Cornwall was famous for its mining and it is said that a Cornish miner could be found at the bottom of every deep mine in the world, their expertise in hard rock mining being world-renowned.

There was trade in Cornish tin as far back as the Iron Age when the Mediterranean countries, possibly the Phoenicians, used tin in the making of bronze. The trade was a well established when in the 3rd century BC the Romans sought new supplies after their source in Spain failed. In the 18th and 19th century copper mining made Cornwall a world leader, with great wealth wrested from beneath the Cornish ground.

It was Dartmoor that had the greatest source of tin in Europe during the medieval period but Cornwall superseded it later, becoming the chief producer of tin and copper for many centuries.

The tin was combined with copper to make bronze for such things like early bronze weapons and much later for church bells; when combined with lead it became pewter , used in production of items such as platters, tankards and other tableware, something for the households of wealthier merchants and craftsmen.

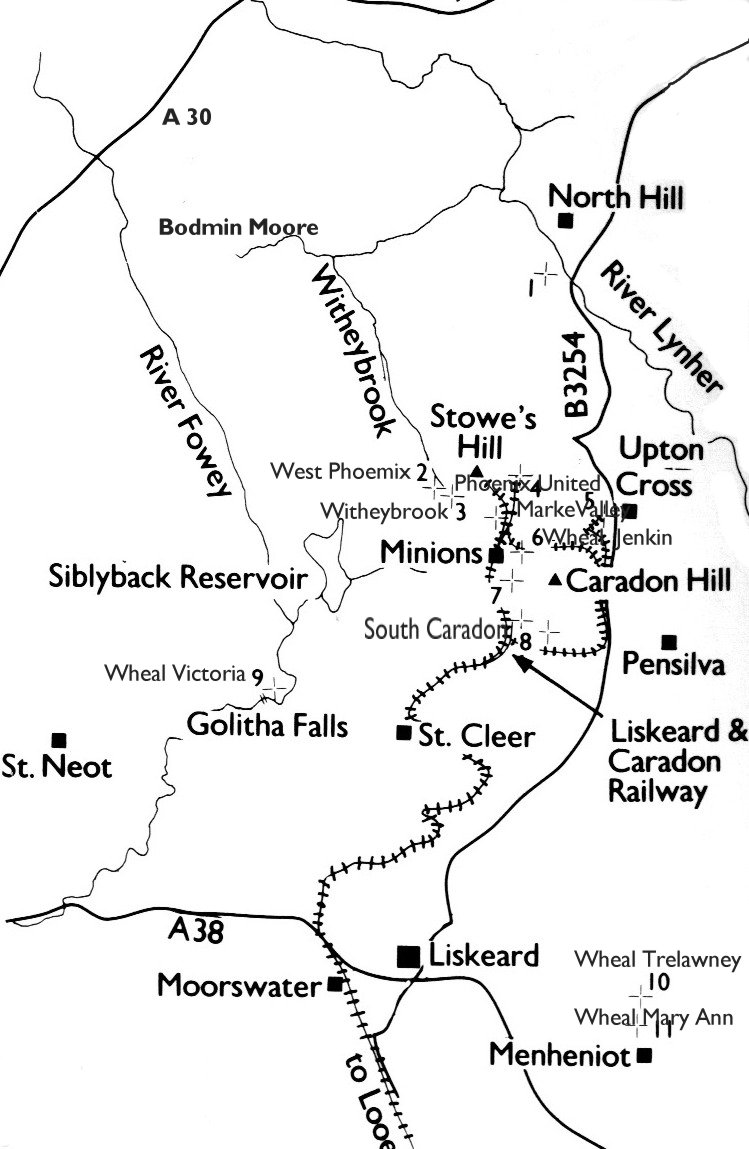

The east of Cornwall was an area filled with mining activity. Centred around Bodmin Moor with the Stannary at Liskeard, Caradon Hill and St Neot close by, this was one of the riches deposits of copper ever discovered and mined during the 19th century. In St Neot there was lead mining and most of the valleys and marshes with filled with the clamour of small workings, which ran up the flanks of the moor. Today you can visit Golitha Falls, along the little road from St Cleer, in a marshy valley running down from the heights of Bodmin Moor you can walk along the river Fowey. The remnants of the mine workings and the remains of the granite wheel pit that held the waterwheel, used to pump water from the shaft in the woods. You can find the leat, a narrow man-made channel, which carried the water to the wheel. Hidden amongst the trees are the shaft and adits, which were small shafts or opening into the mine, but be warned, its dangerous around mine workings and everyone is advised to keep well away. In these now quiet woods copper was mined until it ran out in the 1840-50�s. It�s a spooky place with the rush of the river filling the otherwise quiet air and the trees growing in heavy canopy where men once laboured.

On the coast the small port of Looe was used to export the ores. At first the ores were brought down the valleys on mules. Later a canal brought barges to the coast. Finally a railway was built from Stowes Hill, high on the moor, though Minions and St Cleer down to Moorswater and finally to Looe. Granite, lead, wolfram, tin and copper went out from Looe by sea and the coal needed to power the stream driven mine apparatus was bought in.

Control over mining and miners was exercised by the Stannary Courts and the Stannary Parliament. The Stannary Parliaments met to make new laws or amend old ones and the Stannary Courts metered out its rigorously harsh laws and its brutal punishments The first charters were recorded in 1201 the last coinage in 1838 and the Stannary courts last sat in 1896 although there are still Stannary charters that have never been repealed. In Cornwall Stannary towns were Liskeard, Truro, Lostwithiel and Helston, with Penzance added in 1663. The Stannary towns where places were the tinners brought their smelted ingots of tin to be coyned, assayed and stamped. �Coyning� is the origin of the word �coinage�. A Coyne was the corner of an ingot, which was removed to be tested for purity, before the ingot could be stamped with the seal of the Duchy of Cornwall. Without that stamp of the Duchy the tin could not be sold.

The advent of Newcomens steam pumps improved working in the mines although it was still appallingly dangerous, filthy work. The development that Trevithick made when he introduced the Beam engine allowed the mines delve still deeper into the granite. The buildings that housed the gigantic machinery are why there are ruined engine houses, all across Cornwall, with their chimneys rising from the landscape, ghosts from a previous age.

Some of the Cornish tin mines were very deep indeed, considering the primitive conditions that prevailed. One mine at least had shafts that reached down 550 fathoms, that�s 3,300 feet. In some mine the tunnels and shafts ran for many miles underground, one had 31 miles of underground workings. With wooden ladders and candles, picks, shovels and primitive explosives the miners wrestled huge quantities of ore from the earth, making a few men very rich. In some cases it was the miner themselves received profits because they managed to make investment into the workings. I wonder what they did with that money. Did they have a riotous drunken revel and waste it or did they invest in their future. Certainly there are tales of �Payout Day�, and the miners and their families getting themselves dressed up in their finery. With the large families that were common then it must have made finery for High Days and Sundays quite an expense. The contrast between the hardship and poverty of their daily existence and the sudden �wealth� must have given rise to interesting situations.

The discovery of tin in Australia and alluvial tin in Malaysia brought set backs in Cornwall during the 1860�s and the price of tin fell rapidly. Cheaply produced tin in Bolivia brought the final death knell to tin mining in Cornwall. Copper mining continued but many of the mines struggled and most were closed by 1900. The very last tin mine in Cornwall is South Crofty at Pool. Although closed finally in 1999 it still carries the hopes of its workforce in 2003 and their aspirations that tin mining may rise again in Cornwall. Perhaps they will re name it Phoenix Mine should it ever does work again.