Iakov Levi

Caravaggio and La Madonna del Serpente*

Oct.20, 2003

Most successful sublimations are, of course, part and parcel of cultural trends and become unrecognizable as sexual derivatives. (Erik.H. Erikson, Childhood and Society).

True, some sexual energy can and must be sublimated; society depends on it. Therefore, by all means, render unto society that which is society’; but first render unto the child that libidinal vitality which makes worth-while sublimations possible. (Erik.H. Erikson, Childhood and Society).

What the father hath hid cometh out in the son;

and often have I found in the son the father's revealed secret.

This outstanding work of art shows a little

child treading on a snake. His mother’s foot is between the child’s

and the snake, so that the child is treading on it and on the serpent.

The Virgin's foot, which interposes between the child’s

and the reptile supports the representation through a repetition. The mother’s

foot is a repetition of the serpent. As Freud has shown in "Symbolism in Dreams" (1915-17), hands and feet are penis' substitutes.

As the Virgin's foot is a repetition of the snake, so

Saint Anne, the grand - mother, is a repetition of the Virgin, confirming

that the child's anal sadistic libido is directed at the mother. After

all, a grand - mother a "twice - mother".

The language of the composition, where the Virgin's foot

and the snake are compressed in the lowest part of the painting, while

the women counter - point (one above the other) the energies that are discharging

from the upper side into the lower, confirms the equivalence between the

two parts.

And the revealed secret, as mentioned in our opening citation

from Nietzsche?

Are not every revelation, secret, and mystery a hint to

the mysterious missing female penis?

As I have sustained in Why is the Lady so Sexy?, the serpent

is the symbol of the fantasized missing female penis (1)

.

Therefore, the child is treading on his mother's penis.

In works of art, as in dreams, the representation is always the outcome of a condensation. In our case, the image condenses the anal sadistic drive of the child and the object of the drive: the mother.

In dreams, repetitions stand for affirmation. As is said in the Bible: "Then Joseph said to Pharaoh, 'The dream of Pharaoh is one ...The dream was doubled to Pharaoh, because the thing is established by God, and God will shortly bring it to pass' " ( Gen. 41:25-32).

And with the words of Theodor Reik: "the unconscious behaves like the ancient languages. Both express the importance and significance of a process by means of repetition" ("The Puberty Rites of Savages", in Ritual. Psychoanalytic Studies, Farrar, Straus & Co., New York 1946, p.140).

Both, serpent and foot, like Oedipus feet, are a displacement

of the penis.

Treading, like every locomotor - muscle activity is the

acting out of an anal sadistic drive (2).

Henceforth, the child is treading on the mother's penis

as synonymous of castration, through a regression to the anal sadistic

level of psycho - sexual evolution, in the same way as clitoridectomy is acted out on virgins in many

African and Asian countries.

That we are dealing with a regression from the genital

level is expressed by the penis pointing at the snake, hinting at

the direction of the libidinal flux discharging through the left leg into

the reptile, and by the nervous tension of the muscles.

The double representation of the missing female penis,

foot and serpent, matches its equivalence in the double representation

of the woman as Virgin and as Mother.

Through repetition, a concept asserts its meaning.

With the words of Nietzsche:

It is good to repeat oneself and thus bestow

on a thing a right and a left foot [as in the painting above]. Truth may

be able to stand on one leg; but with two it can walk and get around (Human,

All-Too-Human II, 13, "The Wanderer & His Shadow")

Art relieves the sufferance inherent in the energetic accumulation

of the repression. As Freud has shown, the pleasure

consists in a reduction of the accumulated tension generated by the unpleasure:

Sensations of a pleasurable nature have not anything inherently impelling about them, wehereas unpleasurable ones have it in the highest degree. The latter impel towards change, towards discharge, and that is why we interpret unpleasure as implying a heightening and pleasure a lowering of energetic cathexis (The Ego and the Id, II)

Dealing with art Freud wrote:

art offers substitutive satisfactions for the oldest and still most deeply felt cultural renunciations, and for that reason it serves as nothing else does to reconcile a man to the sacrifices he has made on behalf of civilization ("The Future of an Illusion" (1927), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, The Hogarth Press, London 1953, Vol. 21, p.14).

In Civilization and its Discontents (1930), speaking of the artist, Freud says:

Another technique for fending off suffering is the employment of the displacements of libido which our mental apparatus permits of and through which its function gains so much in flexibility. The task here is that of shifting the instinctual aims in such a way that they cannot come up against frustration from the external world. In this, sublimation of the instincts lends its assistance (in op.cit. p.79).

And, of course, the artist himself knows best:

At its best, art can be nothing more than a means of forgetting the human disaster for a while (Isaac Bashevis Singer)

The Oeuvre d'art penetrates us without passing through

consciousness, and relieves the sufferance discharging the tension of the

repressed drive, in our case an anal sadistic urge.

The tension is expressed by the contracted face of the

child and by his determined and nervous legs. In art, the language is the

vehicle of the drive's energies.

Of the serpent is written: "Now the serpent was more subtle than any animal of the field which Yahweh God had made

(Gen. 3:1). "More subtle", or "craftier - wiser" as it is sometimes translated, is a wrong translation from the Hebrew 'Arum. The original meaning of the word 'Arum is "naked". Only later it acquired also the meaning of "astute" - "wise".

When we have a double meaning of a word, the more concrete

is the original, and the more abstract meaning is the later overlay.

Therefore, the right translation of the Biblical verse

is: "Now, the serpent was more naked than all the beasts of the field which

the Lord had made"

The serpent is naked, and as such also astute, undecoded, and mysterious like the female genital.

The revealed secret, as hinted by Nietzsche and expressed

by Caravaggio's painting.

The child in the painting is equivalent of the young

heroes of Greek mythology, Ovidius' Apollo, Heracles, Perseus, Theseus,

and even Saint George, who must defeat a female phallic monster, serpent

or dragon, in order to be able to overcome their initiation rite.

Caravaggio's painting is a flash from a segment of their

initiation saga, in which the woman's defeat - and the defeat of her scaring missing penis in order to be able of acting out genital penetration (possessing the woman) -

are acted out through a regression to the anal sadistic level.

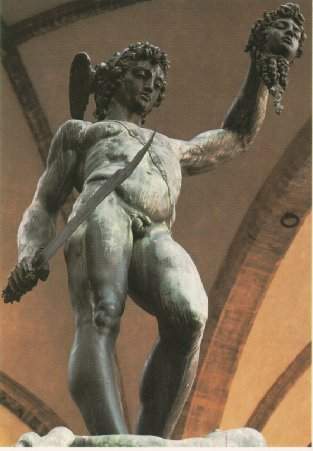

La Madonna del serpente is equivalent to Cellini's Perseus:

a young hero beheading Medusa, whose hair - snakes represent a displacement

from the pubic hair (more precisely, from the fantasized female penis) into the head (S.Freud, Medusa's Head 1940; Sandor Ferenczi, Zur Symbolik des Medusenhaupts, 1923). Moreover, as Freud has sustained in Medusa's Head, beheading is equivalent to castrating.

...And...is equivalent to Saint Michael (or Saint George) killing the dragon.

=

=

Arnold Böcklin:

"Die Pest"

1898 : The female penis as a serpent (a flying dragon) and as a plague.

Women and Their Snakes

Links:

Caravaggio and the Deposizione nel sepolcro

Caravaggio, Clitorectomy and the Talion of the Woman

Soccer Games and Caravaggio

Medusa, the Female Genital and the Nazis

Why is the Lady so Sexy?

Three Women: the Penis

* My thanks to Chiara Lespérance for suggesting to my attention Caravaggio's painting.

(1)

Freud says that the serpent is one of the "less understood" male phallic symbols. ("Introductory Lectures on Psycho - Analysis; Symbolism in Dreams", 1915 - 1917, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, Ed. and Trans. J. Strachey, Hogarth Press, London 1964, Vol.XV, pp.149-155).

Although Freud defines the snake as a male phallic symbol, he was induced into error by the fact, as he himself says, that the woman is fantasized having a penis similar to the masculine one ("The History of an Infantile Neurosis", in op.cit., Vol.XVII, pp.121-2).

Therefore, we should not wonder if there is some confusion on the substance of the female penis, as the child himself is very confused on this issue.

In a letter to Fliess dated the 26th July 1904 he says: “Until now I did not know what I learned from your letter-that you are using [the idea of] persistent bisexuality in your treatments. We talked about it for the first time in Nuremberg while I was still lying in bed, and you told me the case history of the woman who had dreams of gigantic snakes. At that time you were quite impressed by the idea that undercurrents in a woman might stem from the masculine part of her psyche.” (The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Fliess 1887-1904, Translated by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson,The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge – Massachusetts, and London-England, 1995, p.465)

Therefore, Freud had unconsciously perceived that the right association is "serpent = phallic masculine part of the woman", namely, the clitoris as pre- vaginal phallic stage. If he had interpreted the snake as a male penis he would not have raised the question of ambisexuality in this context, and he would have interpreted the dream of the woman as a desire for the male penis.

In one of his last works, published posthumous, Freud hinted that he was close to draw the right conclusion:

The terror of the Medusa is thus a terror of castration that is linked to the sight of something. The hair upon the Medusa's head is frequently represented in works of art in the form of snakes, and these once again are derived from the castration complex. It is a remarkable fact that however frightening they may be in themselves, they nevertheless serve as a mitigation of the horror, for they replace the penis, the absence of which is the cause of the horror. This is a confirmation of the technical rule according to which a multiplication of penis symbols signifies castration (Medusa's Head, 1940).

The snakes are placed on Medusa's head. Therefore, they are the representation of her penis, and not that of the male.

Furthermore, dealing with the theme of the "Taboo of Virginity", where he exposited the psychic danger to a couple where the man firstly deflowers the female, Freud writes:

A comedy by Anzengruber shows how a simple peasant lad is deterred from marryng his intended bride because she is "a wench who'll cost her first his life". For this reason he agrees to her marrying another man and is ready to take her when she is a widow and no longer dangerous. The title of the play, Das Jungferngift ["Virgin's Venom"], reminds us of the habit of snake - charmers, who make poisonous snakes first bite a piece of cloth in order to handle them afterwards without danger ("The Taboo of Virginity", 1918 [1917], in The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, Ed. and Trans. J. Strachey, Hogarth Press, London 1957, Vol.XI, p.206)

Freud's association between snakes first bite and the woman's imene is enlightening.

The significance of the snake as a female phallic symbol becomes clear if we notice that in mythology the reptile is always associated with goddesses and never with gods and heros.

Herodotos knew that the snakes come from Mother Earth

LXXVIII. This was how Croesus reasoned. Meanwhile, snakes began to swarm in the outer part of the city; and when they appeared the horses, leaving their accustomed pasture, devoured them. When Croesus saw this he thought it a portent, and so it was. [2] He at once sent to the homes of the Telmessian interpreters,1 to inquire concerning it; but though his messengers came and learned from the Telmessians what the portent meant, they could not bring back word to Croesus, for he was a prisoner before they could make their voyage back to Sardis. [3] Nonetheless, this was the judgment of the Telmessians: that Croesus must expect a foreign army to attack his country, and that when it came, it would subjugate the inhabitants of the land: for the snake, they said, was the offspring of the land, but the horse was an enemy and a foreigner. This was the answer which the Telmessians gave Croesus, knowing as yet nothing of the fate of Sardis and of the king himself; but when they gave it, Croesus was already taken (Hist., I:78, Ed. A.D.Godley).

"the snake, they said, was the offspring of the land, but the horse was an enemy and a foreigner".

Meaning, the snake is a phallic symbol and an offspring of the Land, herself the symbol of the Mother. It comes from her, it is her penis.

The horse, instead, is an enemy. He comes from outside. Meaning, he is a male phallic symbol, an outsider, like the masculine penis, which is outside and strives to penetrate her. Like the Troian horse, which deflowered the city.

The same concept of the Serpent as phallic symbol of Mother Earth is found in Ovid's, Metamorphoses.

After the Deluge, Mother Earth generates from inside herself an enormous serpent (the Python).

But of new monsters, Earth created more.

Unwillingly, but yet she brought to light

Thee, Python too, the wondring world to fright,

And the new nations, with so dire a sight:

So monstrous was his bulk, so large a space

Did his vast body, and long train embrace. (Metam., I: 435 - 445, Transl. by Sir Samuel Garth, John Dryden)

(2) For muscle erotism, and for

locomotor anxiety as defence from anal - locomotor erotism triggered by the regression from the genital level, see: Karl Abraham, "A Costitutional

Basis of Locomotor Anxiety" ( 1913), in Selected Papers

of Karl Abraham, Translated by D.Bryan and A.Strachey, Hogart Press,

London 1927, pp.234 - 243.