|

A lookalike, soundalike Torch, but Susan Curran finds plenty to distinguish it from the old flame. How bright the Tiger? |

|

Contrary to the received wisdom of a year or two ago, the 8-bit business micro is not dead yet. The Epson OX-10 has hit the best-seller lists, and on a more modest scale Cambridge is making a name for itself as the home of 8-bit multiprocessor colour communicating micros. A pretty limited class, one might think, and it's hardly any wonder that Torch should have grumped when its neighbour H/H came up with the lookalike, soundalike Tiger. In fact there are plenty of differences between the two machines — different secondary processors, for a start — but there are real similarities, too. |

Though this is H/H's first computer, it isn't the proverbial two-men-and-a-dog new computer company, but a fairly large and established manufacturer of electronic audio equipment. The Tiger's design was bought in from Tangerine, but the machine has been assembled by H/H. The first prototypes saw the light of day in the summer, but H/H didn't offer the machine for review until it was in production, and the model I looked at is a production version. It's a three microprocessor computer. A Z80A running at a nifty 4MHz does the main processing and gives access to the inevitable CP/M based business software. That has 64K of RAM, of course, plus a small (0.5K) CMOS RAM used to hold phone numbers and similar rarely-changing information. |

There's a 6809 — better known as the graphics-oriented chip inside the Dragon 32 — as an Input/Output controller, with 2K of RAM to itself. And there's a mighty 96K of RAM dedicated to the graphics, with an NEC 7220, a very highly regarded new chip, to control it. This makes for a comparatively speedy CP/M machine with exceptional colour graphics capability built-in. There's also a built-in auto-dial, auto-answer modem, which gives access to Prestel, and makes for easy computer-to-computer communications. 'It comes with most of the extras built in' |

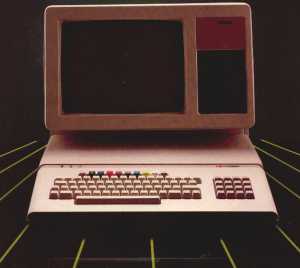

PresentationThe Tiger arrived exactly when promised, in two large cardboard cartons, and with a mountain of software. It's a departure from the normal three-box design. Instead, there's a keyboard and processor unit, looking rather like an oversized Dragon or BBC micro, and a separate combined monitor and disk unit. This is a strange and, to me, rather puzzling choice. It gives the machine a massive footprint, for a start. Even when the CPU/keyboard is pushed as far under the monitor as it will go (it still sticks out a fair bit), the configuration takes up 79cm from front to back. It's going to need a desk to itself. |

The CPU is elegant and low, with a nicely raked keyboard, but it's too slim to hold any expansion boards. But to be fair, the Tiger comes with most of the extras you might want built in. The drive/monitor unit takes up, if anything, less space than it would if it held a main board and an expansion cage, and the two need to be linked by three separate cables: one for the VDU, one for the disks, and one for the power supply. All of the ports are located at the back of the CPU unit, except for the disk connectors (three, allowing for expansion) which snake from its underside — again, rather BBC-like. There's a cassette port, which is very unusual on a business machine, and once more like the Torch — though on that its handy for BBC software. |

There's also the option of a UHF controller, so you could, if you wished, carry the CPU unit home and use it as a home computer. [But what about the disk drives?] However, the Tiger isn't portable in the conventional sense: the CPU unit alone weighs a hefty 13lb. Both cases are finished in a creamy beige, and the general design is solid and pleasing. The box even included a 'Tiger Care' impregnated cloth for wiping the computer clean. The machine has minimal options for expansion — or contraction — at the moment. The dual floppy colour version is standard, though it's possible to add either further 5¼in or IBM-compatible 8in floppies, or a hard disk to it. It comes complete with CP/M, but without any applications software included in the price. |

DocumentationTiger's approach centres around presenting a nicely finished product, with all the loose ends tied up before it hits the market. The Programmers' Manual wasn't complete at the time of review, but the User Guide and Reference Manual both came in a finished form. There's also a very slim document which describes the demonstration graphics programs included on the system disk. |

The User Guide is a clearly written effort aimed at putting across the basics to a naive audience. It includes pictures and diagrams, and gives the basic information needed to get the system working. The Reference Manual is aimed at high-level programmers and other more sophisticated users, and contains enough information on CP/M and on the graphics commands to get a Basic programmer started. Again it's well written, and working from it I had no trouble using the graphics capabilities from Basic. However, it's short on technical information, which is where the Programmers' Guide will presumably come into the picture. |

H/H isn't a secretive company: the sales brochure contains a larger colour picture of the neat main board, with all components labelled and described. I went back to them with a few queries, and received clear and lengthy instructions over the phone. Both these guides are excellent examples of their kind, as are Tiger's software manuals. They are all spiral bound, with appealing and reasonably robust blue covers. |

KeyboardThe main keypad is a creamy beige to match the computer casing, while the cursor control/numeric keypad is slightly darker. The ten functions stand out a mile: eight of them are brightly coloured in the eight screen colours. Outside programs they are used for changing foreground and background colours, and it's easy to tell which controls which colour. |

There's a sensible, and not unduly expansive, key layout, with caps lock (which locks down mechanically, as on a typewriter — a nice touch) and shift lock (with an associated light), keys in the conventional places, and a couple of extra screen controls. It was disappointing to discover, however, that the entire keyboard is hard, so not even the function keys can be reprogrammed. That is, they can be read by application programs, but they can't be programmed to return a string of commands. |

The character set isn't large by current standards, and both hash and pounds keys returned the same code which doesn't generate a pounds sign on my printer. Otherwise, it's a pleasant keyboard with positive feel. The reset button is sensibly and safely located on the underside of the CPU unit. There's a type-ahead buffer, which worked, albeit sometimes unpredictably, in the word processing package. |

The most obvious visual feature of the Tiger is its large 'footprint' (the surface area occupied on the desk-top). Some of this bulk is apparent in the rear view (above). The colourful function keys are eye-catching (below) but not as interesting as the design might indicate. They cannot be programmed to return a string of commands; they can only be 'read' by the application program. |

The rear of the CPU snuggles in against the combined VDU/disk drive unit — most of the necessary connectors are located here. |

The three disk drive connectors are under the front of the keyboard. | |

| |

DisplayDisplay is the Tiger's strong point. There's a large and clear 14in colour screen, with the standard eight teletext colours, all coming across brightly. This version was reputedly coated with long-persistence phosphor (available as an option for graphics applications) but it behaved quite normally for text and was slightly flickery for graphics, so perhaps this wasn't really the case. I had no trouble working with my back to a window, so I didn't try to adjust the contrast, which is a tricky business involving a screwdriver. No other controls are provided, and the screen can't be tilted, though I didn't find this a problem. |

Three modes are available: 80 x 24 text, teletext-type 40 x 24 text, and graphics. The full colour range is available in both modes, and the teletext attributes can be set in either serial or parallel, so there's no need to leave gaps on the screen when changing them, as there is with the BBC/Torch. The character set is clear and pleasant, and there are mosaic graphics, but no little men, copyright signs or other extras. It isn't possible, as far as I could tell, to redefine or add to the character set. 'The display is the Tiger's strong point' |

One interesting possibility is to set up two displays, one to show graphics and the other to hold a text screen while developing a graphics program. This is quite feasible if a second VDU port is fitted as an option. In graphics mode a square 512 x 512 pixel area of the screen is used, leaving a large black border. All graphics commands are given by reference to pixel addresses, and the screen is numbered fairly conventionally from the bottom left-hand corner. The graphics commands provided via the 7220 include line and point drawing, circle and rectangle fill and outline, and a rather awkward way of incorporating text. |

|

There's a pattern register which can be used to fill areas with patterns or to simplify producing intermediate shades, and shapes can be rotated. The most powerful features are the pan and zoom commands. It's possible to enlarge any area of the display up to 16 times, and then to pan across giving pixel address to locate the display area. This feature is shown to good effect in the otherwise rather pedestrian demos that come on the CP/M disk. A special graphics demo disk provided some exciting examples. |

Naturally, all eight colours can be used at any position on the screen, so there's no difficulty in producing very detailed multi-coloured graphics. All the graphics commands are given by ASCII sequences when in graphics mode, and I managed to access them from the unexpanded Microsoft Basic, using rather clumsy strings of PRINT commands. A serious user would obviously need purpose-written software, but this pretty basic method produced displays which were written and updated at a very acceptable speed. |

StorageThe drives are Mitsubishi-made, and very high capacity: 1 megabyte unformatted, and around 720K formatted. I found them a little noisy during access, but very reliable. The fan incorporated in the display/drive unit was, in contrast, commendably quiet. |

|

|

The VDU unit (left) needs a fan to keep the tube and twin disk drives cool. Unfortunately, the silence generated by the fan can be drowned by the rather noisy drives. The three processors and associated RAM are housed in the keyboard unit (right). | |

SoftwareTiger has a very strong policy on software. All the dozen or so packages arrived in Tigerbyte-labelled boxes with Tiger-oriented names on them: Tigerword, Tigercount, Tigerlist and so on. Inside many of them were unadulterated Peachtree manuals with quite different names, but when it came to the floppies Tiger had gone back to work, and every one was neatly wrapped in a sealed polythene bag, and encased in the regulation pale blue and white. By far the biggest stack was of Peachtree software, including Peachtext, a Spelling Proofreader, Mailing List Manager, Inventory Management, and a complete set of accounting ledgers. Peachtree produces beautiful manuals in cloth-covered ring binders, encased in green library cases. |

Inside, they are all clearly written and properly anglicised. There was even found an apology when a command demanded an American spelling. The packages have been properly adopted [sic] to use the Tiger keyboard, with clear plastic function key overlays provided for a couple. The accounting software wasn't tested though it looked very competent: the payroll included statutory sick pay and so on. Peachtext/Tigerword, which I hadn't encountered before, proved to be a pleasant surprise. It has a clear editing screen, good commands, and a lot of power, though it's not quite up to Wordstar standard in handling long documents. The main problem with this — and to a lesser extent with Wordstar — was on the screen handling. |

Both packages obviously had difficulty making proper use of the screen memory, and rewrote the screen continually instead of scrolling. Moving backwards in the text was a particular problem. Peachtext swaps regularly between a text screen and an editing status screen, and with 96K to play with it seemed a little ridiculous that it couldn't hold both in memory instead of rewriting on each swap. The rewrites were fairly fast, but not fast enough; the program otherwise responded very promptly. |

|

Tigerplan appears to be an implementation of Sapphire's MARS spreadsheet/management reporting/business graphics system, and this worked well. There was also the inevitable Microsoft Basic, version 5.2.2, and Tiger's own Prestel program which has a few touches that Torch's lacks. No obvious gaps, but the communications software, Prestel apart, is admittedly not yet anywhere near Torch's standard. All the software packages seemed to be sensible choices, and when I mentioned packages not originally included — Wordstar, BBC Basic — to Tiger, copies of these too turned up in short order. |

However, it may be that most would-be buyers will want to know which well-known package Tigerword, say, is before forking out several hundred pounds. Tiger is really an applications micro, and languages lag behind business packages, but the Microsoft standards — Cobol, Fortran, Pascal — should all appear shortly, and probably Forth too. As it's a standard CP/M machine and can take programs straight off standard format 8in disks, there should be no problem in obtaining any CP/M software. Graphics software is obviously crucial, Digital's GSX package was almost-but-not-quite ready at the time of review, but the well-established mini-based GINO-F was up and running. |

A demo came in time for review, with the real thing promised a few days later. As I'm no Fortran programmer (GINO's a set of fortran subroutines), the demo did fine. GINO covers a wide range of business graphics and CAD territory, and can handle shape mirroring, rotation, scaling, shearing (that is, perspective effects) and 3-D. The demos worked fast and impressively, and the package should pack enough power to make the Tiger a good choice for designers. None of the software except CP/M is free, and this is an obvious drawback at a time when bundled software is becoming more and more common. Maybe Tiger will rethink this strategy and offer at least the Basic with the machine before long. |

InterfacesThe usual Centronics and RS232 interfaces are standard, and there's also an IEEE488 — for Winchesters etc — and networking interfaces, a light pen port and the aforementioned cassette port. The latter is clearly an anomaly, and few users will need it. |

There's a jack plug to the phone, as with the Torch. You just plug into a suitable phone socket, and tell the computer to get dialling. This makes the Tiger extremely easy to use as a Prestel terminal, and it should be just as good for electronic mail once software has been developed. In short, a very good range of interfaces, which will fulfil all normal requirements. In useThere's not a great deal more to say about the Tiger in use: when you're not in graphics mode, it's a pretty standard CP/M machine. |

Nothing amazing has been done to make it user-friendly, though it has some nice touches like an inbuilt clock, the CMOS memory — which can be rewritten after adjusting a security switch — and a commendably short start-up routine. After the eccentricities and occasional exasperations of the Torch, it has an air of competent solidity about it. |

|

Though business software has been running on 8-bit micros for years — and this generation of packages is very well proven — 64K of RAM does seem a limitation by today's standards, and one which the high-capacity disks don't altogether compensate for. In conventional use, this RAM limitation is far more significant than the extra processing power which 16-bit machines give. |

The provision of the separate graphics RAM means that a little more than usual is freed for applications use, but there's no easy way to expand the machine in this direction. Tiger has conspicuously not gone for the virtual disk approach used in some other new machines like the Miracle. The machine works fast, but the need for comparatively frequent (compared to 16-bitters) disk access will certainly slow down large-scale applications. |

SupportTiger is clearly going all out for a solid image, carried right through software and support services. The company has appointed around 70 dealers, allocated machines to them, and carried out dealer training before even sending machines for review — a welcome touch in a market where many trumpeted machines aren't even working in prototype. Both machine and software reeked of quality. |

VerdictObviously 8-bit colour graphic communicating micros aren't everyone's cup of tea, and with this mix of capabilities the Tiger is markedly more expensive than a very basic CP/M machine, even though it compares favourably with most such machines expanded to support colour graphics. Tiger would make a superb upmarket executive machine, the Rover of the micro world perhaps, particularly with its Prestel capability. And it has obvious appeal for designers, advertising firms and other people who can make full use of this level of graphics capability. Not a machine that's likely to take over the micro market, then, but an excellent choice if you're looking for a computer with colour graphics, Prestel, and reliability for mainstream business applications. |

|