From its

earliest roots, the primary objective to winning a gunfight, be it in

an F15 Strike Eagle or between

desperadoes, has been to get your weapon aimed at your opponent as quickly

as possible. While it seems

that Hollywood made a big deal out of Matt Dillon firing from the hip,

and really, probably everyone

reading this practiced the same feat as a kid, the concept was just as

applicable then as it is now. But,

before anyone gets to thinking that I’m endorsing point shooting,

I’m not. Although I’ve practiced it, like

most people I have never been worth a damn at it beyond three yards. Granted,

I have witnessed people

who were uncannily accurate at it out to ten or more yards. What Hollywood

never seemed to grasp was

that the classic quick draw stance was something used when an opponent

was at arms reach, not squared

off at twenty paces.

Death in

a western-era saloon (or the streets of modern-day Chicago for that matter)

was not about the

courage to step out into the center of the street for a fair fight. More

often than not it was about one drunk,

pissed off cowboy spontaneously shooting another drunk, pissed off cowboy

just as soon as his gun cleared

leather. Frequently the shot came from so close that the victim was clearly

marked by powder burns.

What I’m

talking about here is known currently as the speed rock. Sure, most of

the famous gunfighters

who lived past thirty were known to draw, go to an offhand stance and

use sighted fire to stop their

adversary. But romanticizing aside, most of the gunfights of the Old West

were between nobodies in heat-

of-the-moment altercations that occurred at contact distance where the

winner was the cowboy or lawman

who could get his 1860 Army upholstered and leveled the fastest. No finesse,

just shoot the thing before

the other guy gets his

out, too.

The speed

rock gained new use in the late fifties and early sixties with the competitive

quick draw fad.

Because of the simple requirements, shooters refined this sport far beyond

practical (or historical) use in

the name of winning. Whatever could be done to draw and bring your weapon

to bear was tried. Low-slung

metal-reinforced tie-down holsters, half pound trigger jobs, short barrels,

and even peculiar body angles

were employed to shave off every last nanosecond. But at its heart, competitive

quick draw was all about

a shooter getting in the first shot, accuracy be damned!

Eventually

the Matt Dillon fad faded and most police agencies that had used any type

of point shooting

began to return to various forms of aimed fire as the Weaver stance gained

following. Oddly enough

though, reexamining the average statistical gunfight or assault showed

more and more that they occurred

at incredibly close range. At the same time, police agencies, through

collective data, were realizing that

two of the biggest killers of peace officers were the high speed pursuit

and officers who were killed with

their own weapons. The buzzphrase for the decade became "Weapons

retention."

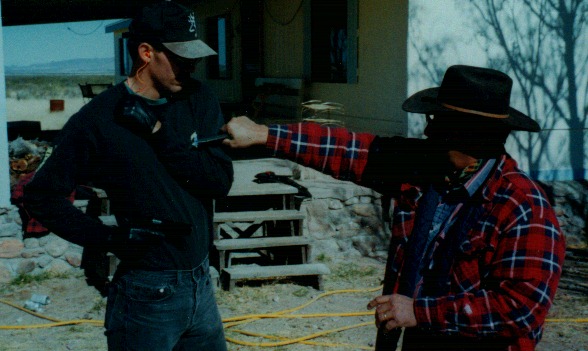

As seen

here, the weak arm is pulled back against the body to get it out of the

fire zone as well as providing

shielding to your upper chest cavity. The strong hand and weapon are rotated

to the firing position as soon as the

muzzle clears leather. Use of a standard interview stance will put the

strong side farthest from the attacker. This

move should be done at a full retreat. At this range you are only exchanging

wounds, put some distance between

you and your attacker while those bullets soak in.

schools. Designed to allow a shooter to draw a weapon from a strongside holster, rotate it to firing position

as soon as it cleared leather, and fire while keeping the weapon relatively safe from a gun grab, the Speed

rock stance was reborn.

While many

professionals had long ago (my father switched in the early sixties) taken

to carrying autos,

most police and security still clung to their revolvers. But as times

changed and Hollywood made high

capacity autos seem almost magical, agencies began to switch over to magazine

fed weapons. Where this

caused an evolutionary change to occur in the speed rock was in the fact

that the trusty revolvers of the

frontier would feed reliably regardless of how they were held so long

as you pulled the trigger.

But now we

had autos that were often sensitive to limp wristing. Every 1911 or clone

has varying degrees

of sensitivity, but compact weapons like the Detonics 45 and later the

Glock subcompacts absolutely

disliked being fired from a true speed rock. Not only that, many shooters

found they had trouble aligning

their weapon on both a horizontal and vertical axis. The stance solved

a few problems, but created a few

more.