|

CHAPTER1INTRODUCTION |

| Page 5 | Contents |

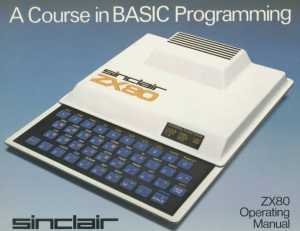

INTRODUCTION – READ CHAPTER TWO FIRST!This book is the user's manual for the ZX-80 personal computer. In it is everything you need to know in order to set up the ZX-80 hardware and to use the ZX-80 BASIC language for writing your own programs. For most of the book the chapters are grouped in pairs. The first (odd-numbered) chapter of a pair is purely descriptive and prepares the reader for what is covered in the second (even-numbered) chapter of the pair. The second chapter of a pair is intended to take you through the use of ZX-80 BASIC as painlessly as possible while you are actually sitting at the keyboard. If you are an experienced BASIC user, you won't need to read very much – probably only chapter 2, the ZX-80 BASIC language summary, and the Index. If you're less experienced and patient, it's probably best to read through the whole book, chapter by chapter. If you're less experienced but impatient you can skip the odd numbered chapters 3, 5, 7, and 9 (and probably will!). OK. NOW READ CHAPTER TWO – AGAIN! |

|

CHAPTER2GETTING STARTED |

| Page 9 | Contents |

GETTING STARTEDThis is the most important chapter in the book. It tells you how to connect up and switch on your ZX-80. The ZX-80 consists of two units:

DON'T PLUG IN TO THE MAINS SUPPLY YET Look at the back of the ZX-80 computer. You will see four sockets. Three of these are 3.5 mm jack sockets marked MIC, EAR and POWER. The fourth is a phono socket for the video cable. The connection diagram shows how to connect up the ZX-80 to the power supply and to a domestic television which will be used to display the output for the ZX-80. A video cable with a coaxial plug at each end is provided to connect the TV to the computer. |

A twin cable with 3.5 mm jack plugs at both ends is provided to connect the ZX-80 to a cassette recorder. Don't worry about this for the moment. Connect the power supply to the ZX-80 by plugging the 3.5 mm jack plug into the socket marked 9V DC IN (if you do get it in the wrong jack socket you won't damage your ZX-80 even if you switch on the power. It won't work until you get the plug in the right socket, though!) SEE DIAGRAM Connect the TV using the coax lead provided. You will have to tune the TV to the ZX-80 frequency, approximately channel 36 on UHF, so check that you can do this – most TV sets either have a continuously variable tuning control or, if they select channels with push-buttons, have separate tuning controls for each channel. If your set is a push-button set select an unused channel (ITV 2, perhaps). Turn down the volume control. OK – we can't put off the moment of truth any longer! |

| Page 10 | Contents |

Connecting up the ZX80 |

|

| Page 11 | Contents |

|

You will be disappointed to see a horrible grey mess on the screen!! Try tuning in the TV set. At some position of the tuning control the screen will suddenly clear. At the bottom left hand corner of the screen you will see a curious symbol – a black square with a white letter K in it. If you can't see the K, turn the brightness control up until you can see it; you may find that adjusting the contrast control improves legibility. You may be planning to use your ZX-80 a lot. If so it may be worth considering buying a second-hand black-and-white TV to use with the ZX-80. They can be bought cheaply – in the UK, at least. STORING PROGRAMS ON TAPEBefore you can store programs on tape you'll have to write a program. The rest of this book is all about writing programs, so the first thing to do is to read on until you've got a program to store... |

The twin coax cable with 3.5 mm jack plugs is used to connect the tape recorder to the ZX-80. Most cassette recorders have 3.5 mm jack sockets for MICROPHONE and EARPIECE. If you have one of those, just connect the 3.5 mm jack plugs as shown in the diagram. On other recorders DIN sockets are used. DIN plug to 3.5 mm jack plug connecting leads are available from most Hi-Fi shops. Consult the handbook to find out how to connect up the plug or plugs. Once you have done this, connect up the cassette recorder to the ZX-80. Set the tone control (if any) to MAXIMUM. Some recorders have separate TREBLE and BASS control. In this case set TREBLE to MAXIMUM, BASS to MINIMUM. Set the volume control to MAXIMUM. Have you got that program? Unplug the MIC or DIN plug from the recorder and use the recorder's microphone to record the program's title; if you haven't recorded your voice saying the program's title, you will have trouble in finding programs when you've got a lot of them on tape. Stop the recorder. Reconnect the plug to the recorder. Get into command mode. Start recording and then type SAVE (E key) and NEWLINE. |

| Page 12 | Contents |

|

The screen will go grey for about 5 seconds, then you'll see a series of horizontal streaks across the screen. After a few seconds the screen will clear and will show the program listing. You will want to check that the program has been SAVED. Unplug the EAR plug. Rewind the tape until you get back to your voice. Now play back. You will hear your title, then you may (or may not) hear a short buzz followed by about 5 seconds of silence. You will then hear a peculiar sound, rather like a supercharged bumble bee. This is the program being played back via the loudspeaker. After a while the sound will change to a loud buzz. Rewind until you are at the beginning of the 5 second silence. Reconnect the EAR plug. Start playing back and then type LOAD (W key) and NEWLINE. The screen will go grey or black and after a few seconds it may start looking grey but agitated. After a few more seconds the screen should clear to show a listing of the program. Note: when you SAVE a program you also SAVE all the data and variables. You can avoid deleting these (RUN clears them) by using the command GO TO 1. |

If it doesn't, use BREAK (SHIFT SPACE) to stop LOADING. If this doesn't work, unplug the power from the ZX-80 for a few seconds. Try repeating the procedure using different volume control settings. If this doesn't work, are you using the cassette recorder on mains power? Try again using battery power. If this fails, check the wiring to MIC and EAR. On the ZX-80 some cassette recorders will not work properly with both jacks plugged in at the same time. You can usually tell if yours is one of these by observing that there is a signal (self oscillation) during the 5 second "silence". To SAVE on these recorders you should connect only from the computer to the cassette recorder external MIC socket. To LOAD connect only from the computer to the cassette recorder EAR socket. Good luck! |

CHAPTER3NOT SO BASIC |

| Page 15 | Contents |

NOT SO BASICNearly all digital computers (such as the ZX-80) talk to themselves in binary codes. We talk to each other in English. This means that either we have to learn binary codes, or we have to teach the computer English. Binary codes are about as difficult to learn as Chinese, but it can be done. Forty years ago you had to learn them if you wanted to use a digital computer at all. But why should we do the work when we've got a computer to do it for us? So we teach the computer English. There is a snag, though. Computers, so far, aren't bright enough to learn English, something which a child of two does relatively easily. This is mainly because we have so many words and ways of saying things in English. A computer would have to learn every single one. We have to compromise half-way between binary and English. Sometimes we compromise at a low level by using assembly codes which are more like binary than English. Sometimes we compromise at a high level by using languages such as ALGOL, PL/1, PASCAL, FORTRAN, and BASIC. These languages are much closer to English than binary. The ZX-80 uses BASIC because it is easy to learn and more than adequate for most purposes. |

BASIC stands for Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code and was devised at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire in 1964 as a simple beginner's programming language. Although it was intended just for beginners, it has since become one of the most widespread and popular high level languages. This isn't very surprising when you think about it, because even scientists and engineers prefer to concentrate on science and engineering instead of trying to talk to computers in complex and difficult languages. Like English, BASIC has a variety of dialects, depending on which computer is being used. The ZX-80 BASIC differs from other BASIC's in some respects. These differences are listed in the appendix "Summary of ZX-BASIC" at the end of this book. As we said before, computers aren't that bright. We have to tell them exactly what to do by giving them a step-by-step list of instructions. This is called a program. Each instruction must be given in a clear and un-ambiguous way – the syntax must be right (in ZX-80 BASIC the computer will tell you if it thinks that the syntax is wrong before you can run the program. Some BASIC's wait until you've tried to run the program before they say "nuts!"). |

| Page 16 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Even if the syntax is right, the computer will be confused if you give it a badly thought out list of instructions. Chapters 5 and 7 give some ideas for making sure that you're telling the computer to do the right things in the right order. STATEMENTS AND COMMANDSZX-80 BASIC allows you to use 22 instructions or statements.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 17 | Contents |

|

There are some normal BASIC statements which are not included in ZX-80 BASIC. These are: Nearly everything that can be done by using these statements can be done in ZX-80 BASIC by using other statements. (The END statement is not needed at all in ZX-80 BASIC). In a BASIC program all statements or lines are preceded by a statement number or line number which labels that particular line. Line numbers can vary between 1 and 9999. The computer carries out, or executes, statements in the order in which they are numbered. It makes life easier by always displaying programs in order of increasing statement numbers, so that the order in which the program is listed is also the order in which it would be executed. |

VARIABLESAll the pieces of information stored in the computer for use in a program are labelled so that the computer can keep track of them. Each piece of information, or variable, has a name. There are two sorts of variable:

Integer variables have names which must always start with a letter and only contain letters and digits. Integer variable names can be any length, so if you wish the name could be a mnemonic for the variable. Some allowable variable names for integer variables are: A A2 AB AB3 ANSWER A4X Y Y8 YZ YZ9 FREDBLOGGS (N.B. no space). AAAA Z123ABC QTOTAL |

| Page 18 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notes:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CHAPTER4TALKING TO THE ZX-80 |

| Page 21 | Contents |

The Keyboard |

|

| Page 22 | Contents |

LET'S TALKSet up the computer as described in chapter 2 and switch on. You will see a THE KEYBOARDIf you look at the keyboard you will see that it looks like a typewriter keyboard but there are some differences. There is no carriage return key (instead there's a key called NEW LINE) and the space bar is replaced by a key labelled SPACE. All the letters are upper case (capitals) so that if you use the SHIFT key you get the symbol printed on the top right hand corner of the key. You'll also notice that quite a lot of keys have labels above them – such as NEW above the Q key. These will save you a lot of time from now on. One vital point: it is very important to distinguish between the letter O and figure 0 or Zero. In the book we will use O to mean letter O and Ø to mean zero. On the screen the computer uses a square O [ |

SINGLE-KEY KEYWORD SYSTEMHit the Q key. Amazing! the computer writes NEW on the screen. Now hit NEWLINE. You have cleared the computer ready to accept a new program. This illustrates the single-key keyword system. Most of the words you'll have to use with ZX-80 BASIC can be typed with only one keystroke in this way. In all this may save you up to 40% of the typing you'd otherwise have to do. Some BASIC's allow you to use single keystrokes to input words like NEW, PRINT, RUN etc but only the ZX-80 prints out the word in full. This makes it much easier to keep track of what's going on in programs. You'll see how it works as you go along. The labels above the numeral keys – NOT, AND, etc – are not keywords. They are called tokens and, when needed, are obtained by using the SHIFT key. This also applies to EDIT on the NEWLINE key. |

| Page 23 | Contents |

|

Getting data in and out of the ZX-80 computer. Type exactly: 1ØO"THIS IS A STRING" That should have come out as The computer provided the word PRINT, as well as the space between the 1Ø and PRINT. Did you notice what happened to the 1Ø PRINT " This |

The Type " and hit the NEWLINE key. The computer accepts the line and displays it at the top of the screen together with a Although there is only one line entered it is a program consisting of only one instruction. Type R (RUN) and NEWLINE and the program will run – after a brief flicker on the screen the words Type any key to get back into command mode. What the computer did was to print all the characters between the quotation marks. Any character (except for quotation marks) is legal when PRINT is used in this way. |

| Page 24 | Contents |

|

In general this form of the PRINT statement is useful for titles which only have to be printed once in a program. There are other forms which allow more complicated things to be done; you'll come across these the whole way through this book. Now let's try getting some data into the computer. This is done by using the INPUT statement, which is basically of the form: Hit NEW (key Q) and NEWLINE. This tells the computer that a new program is being entered. Type in the following program, using NEWLINE at the end of each line. (If you make a mistake, use SHIFT Ø (RUBOUT) to delete the mistake; every time you hit RUBOUT the character, keyword, or token to the left of the cursor is deleted). 1Ø PRINT "ENTER YOUR STRING" 2Ø INPUT A$ (A$ is the name of a string variable) 3Ø PRINT A$ (You can use PRINT to print out a variable) Now run the program by typing RUN (key R) and NEWLINE. |

The computer responds with Type in a short message or random string of letters (don't use quote marks) and press NEWLINE. The computer prints out what you have just put in, which was a string variable called A$. Get back into command mode by pressing any key. Try running the program several times using more and more characters in your string. Keep an eye on the cursor. On the 15th line it will vanish. RUBOUT (shift Ø) – the cursor will reappear. Now carry on adding characters – the display will gradually get SMALLER as you use up the storage capacity of the processor. Now hit NEWLINE – a 4/2Ø error message appears. The 4 tells you that the ZX-80 ran out of space to put the string variable into, and the 2Ø tells you that this happened at line 2Ø of the program. Get back into command mode. |

| Page 25 | Contents |

|

You may have wondered why the line numbers have been 1Ø, 2Ø, 3Ø instead of (say) 1, 2, 3. This is because you may want to add bits to the middle of your program. For instance, enter The program displayed at the top of the screen now reads |

FIRST it asks you for a string. Enter a string. THEN it asks you for a number. Notice that when the ZX-80 is waiting for you to enter a number it displays FINALLY it prints out what you put in. In chapter 3 the difference between string variables and integer variables is mentioned. The program has two variables in it – a string variable A$ and an integer variable A. How does the computer react when you give it a different sort of variable to the one that it's expecting? Easy enough to find out – just run the program again. When the computer asks you for a string, give it a number. What happened? It was accepted – numbers are acceptable inside strings. Now – when it asks you for a number, type in a letter. Nothing much happened except that 2/24 appeared at the lower left hand corner of the screen. This is another error code. The 2 stands for the type of error – VARIABLE NAME NOT FOUND – because the computer knew that the letter was the name of an integer variable and you hadn't assigned a value to it. The 24 stands for the line number at which the error was found. |

| Page 26 | Contents |

EDITING PROGRAMSSuppose that you want to alter something in a program that you've already entered. (This is called editing a program.) It's easy on the ZX-80. Get into command mode. Look at the listing at the top of the screen. The A further key, HOME (SHIFT 9) sets the line pointer to line Ø. Because there isn't a line Ø the cursor will vanish if you use HOME – but when you hit SHIFT 6 the cursor will jump to the next line – in this case line 1Ø – and reappear. Select a line – line 22 for example. Now hit SHIFT NEWLINE. Line 22 (or any other one you might have selected) appears at the bottom of the screen. |

Try SHIFT 8 ( This editing facility is very useful if you want to alter individual characters within lines. However, if you want to delete a whole line it would be rather tedious to go through the procedure mentioned above. There is a simpler way to delete lines, though. Type the line number, then NEWLINE – and you'll see the line vanish from the listing at the top of the screen. The cursor THE LIST COMMANDAs you get more experienced with the ZX-80 you'll want to write programs longer than the 24 lines which will fit onto the screen. This could pose a problem – or could it? We can find out by writing a really long program. Type NEW then NEWLINE. |

| Page 27 | Contents |

|

Enter the following program (which prints a large number of blank lines). We seem to have lost the first few lines. Or have we? Hit LIST (key A) followed by NEWLINE – the program is now displayed from line 1Ø down. Now try LIST 2ØØ – the program is displayed from line 2ØØ. You can list the program starting from any line you want in this way. Notice that the current line cursor is altered to the line you selected. Try using the up/down cursor control keys – go on hitting the |

In this way you can display any part of the program you want. By now you will have realised that the ZX-80 has some powerful (and very convenient) facilities to help you write programs. From now on we can concentrate on how to write programs which actually do something – like solving arithmetic problems, for instance. |

CHAPTER5SO YOU'VE GOT PROBLEMS |

| Page 31 | Contents |

SO YOU'VE GOT PROBLEMSPeople are very good at disentangling confused instructions and solving complex problems. A computer isn't – all it can do is to follow a list of instructions and carry out the instructions as it comes to them. As an example, take the following instructions which a mother might give to her child: "Could you run down to the shop and buy some bread? Take 50p which is in my purse on the kitchen table. And for goodness sake get dressed!" It all seems quite clear; the child knows where to go, what to buy and where the money is. A computer controlled robot would take the first instruction: The second instruction: buy some bread. It can't do that (no money) and at this stage would probably just stop, baffled. The third instruction: take 50p from the purse, it can't do that. The fourth instruction: go to the kitchen table. It returns home and goes to the kitchen table. |

Then the fifth instruction: get dressed. A child would instinctively carry out the instructions in the following order:

He or she would come back home! The mother in this example missed out one vital instruction ("come home") as well as putting the instructions in an illogical order. Children use commonsense to interpret complex instructions, but computers can't do this. You have to do all the thinking in advance when you use a computer. So remember: THINK STRAIGHT One way of making sure that you are thinking straight is by drawing a flow diagram before you start to do any actual programming. This helps you get things in the right order to begin with. |

| Page 32 | Contents |

|

The flow diagram for the example above would look like this:  Each box contains an instruction, and the arrows show the order in which the instructions are executed. Well, that looks pretty simple and neat. Now that the flow diagram is drawn on paper we can check it by going through the boxes one by one and asking ourselves: Can the child (or the computer) do this? Starting with the first box (get dressed) we might think that it's pretty basic. On the other hand, the child may not be able to find his clothes because his naughty sister has thrown them out of the bedroom window. Perhaps we should add an instruction (find clothes) at the beginning of the program. |

Go to the kitchen table: well, that looks OK. Take 50p from purse: what happens if the purse is empty? Go to the shop: does the child know where the shop is? Buy some bread: what sort? Return home: nothing much wrong with that! Maybe the flow diagram wasn't as good as we thought. Even simple tasks can turn out to be more complicated than we think. Most of the problems which we've spotted are due to a lack of information and this can be coped with by adding extra instructions at the beginning of the program. These could include:

When you are writing programs for the ZX-80 it is particularly important to give the computer all the information it needs before it has to carry out a task. For instance, if you ask it to PRINT a variable the computer must know the value of the variable. Now for some arithmetic. |

CHAPTER6FINDING THE ANSWERS |

| Page 35 | Contents | ||||||||

FINDING THE ANSWERSUp to now you've just been getting used to the feel of the computer. Now we'll actually use the computer to do a few sums. THE LET STATEMENTNearly all arithmetic operations are done by using the LET statement. It is of the form In this case the variable (which can have any name you assign to it) is what you want to find out. The expression describes how you want to define the variable. For instance You can use other variables: |

One condition: the computer must already know what the values of B and C are before it comes to the LET statement. The equal sign (=) isn't used in quite the same way it is in ordinary arithmetic or algebra. For instance: Obviously J isn't equal to J+1. What the LET statement means is: The + sign is called an operator and defines the operation you wish to be performed. The other arithmetic operators are:

Here is a program for multiplying two numbers together |

| Page 36 | Contents | |||||||||||||||

|

3Ø INPUT A Notice LINE 7Ø. It's a PRINT statement with a string between inverted commas, but it's got a C added to it. This form allows you to economize on PRINT statements. Enter the program and try running it, using two quite small numbers – such as 17 and 25. The computer will come up with the answer: Run the program a few more times, increasing the size of the input variables. At about 255 x 129 or just a bit larger you will get another error message – 6/60. The 6 is the code for arithmetic overflow because the answer is larger than 32767, which is the largest number the computer can hold as an integer variable. Now try editing the program so that it does addition instead – just change the * to a + in line 6Ø. You can also try subtraction and check that you get negative numbers when A is less than B. |

All fairly straightforward so far. Shouldn't that be 1.5? Well, yes, but the ZX-80 uses integer arithmetic – only whole numbers can be expressed. What the computer does is to do a division normally and then truncate the result towards ZERO. As examples:

This means that you may have to be careful when you use division – it's always fairly accurate when you're dividing a large number by a small number, but may be less accurate when the two numbers are closer together in size. |

|||||||||||||||

| Page 37 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Luckily there are ways of getting round this problem. For instance, here is a program which will give quotients to 3 decimal places using integer arithmetic only.

|

This program does a long division in exactly the same way as we would do it on paper. Notice the PRINT list in line 13Ø – it contains several literal strings and variables separated by semicolons. The semicolons tell the ZX-80 that each thing to be printed must be printed immediately after the preceding item, without spaces between them. Also notice the LET statements from line 7Ø on. There's no fiddle – you can use more than one operator per statement. There is a snag, though. Operations are not necessarily carried out in order from left-to-right. The order in which they are carried out depends on what sort of operations are present in the statement. Here is a list of priorities for arithmetic operations:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 38 | Contents | ||||||||||

|

Now for some experiments Try running this with A=1, B=2, C=3 but before you start, use the priority rules to predict what answer the ZX-80 will give: 7 or 9? O.K. – run it now. The answer was 7. First the computer multiplied 2 by 3 to get 6, then it added 1 to get the final answer. Try a few other combinations by editing statement 8Ø – like

|

Here's a golden rule; when in doubt either use more than one LET statement and build up that way, or use brackets. Brackets make life much easier when it comes to complex arithmetic operations. Take example Z=A/B*C The normal sequence would be for the computer to evaluate B times C and then divide A by the result. If we put brackets round A/B thus: A more subtle example is: At first sight you would think that these would give the same answer. Well, they do – sometimes! |

| Page 39 | Contents |

|

Try them both using A=100, B=25, C=5 (the answer is 5ØØ). Now try it both ways using A=100, B=3, C=5 (the answer should be 6Ø). What happened when you used the brackets? Think about it. The phantom truncator has struck again! The computer evaluated 3/5 first and truncated it to ZERO – then it multiplied 1ØØ by ZERO and naturally got ZERO as a result. All this emphasizes that you have to be very much on the alert when you use integer arithmetic for multiplication and division. Multiplications can cause arithmetic overflow problems (which will cause the program to stop), whilst small numbers used in division may give rise to funny answers which don't give error codes. If you think that you're going to run into truncation then do multiplications first – on the other hand it may be better to do divisions first to avoid overflow. That's probably enough arithmetic for now. Let's move on to more interesting things. |

CHAPTER7DECISIONS, DECISIONS |

| Page 43 | Contents |

DECISIONS, DECISIONSSo far we have only considered problems which can be solved by carrying out a list of instructions, starting at the beginning of the list and working steadily down the list until the last instruction is carried out. The next four chapters deal with ways in which you can make the ZX-80 (or any computer using BASIC) carry out much more complex programs which can perform many tedious tasks. In chapter 5 we talked briefly of the use of flowcharts for checking that the program steps were in a logical sequence. This can be useful even for simple programs. When it comes to complex programs flowcharts are vital. Let's consider a problem we face every day – getting up in the morning. There is a flowchart for getting up on the next page. The program is said to branch at each decision diamond. As you can see, one feature of branches is that they allow some parts of the program to be skipped if they are not necessary. Programs can get difficult to understand if there are a lot of branches, and this is where flow diagrams can help. |

It is a good idea to keep a pad or notebook handy when you are writing programs and an even better one to draw a flow diagram of your program before you start writing it! Turn to the next chapter to find out how the ZX-80 can take decisions. |

| Page 44 | Contents |

|

|

CHAPTER8BRANCHING OUT |

| Page 47 | Contents |

BRANCHING OUTBefore we go on to real decisions let's have a look at the GO TO statement. This is of the form When the ZX-80 comes to a GO TO statement it jumps straight to statement number n and executes that statement. If n is a variable – X, say – the computer will look at the value of X and jump to the statement with that number – assuming that there is a statement with that number in your program. A further refinement of the GO TO statement is that n can be any integer expression such as A/1Ø. Here again, this is possible with the ZX-80. Here is a program which illustrates the use of GO TO. |

The computer responded with It skipped statement 3Ø. "That's not much use", you must be saying, "what's the point of including a perfectly good statement which will never be executed?" OK Now, type GO TO 3Ø, and then NEWLINE. The ZX-80 came back with This demonstrates two uses of GO TO – first to jump unconditionally to an arbitrary statement (in this case statement 4Ø); second as a command which causes the computer to jump to the desired statement (in this case 3Ø) and start executing the program from there. |

| Page 48 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

THE IF STATEMENTThis is the most powerful control statement in BASIC. It allows the user to incorporate decision-making into his programs. Here is a program for calculating square roots approximately. It does this by multiplying, a number by itself, starting with Ø and comparing the result with the number whose square root is to be found. If the product is less than the number to be rooted it increases the number by 1 and tries again.

|

See the diagram on the next page. The form of the IF statement is: In line 7Ø the condition to be met was D=Ø and if this is so then J is exactly the square root of X, so we want to print THE ROOT IS J. In this case (DO THIS) is GO TO 11Ø which is the number of the PRINT statement we want. In most BASIC's the only thing you can do in an IF statement is to GO TO a line number. The ZX-80 lets you do other things as well. In fact it lets you do almost anything! Some examples: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 49 | Contents |

|

|

| Page 50 | Contents | ||||||||||||||

|

Any keyword can follow THEN in an IF statement – even things like LIST or RUN. The results can be rather peculiar if you use commands such as LIST. The examples listed above can be useful, though. The condition to be met is (in its simplest version) of the form: A relational operator can be:

In these cases, A, 2, 1Ø, A+B and C+D are the expressions. The expressions need not be a simple integer or integer variable. The statement IF A = Z - (Z/B) * B THEN GO TO 1Ø |

The condition to be met can be even more complex because logical operators can be used. For example This NOT operator negates the succeeding condition, so that the ZX-80 will jump to 1ØØ if A does not equal 2. This program illustrates the use of the AND operator. The condition to be met is that ALL three variables must be 1; if this is so it will print OK. You can chain together as many conditions as you like in this way. Try running this program and see if you can make it print OK in any way other than by entering three 1's. |

||||||||||||||

| Page 51 | Contents | ||||||

|

The other logical operator is the OR operator. Edit the program by changing the AND's to OR's (OR is SHIFT B). When you run the program now you will find that it prints OK as long as one of the numbers entered is a 1. You can use brackets to group things together.

If you remember, in chapter 6 we said that some operators had priority over others – multiplications were carried out before divisions or additions, for instance. The same applies to logical operators. Their priority (in descending order) is |

Thus, in (a) B=1 and C=1 is taken first, so that the computer will print OK if B AND C are 1 but will also print OK if A=1. The brackets in (b) work in the same way as they did for arithmetic operators. Thus the ZX-80 will print OK if C=1 and either B=1 or A=1. The operators NOT, AND and OR also allow you to produce conditional expressions. For example, if you require

The obvious way is: However you could instead write: To round off this chapter on branching, here is a program which throws a die. The program uses a useful facility, the function |

| Page 52 | Contents |

|

1Ø PRINT "DIE THROWING" 2ØØ PRINT E$ |

3ØØ PRINT C$ 4ØØ PRINT D$ 5ØØ PRINT A$ 6ØØ PRINT A$ |

| Page 53 | Contents |

|

7ØØ PRINT A$ It's a bit of a strain to enter this program but it's quite fun to run. Note that lines 14Ø to 19Ø could have been replaced by If you want to make the program restart itself try editing the program: |

|

| Page 54 | Contents |

|

Two points: CLS clears the screen. If you didn't put this in the screen would fill up after 3 goes and the program would stop, giving an error message such as 5/3Ø5 (run out of screen at line 3Ø5). Secondly, the use of an INPUT statement to halt program execution is a useful trick. The string variable X$ is used in statement 13ØØ when it is tested to see that only NEWLINE has been pressed; any other entry will stop the program. (There is nothing between the quotation marks in 13ØØ.) The reason that there is an IF statement at 13ØØ rather than a GO TO statement is that, while the ZX-80 is waiting for a string variable to be entered, the BREAK key (SHIFT SPACE) doesn't work. As a result it is difficult to get out of the program except by entering a very long string variable, a variable so long, in fact, that it makes the computer run out of storage space. This is very tedious, so it's better to use the IF statement. Then if you enter any character the program will stop. |

(If you do ever get into a situation when nothing you do seems to have any useful effect on the computer, try the BREAK key first. If this has no effect, give in and switch the ZX-80 off for a few seconds. You lose the current program, but this may be inevitable if you really have got yourself into a fix.) |

CHAPTER9ITER – WHAT? |

| Page 57 | Contents |

ITER – WHAT?Very often we come up against problems which involve repeated operations. The square rooting program in chapter 8 was one example of such a problem, and the program was written so that the computer jumped back to line 5Ø, if the test conditions in statements 7Ø or 8Ø were not met, and tried again – and again – until the conditions were met. Programs of this sort are called iterative. By using iterative techniques it's possible to get the computer to do a lot of work with a very short program. It's easy to make a program iterative – all you have to do is to put a GO TO statement at the end of the program to jump the computer back to the first statement (or any other suitable statement). One snag is that such iterative programs can get stuck in endless loops. One way to avoid this is to allow the computer to go round only a set number of times. One way of doing this would be to use IF and GO TO statements. Consider the following program which prints $ 152 times. |

First the program sets J (the loop control variable) to 1. Then it prints $. Then it tests to see if J=152. It isn't and so the computer goes on to line 4Ø which increments the value of J by 1 to 2. The computer passes on to 5Ø which tells it to jump back to 2Ø. This process goes on until J=152 when the IF statement is satisfied and the computer jumps out of the loop to line 6Ø. The arrows on the program help you to see where the program is going; for short programs this is quicker than drawing a flow diagram and does make it easier to see what the program is doing. The program took 5 lines (if you don't count the STOP statement, which doesn't actually do anything, it just serves as a target for the GO TO in line 3Ø). Loops are so useful that you'd have thought that there was an easier way of writing programs using them. Well there is. Turn to chapter 10. |

CHAPTER10LOOPING THE LOOP |

| Page 61 | Contents |

LOOPING THE LOOPBecause loops are so useful some special statements have been devised to make it easy to use them. Program for printing $: In chapter 9 it took 5 lines of program to get the same result using IF and GO TO statements. Note the ; after the PRINT statement. This tells the computer to print each $ immediately after its predecessor. Try running this program. It's a pity that one can't have a dollar bill for each $ sign printed. In BASIC these loops are normally called FOR loops. They are also widely known as DO loops (because other languages, such as FORTRAN, use DO instead of FOR). There is nothing to stop us from putting a loop inside another loop – or putting several loops in: |

Add the following lines to the program:

|

| Page 62 | Contents |

|

You can jump out of a loop at any time. If you do this the loop control variable will remain at whatever value it had got to when you jumped out. In our case the loop control variables were J for the major loop and I for the minor loop. Try jumping out of the major loop at J = 1ØØ Run this. You'll see that you get fewer $'s and £'s. Get into command mode. This shows two things

If the loop is completed successfully for all values of J up to 152 (in this case) the control variable will be left at 153. This is because the NEXT J statement not only tests the value of J but also increments J by 1. |

Some BASIC's allow you to increment the control variable by other amounts, but this isn't possible on the ZX-80 (It's not a very useful feature anyway.) All this is quite straightforward. NEXT J reminds the computer that it is in a loop and tells it what variable it should be testing and (in fact) where it should jump back to if the loop isn't finished. You can start at any value you like – try starting at J=1ØØ. The computer will go round the loop M - N + 1 times. DON'T EVER jump into a loop unless you have just jumped out of it – if you do the computer will skip the FOR statement and will get very confused because it won't know what the control variable is, what it should start at and what it should finish at. It will do the best it can but it will probably stop when it gets to the NEXT statement. The error message will be of the form |

| Page 63 | Contents |

|

1/LINE No. where 1 means "no FOR statement to match this NEXT statement", or 2/LINE No. where 2 means "variable name not found". You can try this by adding to the program: This will jump the ZX-80 into the major loop and it will stop when it gets to statement 6Ø (NEXT J) giving the error message 2/6Ø or 1/6Ø. In chapter 6 there was a program to divide one number by another to give a quotient to 3 decimal places. Here is a program to give any number of decimal places. Statement 1Ø is a remark. The computer disregards REM statements when it executes programs. It's often useful to put comments and remarks into programs so that you can remind yourself what the program does when you look at it, often months later! 1Ø REM HIGH PRECISION DIVISION |

3Ø INPUT D Note line 11Ø |

| Page 64 | Contents |

|

11Ø FOR J=D*1Ø TO D*2ØØ would be quite legal. However, the name of the control variable must be a single letter. If you do decide to use several FOR loops, one inside the other, be very careful in the way you go about it.

On the other hand |

One final point: because the control variable is effectively tested and incremented by the NEXT statement the main part of the loop will always be executed at least once regardless of the value of the control variable even if you have jumped into the loop. SUBROUTINESA subroutine is a sub-program which may be used once or many times by the program (or main program). Example: Statement 2Ø tells the computer to GO TO the subroutine at line 1ØØØ. |

| Page 65 | Contents |

|

This prints: Statement 11ØØ tells the computer that the subroutine is finished and that it should return to the main program. The computer then jumps to the line immediately following the GO SUB statement and executes that (in this case: NEXT J). An example of the use of subroutines is given below: The Chinese Ring Puzzle. As you will see, one subroutine can call another, or even call itself (this is called recursion). THE CHINESE RINGS PUZZLEThis is a program which will say what moves are required to remove N rings from the T-shaped loop. The mechanics of this wire puzzle are not important – roughly speaking one manipulates the rings until they all come off the loop. |

For an arbitrary number of rings the rules are as follows:

To remove the first i rings:

To replace the first i rings:

|

| Page 66 | Contents |

Chinese Ring Puzzle |

|

| Page 67 | Contents | |||||||||||||||

|

CHINESE RINGS (Recursive procedure) 1ØØ IF N<1 THEN RETURN 5ØØ IF N<1 THEN RETURN |

Your output for the case N=4 should look like:

The GO SUB statement can be used in conjunction with a variable, e.g.

In general it is not a very good idea to use variables or expressions in this way because the program may alter the variable in a way you hadn't foreseen and thus cause problems. |

CHAPTER11HOW TO PRINT |

| Page 71 | Contents |

HOW TO PRINTUp to now we have used the PRINT statement as and when it was needed to print out headings and variables. In fact PRINT is a very versatile statement indeed. The general form of the PRINT statement is Expressions can be literal strings in quotes, e.g. Alternatively they can be integer variables or arithmetic expressions, e.g. The object of using control characters is to be able to control the spacing of the line to be printed. We've already come across the use of ; in PRINT statements. |

The program The semi-colon (;) makes the computer print out the expressions without any spaces between them. If you want spaces you have to include them in the literal strings to be printed. The comma (,) is used as a tab. Each display line of 32 characters on the screen is divided into 4 fields each of which is 8 characters in length. Each time the computer comes across a comma in a PRINT statement, it starts printing the next expression at the beginning of the next available field. The effect of this is to provide a display on the screen in 4 columns. If a string or literal string is more than 7 characters long and is followed by a comma the computer uses two or more fields in which to print the string and starts the next expression at the beginning of the third field. |

| Page 72 | Contents |

|

You can add extra commas to skip fields: The statement The computer used 2 fields for the first string, skipped a field and then continued. It runs out of fields on the first line and has to continue in the first field of the second line. There is no limit to the number of fields you may skip using commas, (Unless you run out of display area, of course.) |

If you use a control character right at the end of a PRINT statement the next PRINT statement will obey the control character. For instance If no control character occurs at the end of a line the next PRINT statement will start printing on a new line. The best way of finding out about PRINT is to experiment with it. |

CHAPTER12COPING WITH CHARACTERS |

| Page 75 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

COPING WITH CHARACTERSYou will have noticed that, in addition to the normal typewriter characters there are several other characters not usually found on a typewriter. In addition there are some usable characters not written on the keyboard. Before we go on to investigate what characters can be printed, meet an interesting function:

It is mainly used in conjunction with the PRINT statement. Try this: What this program does is to ask for a number and then to print out the character whose code is the number entered. The codes lie between Ø and 255. A useful program for listing the symbols is given below. |

1Ø PRINT "ENTER CODE VALUE" This lists 11 symbols together with their codes, starting with the code entered at the start of the program. Table of characters corresponding to different codes:

|

| Page 76 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| Page 77 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Inverse means that the character appears white on a black background. The graphics characters are shown on the next page: CHR$(X) allows us to print any character we want. |

There is a further group of facilities which enables us to handle characters; These are (b) CODE(string) An example of the way in which these can be used is the following program which accepts a string and prints it out in inverse video. |

| Page 78 | Contents |

Table of Graphic Symbols |

|

| Page 79 | Contents |

|

4Ø LET X=CODE(G$) Statement: 5Ø adds 128 to the code (this gives inverse of the letters, digits and graphics). 6Ø tests the string to see if it is a null string, i.e. has no characters in it. If it is a null string either the input string was a null string to begin with or all the characters have been converted to inverse video and printed. 7Ø prints the inverse video character. 8Ø chops off the character which has just been printed and the program then jumps back to 4Ø and the code for the next character is extracted. The program goes on until the string has been shortened to the null string. |

There is a further function which can be useful. This allows an integer number or variable to be treated as a string variable. So far we've not said very much about the graphics symbols. These have been designed so as to double the effective resolution of the display, which gives 23 lines of 32 characters each. Here is a program which plots TWO bar charts on the same display. |

| Page 80 | Contents |

BAR CHART PLOTTER 1Ø LET X=Ø 8Ø FOR J=1 TO 2Ø |

12Ø IF J>Y AND J<Z THEN PRINT CHR$(3); 135 PRINT The program prints Z as black bars, Y as grey bars. Statements 8Ø to 13Ø determine what graphic symbol is to be used: This program calculates the graphs of Y = X and Z = 24 - X and plots them in bar chart form. As you will see if you run the program it produces a very clear, unambiguous display. You can use the same sort of trick to achieve greater resolution along the line as well as from line to line. Lines 85 to 125 decide what character will be printed, depending on the relative size of J, Z and Y. These examples are only scratching the surface when it comes to character manipulation and graphics. The possibilities are almost literally endless. |

CHAPTER13HELP! OR, WHAT TO DO WHEN DESPERATE |

| Page 83 | Contents |

HELP! or "What to do when desperate"You may occasionally get into difficulties. These may be divided into two sorts:

Most problems with the system are likely to occur when you're entering string variables into your programs. One favourite is deleting the quotation marks round the string by accident. When the computer is waiting for you to enter a string variable it prints " If you enter the wrong string and then use RUBOUT to delete it you may delete one or other of the quotation marks. This will give rise to a If you have written a program which calls for a null string to be entered, and the program is recursive, you may find it very difficult to get out of the program back into command mode. Whatever you enter seems to have no effect! |

When (or if) this happens delete the quotes using RUBOUT Generally speaking the BREAK key (SHIFT SPACE) is the first thing to resort to. If the program is caught in an endless loop, or if it is LOADing unsuccessfully, the screen will go grey or black for an indefinite period. BREAK will get you back under these conditions. If BREAK does not work in this situation there is nothing left to do but switch the ZX-80 off for a few seconds and then switch on. You do lose whatever program was in the ZX-80 if you do this. When it comes to faults in the program it is difficult to offer such specific advice. Some problems arise if you type an O instead of a Ø. LET J = O would be accepted as a valid program line but it would give a 2/N error code (variable not found) when the program was run. This sort of thing can be very difficult to spot. Similarly S and $ do get confused. |

| Page 84 | Contents |

|

When a program stops unexpectedly or does something peculiar it may be difficult to work out exactly what went wrong. It is possible to carry out a post-mortem by using the immediate PRINT statement to find out what the value of variables (especially loop control variables) was at the time the program stopped. If you type Sometimes there is not room to print the whole of the line number in an error message, particularly with error numbers 4 and 5. In this case usually only the first digit of the line number is printed. For example, error 4 on line 25Ø may cause the message Another useful technique is to put STOP statements into programs at key points. When the program reaches the STOP statement it will stop (of course) and you will be able to see how it has performed up to that point. You can then get back into command mode, type CONTINUE (key T) NEWLINE and the program will continue from the STOP statement. Luckily the ZX-80 is quite choosy about the program lines it will accept and this eliminates many of the problems which can happen with other BASIC's. |

|

CHAPTER14A RAGBAG OF FUNCTIONS |

| Page 87 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A RAGBAG OF FUNCTIONSThis chapter covers all those statements and functions that haven't already been dealt with elsewhere.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 88 | Contents | ||||||

The reason that the variables associated with PEEK and POKE should always be less than 256 (255 is maximum) is that everything in the ZX-80 is stored in 8 bit bytes. Bit is short for Binary digit. The maximum which can be stored in 8 bits is 255, and so all the integer variables use up 2 bytes, which allows numbers up to 32,767 to be stored. Each half of a variable is stored in one byte, and every byte has an address of its own. Here is a program which uses PEEK and POKE to gain access to the TV frame counter. PEEK/POKE REACTION TIMER |

5Ø PRINT "HIT RETURN" 16414 and 16415 are the addresses of the two halves of a 16 bit number which counts the frames on the TV – increasing by 1 every 1/50th of a second. Lines 3Ø to 4Ø set the count to zero, and the count is stopped when a null string is input to C$. There is a delay on all operations (mainly between pressing the return key and this signal getting to the CPU) of around 8Ø mS, hence the 4 subtracted from the expression in line 9Ø. This could have a repeat mechanism tacked on the end, for example: 1ØØ PRINT "DO YOU WANT ANOTHER GO?" Another function which allows the user to communicate directly with the ZX-80 is |

| Page 89 | Contents | ||||||||||||

PEEK, POKE and USR(A) are really facilities provided for very experienced users who understand the detailed working of the ZX-80.

And now, last but not least, DIM. This is of the form

Arrays can have any single-letter name and can have any number of elements (providing that there is enough room to store all the elements). |

It is possible, though not a good idea, to have a variable and an array with the same name Each element is referred to by its subscript. For instance Because you can use any integer expression as a subscript it is possible to process array elements easily and quickly. Here is an example of the use of arrays for character manipulation. CHEESE NIBBLER |

||||||||||||

| Page 90 | Contents |

|

1ØØ FOR J=1 TO 1Ø 2ØØ FOR J=1 TO 1Ø 3ØØ FOR J=1 TO 1Ø |

4ØØ FOR J=1 TO 1Ø 445 PRINT "HIT NEWLINE TO NIBBLE THE CHEESE" 5ØØ LET I=RND(1Ø) 1ØØØ STOP When typing in a program like this where there are several similar lines the EDIT facility is very useful, because you can edit line numbers. |

| Page 91 | Contents | ||||||

|

FOR example; after entering line 21Ø, type: EDIT Statements 1Ø to 3Ø set up 3 arrays, A, B and C of 1Ø elements each. Statements 1ØØ to 14Ø set all elements of all arrays to 1. 2ØØ to 24Ø examine each element of the array A in turn. If an element is equal to 1 a Similarly for 3ØØ to 34Ø and 4ØØ to 44Ø. On the first pass all the elements are set to 1 and 445 to 47Ø print the instruction and if the user then hits NEWLINE the screen is cleared. 5ØØ to 54Ø select a random element of a random array to set to Ø. |

At 55Ø the program jumps back to print out all the arrays. The element which has been set to Ø is printed as a space – or nibble. As more nibbles are taken there is a greater chance that the element selected will already be Ø and thus the effective nibble rate slows down as the game progresses.

|

CHAPTER15OVER TO YOU |

| Page 95 | Contents |

OVER TO YOUIf you have read all the way through this book, running the programs in it and writing your own, you should be well on the way to becoming a fluent BASIC programmer. Remember, though, that there are many things you can do with ZX-80 BASIC which you can't do using other BASIC's. Equally, some BASIC's have features which are not present in ZX-80 BASIC. The appendices present a concise summary of the error codes and the ZX-80 BASIC. Section 2 of Appendix 2 is written with experienced users in mind, but most of it does not require a detailed knowledge of the working of the central processor. From now on it's up to you! |

|

APPENDIXIERROR CODES |

| Page 99 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ERROR CODESWhen results are displayed, a code

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

APPENDIXII4K BASIC FOR ZX-80 |

| Page 103 | Contents |

4K BASIC FOR ZX-801. ZX-80 user's view. The computer maintains a "current line number" for editing the program and the display is always organised so that the line with that number, or the preceding line if no line with that number exists, is on the screen if at all possible. *RAM stands for random access memory, or store. |

If there is a line with the current number, it is displayed with a symbol consisting of a reverse video Three keys are provided for changing the current line number: " There are two other ways [in] which the current line number can change: inserting a line into the program sets it to the line number of that line, and the command "LIST n" will set it to n. When the current line is off the top of the screen, the window moves up so that it becomes the first line. When it is at or just off the bottom the window moves down a line. If it is well beyond the bottom of the window, the window moves down so that it becomes the second line on the screen. |

| Page 104 | Contents | ||||||||||

|

(b) Input area Somewhere in the line a "cursor" is displayed. This indicates two things: the position in the line where symbols will be inserted, and whether an unshifted alphabetic key will be treated as a keyword (eg "LIST") or a letter (eg "A"). The cursor is in the form of an inverse video Note that this cursor, although displayed in the line and occupying a character position on the screen, does not form part of the line and is ignored by anything interpreting the line. A second symbol, similar in principle to the cursor, may also be displayed: this is in the form of an inverse video |

is input from left to right then

In most cases the symbol is displayed as far to the right as is consistent with the above description; however there are a few circumstances where this is not quite so, for instance in The following keys are available to alter the input line:

|

| Page 105 | Contents | ||||||||||

Each of these is stored in the computer as a single byte, which, as in (i), is inserted to the left of the cursor. However, they appear on the screen as more than one character. Those that are alphanumeric (ie all except "**") are preceded and followed by a space, the preceding space being omitted (a) at the beginning of the line (b) where it follows another alphanumeric token. (This rule means that programs appear well-laid-out on the screen without using up scarce RAM space for explicit space characters. Inserting an explicit space character before or after an alphanumeric token always inserts one extra space in the displayed form.)

|

(c) After input A special case is where the new line consists only of a line number, possibly preceded by spaces: the existing line (if any) is deleted but nothing replaces it and it therefore simply disappears from the listing. The "current line number" is still set to its number, however, so the inverse video |

| Page 106 | Contents |

|

A line which has no line number, or which has line number zero, is a "command" and is obeyed immediately. For as long as it takes to obey the command (which for most commands is very brief) the screen is blank, then on completion the upper part of the display contains any output generated and the lower part contains a display of the form If m = Ø, execution was successful; if m = 9 a STOP command was executed; otherwise m is an error code (see Appendix I). Where a command (RUN, GO TO, GOSUB, CONTINUE) has caused the program to be entered, n is the line number of the offending instruction if m is an error code (exception: if the error is in a GO TO or GOSUB then n may be the target of the jump), the line number of the STOP if m = 9, and the line number of the last line in the program if m = Ø. Except in the case of m = Ø or m = 9, CONTINUE is a jump to line number n (but see 3(c)). If m = 9, CONTINUE is a jump to line number n + 1. |

Sometimes only the first digit of n is displayed because there is no room in the RAM for any more display file. For example beware confusing line number 24Ø, of which only the first digit is displayed, with line number 2. A jump to a line number which is beyond the end of the program, or greater than 9999, or negative, gives m=Ø, n= the line number jumped to. The commands are described individually in section 3. 2. Computer's view (a) RAM |

| |

| Page 107 | Contents |

|

The first area is fixed in size and contains various "system variables" which store various items of information such as the current line number, the line number to which CONTINUE jumps, the seed for the random number generator, etc etc. Those that could possibly be useful with PEEK etc have been documented elsewhere (Appendix 3). An important subset of the system variables are the five contiguous words labelled VARS to DF_END which hold pointers into the RAM and define the extent of the remaining areas (apart from the stack). The program consists of zero or more lines, each of the form |

The program lines are stored in ascending order of line number. The text consists of ordinary characters (codes Ø to 3Fh) and tokens (codes CØh to FFh), although reverse video characters (codes 8Øh to BFh) have also been allowed for. The variables take the forms shown on the next page. They are not stored in any particular order; in practice each new variable is added onto the end. When a string variable is assigned to, the old copy is deleted and a new one created at the end. The "variables" area is terminated by a single byte holding 80h (which can't be the name of a string!). |

| Page 108 | Contents |

| |

|

The working space holds the line being input (or edited, hence "E_LINE" except when statements are being obeyed when it is used for temporary strings (e.g. the results of CHR$ and STR$) and any other similar requirements. The subroutine X_TEMP is called after each statement to clear it out, so there is no need to explicitly release space used for these purposes. The display file always contains 25 newline characters (hex 76); the first and last bytes are always 76h and in between are 24 lines each of from 0 to 32 (inclusive) characters. (DF_EA) points to the start of the lower part of the screen. |

The stack (pointed to by register SP) has at the bottom (high-address end) a stack of 2-byte records. GOSUB adds a record to this stack consisting of 1+ its own line number; RETURN removes a record and jumps to the line number stored therein. The last 2 bytes of RAM contain a value which RETURN recognises as not being a line number. |

| Page 109 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The expression evaluator (which is also used to check the syntax of expressions) pushes 4 bytes onto the top of the stack for each intermediate result and pops them again when the appropriate operator is found, eg.

Thus the above expression uses a maximum of 12 bytes of stack. Parentheses use an additional 6 bytes each, eg. Apart from these two cases, the stack is only used for subroutine calls and for saving registers. (b) Actions |

Each time a symbol or token is inserted into or deleted from the input line, also each time the cursor is moved, this change is put into effect in the input line held in working-space after deleting the lower part of the display file (viz that part from (DF_EA to DF_END) – note that during this period the display file may be incomplete in that less than 25 newline characters are present, although the display file is never allowed to become large enough that there will not be room to hold the remaining newline characters). Then the input line is checked to see if it is syntactically correct. The input line contains an inverse video If there is now insufficient room for the display file the display file area is cleared and the upper part is remade with fewer lines by re-copying from the program stored in the area from RAMBOT to (VARS), again converting tokens into characters as part of this process, and the lower part is then output afresh. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 110 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||

|

When a line is to be inserted into the program, its line number is converted into binary, space is made at the appropriate place by copying everything else up, and the text of the line (from which the cursor has already been deleted) is copied in. The working-space and display file are then re-made, the former now containing just the cursor and a newline. When a command is executed, it is interpreted in situ in the working-space area. Program lines are of course interpreted in their place in the program. 3. Statements String expressions are:

|

|

| Page 111 | Contents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Integer expressions are:

|

Ambiguities in parsing operations are resolved by considering the priority of the operators in question: higher priorities bind tighter, equal priorities associate from the left. Example:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 112 | Contents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Values of string expressions can be of any length and can contain any codes except 1 (the closing quote). Values of integer expressions must be in the range -32768 to 32767; any value outside this range causes a run-time error (number 6).

|

also

so that for instance I AND I>Ø OR -I AND I<Ø is the same as ABS(I). However constructions such as A>B>C do not have the obvious effect, being parsed as (b) Statements

|

| Page 113 | Contents | ||||||||||||||

The above can all be used in programs, but are intended to be used as commands, and use in programs is not particularly sensible.

|

|

| Page 114 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

The INPUT statement cannot be used as a command because of the conflict in use of the working-space; however, in this situation LET can be used instead. Using INPUT as a command causes error code 8/-2. If "dest" is an array element and there is an error in evaluating the subscript or the subscript is out of bounds the error is not reported until after the input value has been submitted.

|

|

| Page 115 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| Page 116 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note that this does not preclude (i) assignment to a (ii) several NEXTs matching one FOR, or one NEXT matching several FORs. Note also that FOR – GOSUB – NEXT – RETURN, and FOR I – FOR J – NEXT I – NEXT J are possible, though not very useful. (c) BREAK |

4 Character set

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page 117 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Characters marked ¹ not available from the keyboard. Codes 38–63 only available when cursor is |

APPENDIXIIISYSTEM VARIABLES |

| Page 121 | Contents | ||||||||||||||

SYSTEM VARIABLESThe contents of the first 40 bytes of RAM are as follows. Some of the variables are 1 byte, and can be POKEd and PEEKed directly. The others are each 2 bytes, and have the low order byte at the given address (n, say) and the high order byte at the next address. Thus to poke value v at address n do The notes at the lefthand side of the table have the following meanings:

|

|

| Page 122 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| Page 123 | Contents | |||||||||||||||

|

The first line of program begins at address 16424. The function RND generates a pseudo-random number from the current "seed" as follows:

|

| Page 124 | Contents |

|

The TAB function in printing can be implemented as follows: |

|

INDEX |

| Page 127 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| Page 128 | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Science of Cambridge |