A bridge too far... Operation Market Garden

Many young men gave their lives in a fight for bridges that lead to freedom, but one bridge proved to be, a bridge too far.

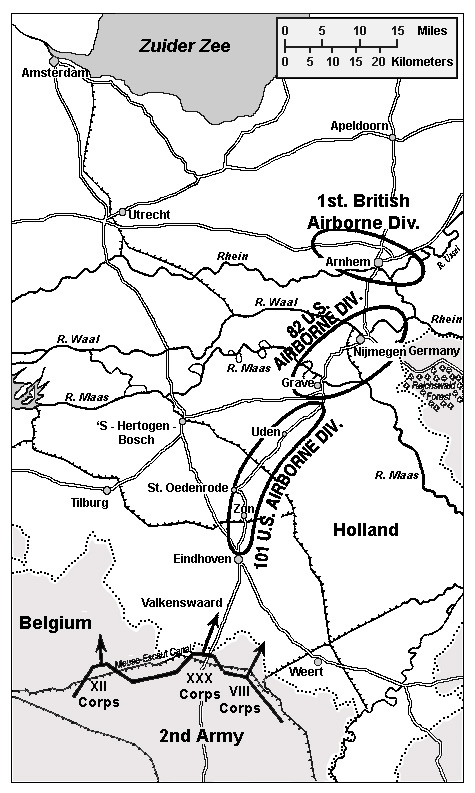

After the landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, and the operation to breakout from the beaches of Normandy called Operation Cobra, plans were made among the allied commanders, and debates were run to see what was the best way to strike the German Army further in Europe. After the initial landings in Normandy there were enough allied soldiers to form several armies. Under the command of Omar N. Bradley was the 12th US Army Group, under the command of General Courtney H. Hodges was the US 1st Army, and under the command of General George S.Patton was the 3rd Army. The US forces were roughly positioned on a line running north-south near the German border. To the north of these US Armies was the British 21st Army under the command of Bernard Montgomery. They help the north-east corner in a line from a town called Antwerp located in Belgium to the US Armies. To the far north on the coastline was the Canadian 1st Army. There were several plans and proposals by the allied commanders on how to end the war as quickly as possible. The plan of the supreme commander of allied forces, general Dwight D. Eisenhower, was to maintain a broad powerful attack on Nazi forces throughout the front line. But British general Montgomery, US general Patton, and general Bradley had other plans. Bradley and Patton favored an attack east from Patton's current positions to take the city of Metz, and then into the industrial area of the Saar. However this required passing the Siegfried Line of defenses at the German border, and left them in front of the equally heavily defended Rhine. As a defensive maneuver it was an excellent plan, as it would leave the Allies in control of the easily defended west bank of the Rhine. But as an offensive plan it did little other than take more land, and left them in an only slightly better position to assault Germany, so this plan was dismissed by general Eisenhower. Montgomery initially suggested a limited airborne assault, Operation Comet, consisting of an airborne assault in front of the British 30 Corps. Operation Comet was dropped in favor of a more ambitious plan, consisting of an attack north to Arnhem, deep inside the Netherlands, bypassing the Siegfried Line (which stopped about 20km south of there), crossing the Rhine, and capturing the entire German 15th Army behind their lines between Arnhem and the shores of the IJsselmeer. This would also have the side effect of cutting off the V-2 launch sites, which were bombarding London at this time. Montgomery pointed out that his plan ringed the entire Antwerp area well behind Allied lines, allowing it to be easily opened once the attack was completed. Both Patton, and Montgomery constantly asked for all available supplies to be sent to them in order to provide a quick and effective attack on Germany. The advance of the Allied troops effectively had to be stopped due to the ease with which they were overcoming the German defense positions, especially the Canadian, and British troops which encountered very little resistance in their regions, and had little trouble overcoming the German positions. In fact they were so fast that the supply lines couldn't keep up with their progress, as the only supply point was on the already secured docks made on the coast of Normandy after the D-day landings. General Eisenhower quickly realized this problem, and was most interested in opening the vital port of Antwerp located on a river near the coastline which was already under the 21st Army British command lead by the General Montgomery. The problem was that the river Westerschelde running from Antwerp inland was still under Nazi occupation. The Canadian forces have captured the vital regions just to the south of the British 21st Army, and Eisenhower was hoping that these forces after their successful operations could push further inland, and capture the vital regions around the river Westerschelde, so that the Allied supplies would gain another supply point in the city of Antwerp. The decision was apparently finally decided by command in the US. After the D-Day invasions the airborne forces had been withdrawn to re-form in England, forming the 1st Allied Airborne Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton. This consisted of three US and two British airborne divisions, and an additional Polish Brigade. Eisenhower had been under intense pressure from the US to use these forces as soon as possible, so in somewhat unlikely fashion this favored Montgomery's plan. The plan of action consisted of two coordinated operations, Market which was the use of the airborne troops, and Garden consisting of the British 2nd Army moving north along highway 69, spearheaded by 30 Corps. For the Airborne units three of five divisions of the 1st Airborne Army were employed consisted of about 30,000 men. The US 101st Airborne Division would drop in two locations just north of the 30 Corps to take the bridges northwest of Eindhoven at Son and Veghel. The 82nd Airborne Division would drop quite a bit northeast of them to take the bridges at Grave and Nijmegen, and finally the British 1st Airborne Division and Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade would drop at the extreme north end of the route, to take the road bridge at Arnhem and rail bridge at Oosterbeek. It was to be the largest airborne operation in history, conducted in a series of three huge operations known as "lifts". Commander of the 1st Army added his own HQ to the first "lift" so that he could command from the front and have a better view of the situation. Garden consisted primarily of XXX Corps, the core of the 2nd Army. They were expected to arrive at the south end of the 101st's area on the launch day, the 82nd by the second day, and the 1st by the third or fourth day at the latest. They would also deliver several additional infantry divisions to take over the defensive operations from the airborne, freeing them for other operations as soon as possible.

The rout of the 15the German Army had ended with the arrival of Field Marshal Gerd von Runsdedt. Runsdedt who replaced Field Marshal Walther Model, was generally detested by Adolph Hitler, but he was well liked by his troops, whom he had back in fighting condition by the end of the first week since his arrival at the new position. Most of the men from the German Army escaped from the pocket between the Canadian 1st and the Westerschelde, adding about 80,000 men to the area just northwest of the attack route. Runsdedt immediately began to plan defense against what Wermacht intelligence said was 60 Allied divisions at full strength but in reality Eisenhower, at that time, actually had only 49 divisions at his disposal. Colonel General Kurt Student, Wermacht's own airborne infantry pioneer, was ordered to take up positions with the remains of the First Parachute Army along the Albert Canal. Student's 3,000 paratroopers, scattered across the Reich, were probably the only combat-ready reserve forces in Germany at the time. Furthermore, Lieutenant General Kurt Chill, commanding the scattered 85th Division, established 'reception stations' at key bridge crossings in Holland. Chill's actions gathered together the remains of service troops into a semblance of military units, which allowed Student to organize a defensive line. What should have alarmed Allied planners of the operation was an unrelated event taking place nearby. When discussing the Allied plan of attack, Rundstedt and his generals agreed that Eisenhower would favor Patton. In one of his final orders as Commander-in-Chief West, Model ordered the troops of the II SS Panzer Corps, made up of the 9th SS and 10th SS Panzer divisions under the command of Lieutenant General Wilhelm Bittrich , to rest and refit in the rear. A suitable quiet spot was selected, which happened to be Arnhem. This meant another 9,000 troops in the area, all of them elite armored forces with heavy weapons. There were intelligence reports from Holland arriving in Allied headquarters, but were basically ignored as everything was almost ready for the following offensive, and the Allies learned not to trust reports from Holland Intelligence too much, as they proved to be unreliable before. In addition one reconnaissance airplane was sent from the 1st Airborne Army, and returned with the pictures of already mentioned heavily armored Panzer troops just north of Arnhem, but those pictures were ignored as the allies tot these tanks were broken down, and couldn't be deployed in action. There were even worse reports from the RAF Transport Command, saying that they are short of airplanes, and that and sort of bad weather could seriously upset the operation. They even refused to drop the British troops to the north of their target bridge because it would put them range of German flak guns just to the north of Deelen. The area to the south was too marshy and unsuitable for the dropping of troops, as most of them would probably drown with their heavy equipment, and would be easy targets for the Germans. Instead it was requested that they be dropped 15 km away from the bridge, which would just have to be taken and held over night until the 3rd lift arrived. This ultimately meant that this powerful force would have to be split for more than a day. Realizing the seriousness of the problem, the plan was then hastily changed to task the small force of machine-gun equipped jeeps in the reconaisance squadron with seizing the bridge in a coup de main, and holding it until the infantry could arrive. Three brigades would follow on foot, with the fourth and all the glider pilots holding the drop zones while they waited for the next two lifts. In a strangely short period of only one week, the largest airborne operation in history seemed to be ready...

The Allied operations began on September 17, 1944 with success. The operation was launched in daylight and almost all troops arrived on top of their drop zones without an incident. This was a huge contrast in comparison to previous night droppings which resulted in troops being scattered in an area of about 20 km in some cases. The operation called for the air support of the First Airborne Army comprised of the 101st and 82nd U.S. Airborne Divisions. They landed behind enemy lines in line about 60 miles long leading from the British lines to the city of Arnhem cutting Holland in half and clearing a way for the British motorized units all the way to the German border. The Allied troops were also to seize the key communications cities of Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem. the objective of the 101st was to capture the first 20 miles of this corridor, and the 82nd had the central part. Near Arnhem was the British Airborne division. The task of the British XXX Corps was to push forward to the north with heavy armor and link up with the Airborne units. In the south the 101st Airborne meet little resistance at the bridge of Vegel and quickly captured it, but a small incident with German anti-tank guns resulted in the German forces blowing up a small bridge at Son as they retreated. Later that day several small attacks by the 15th German Army were beaten off and the 101st moved south of Son. During that same day the 505th which was a part of the 82nd Airborne division had to fight fiercely counting about 80 men at Groesbeck against a whole Infantry Battalion of German forces supported by German armor. They held their positions despite three devastating attacks by the German forces. For these actions the whole 505th received the second Presidential citation. The 82nd parachuted at Grave and controlled the key river crossing there. One force had the task of capturing the bridge at Nijmegen, but due to miscommunication, they didn't start until late evening, and by that time it was too late, and they never captured the bridge, thus leaving it in German hands. Although the 101st Airborne, and the 82nd Airborne almost achieved their objectives, the situation at Arnhem was far more serious, and problematic. The British lst Airborne Division, reinforced by a Polish airborne unit, was dropped too far from its target, the Arnhem bridge, and more fundamentally, German strength in Arnhem was substantially greater than anticipated in the intelligence estimates. Over half the reconnaissance jeeps were lost during the landings, and the rest of the forces got ambushed trying to push forward into the city of Arnhem, so the only hope of capturing the city was on foot. The progress of the troops that landed was largely slowed down by the German defensive positions, so the decision was made to wait for the second landing, and try again tomorrow. The two bridges at Nijmegen and Arnhem, were of vital importance because unlike other bridges that were already captured that only crossed small canals, that could even be over passed by the engineering units, these two bridges were crossing larger bridges, and if none of these bridges were captured, there was no way of XXX Corps reaching them, yet by the end of day one only a small force held the bridge at Arnhem, and Nijmegen was still in German hands. To make matters worse the communication equipment, and radio sets didn't work, and the British troops had no communication what so ever. On the German side things were not much better, largely because it wasn't clear at the start what was going on. Model, in direct command of the forces in the area, was completely confused by the British dropping in what appeared to be the middle of nowhere, and concluded they were commandos attempting to kidnap him. Meanwhile Bittrich, commanding the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, had a clearer head, and immediately sent a reconnaissance squadron of the 9th SS Panzer Division to Nijmegen to reinforce the bridge defense there. Lightly armed Allied paratroopers found themselves up against two SS panzer divisions that had recently been refitting in the area. The British/Polish force, suffering from the loss in the airdrop of critical vehicles, artillery, and communications, failed to seize the Arnhem Bridge despite a heroic fight. The British armored column, which was to break through to relieve the airborne forces, fell behind schedule as the tanks crawled along the narrow, congested roadway. The operation ended less than 10 days later, with the British and Polish airborne troops surrounded in Arnhem and the armored column stalled 10 miles away. On the 18th of September the two British brigades trying to push forward to capture the bridge at Arnhem, were beaten off by the 10th SS forces that just arrived. The second lift that was expected arrived late due to the Fog in England. To the south the 82nd found it hard to fight the German forces at Grave, and soon one of the landing zones for the second lift was captured by the Nazi forces. In the meanwhile 101st faced with the loss of bridge at Son, attempted to take a similar bridge at Best. They soon found their way to be blocked by heavily armored Nazi forces, and they gave up. Some Units proceeded to the south and eventually reached Eindhoven. At about noon they meet with a reconnaissance unit from the 30th Corps, and soon established radio contact with the main force to the south telling them about the bridge at Son, and asking them for a bailey bridge to be brought. By the end of day 2 both vital bridges still lay in German hands. By this point most of the 1st Airborne was in place, and only the Polish brigade was yet to arrive in the 3rd lift later that day. Yet another attempt was made to reinforce Frost at the bridge, and this time resistance was even stronger. It appeared that there was no longer any hope of reaching the bridge, and the isolated units then retreated to Oosterbeek, to the west of Arnhem. Meanwhile at the bridge German tanks were arriving to take up the fight, which was becoming desperate. At 5pm a small part of the Polish units in the third lift finally arrived, but fell directly into the waiting guns of the Germans camped out around the area. With the radios not working they still had no way to tell the HQ that the landing zone was taken and many of the Polish troops were killed. At the same time several of the supply drop points were also in German hands, and the 1st retrieved only 10% of the supplies dropped to them. Things were going somewhat better for the 82nd, who found advanced units of 30 Corps arriving that morning. With the support of tanks they were able to quickly beat off the Germans in the area, at which point they decided to make a combined effort to take the bridge; the Guards Armored and 505th (part of the 82nd) would attack from the south while the 504th would cross the river in boats and take the north. The boats were called for to make the attempt in the late afternoon, but due to huge traffic problems to the south, they never arrived. Once again 30 Corps was held up in front of a bridge. The 101st had to give ground to a powerful German attack but as the British tanks came to the rescue, the Germans were soon beaten off. Some German tanks arrived as well firing at the bailey bridge, but were soon beaten off by the anti-tank fire from the British troops, thus securing the bailey bridge. Frost's force at the bridge continued to hold on and as the radios started working they soon found out that the rest of the division had no hope of relieving them, and that the 30th Corps were stuck at the Nijmegen bridge. By the afternoon the Germans had complete control of the Arnhem bridge and started setting fire to the houses the British were defending. The rest of the division had now set up defensive positions in Oosterbeek to the west of Arnhem, waiting for the arrival of XXX Corps. In Nijmegen the boats still didn't arrive, so the decision was made to cross the bridge in daylight in what is generally considered one of the bravest moves in military history. They made the crossing in 26 rowboats into well defended enemy positions. They soon made the Germans to push back, thus the vital bridge of Nijmegen was finally in Allied hands. To the south the 101st continued fighting various German units, and the German tanks cut off the roads again, retreating only when they ran low on ammunition. The Frost's force of British troops in Arnhem was cut down to only two houses, and out of ammo with the last message intercepted by the German operators "out of ammo, god save the King" they surrendered. Meanwhile the Guards Armored sat still while their commander refused to move forward while the town to the south, Nijmegen was still under constant threat. they radioed back along the line for the 43rd infantry division to come and take the town, but there was a 30 mile long traffic jam behind them, and they arrived only the next day. Still any German troops that tried to approach the Guards Armored found them self under fierce shell fire. By this time the Germans were desperate, and the Allies have certainly gained the upper hand. The Guards Armored had in their range the town of Arnhem, and they opened fire on German defense lines around Arnhem. The Poles in the meanwhile found them selves stuck, and had no idea of what the situation was in Arnhem. Two British soldiers made it across the river, and informed the Polish of the desperate situation asking them for any help they could provide. Poorly equipped the brave Polish troops promised to try and make a crossing of the river that night, but only 52 soldiers made it across the river. However the Germans had other ideas, and during the previous night had organized two mixed armored divisions on either side of highway 69 at about the middle of the line between Veghel and Grave. They attacked and only one side was stopped, while the other made it to the highway and cut the line. Any advance on Arnhem was now impossible. The Germans figured out what the Poles were trying to do, and launched attacks trying to cut off the British from the riverside. They also constantly pressed the Poles. Several tanks from the 30th Corps made it through, but were soon beaten off. The Canadians soon arrived that evening, and their engineer troops managed to make another crossing available, and some 150 troops crossed the river that evening. The 30th Corps later on sent a unit of Guards Armored to re-take the road the Germans already controlled some 20km south of Arnhem. By the 24th of September yet another German force attacked the road, this time to the south of Veghel. Several units were in the area, but were unable to stop them, and the Germans quickly set up defensive positions for the night. It was not clear to the Allies at this point how much of a danger these actions represented. But it was on this day that the operation was essentially stopped and the decision made to go over to the defense. The 1st Airborne, or what remained of them, would be withdrawn that night. The lines would then be solidified where they were, with the new front line in Nijmegen. At 10pm the withdrawal of the remains of the 1st began, as British and Canadian engineer units ferried the troops across the Rhine, covered by the Polish 3rd Parachute Battalion on the north bank. By early the next morning they had withdrawn some 2000 of them, but another 300 were still on the north at first light when German fire stopped the effort. They surrendered. Of the 10,000 troops of the 1st Airborne Division, only 2,000 escaped. To the south, the newly arrived 50th Infantry attacked the Germans holding the highway. By the next day they had been surrounded and their resistance ended. The corridor was now secure, but with nowhere to go.

The operation Marketgarden had ended with some 13,000 Nazi soldiers killed in action, 6,484 British soldiers lost their lives, 851 were missing in action, and 6,450 were taken as prisoners of war. 3,542 American soldiers lost their lives in combat, and the Poles lost 378 men. The figures were devastating, for both the Allies and the Germans, but at the end the objective of the operation Marketgarden was not achieved, and a withdraw had to be made of what was left of the Allied forces. The Dutch also lost several soldiers, so did the resistance, and also a few citizens lost their lives in fighting. Eisenhower believed until his death that Market Garden was a campaign that was worth waging. Had the Nijmegen bridge been taken by the Germans, the British would be cut off, and there would be no chance of saving them, but even with that bridge in the hands of the Allies, if the Germans had captured the Arnhem bridge there would be no hope for them what so ever. Also for much of the road's length the road was a single-track raised ditch, liable to ambush and ensuing congestion. It is surprising in retrospect that the plans placed so little emphasis on capturing the important bridges immediately with forces dropped right on them. In the case of Veghel and Grave, where this was done, the bridges were captured with only a few shots being fired. The same would probably go with the Nijmegen and Arnhem bridge. Although Frost's force was likely doomed, Arnhem was not the only available crossing. In fact, there was a ferry available at Driel. At a minimum, had 30th Corps pushed north, they would have arrived at the south end and secured it, leaving the way open for another crossing to the north at some other point. The commander of 30th Corps asked for another course of action. About 25km to the west of the action was another bridge similar to Arnhem, at Rhenen, which he predicted was undefended due to all efforts being directed on Oosterbeek. This was in fact the case, but the Corps were never authorized to take the bridge. By this time it appears that Montgomery was more concerned with the ongoing German assaults on Market Garden's lengthy 'tail'. Those who suffered the most after the retreat of the Allied forces were the Dutch citizens, who soon found them selves under German controle. Perhaps if the Dutch intelligence was taken more seriously the course of actions would have been quite different. As things turned out, the simple knowledge of the Driel ferry, or of the Undeground's secret telephone network could have changed the outcome of the operation.

In the end Montgomery still called Market Garden "90% successful" and said: In my prejudiced view, if the operation had been properly backed from its inception, and given the aircraft, ground forces, and administrative resources necessary for the job, it would have succeeded in spite of my mistakes, or the adverse weather, or the presence of the 2nd SS Panzer Corps in the Arnhem area. I remain Market Garden's unrepentant advocate. But the Dutch Prince Bernhard said aftewards: My country can never again afford the luxury of another Montgomery success.

The fact still remains that the Operation Marketgarden failed, but the lives of brave young men who fought together for the freedom of Europe, and a faster end to the miseries of the Oppressed European citizens can not be ignored, and the ultimate sacrifice they made can not be forgotten. They fought for all of us, and not only the generations that lived at that time, and it is generations that came after them, generations like mine, and other generations that are yet to come that need to remember their sacrifice, and not let the names of those brave young men, some who even just came out of boyhood be forgotten.

Web site made by Igor Radisic from Belgrade, Serbia & Montenegro. E-mail: [email protected]

60 years later... D-day | Bloody city... Stalingrad | Blue grave... Pearl Harbor | Dust in the wind... El Alamein | Horrific thunder... Kursk

© Copyright protected. All rights reserved. Igor Radisic 2004 - 2005