Western Australia c.370 million years ago.

Beneath the clear sunlit waters of an ancient reef, a lobe-finned fish rests on the seafloor. Hundreds of millions of years later, its perfect fossil skeleton will help us to understand how the first four-footed vertebrates (tetrapods) evolved from piscine ancestors and went on to conquer the land.

Gogonasus andrewsae is just one of dozens of fish species described from the exceptional Gogo fossil fauna from the remote Kimberleys of northwestern Australia. In the Late Devonian, the area was a shallow sea dominated by a series of tropical reefs built up over millennia by coralline algae and stromatoporoids. The towering limestone cliffs and spires that dominate the dry landscape today attest to a reef complex as majestic as the modern Great Barrier Reef.

When the fishy inhabitants of that reef met with misfortune, their bodies sank to the sandy seafloor and were rapidly encased in calcium carbonate before decomposition set in. Limestone nodules litter the ground today and some contain the spectacularly preserved remains of those ancient fish. Gogo fossils are often 100% complete, in perfect articulation, contain original, unaltered bone and sometimes contain sections of soft-tissue.

Gogonasus is a tetrapodomorph, a group which includes a variety of lobe-finned fish close to the ancestry of the tetrapods as well as the tetrapods themselves (you and I are tetrapodomorphs). It was first described from fragmentary skull remains in 1985 and was thought to be a very primitive tetrapodomorph, only distantly related to land-living tetrapods. Then in July 2005, a near-perfect skeleton (now in the Museum Victoria collections) was discovered by Prof. Tim Senden of the Australian National University which revealed that it was something else.

We now know that the group of fish that gave rise to the Tetrapoda were the

elpistostegalians (a decidedly unsexy name which you may substitute with

"panderichthyian" or the informal "fishapod"). These were large freshwater

predators of Devonian Europe and Canada with extremely tetrapod-like skulls

and limb-bones. Take an advanced elpistostegalian like Tiktaalik,

shave off the bony-scales, replace the fin-rays with digits, make a middle

ear out of the already widened spiracle and shortened hyomandibular and

voila! You have a tetrapod (more or less).

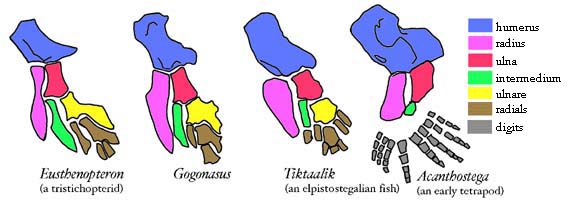

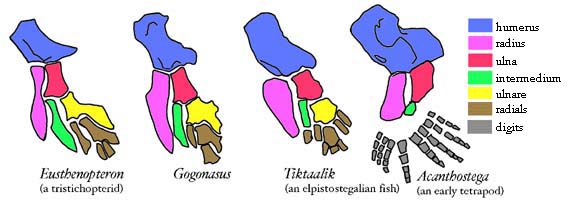

The leap from an elpistostegalian fish such as Tiktaalik to an early tetrapod is pretty small. But until recently getting an elpistostegalian from a less derived tetrapodomorph has been a little bit tougher. Until 2006, the closest known kin of the fishapods were the tristichopterids ("tristis" for short), a widespread clan of freshwater meat-eaters that include the famous Eusthenopteron, often seen as a fish-amphibian missing link in old textbooks. Tristichopterids are in many ways ideal fishapod precursors. For example, their pectoral fins have early versions of the tetrapod upper arm and forearm bones. But other similarities are more remote and require a bit more modification.

Enter Gogonasus! Many aspects of the anatomy of this fish are a mosaic of tristi and fishapod characters with a number of features intermediate between the two. Some of the bones of the pectoral fin more closely resemble those of fishapods than tristis with a flattened rather than cylindrical humerus and a tapering rather than hourglass shaped radius. In other ways, it more closely resembles that of Eusthenopteron, such as in the shape of the ulna. Gogonasus has an enlarged fishapod spiracle unlike the tiny slit of Eusthenopteron. The spiracular chamber is a perfect intermediate between the deep structure of tristichopterids and the narrow, horizontally aligned condition in elpistostegalians. Gogonasus still retains anal and dorsal fins, features lost in the elpistostegalians, while the teeth have the simple internal structure of tristi-choppers with none of the complex labyrinthodont infolding of fishapods and early tetrapods.

above - how fish became armed and dangerous. Comparisons between the left pectoral fins/forelimbs of several derived tetrapodomorph fish and the early tetrapod Acanthostega.

However some features of Gogonasus are more archaic than either tristis or fishapods. It still has a primitive assymetrical tail while its scales contain cosmine, a tissue present in primitive lobe-fins but lost in most derived tetrapodomorphs. That, plus the fact that fishapods were already lurking in the rivers of Euramerica when Gogonasus was cruising the reefs of Gondwana means that it cannot be directly ancestral to the elpistostegalians. However this ancient Australian was clearly closer to that ancestor than any previously known fish and its discovery suggests that, despite the current restriction of fishapods to the intensely studied northern assemblages of the Late Devonian, the origins of the group (and perhaps of the tetrapods themselves) may be awaiting discovery in the more poorly sampled Middle Devonian sites in the south.

above - the reassembled skull of Gogonasus andrewsae.

SOURCE

John A. Long, Gavin C. Young, Tim Holland, Tim J. Senden and Erich M. G. Fitzgerald.(2006) An exceptional Devonian fish from Australia sheds light on tetrapod origins. Nature 443. Nature advance online publishing nature05243.

Beneath the clear sunlit waters of an ancient reef, a lobe-finned fish rests on the seafloor. Hundreds of millions of years later, its perfect fossil skeleton will help us to understand how the first four-footed vertebrates (tetrapods) evolved from piscine ancestors and went on to conquer the land.

Gogonasus andrewsae is just one of dozens of fish species described from the exceptional Gogo fossil fauna from the remote Kimberleys of northwestern Australia. In the Late Devonian, the area was a shallow sea dominated by a series of tropical reefs built up over millennia by coralline algae and stromatoporoids. The towering limestone cliffs and spires that dominate the dry landscape today attest to a reef complex as majestic as the modern Great Barrier Reef.

When the fishy inhabitants of that reef met with misfortune, their bodies sank to the sandy seafloor and were rapidly encased in calcium carbonate before decomposition set in. Limestone nodules litter the ground today and some contain the spectacularly preserved remains of those ancient fish. Gogo fossils are often 100% complete, in perfect articulation, contain original, unaltered bone and sometimes contain sections of soft-tissue.

Gogonasus is a tetrapodomorph, a group which includes a variety of lobe-finned fish close to the ancestry of the tetrapods as well as the tetrapods themselves (you and I are tetrapodomorphs). It was first described from fragmentary skull remains in 1985 and was thought to be a very primitive tetrapodomorph, only distantly related to land-living tetrapods. Then in July 2005, a near-perfect skeleton (now in the Museum Victoria collections) was discovered by Prof. Tim Senden of the Australian National University which revealed that it was something else.

above - nodule containing the skeleton of Gogonasus

as discovered in the Kimberleys in July 2005. The snout of the fish can be

seen protruding from the rock.

The leap from an elpistostegalian fish such as Tiktaalik to an early tetrapod is pretty small. But until recently getting an elpistostegalian from a less derived tetrapodomorph has been a little bit tougher. Until 2006, the closest known kin of the fishapods were the tristichopterids ("tristis" for short), a widespread clan of freshwater meat-eaters that include the famous Eusthenopteron, often seen as a fish-amphibian missing link in old textbooks. Tristichopterids are in many ways ideal fishapod precursors. For example, their pectoral fins have early versions of the tetrapod upper arm and forearm bones. But other similarities are more remote and require a bit more modification.

Enter Gogonasus! Many aspects of the anatomy of this fish are a mosaic of tristi and fishapod characters with a number of features intermediate between the two. Some of the bones of the pectoral fin more closely resemble those of fishapods than tristis with a flattened rather than cylindrical humerus and a tapering rather than hourglass shaped radius. In other ways, it more closely resembles that of Eusthenopteron, such as in the shape of the ulna. Gogonasus has an enlarged fishapod spiracle unlike the tiny slit of Eusthenopteron. The spiracular chamber is a perfect intermediate between the deep structure of tristichopterids and the narrow, horizontally aligned condition in elpistostegalians. Gogonasus still retains anal and dorsal fins, features lost in the elpistostegalians, while the teeth have the simple internal structure of tristi-choppers with none of the complex labyrinthodont infolding of fishapods and early tetrapods.

above - how fish became armed and dangerous. Comparisons between the left pectoral fins/forelimbs of several derived tetrapodomorph fish and the early tetrapod Acanthostega.

However some features of Gogonasus are more archaic than either tristis or fishapods. It still has a primitive assymetrical tail while its scales contain cosmine, a tissue present in primitive lobe-fins but lost in most derived tetrapodomorphs. That, plus the fact that fishapods were already lurking in the rivers of Euramerica when Gogonasus was cruising the reefs of Gondwana means that it cannot be directly ancestral to the elpistostegalians. However this ancient Australian was clearly closer to that ancestor than any previously known fish and its discovery suggests that, despite the current restriction of fishapods to the intensely studied northern assemblages of the Late Devonian, the origins of the group (and perhaps of the tetrapods themselves) may be awaiting discovery in the more poorly sampled Middle Devonian sites in the south.

above - the reassembled skull of Gogonasus andrewsae.

SOURCE

John A. Long, Gavin C. Young, Tim Holland, Tim J. Senden and Erich M. G. Fitzgerald.(2006) An exceptional Devonian fish from Australia sheds light on tetrapod origins. Nature 443. Nature advance online publishing nature05243.