the young can complete and achieve this."

However, in retrospect, the absence of moral courage among Japanese

soldiers to defy unlawful military orders showcased the moral

degradation and depravity of the Imperial Japanese Army. Evidence

of the callousness and brutality of the Japanese soldier is provided.

In one instance, Imperial guardsmen had mistakenly fired on Malayan

civilians. Instead of rendering first aid to the badly injured

survivors, the guardsmen systematically finished them off one

by one on dubious mercy killing grounds. It was clear that the

fanatical fighting spirit of the Japanese soldier also inured

him to indignities inflicted upon enemy civilians and surrendering

soldiers.

Imperial Guard Tsuchikane relates his platoon's first contact

with the Australians after landing and marching inland towards

the Mandai area: "Amid the platoon's murderous yells, Tsuchikane hurled himself

forward, straight into the enemy position. Many of the Australian

27th Brigade were already turning their backs to him. Tsuchikane

closed in on one, ran after him, pulled him to the ground, and

with his bayonet pierced his opponent from the back of his shoulder

out through the front. The enemy expired with a deathly yell,

as Tsuchikane pulled out the blade, splattering his jacket with

a crimson red.

The Australian position had stood on a slight rise and the Aussies

had put its height to good use by concentrating heavy flank fire

from a fixed position down onto the approaching Japanese enemy.

Many of the dead lay just beneath the rise. Having lost their

minds, some of the defenders had simply been cowering in terror,

trying to squat down and avoid hand-to-hand combat. They, too,

were bayoneted and shot without mercy.

The company captured a number of heavy machine-guns and 18 prisoners

of war, several among whom were British, including a red-bearded

officer. The prisoners, however, were dangerous baggage. Taking

them into the next battle would greatly hamper tactics. They would

require several guards at a time when the attackers themselves

had suffered 60 dead and wounded and the battle for Singapore

was just beginning. Fortunately, an artillery unit in the rear

was willing to accept the 18 prisoners, to the great relief of

the Imperial Guard company.

Remembering the sordid incidences by Japanese troops in China,

Gen. Yamashita's first order to the Japanese invasion forces assembled

at Sanya in Hainan Island prior to the start of the invasion,

was "no looting, no rape, no arson." The general made it clear that any soldiers committing such crimes

would be severely punished and their superior officers held accountable.

Some of Yamashita's fears were realised when Japanese troops occupied

the Malayan island of Penang on the 19th December, 1942. Incidents

occurred in which some soldiers committed the crimes of looting

and raping, despite notice given on 11 December that military

discipline would be strictly enforced. These soldiers involved

were ordered to be severely punished and their regimental and

battalion commanders disciplined. In his diary, Yamashita wrote

angrily, deploring the fact that his orders had not been heeded

by soldiers and stressing that the re-education of the Japanese

in discipline and morality was necessary.

References:

Ralph Modder, The Singapore Chinese Massacre, Horizon Books Pte Ltd, Singapore, 2004

Henry Frei, Guns of February: Ordinary Japanese Soldiers’ Views of the Malayan Campaign and the Fall of Singapore 1941 - 42, Singapore University Press, 2004

Brian Farrel & Sandy Hunter, Sixty Years On - The Fall of Singapore

Revisited, Eastern Universities Press, 2004

www.mindef.gov.sg/imindef/publications/pointer/journals/2004/v30n4/book_review.html

www.malaysia-today.net/books/2006/03/20a-japanese-invasion-ibrahim-yaakubs.htm

|

Japanese Invasion: Ibrahim Yaakub’s recollections of Japanese

soldiers They came to Matang in search of food, especially chicken, ducks

and eggs. Chinese folks, who stocked rice and flour in their homes,

hurriedly bundled them up in water proof containers before lowering

them into the water. Some, in complete fear and panic, just threw

whatever they had into the water. Girls and young women slipped into the water under their homes

through openings made in the floorboards. Once the Japanese troops

had left, they climbed back into their homes once again. That

was the scene in Matang, which happened to be under flood waters.

I saw these spectacles from my hiding place across the river. Japanese soldiers, who arrived in trucks or on bicycles (the bicycle

brigades), were seen bashing a few Chinese who refused to part

with their possessions. Bicycles were simply snatched away or

exchanged with Japanese ones. Japanese soldiers loved bicycles

which were made in England especially the speedy Raleigh to

chase after enemies called Inggerisu (Englishmen). No one desired their Japanese-made bicycles, even

when given free. Only one bicycle in Matang, even being brand

new, escaped confiscation. It belonged to an Indian Public Works

Department supervisor. Many a Japanese soldier had grabbed the

new bicycle with a big grin, but when they measured the distance

between the seat and the pedal, they returned the bicycle with

a snigger and an “Arigato” (thank you). At 28 inches, it was too high for the Japanese soldiers,

who were, by and large, very short." |