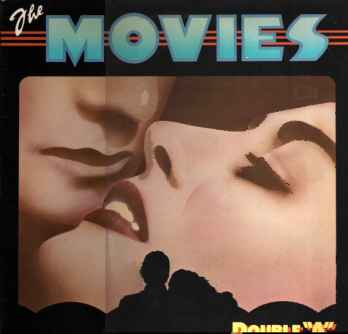

The Movies

Double "A"

and

Bullets

Through the Barrier

Success, particularly in the rock music field, has about as much to do

with chance as it does with talent. A lot of it has to do with being at

the right place at the right time, thus the lucky few “make it,” while

everyone else has to struggle. There are many examples of bands and

artists who aren’t particularly talented, but whom nonetheless scale

heights of fame. Conversely, there are many more examples of bands that

truly did have talent, but due to bad timing, missed opportunities and

what-have-you, never achieved the commercial success they deserved. As

examples of the former are too depressing to contemplate (and yet, too

overly contemplated everywhere else), today I bring myself to discuss

an example of the latter.

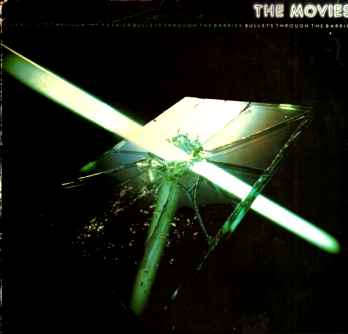

I first discovered Britain’s Movies via their third (1978) album, Bullets

Through The Barrier. I

can’t say particularly what attracted me to the album, but I think it

may have had something to do with the unusual translucent green-white

vinyl on which it was pressed. I wasn’t blown away with it at the time,

but I found it enjoyable enough that I picked up their second album, Double “A”, when I found it some

time later. It didn’t impress me nearly as much as its follow-up, and I

shelved it after a scant few cursory listens.

Bringing them back out of the stacks has been a rather revelatory

experience. Double “A”, which

I’d initally found mediocre at best, I now know to be still patchy but

with some stellar high points. Bullets Through The Barrier, which I’d

initially found “good” now strikes me as a borderline classic.

As the Movies’ history seems to have been mired in a lot of confusion

and misinformation, I feel it only right that I set the record straight

before setting off on my review proper. The band had its roots in the

Cambridge progressive rock band Public Foot The Roman, who had released

one album in 1973 on Capitol/Sovereign. PFTR effectively disbanded

after the release of their album, but keyboardist Dag Small, drummer

Jamie Lane and guitarist Greg Knowles soldiered on, reconstituting a

new band featuring singer/guitarist Jon Cole and

percussionist/multi-instrumentalist Julian Diggle from a competing

Cambridge rock band, Thunderbox. Add Venezuelan bass player Durban

Laverde, and the Movies were born.

Almost immediately, the Movies found themselves with a record deal for

A&M. Their self-titled 1975 debut (produced by ex-Vinegar Joe

guitarist Pete Gage) didn’t shift a lot of units, but it created enough

attention in music circles that got them a lot of good gigs right out

of the gate. The first of these was a support/backup gig for

singer-songwriter Joan Armatrading, whose sophomore 1975 release (Back

to the Night) was likewise

produced by Gage. Their association with Armatrading was a lasting one:

Diggle guested on her 1983 album The

Key, while Lane drummed on 1988’s The Shouting Stage.

1975 also brought difficult change to the band. Four members (Lane,

Knowles, Small and Laverde) were in a train crash in Nuneaton. All four

were injured, but they were the lucky ones; many other passengers died.

But Laverde was injured so badly he was unable to continue playing with

the band. His slot in the subsequent tour was filled by newcomer Dave

Quinn.

Though incredibly talented, the Movies never found the success they so

deserved. Part of it may have something to do with the fact that there

was no ready-made audience for their quirky brand of rock & roll,

but a big stumbling block turned out to be plain old bad timing. In the

U.K., the mid-to-late seventies were a bad time for any young rock band

that wasn’t explicitly punk in orientation. And while they were

erroneously introduced as a “British punk band” at a concert in Norway,

they were decidedly un-punk. Which is not to say they were exactly

prog-rock (despite being erroneously billed as such in the occasional

vinyl dealer’s catalogue), though their virtuosic playing and

conceptual nature (“every song is a picture that moves”) were enough to

brand them as “hippies” by the snotty safety-pin set. The fact that

Knowles and keyboard player Mick Parker both sported beards and shaggy

manes probably didn’t help their case any.

They probably could have stood a better chance in the U.S.A., if only

they had acted faster. They were a bit past-peak when their fourth

album, India (made minus

Parker, and with bassist Colin Gibson replacing Quinn), finally arrived

on American shores. And it didn’t help that there was a bit of

confusion between them and an identically named Seattle pop trio, who

released their one and only (self-titled) album on Arista in 1977. And

you can thank Dave Marsh, the idiot from the Rolling Stone Record

Guide, for propagating that smidgen of misinformation.

So, what did they sound like? The Movies started with a base of good

old rock & roll, cried some blues via Cole’s expressive

slide-guitar and the odd harmonica from Diggle, threw in Latin touches

(especially via Diggle’s percussion), jazzy (even fusion-y) accents and

the odd flirtation with funk and mixed well. Some have compared them to

10cc, but the Movies were considerably less arty, less studio-bound and

far more bluesy and stripped-down. Not quite “pub-rock,” but your

Guinness™ would go down pretty smooth to their music. Some have

inaccurately pegged their music as “new wave,” probably due in part to

Parker’s occasional helium-fuelled synthesizer work, and probably due

in part to Cole’s looks, which were not dissimilar to Elvis Costello’s.

Double “A” opens with a rather

cool, beat-jazz tinged motive for Wurlitzer piano and fingersnaps,

establishing “Heaven on The Street.” Their bluesy touch is immediately

proclaimed by Jon Cole’s authoritative slide-guitar exhortations.

Still, the tune is intriguingly haunting; they definitely know how to

establish a mood. Cole’s lyrical wit, likewise, is apparent right out

of the gate, with slyly comic couplets like, “What our eyes see no eyes

have seen/Since God made street signs.”

“Yo-Yo” is certainly no less moody. In fact, it’s a lot darker than its

flippant title would portend. As a brief instrumental intro, Mick

Parker solos on electric piano over a midtempo, jazzy, conga-laden

groove. The lyrics are a bit elusive, but seem to suggest some sort of

character study. Just who is this Yo-Yo fellow? He seems rather

chameleonic. Parker contributes a second electric piano solo after a

couple of verses. One more verse, then the tune kicks into high-octane

with a double-time conga break. This leads into a sort of

Latin-inspired nonsense refrain, and a high-energy instrumental section

featuring yet another Wurlitzer solo, an acoustic piano solo and a

great, rolling solo from Julian Diggle on timbales, followed by a

fadeout over a repeat of the refrain section.

The next brace of tunes aren’t as substantial. “True Love Trouble,”

Diggle’s lone compositional contribution (and lead vocal), is an upbeat

funky number with a zigzag disco bass-line and a typical Stan Sulzmann

soprano sax solo. “Rumour” is a bit better, a more or less acoustic

number (save for the background synthesizer solo throughout much of the

song) featuring more witty Cole observations. “Rumour, borne on the

wings of surmise.” It ends with the delightfully ironic couplet: “If I

knew a rumour about rumour/I’d tell it to you.” A drone leads us into…

“Playground Hero,” possibly the most musically interesting tune on the

album. Sustained organ chords grow out of the drone as drums roll and

bass and clean-toned guitar lines skitter about. At last, Diggle’s

congas pitter-patter in establishing the rhythm, the rest of the band

joining in with him in due time. A sort of fusion-like melody appears

on the electric piano a couple of times, joined the next time by

Knowles’ guitar playing in unison. At last the “song” proper begins, in

an unusual verse/chorus/sub-verse format. A repeat of the unison line

leads into another verse/chorus/sub-verse. A couple more repeats of the

unison line bleed into a different melody line linking to a solo

section. Beginning softly, Parker plays a spacy solo on his trusty

Wurlitzer, which over its course grows slightly in intensity as the

band reels it in behind him. A sort of bridge, bearing no musical

relation to the previous verses, follows. At its climactic end, more

repeats of that unison line follow; after a couple of fusion-oid

variations at last ending with a couple of ominous synthesizer drones.

The playground/elementary school imagery in the lyrics is used

ironically; the song really seems to paint a cinematic portrait of

gangster life.

“In The Big Boys’ Band” kicks off the B-side with some particularly

nasty, grungy organ chords and Cole’s slide guitar wailing over the

slow, swinging rhythm. The music builds slowly over the course of the

song, with an interesting brass/woodwind (well, multiple flutes,

anyway) arrangement starting off pianissimo, but gradually crescendoing

to duel with the band over the closing solo section, which features a

nifty guitar-duet between Cole and Knowles. Lyrically, this one’s

probably the most pointed satire of the album, with the Salvation Army

imagery serving as a sort of elliptical allegory to the text’s

condemnation of nepotism among the wealthy and powerful. The top brass

at GTO must have had confidence in the tune, extracting it for a single

release (which, of course, went nowhere).

“Boogaloo” is another funk-oriented throwaway with nonsense lyrics but

a somewhat likable synthesizer/filtered guitar duet. “She’s A

Be-Bopper” is a more enjoyable trifle: a cute, breezy pop number about

a man admiring a virtuosic female jazz saxophonist at a nightclub. It

would have been a heck of a lot more respectable, though (to say

nothing of it becoming more conceptually wonderful), if only they’d

managed to get Barbara Thompson, rather than Ray Warleigh, to play the

sax solo at the end of the song.

“Living The Life” announces itself authoritatively with an infectious,

jangling rhythm guitar part and a foot-stomping rhythm, starting off

with the chorus, then going off into the first verse. The middle eight

(sixteen, more like) features another jazzy electric piano solo from

Parker, then it’s back to the refrain. This time, it’s accompanied by

layers of overdubbed handclaps and some piercing guitar injections from

Knowles, carrying on thusly to the fadeout. I think this would likely

have made a better single than “Big Boys’ Band,” as it’s so

irresistible. And the lyrics, about a younger man’s romance with an

older woman, are enjoyably quirky.

“Chasing Angels” fades in on some celestial, echoey synthesizer sounds.

It’s another eerie, haunting number that gets under your skin, in a

minor key with Jamie Lane’s drums and Diggle’s congas gently rocking

back and forth like a ferry-boat as Cole’s slide-guitar and smoky

vocals add their usual bluesy texture and Parker’s synth swoops over it

all in an ethereal manner. In the bridge section, Knowles adds some

superb, piercing guitar lines. It ends, not on the ascending synth

glissando you would have expected, but in the runoff groove as droning,

swirling synthesizer sounds float on beyond said upward glide. It’s a

fitting ending for such an endearingly quirky band.

Double “A” was pretty clearly

lesser Movies, albeit with obvious standout tracks. Bullets Through

The Barrier is

generally regarded as the classic Movies release. One notable

difference between the two albums has to do with the songwriting. Cole

is collaborating a heck of a lot more with his fellow bandmates, Parker

in particular. The result turned out to be what may be the band’s

strongest set of songs.

A little aside here, as I’d be remiss if I failed to mention the

album’s most annoying feature. Mainly, a little quirk about Cole’s

lyric writing. Somewhere in between Double “A” and this album he seemed

to forget how to conjugate verbs. A typical example, from the beloved

“Nobody Loves An Iceberg”:

So broken-hearted he seek Utopia

But where it is he have no idea

So he get out, he look around a bit

He try to see and understand…

Now imagine an entire album (or close to it) of this, and you

begin to see what

I’m on

about. It’s not just contrived it’s annoying! I don’t know

quite what

Cole was going for this, some sort of “realism”? Perhaps he thought he

was being “cool”? In the end, it’s a minor point, the music stands up

pretty well on its own.

“Last Train” (the first of three Cole/Parker co-writes) kicks off

festivities with a bang, a propulsive rhythm gets us charged. A marimba

(played by Cole) imitates pizzicato violin strings as Parker’s piano

pins down the urgent rhythmic pulse. Parker’s keyboard work is many

ways makes the track, his organ swirls add some superb texture.

Cole’s

lyrics, about a spurned lover sending a bomb to her ex, would have been

controversial had it been released today, but seen in proper context it

was just another quirky story-song from a band that specialized in

them. And the “Bye-bye Pepsi Cola” refrain is totally

infectious.

Parker’s Hammond organ solo totally kicks ass, as does Knowles’ lead

guitar work. It’s pretty obvious we’re talking “single material” here,

and it was indeed released as a single A-side. And it’s criminal that

it went absolutely nowhere. We’re talking “lost rock & roll

classic” here, people!

“No Class” is another funk-rocker, but unlike previous attempts (e.g.:

“Boogaloo”), this one works. In part, this is because of a compellingly

funny set of lyrics (about some youths wrecking a classy hotel),

possibly inspired by the same incident that likewise inspired “Merci

and Bye Bye.” But in part, it’s because this one actually has something

previous attempts lacked: a good hook (provided by Parker’s keys, a

staccato unison part on organ and synth).

“Horror Story” again hangs around a unison hook expressed on Hammond

and synth, but is more of a sprightly pop-rocker featuring some

delicious conga-playing from Diggle and some airy slide-guitar from

Cole. A complexly-chorded solo section features a fine Parker organ

solo. This would probably have made a good third single extract (after

“No Class,” another flop single), but apparently wasn’t considered.

“Berlin,” yet one more tune co-penned by Cole and Parker, is considered

one of the band’s all-time classic tunes, and rightfully so. It starts

out with another spacy intro a la “Playground Hero” or “Chasing

Angels,” then metamorphoses into a slow, mysterious electric piano/bass

groove before exploding into an organ-fronted fanfare. The lyrics,

which hint at an espionage theme and which are pure poetry, are served

well by the eerie musical setting. It’s a deceptively simple song for

the most part, made to sound more dense by its flashy intro, another

jazzy Parker electric piano solo, and heavily layered instrumentation

and effects (including, of all things, some accordion from Diggle).

The explosive obsession continues on Cole’s amusing novelty “Blow It Up

And Start All Over Again.” A whimsical tale of a guy transporting

illegal explosives with a chirpy synthesizer hook and falsetto backing

vocals, it’s probably this tune more than any other that is the genesis

of the 10cc comparisons. The backing vocals do are permeated with a Lol

Creme-esque air, and the lyrics have G&C written all over them. But

beyond that, the similarities end. An explosive ending brings us to…

“Love On The Run,” co-written by Cole and Knowles. This is an all-out,

foot-stomping rocker. Slow-paced but high-energy, it goes over six

minutes but never wears out its welcome. One of those tunes where all

the instruments are cranked to 11, this one’s distinguished by some

great interplay by Cole on slide and Knowles on non-slide guitar,

energetically whirling Hammond from Parker and raunchy blues harmonica

from Diggle. It’s songs like this one that make me regret that I never

had the opportunity to see this band live, they must have put on quite

a show.

Rumour has it that “Nobody Loves An Iceberg” was written in ten

minutes. I don’t know that I believe that, it simply sounds too weirdly

constructed. First, the lyrics are just flat-out bizarre, and second,

the verses and chorus are so unalike, it’s almost like they came from

two different songs. Some may say it’s simply “accidental,” the result

of quick thinking, but it sounds like too much thought went into it for

it to be an accident. The verses are dreamy and searching, unlike

anything one’s accustomed to from these guys, but in keeping with the

maritime theme of the text. The chorus is surging, uneasy rock with an

odd hook played by Diggle on his chromatic harmonica (OK, not exactly

Stevie Wonder, but it works). This is another fan-favourite, mainly

just ‘cause it’s so damned strange. The 10cc parallel can probably be

drawn from this one as well, probably because it’s so hard to compare

to anyone else.

“Vacant Possession” is another funk-rocker, this time allowing some of

the band’s fusion-ish tendencies to burst through. And burst through

they do, right at the beginning, with the cracking fusion-y

instrumental line that’s repeated a couple of times through the piece.

This had to have been a hard song for Cole to sing and for the band to

play, the melody is all over the place and the chord changes are denser

than dense. If you’re not paying attention, you’ll miss how complex

this little number is, and it’ll just sound like an ordinary funk song.

Don’t make that mistake, there’s no solos or anything, but this is a

damned complicated tune!

Closing things out is another high-energy rocker, “Merci and Bye Bye,”

co-composed by Cole and drummer Jamie Lane. Reputedly based on an

actual incident in which the band were ejected from Copenhagen’s Plaza

Hotel, it’s the bluesiest song on the album, with copious slide-guitar

from Cole and harmonica from Diggle. Knowles contributes a suitably

fiery guitar solo to the middle eight. In typical Movies fashion, the

tune is absolutely infectious. If you’re not singing along by the

closing chorus repeat, are you sure the rock & roll spirit is in

you?

I think what appeals to me most about the Movies’ music is its

uncategorizability. Unfortunately, it’s that very uncategorizability

that pretty much doomed them from ever finding an audience. Punks

turned their nose up at them for reasons documented elsewhere. Proggers

turned their nose up at them for deigning to write “songs.” No one else

bothered, they were too busy listening to Rumours, or whatever

else the

record companies told them to buy. This is basically the same reason

we’ll probably never see their albums on CD. The nostalgia audience

isn’t there, there aren’t any hipsters out there retroactively

embracing this and the only ones who still care about them are geeky

record collectors like me. Maybe if Quentin Tarantino had inserted

tunes like “Last Train” into his movies instead of bad Dutch pop songs

the world would be a better place.

I think what makes me feel worst is the realization that a band like

the Movies simply couldn’t exist in today’s musical climate. Everything

has become too polarized; the major record companies only want you if

you’re either screaming, unsubtle hard rock or fluffier-than-fluff

bubblegum.

Anything else is regulated to the world of “indie release,” and the few

“indies” that get any kind of press tend to be either insufferable,

posturing hipsters or pretentious tortured-artiste types (or worse,

both). But it’s nice to remember that once upon a time there existed a

band that, in spite of it all, never forgot that rock & roll first

and foremost should be fun.

Special thanks to Jonny Fun's semi-official Movies Page for some of

the

important historical info.

Search for Movies albums on gemm.com.

Return.