|

|

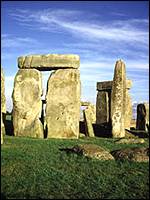

| Stonehenge |

| 1/2 |

| 1/2 |

|

| The most glaring intrusion of Stonehenge are the two roads that appear to dissect the landscape, one of which is so close that it appears to touch one of the stones and is separated only by a chain-link fence. The other passes a little farther away, at about 200 yards from the site. But human invasion has also taken a toll on the ancient monument. In the past, the site has endured the weight of people who have climbed the stones and painted it with graffiti, which has now been erased by the elements. In 1989, the site was roped in because the pressure of so many feet walking among the stones was pounding the grass into dust. Today, only Druids have full access of the site, and only at certain times like midsummer's day "Most people have no ill intent, but just in case, we have to protect it," says Henderson. But interested archaeologists and historians want more than protection of the site -- they want the experience of Stonehenge to be enhanced. And it's just beginning to happen. A newly proposed "Stonehenge Master Plan" involving several groups, including English Heritage, would ensure that the landscape would be returned to its original grandeur by changing roadways, restoring landscapes and improving visitor enjoyment of the site. "What this plan is designed to do is to remove the roads from the landscape so that the larger of the two roads [A303] will be put in a tunnel," says Henderson. The A344, on the other hand, will be covered over with grass and returned back to the landscape. |

|

|

|

|

|

| The most glaring intrusion of Stonehenge are the two roads that appear to dissect the landscape, one of which is so close that it appears to touch one of the stones and is separated only by a chain-link fence. The other passes a little farther away, at about 200 yards from the site. |

| The stone monument fell out of use around 1400 BCE. Its appeal was renewed around the 17th and 18th century when British antiquarians, like John Aubrey, who discovered the 56 "Aubrey Holes," and William Stukeley began to take an interest in the stone monument. Since then, it has been a spiritual site for modern day Druids and top tourist attraction for England, bringing in about 700,000 people a year. "There are all sorts of layers of mystery and interest [in Stonehenge] -- and I think it will always fascinate people," says Elspeth Henderson, public affairs manager at English Heritage, the national governmental body that manages the site on a day-to-day basis. |

| Of the hundreds of stone circles in England, Stonehenge remains the most unique for a number of reasons. It was erected in phases over thousands of years, evolving from a ditch and bank to a complete stone monument of stone circles and horseshoe shaped trilithons -- two stones with one stone laid across the top. Human muscle and a primitive system of ropes and wooden levers moved massive stones far distances to that particular spot on Salisbury Plain, 16 kilometres south of the town of Salisbury in the southwest of England. Once there, special care was used to join the pillar stones to the lintels -- the stones that laid across the top -- with the use of mortice-and-tenon joints, where one stone is shaped to lock into the carved out slot of another. |

| There has also been some discussion over the visitor experience offered at the site. The thousands who visit Stonehenge every year are led to a nearby car park, walk through an underground tunnel and find themselves suddenly beside the stones, which are again roped off. There is almost no recognition of other ceremonial aspects to the site. If the groups initiating the project have their way, a larger and more up-to-date visitor centre will be opened up farther away from the monument with full educational and catering services."The intention is to open up access to the site so that people have the option of going to a visitor centre and getting the full kind of Stonehenge interpretive experience," Henderson says. "But if they don't want to do that, they'll be able to simply walk into the landscape of the world heritage site from a number of directions and have a free run of the whole ancient landscape that it sits in." |

| "When people started paying attention to Stonehenge, back in the 18th century, people like William Stukeley were calling it a temple," says Witcombe. "That sort of association has been more or less attached to Stonehenge for the last two or three hundred years." Others, like 20th century British astronomer, Sir Norman Lockyer,also saw Stonehenge as a temple, but a temple to the Sun. For him, its significance lay in elebrations of ancient Celtic festivals. But to see Stonehenge as a temple, or retaining a religious quality may just be an assumption. It is a structure that clearly does not resemble a house or hall or anything else secular, which could indicate that it is sacred, according to Witcombe. We're also influenced by the fact that a lot of the more complex buildings that survive from the ancient past, like in Greece and Egypt, are buildings that are religious," says Witcombe. "We are presuming that's also the case with Stonehenge." There are also more than 400 burial mounds surrounding the ancient monument. |

| Many of these graves have been found to contain gold breast plates and other precious metal items. These people may have wanted to be buried close to Stonehenge, which could reinforce a spiritual aspect, or as modern day astronomer Gerald Hawkins says in his book, Beyond Stonehenge, a concern for life after death. In the middle of the 20th century, a new theory was born -- one that suggests that Stonehenge could have been used as an astronomical calendar, marking lunar and solar alignments. If this is true, it would have held great power for the people who controlled the megalithic monument. "Astronomers, just because of what they were able to do, must have seemed, to the ignorant, something esoteric and mystical," says Witcombe. Aside from the sarsen horseshoe trilithons that open in the direction of the sunrise, there are four stones, called "Station Stones" that may have played an astronomical role. These were placed in a rectangle around the main monument, within the ditch and bank that surrounds the circle of stones. These are believed to point out the moonrise, moonset, sunrise and sunset. Only two stand today. One of the first people to propose the idea that Stonehenge could have been a tool used in understanding the heavens was 20th century astronomer Gerald Hawkins. He proposed that Stonehenge, which he called a primitive astronomical computer, could predict events of the Moon and Sun as well as eclipses. Hawkins discovered astronomical patterns in the station stones, possibly erected in the first phase of building, and within gaps between trilithons set up the last phase of building. This connection was made by computer calculation, based on maps and charts. It led him to believe that because astronomical properties could be found in two aspects of the monument, there is definite evidence of a heavenly purpose. Modern day astronomer, Fred Hoyle, tested Hawkins hypothesis. "I set myself the clearcut target of finding out if the stones that exist at Stonehenge could, in fact, be used to predict eclipses -- and it seemed to me that they could." 56 Aubrey holes shown here were believed to be a tool of the heavens. Hoyle took a slightly different approach to Hawkins. His calculations are based on the 56 pits or "Aubrey Holes" first discovered in the 17th century by British antiquary John Aubrey. These holes can be found on the inside circle created by the ditch and bank, or henge. Hoyle believed it was possible to determine eclipses by moving three markers, or stones, around the Aubrey holes in such a way that when all three arrived at the same hole, an eclipse of the Sun or Moon was about to occur. But Stonehenge may not have always been used in this way, according to Hoyle. He believes that the first phase of building, where it was simply a ditch and bank with 56 pits (the Aubrey holes) carved out on the inner side of the henge, is the only section of Stonehenge that holds astronomical value. "I was convinced that the inner part, which was built around 1500 BCE, was really mostly a matter of simply religious construction," Hoyle says. "I thought the people who built the first structures there, approaching 3000 BCE, were the cleverest and that the later people didn't know what they were doing." |

| The visitor centre will be implemented first and is expected to open in 2003 at the earliest. Next in the plan are road improvements, anticipated to begin in 2005 and finish by 2008. The last phase includes restoring the general landscape surrounding Stonehenge. The entire project, once finished, will take at least 10 years and cost ?25 million pounds. Other groups involved in the plan include The National Trust, DCMS, DETR, English Nature, the Highways Agency, and Salisbury District and Wiltshire County Councils Stonehenge itself remains a steadfast observer of the world, watching the seasons change from summer to fall to winter to spring and back again thousands of times over. But it also bears witness to movements in the heavens, observing the rhythm of the Moon and, more noticeably, the Sun. For most parts of the year, the sunrise can't even be seen from the centre of the monument. But on the longest day of the year, the June 21st summer solstice, the rising sun appears behind one of the main stones, creating the illusion that it is balancing on the stone. This stone, called the "Heel Stone", sits along a wide laneway, known as the Avenue, that extends from the northeast corner of the main monument. The rising Sun creeps up the length of the rock, creating a shadow that extends deep into the heart of five pairs of sarsen stone trilithons -- two pillar stones with one laid across the top -- in the shape of a horseshoe that opens up towards the rising sun. Just as the Sun clears the horizon, it appears to hover momentarily on the tip of the Heel Stone. A few days later, on midsummer's day, the sun will appear once again, but this time, it will begin to move to the right of the heel stone. The same phenomenon happens again during the winter solstice, only it's in the opposite direction and a sunset. But both indicate a change of season. But who would have needed to make this connection between Earth and Sun. The first builders, who may have just started farming the land, might have needed to know when the seasons were about to change. At a later phase in its development, Stonehenge may have been used as some sort of temple, or it could have been an astronomer's tool, used to judge the movements in the heavens. "Nobody really knows at all what [Stonehenge] was intended for," says Christopher Witcombe, a professor of art history at Sweet Brian College in Virginia and an authority on Stonehenge. "The fact that it was built over a long period of time makes it difficult to know if it maintained the same function over the time period or not." But this doesn't mean there aren't a number of theories that set out to explain Stonehenge's purpose. Eighteenth century British antiquarian, William Stukeley, was one of the first people to report seeing the event of the sunrise on that special day in June. This led him to believe that Stonehenge was a temple, possibly an ancient cult centre for the Druids. Although this theory isn't as popular now, the religious aspect attributed to Stonehenge has influenced how it has come to be understood, even today. |

| And there may be many more theories that haven't even been explored or discovered yet. One just proposed suggests that Stonehenge is a sexually symbolic site, with both male and female represented in stone. "In some cases, some of these ideas may initially sound a bit wacky, but you never know -- there may be one or two aspects of them which may indeed have some bearing," says Witcombe. Although the purpose of the stone monument is still unsure, most people think its worth preserving, for one reason or another. |