Looking through scientific publications concerning orchids, as well as other biological subjects, one frequently comes across magnificent images filled with detail, made using a scanning electron microscope. Orchid seed images are amongst the best, although I find the mouthparts of insects another exciting field. Unfortunately most of us cannot afford to keep a scanning electron microscope with attendant technician in our basements.

Examining seed under a normal light microscope fails to show off much detail at all, although by repositioning the condenser, one can get some sort of phase contrast effect, which may reveal some extra detail.

Some years ago, my late father managed to get a lightly-tinted pair of plastic polarising dark glasses into the mechanism of his lawn mower. This was one of his specialities; quite a number of spectacles went the same way. Later I found what was left of this pair of dark glasses on a shelf in the workshop, and decided to see if I could convert it into polarising filters for my microscope. With the use of some coins of a suitable size, what was left of the lenses was marked out, and the unwanted material ground away on a bench grinder.

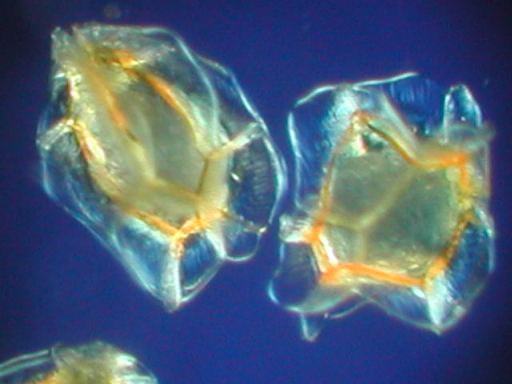

Polarised light microscopy is an old technique, which involves examining a specimen between crossed polarising filters. When light passes through one such filter, only that portion of the light wave vibrating in one specific, defined plane will pass. A second filter polarising light in the same direction as the first, will allow the light to pass unimpeded; however if one rotates this second filter through a right angle, no light will be able to pass. Certain components of microscopic specimens are able to rotate polarised light, so that after the light passes through the specimen, even though the background light is extinguished by the second filter at right angles to the first, that portion of the light that has been rotated, will pass through the second filter. The images produced are not only useful, but often also very beautiful. Many minerals can rotate polarised light, so this form of microscopy is much used in the mining industry. It is less widely used in biological studies.

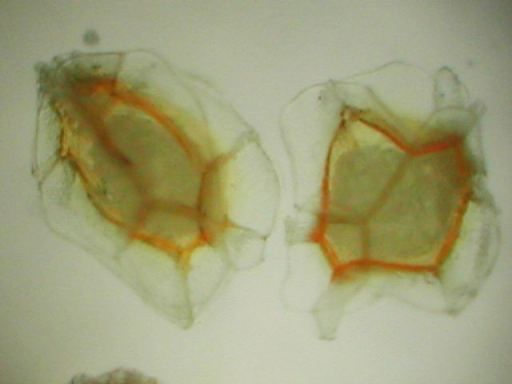

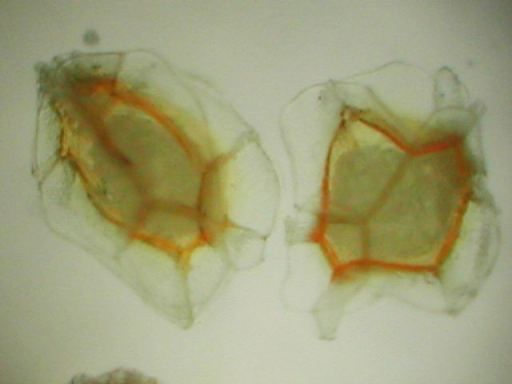

In plants, one of the components which is capable of rotating polarised light is cellulose, the widely-occurring structural polysaccharide of plants. The coats of orchid seeds are made up of cellulose fibres, and I have found that examining seed under a microscope between polarising filters creates useful images with considerably more detail than one can obtain by any other "kitchen" method.

Of course, one does not have to get as "kitchen" as I do, one can usually buy suitable filters specially made for one's microscope, but naturally at quite a cost.