Vincent Shen

Working Paper, Dutch-Flemish Association for Intercultural Philosophy NVVIF

| Intercultural philosophy, Confucianism,

Taoism Vincent Shen Working Paper, Dutch-Flemish Association for Intercultural Philosophy NVVIF |

|

| Nederlands-Vlaamse Vereniging voor Interculturele Filosofie |

Address given at 1998 Annual Meeting of

Dutch/Flemish Association of Intercultural Philosophy, 27

November 1998, Philosophical Faculty, Erasmus University

Rotterdam

Prof. Vincent Shen

European Chair of Chinese Studies, IIAS,

Leiden University

Professor of Philosophy, National Chengchi University, Taipei

© 2000 Vincent Shen

One of the reasons why today we need to conduct intercultural philosophy is that philosophy was, and still is, culturally bound. Western philosophy was very much related to the long cultural heritage from ancient Greek, through Rome, to Mediaeval and modern Europe; whereas in other cultures, for example, in Chinese culture, we find also other traditions of philosophy. As Martin Heidegger has well articulated, Western philosophy was in fact a choice made by the Western culture from the times of Parmenides and Plato. Although many histories of Western philosophy were written and entitled “The History of Philosophy”, this exclusiveness and arrogance did set aside arbitrarily many other possibilities.

In this context, to study intercultural philosophy means not to enclose one’s own vision of philosophy within the limit of Western philosophy. This is especially necessary today when the type of rationality which was given foundation by Western philosophy and which was essential to the development of modern Western science and technology, is now much challenged and even collapsing. Now the world is open to other types of rationality, or better say, to more comprehensive function of reason.

It is well recognized that we live now in an age of multiculturalism. As I see it, the concept of “multiculturalism” should mean, of course, but not only, a request for cultural identity and respect for cultural difference, as Charles Taylor seems to be contended with. Charles Taylor’s interpretation limits his own concept of multiculturalism to a kind of «politics of recognition ».[1] For me, multiculturalism means, of course, that each and every culture has its own cultural identity, and that we should respect each other’s cultural differences. But it should mean, above all, mutual enrichment by cultural difference and search for more universalizable elements embodied in various cultural expressions. We can attain this “upgraded” meaning of multiculturalism only through conducting dialogues between different cultural worlds.

With the realization of a global village, now we are witnessing the deepening of a historical process in which, as F. S. C. Northrop said, “The East and the West are meeting and merging. The epoch which Kipling so aptly described but about which he so falsely prophesied is over.”[2] In this situation, different ways of doing philosophy in different cultures could enrich our vision of Reality. Especially in this time of radical change, a new philosophy capable of tackling this challenge has to include in itself the intercultural horizon of philosophy.

But what is an intercultural philosophy? This should not be limited to only doing comparative philosophy, as in the cases of comparative religion, comparative linguistics…etc., which are often limited to the studies of resemblance and difference between different religions or languages. Although doing comparative philosophy in this manner could lead to relativism in philosophy, but it could not really help the self-understanding and practice of philosophy itself.

For me, the real objective of doing intercultural philosophy is therefore to put into contrast between, rather than sheer comparison of, different philosophical traditions. I understand « contrast » as the rhythmic interplay between difference and complementarity, continuity and discontinuity, thus leading to real mutual-enrichment of different traditions in philosophy.[3]

I propose a philosophy of contrast as alternative to both structuralism and Hegelian Dialectics. Structuralism sees only elements in opposition but not in complementarity. Also it overemphasizes synchronicity to the negligence of historicity. On the other hand, historical movement is essential to Hegelian Dialectics. Hegel sees dialectics as both a methodology and an ontology, that is, as the historical movement of reality. It moves by Aufhebung understood in a negative way, and tends finally towards the triumph of negativity, thus overlooks the positivity in dialectical movement. But my concept of contrast rediscovers both complementarity and historicity and integrates both negative and positive forces in the movement of history.

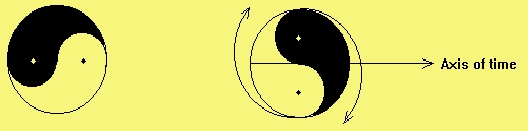

The wisdom of contrast has its origin in Chinese philosophy. For

example, the Book of Changes said, “The rhythmic

interaction between Ying and Yang constitutes what we call the

Way (Tao).” Also Lao Tzu in the Tao Teh King said

something similar to this: “All things carries Ying and

embraces Yang, and through their blending interaction they

achieve harmony.” The traditional representation of Tai Chi(

![]() ) can give us a

concrete image of philosophy of contrast (Figure 1). Apparently,

it represents only what I call “structural contrast.”

But we can put it into movement on the axis of time and thereby

we have the image of “dynamic contrast” (Figure

2).

) can give us a

concrete image of philosophy of contrast (Figure 1). Apparently,

it represents only what I call “structural contrast.”

But we can put it into movement on the axis of time and thereby

we have the image of “dynamic contrast” (Figure

2).

Figure 1. Figure 2.

By

“structural contrast” I mean that in any moment of

analysis, our perception, or any object under investigation, is

constituted of interacting elements, different yet related,

opposing yet complementing one with another. It is synchronic in

the sense that these elements appear simultaneously to form a

structured whole. Being different, each element enjoys a certain

degree of autonomy. Being related, they are mutually

interdependent.

On

the other hand, by “dynamic contrast” I mean that on

the axis of time, our individual life-story and collective

history are in a process of becoming through the interplay

between the precedent and the consequent moments. It is

diachronic in the sense that one moment follows the other on the

axis of time to form a history, not in a discontinuous succession

but in a contrast way of development. As discontinuous, the novel

moment has its proper originality never to be reduced to any

precedent moment. As continuous, it always keeps something from

the precedent moment as residue or sedimentation of experience in

time. Dynamic contrast could explain for example the relationship

between tradition and modernity.

In this

sense we are different from structuralism for which the structure

is anonymous and it determines the constitution of meaning

without being known consciously by the actor. For us, on the

contrary, a system or a structure is always the outcome of the

act of structuration by certain actor or group of actors in the

process of time.

But,

on the other hand, the process of time can also be analyzed

through static regard in order to uncover its structural

intelligibility. An historical action can be analyzed in terms of

systematic properties and be integrated into a structural whole.

This is especially true, for example, in communication where

system and agent are mutually dependent and promoting one

another. The contrasting interaction between structure and

dynamism leads finally to the evolution process of

complexification. Structural contrast puts interacting elements

into a kind of organized whole, but it is only through dynamic

contrast that continuity and emergence of new possibilities can

be properly understood.

A similar vision can be found in Paul Ricoeur’s

hermeneutics. Setting up the text as model for hermeneutics,

Ricoeur confers to the structural aspect of a text a certain

“semantic autonomy”, as resulted from the act of

distanciation. But every structure always calls for existential

interpretation by an actor, interpretation that creates a

dynamism in history as a form of co-belongingness. Distanciation

and co-belongingness are two moments in dialectical interplay

similar to the interaction between structural contrast and

dynamic contrast.[4]

The wisdom of contrast reminds us always to see the other side of the story and the tension between complementary elements essential to creativity in time. For example, the wisdom of contrast will remind us of the contrasting situation between concepts such as agent and system, difference and complementarity, continuity and discontinuity, reason and rationality, theory and praxis, understanding and translatability…etc.

Now, let’s consider what are the epistemological strategies we can adopt in view of an intercultural philosophy. Two consecutive strategies could be proposed here: First of all, the strategy of appropriation of language, which means more concretely learning the language of other traditions of culture and philosophy. Since, as Wittgenstein suggested, different language games correspond to different life-forms, appropriation of another language would give us access to the life-form implied in that specific language. By appropriating different languages of different cultural traditions, we could enter into different worlds and thereby enrich the construction of our own world.

Second, the strategy of strangification, which was in the beginning proposed by Fritz Wallner as an epistemological strategy for interdisciplinary research, but I would propose to enlarge it into the intercultural context and thereby it becomes a strategy of intercultural philosophy. By “strangification” I mean the act of going outside of oneself and going to the other cultural context, to the stranger’s culture. In other word, in doing intercultural philosophy, we have to translate the main theses or rationale of one’s own philosophical tradition into a language understandable to other philosophical traditions, so as to make it universalizable. If the main theses or the rationale of one philosophical system or philosophical tradition could be translated into language understandable to other traditions, and thereby become universalizable, we could say that it contains more truth-content in itself. If it could not be translated, this means it is in some way or other limited within itself, and should therefore submit itself to critical examination through self-reflection, in respect to its own principle as well as its methodology. [5] Language appropriation and strangification are thereby two epistemological strategies to be adopted by intercultural philosophy.

In the following, I will first of all try to put European philosophy and traditional Chinese philosophy into contrast on different levels of analysis. Then I will try to work out some important philosophical concepts for intercultural philosophy.

In the beginning, Western philosophy can be traced back to its origin in the Greek notion of theoria, the disinterested pursuit of truth and sheer intellectual curiosity.[6] Compared with this, Chinese traditional learning in general and Chinese philosophy in particular seemed to be short of such a theoretical interest and was more pragmatically motivated. Generally speaking, Western epsteme, began as a result of the attitude of wonder, which led to the theoretical construction of scientific and philosophical knowledge; whereas Chinese learning and philosophy began with the attitude of concern, which led finally to a practical wisdom for guiding human destiny. Therefore, in the beginning, the difference between these two origins was a difference between theoria and praxis.

In the case of Western science, Aristotle pointed out in Metaphysics

that the way of life in which knowledge began was constituted of

leisure (rastone) and recreation (diagoge), for

example as in the case of Egyptian priests who invented geometry

in such a way of life. Aristotle believed that in leisure and

recreation, human being needed not to care about daily

necessities of life and could wonder about the causes of things

and search knowledge for knowledge’s own sake. The result of

wonder was theories. Aristotle wrote in Metaphysics:

“For it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize; they wondered originally at the obvious difficulties, then advanced little by little and stated difficulties about the greater matters,...therefore since they philosophized in order to escape from ignorance, evidently they were pursuing science in order to know, and not for any utilitarian end.”[7]

According to Aristotle, the philosophical meaning of “theory”, was determined on the one hand with respect to praxis, as Aristotle put it, “not in virtue of being able to act, but of having the theory for themselves and knowing the causes.”[8] ; on the other hand, with respect to a universal object, which was seen by Aristotle as the first characteristic of episteme,[9] thus leading to philosophy and ending up with ontology.

As we know well now that the emergence of theoria in Greece had its religious origin. In the beginning, theoros were the representatives from other Greek cities to Athens’s religious ceremonies. It was through looking at, and not taking action, that they participated in religious ritual. Furthermore, philosophy as resulted from theoria, instead of looking at the alter or stage of performance, philosophers looked on the universe in a disinterested way. Western philosophy was historically grounded in this Greek heritage of theoria, which regarded our human life no longer as determined by diverse practical interests, but as submitted itself henceforward to a universalizing and objective norm of truth. Theoria and philosophy, in Aristotle’s Metaphysics, culminate ultimately in ontology, which according to Aristotle investigates being as being (to on he on), as the most general and comprehensible aspect of all beings.

By contrast, Chinese philosophy in general was originated as a result of the attitude of concern, which led not to universalizable theorization but to universalizable praxis. It was because of his concern with the destiny of individual and society that a Chinese mind began to philosophize. The Great Appendix to the Book of Changes, attributed traditionally to Confucius, proclaimed that its author must be facing anxiety and calamity with compassionate concern. Here we read:

“Was it not in the last age of Yin, when the virtue of Chou

had reached its highest point, and during the troubles between

King Wen and the tyrant Dzou, that the study of Changes began to

flourish? On this account the explanations in the book express a

feeling of anxious apprehension, and teach how peril may be

turned into security, and easy carelessness is sure to meet with

overthrow. The way in which these things come about is very

comprehensive, and must be acknowledged in every sphere of

things. If in the beginning there is a cautious apprehension as

to the end, there probably will be no error or cause for blame.

This is what is called the Way of Changes.” [10]

This text shows that in the eyes of Confucius, philosophy as a serious intellectual activity began with a concernful attitude in the situation of anxiety and calamity, not at all in the situation of leisure and recreation, as Aristotle seemed to suggest. The proposition that “the way in which these things come about is very comprehensive, and must be acknowledged in every sphere of things” would suggest that Chinese philosophy intended to be a practical wisdom that could serve as guidance for an universal, or at least universalizable, praxis.

But notice here that the term « universalizable » shows us also a convergence between Western philosophy and Chinese philosophy: both of them are concerned with the universalizable aspect of their truth. Even if Western philosophy concerns more with the universality or universalizability of theories, whereas Chinese traditional philosophy concerns itself more about practical universalizability, nevertheless both of them try to criticize particular interest and to transcend the limit of particularity, in view of attaining the universalizability. Even if the question about whether there is universality pure and simple could still be debated, still this effort of criticizing particularity and of going from particularity to universality, might we call it the process of universalization, is common to both Chinese philosophy and Western philosophy.

Now let me proceed to put into contrast the epistemological aspect of both Western philosophy and Chinese philosophy. This part of contrast leads us from Greek philosophy to modern Western philosophy and science. The development of Western modern philosophy, which cherished the primacy of epistemological reflections, gives us an occasion to compare Western philosophy and Chinese philosophy, especially concerning their epistemological principles.

First, as we know well, rationalism since Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz…etc., has founded the rational side of modern European science. Geometry, algebra or more generally, Mathesis Universalis had well founded the rational side of modern European science, which is also a process of theory-construction using logical-mathematically structured language to formulate human knowledge.

Compared with this, Chinese traditional learning in general is quite different by the fact that it did not utilize logico-mathematic structure for theory formation. It had never pondered upon its own linguistic structure to the point of having elaborated a logic system for the formulation and control of scientific discourse. Mathematics, although highly developed in ancient China, was used only for describing or organizing empirical data, not for formulating theories. Lacking in logical mathematical structures, Chinese quasi-scientific theories were principally presented through intuition and speculative imagination. They might have the advantage of being able to penetrate into the totality of life, nature and society to give them reasonable interpretation, but these “theories” lacked somehow the rigor of structural organization and logical formulation.[11]

Second, the classical empiricism of Lock, Berkeley, Hume…etc., has founded the empirical side of Western Modern science, characterized by its well-controlled systematic experimentation. By elaborating on the sensible data and our perception of them, it assures itself of keeping in touch with the Environment, the supposed “Real World”, but in an artificially, technically controlled way.

In contrast, the “empirical data” in Chinese traditional sciences were established through very detailed but passive observations, with or without the aid of instruments. But it had seldom tried any systematically organized experimentation to the extent of effecting any active artificial control over human perception of natural objects.

Third, in Western modern epistemology, there is a conscious checking of the correspondence between the rational side and the empirical side in order to combine them into a coherent whole to serve human being’s objective in explaining and controlling the world. Either in the tradition from classical empiricism to Logical positivism which assumes that there is truth when there is correspondence of theory to empirical data, or in Kant’s manner that the world of experience must enter into the framework of our subjectivity in order to become known by us. Philosophical reflection, in checking the correspondence between these two aspects, assures us of their coherence and their unity.

Concerning the mode of relation between empirical knowledge and their intelligible ground of unity, Chinese traditional learning had not conceived of any interactive relation in the mode of falsification, verification, or confirmation. Although Chinese traditional learning did have its proper visions of science and knowledge in general, it did not have that type of epistemological reflection and philosophy of science which consists in checking the nature of and the correspondence between the empirical constructs and the rational constructs as in the case of Western modern science.

But we should say that still there existed some sort of unity in traditional Chinese learning. [12] For example, in the case of Confucianism, Once Confucius put the question to his disciple Tzu Kung:

“You think, I believe, that my aim is to learn many things and retain them in my memory?”

Tzu Kung replied, “Is that not so?”

The Master replied, “No, there is an unity which binds it all together.”[13]

Confucius seemed to affirm, as Kant did, the complementary interaction between empirical data and thinking. He said, “He who learns without thought is utterly confused. He who thinks without learning is in great danger.”[14] These words of Confucius remind us of Kant’s proposition that sensibility without concept is blind, whereas concept without sensibility is void.

But we should be clear here that the mode of unity in traditional Chinese science was a kind of mental integration in referring to the Ultimate Reality through the process of ethical praxis. Here “praxis” or “practical action” was not interpreted as a kind of technical application of theories to the control of concrete natural or social phenomena. It was understood rather as an active involvement in the process of realizing what is properly human in the life of individual and that of society. As to science and technology, they are not to be ignored but must be reconsidered in the context of this ethical praxis.

Now, let me shift to a discussion on the function of reason, though still in connection with epistemological discussion. Here I want to point out that the function of reason in Chinese philosophy is characterized by its reasonableness rather than rationality. From the above analysis, it is difficult to characterize traditional Chinese Learning in general and Chinese philosophy in particular as rational in the sense of Western science. They were rather reasonable in the hermeneutic sense. To be scientifically rational, Chinese traditional learning would be obliged to follow the model of modern Western science, that is, to appeal to Mathesis Universalis and empirical data, and to establish their correspondence through well-controlled interaction process. But to be reasonable, it would be better to refer to the totality of existence and to its meaningful interpretation by human life as a whole. In this perspective, we could say that traditional Chinese learning as a whole tended always to be reasonable, while neglecting its own potentiality in scientific rationality.

Rationality in Western modern science envisages the systematic enlargement of our knowledge through the controlling procedures of theory formation and experimentation. For example, in the case of natural sciences, theories are presented either through steps of generalization or as outcomes of creative scientific imagination, and are then extended to new domains of experience through experimentation. Since the main theoretical instrument of natural sciences is theoretical language, the progress of natural sciences depends much on the construction and development of their theories. But it is also very important to control the validity of these theories. This is normally done by the procedures of experimentation which consist of identifying a specific phenomenon in order to effect what K. Popper called as either corroboration or falsification of the theory in question. In other words, experimentation not only is the way by which natural sciences extend their theories to new domains of experience, it is also a way of controlling the validity of theories.

Since the above procedures are quite operational in kind, the cognitive side of scientific rationality is now very much related to its practical side. Although Western modern science, in its origin, was very much related to the Greek theoria, it is now related to action by the technical aspects of experimentation and the practical aspect of industrialization, even to the point of neglecting or even forgetting its original spirit of theoria.

On the practical side, science also has a deep involvement in action. It changes the construction of language meaning as well as that of the states of affairs through its operational character. We have to point out here that, on the one hand, the operation of formal reasoning and calculation in the logical structure of theories have transformed the meaning of language into an abstract and structural setting. On the other hand, the operation of experimentation intervenes also into the construction and organization of the states of affairs in specific context of space and time.

Generally speaking, the practical side of scientific rationality could be analyzed by the mutual relationship between means and end. Under the constraint of logical reasoning and calculation, this kind of rationality could be entitled, in the first instance, as “strategic rationality”, when in calculation it envisages logical connections between possible actions. In other word, it analyses an action of grand scale into smaller but feasible actions and then relates them together by systematic logical connection. It could also be characterized, in a second instance, as “instrumental rationality”, when in experimentation or in application to technology it judges the problem of whether one action is rational or not only according to the criteria of efficiency, that is, the efficiency of utilizing a certain means by which we can attain the envisaged end.

As to reasonableness, on its cognitive side, reasonableness concerns the dimension of meaning: meaning of a literary or artistic work, meaning of a human behavior, meaning of a social institution, meaning of a certain culture...etc. The model of this cognitive activity could be found in the understanding and interpretation of a text. This activity of understanding and interpretation is quite universal for mankind in the sense that it could be extended to any form of relationship that human beings entertain with the dimension of totality of existence.

In the understanding of meaning, we have to refer, not only to its linguistic meanings, but also to the totality of my Self and the totality of relationships that I entertain with the world. In some sense, it has to start from myself as subject of my experience and my understanding in order to reconstruct the meaning of a text. This echoes Edmund Husserl’s thesis that the constitution of meaning refers inevitably to the intentionality of he who understands. But we could also say with Heidegger that we understand when we grasp the possibilities of existence (Seinskönnen) implied in the text. In our understanding of the meaning of existence, there is also an ontological dimension in which truth reveals itself as the manifestation of Being in our understanding.

On its practical side, when we ask the question what are those actions which are subject to the function of reasonableness, the answer is that all actions concerned with subjective choice and personal as well as collective involvement in meaning constitution. For example, we could think of those actions concerned with the creation and appreciation of works of art, with the realization and evaluation of moral intention, and even those political actions concerned with the decision of historical orientation of a certain social group. All these kinds of actions are to be determined by reasonableness.

We have to notice that, the first element of reasonableness which refers itself to the totality of one’s Self and that of the relation between the Self and the world, is still quite limited to human-centered orientation. The second element of hermeneutic reasonableness has a more speculative tendency. It concerns more with the totality of Being and is not limited to human subjectivity, human experience and human meaningfulness.

Reasonableness is therefore caught in the tension between the reference to the totality of one’s Self and the reference to the totality of Being. In Chinese philosophy, Confucianism insists upon the necessity to refer to the totality of human existence, whereas Taoism points out the necessity to get out of the human-centered tendency of Confucian humanism and to refer rather to the totality of Being exemplified by the concept of Tao.

First, Confucianism is a system of reasonable ideas which refers ultimately to the totality of human existence and its realization as the horizon within which the meaning of human actions, and even that of natural phenomena, is to be contextualized. With this spirit of reasonableness, Confucianism has established some principles of reasonableness upon which more particular function of human reason, such as rationality in science and technology, could base itself for more healthy use. Confucian reasonableness refers to the totality of human agent and his relation with the world.

Confucius himself lived in a period of time of political and

social disorder. Confucius tried to revitalize social order by

proposing first the concept of jen(![]() ), which signified and represented the

sensitive interconnectedness between human being’s inner

self with other human beings, with nature and even with Heaven. Jen

manifests human subjectivity and responsibility in and through

his sincere moral awareness, and in the meanwhile, it means also

the intersubjectivity giving support to all social and ethical

life. That's why Confucius said that “Jen is not

remote or difficult to Human beings, only when an individual will

for it, jen is there in himself.” By proposing the

concept of jen, Confucius had laid a transcendental

foundation to human being’s interaction with nature, with

society and even with Heaven.

), which signified and represented the

sensitive interconnectedness between human being’s inner

self with other human beings, with nature and even with Heaven. Jen

manifests human subjectivity and responsibility in and through

his sincere moral awareness, and in the meanwhile, it means also

the intersubjectivity giving support to all social and ethical

life. That's why Confucius said that “Jen is not

remote or difficult to Human beings, only when an individual will

for it, jen is there in himself.” By proposing the

concept of jen, Confucius had laid a transcendental

foundation to human being’s interaction with nature, with

society and even with Heaven.

Then, from the concept of jen, Confucius deduced the

concept of yi (![]() ), righteousness, which represented for him the respect for and

proper actions towards the other. Righteousness is also the

criterion by which are discerned a good man and a base guy. On

righteousness was based all moral norms, moral obligations, our

consciousness of them, and even the virtue of always acting

according to them.

), righteousness, which represented for him the respect for and

proper actions towards the other. Righteousness is also the

criterion by which are discerned a good man and a base guy. On

righteousness was based all moral norms, moral obligations, our

consciousness of them, and even the virtue of always acting

according to them.

From the concept of yi, Confucius deduced the concept of li

(![]() ), ritual, which

represented the ideal meaning and practical codes of behavior,

political institutions and religious ceremonies. You Tzu, one of

Confucius’ disciples, said that "The function of ritual

consists best in harmony." Li, ritual, as an overall

concept of cultural ideal, means a graceful order leading to

harmony.

), ritual, which

represented the ideal meaning and practical codes of behavior,

political institutions and religious ceremonies. You Tzu, one of

Confucius’ disciples, said that "The function of ritual

consists best in harmony." Li, ritual, as an overall

concept of cultural ideal, means a graceful order leading to

harmony.

In short, for Confucianism, the dimension of meaning in human existence is therefore to be understood within the context of totality, defined by the system of ideas constituted of jen, yi and li.

But with Taoism, the perspective of reasonableness changes quite differently. Taoism, especially when presented by its primordial thinkers, Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, emerged with a vehement critique of Confucianism’s anthropocentric interest. Lao Tzu proposed, instead of Confucian jen, a mindless spontaneous creativity coming exhaustibly from Tao itself as the ontological ground upon which a meaningful human existence should base.

The concept of “Tao” originally signified ways followed

by human beings. It could also mean ways out for social,

political, and even spiritual crisis. But these were not what it

meant for Lao Tzu, who would rather push the meaning of Tao to

the extreme of speculative thinking. It means thereby the Way

itself, the Ultimate Reality. In Taoism, the concept of Tao

represents something like Heidegger’s self-manifesting

Being. Tao, when manifested itself in myriad things, still live

in them and thereby become the spontaneous creativity of each and

every being, including human beings. This spontaneous creativity

of every being, the Tao in each one of us, is called by Lao Tze

as teh(virtue), not virtue in moral sense as Confucianism

would think, but virtue as innate capacity or spontaneous

creativity. Tao and teh are the really real reality, not

merely concepts, because treating Tao and teh as mere concepts

would reduce them to the status of a mere conceptual being, or

ens rationis, and therefore to an ontic status. This is what Lao

Tzu meant when he said, “The Tao that could be told of is

not the eternal Tao; the name that can be named is not the

eternal name.”[15]

The case of Taoist philosophy shows that, reasonableness, as the function of reason to understand itself in referring to the totality of Being, Tao, is also an exploitation of human reason itself to its extreme limit and to attain thereby self-understanding.

In short, Taoist philosophy, as a philosophy referring to Tao and the totality of Being, and Confucianism, as a philosophy referring to the totality of human existence, exemplify two complementary aspects of Chinese reasonableness.

Now I want

to turn to some concepts fundamental for an intercultural

philosophy. I would suggest first the distinction and relation

between Reality Itself, Constructed Reality and Life-world. I

think it is a basic truth to look on the Reality represented in

our knowledge and language as a kind of Constructed Reality,

which is different from the Reality Itself, though both have to

be mediated and realized by us humans in the Life-world, in which

our culture is situated. [16]

Each discipline of science or research program constitutes a micro-world of its own because of the particular methodology and language its uses and the life-form it’s language game corresponds to. We use the term “Constructed Reality” to designate the essential attribute of each micro-world as well as the sum total of all micro-worlds.

Further, when I say that there is Reality Itself, I do not mean by that a Ding an Sich in the philosophy of Kant or an unfathomable noumenon foreign to all human understanding. Nevertheless, all our scientific, cultural and everyday activities presuppose Reality Itself as the environment in which they take place and the ontological ground in which we live, act and know and that everything happens. This is just what I mean by Reality Itself.

As to the concept of Life-world, I mean by this concept the cultural world together with the natural world, in which we human beings lead our every day life. It is constituted of Constructed Reality, because of our scientific and language constructions, and of Reality Itself, because of its grounding in the natural and cosmic process. Because of the fact that in human Life-world there exist the double process of transforming Reality Itself into Constructed Reality and reference to Reality Itself in human production of Constructed Reality, Life-world should be considered as the horizon in which we humans mediate Constructed Reality and Reality Itself.

In Chinese philosophy, it is necessary to ask the question about the relation we have with Reality Itself. I would say that Chinese culture is characterized by its intimacy with Reality Itself. It cherishes always communicative union with the Reality Itself, understood as Tao, as Nature or as Life. It recognizes the fact that all our knowledge and language are but human construction, to the extent that we should deconstruct them in order to let the Reality manifest itself. Deconstruction, in order to go beyond all human constructions, so as to let Reality manifests itself.

We can see this particularly in the case of Taoism, which since 25 Centuries before had made the distinction between Reality Itself and Constructed Reality. Lao Tzu said that “Tao could be said, but that which is already said about Tao is not the Tao Itself.”[17] The distinction between “Tao Itself” and “Tao said” corresponds to the distinction between Reality Itself and Constructed Reality. Though, in Taoism, this distinction is posited, on the one hand, to point out the necessity of tracing back the origin of Constructed Reality’s to Tao, Reality Itself. On the other hand, this distinction points out also the insufficiency of all our languages, rather than the overwhelming power of language.

For Taoism, Tao manifests itself in Nature, and Nature is seen as a spontaneous process not to be dominated and determined by human being’s technical intervention. Human beings are considered by Taoism as only part of nature, whose ontological status are just like plants, animals and others beings in nature, all taken to be sons of the same Mother, Tao. This vision of relation between human beings and Nature is very different from modern science and technology. Modern science defines “nature” as the totality of phenomena to be explained and predicted by natural laws, and modern technology treats “nature” as the totality of material resources to be manipulated and transformed by technical process. The consequence of this concept of nature today is serious ecological disequilibrium, pollution and other environmental problems, even to the menace of human existence.

But Taoism teaches us how to respect the spontaneous process of nature. Human being’s knowledge should be constructed in such a way that it unfolds the spontaneous dynamism of nature.[18] He should avoid human-centered or even ego-centric construction of knowledge. This Taoist position is more ecological and it tends to construct knowledge and Umwelt in a more natural way. According to Taoism, human beings should not construct knowledge for construction’s sake, on the contrary, we should construct in such a way that it manifest the structure and dynamism of Nature Itself.

According to Taoism, human being should be aware of the limit of language and keep his mind open to the spontaneous dynamism of nature. Human being should construct his knowledge and Life-world, not according to the structural constraint of his language, but according to the rhythmic manifestation of nature. Micro-worlds as constructed by different disciplines and languages, and even the Constructed Reality as the sum total of all micro-worlds, should not be taken for the Life-world. Chinese culture cherishes the Life-world, which is partly constructed by human beings, partly unfolding itself spontaneously in the rhythm of nature.

On the other hand, Confucianism would look on human beings as the center of cosmos, who nevertheless are open to the dynamism of nature. This openness is based upon the fact that human beings are interconnected with and responsive to others, to nature and Heaven. This responsiveness, this interconnectedness, which Confucianism expresses by the term “jen”, serves as the ontological foundation of the manifestation of Reality Itself and human’s original communicative competence.

Confucian philosophy of language is somehow different from that of Taoism. According to Confucianism, language, as human linguistic construction of reality, should also be seen as mode of manifestation of Reality Itself. This could be achieved through semantic correctness and sincerity of purpose. Contrary to Taoist critique of science and technology, Confucianism would look upon science and technology as capable of being integrated into the process of constructing a meaningful world. The process of human intervention into the process of nature is seen by Confucianism as humankind’s “participation in and assistance to the creative transformation of Heaven and Earth”. Confucianism proposes a kind of participative construction instead of dominative construction. This term of “participative construction” could also applied to Taoism, in the sense that for the Taoists, all human technical intervention should be promoted by Tao and act according to the rhythm of nature itself, in order to le manifest the creative dynamism of both human nature and physical nature.

Today we are worrying about that fact that our scientific and technological construction of the world is going to the worse side, to the deterioration of our Life-world. It is now pertinent to listen to Taoism and Confucianism for which the process of human construction should go to the better and not to the worse. But what is the criteria for judging the better construction from the worse? Taoism and Confucianism would say that the criteria lies in the principle that human construction of Lebenswelt should participate the creative rhythm of Nature (Heaven and earth), not to dominate it. Therefore both Taoism and Confucianism distinguishes participative construction from dominative construction. Human construction of the Life-world should be the participative one, not the dominative one.

In the beginning, I have spoken about the strategy of strangification, which, I would assume, is most important for this world of pluralism. We are facing now not only multidiciplinarity, but also muticulturalism, not to mention the more and more conflicting differences in interests, ideologies and worldviews. In this pluralistic world, the search for self-identity, for respect of difference and for mutual enrichment become more and more urgent. Except in the domain of artistic creation, where there will be no space for compromise and consensus, and there we can accept Jean Francois Lyotard’s suggestion of a radical respect for difference in language games in view of originality and creativity. But in the public sphere, in any case, we always need more communications and more effort for consensus. Because, in the public sphere, life could not go without communication, and policy making could not be made without consensus.

I accept

Lyotard’s view that we should respect each language game and

their differences. But this does not mean that we should not try

to understand other’s language game and to appropriate it or

to translate ours into language understandable to others.

Otherwise we will not be able to really appreciate the difference

of the other, and our respect for his difference is deprived of

an authentic appreciation of it. In fact, if a person P can

really say that language game A is in such and such aspects

different from language B, even to the degree of incommensurable,

it means that both language games are intelligible and

understandable to P and P understand them thereby, the fact of

which presupposes that P’s appropriation of both languages

and his execution, at least implicitly, of strangification

between them.

That’s

why I consider Lyotard’s respect for different language game

remains very abstract. In order to understand other’s

difference, the language appropriation and strangification are

needed, and these do not necessarily presuppose any tentative of

unification. Strangification presupposes, methodologically

speaking, language appropriation, but it does not presuppose the

finality of unification. Not to appropriate other’s language

and no will for strangification means enclosure within one’s

own micro-world or cultural world.

The concept of strangification (Verfremdung) could be seen as a new paradigm of communication between different parts. Although it is proposed first by Fritz Wallner of Vienna University[19] to envisage the need of an epistemological strategy for interdisciplinarity in science, the strategy of strangification, according to me an act of recontexualization, of going out of one’s own cognitive context into the context of strangers, of others, could be applied to all kind of communication, even to cultural interaction and religious dialogue.

There are three types of strangification: the first is linguistic strangification, by which we translate from one language in the context of one particular discipline or culture into the language of other discipline or other culture, to see whether it works or it becomes absurd thereby. If in the latter case, reflection must be done concerning the methodology and principles in the first language.

The second is pragmatic strangification, by which we draw one scientific proposition or cultural value from one social, organizational and cultural context, to put it into another social, organizational and cultural context in order to make clear its pragmatic implications and to enlarge its social and organizational possibilities.

The third is ontological strangification, which, according to Fritz Wallner, is the movement by which we transfer from one micro-world to another micro-world. But for me, there is ontological strangification when we appeal to the ontological condition of science and culture or we move from one micro-world or cultural world in to another micro-world or cultural world through the detour of contact with or the manifestation of Reality Itself.

Among the three, the basic strategy is linguistic strangification, by which one translate propositions or cultural values from one micro-world or cultural world into other language understandable to other micro-world or cultural world. Even if in the process of translation, we loose by necessity some meaningful content, especially in the case of aesthetic values, moral values and religious values, this should not be an excuse for not doing any effort of strangification. We should not argue from the fact of loosing meaning in translation for a radical intranslatability of different language games. We could say that there must be a minimum of translatability among different language games, so as to permit the act of strangification. The act of strangification presuppose also the will to strangify and the effort of strangification. No will to strangify and no effort of strangification would mean simply the enclosure in one’s own micro-world or cultural world. Strangification is the minimum requirement in interdisciplinary and intercultural situations.

I would say that strangification is a very useful strategy, not only for different scientific disciplines, but also for different cultures. It is even more fundamental than Habermas’ concept of “communicative action”. In fact, Habermas’ communicative action is a process of argumentation in which the proposition-for and the proposition-against, by way of Begründung, search for consensus in a higher proposition acceptable for both parties. Although Habermas has proposed the claims for an ideal situation of communication such as understandability, truth, sincerity and legitimacy, unfortunately in the actual world of communication, there happens very often either total conflict or compromise, without any real consensus. The Habermasian argumentation tends to fail if in the process of Begründung and in the act of searching for consensus, there is no first of all an effort for strangification. In this case, there will be no real mutual understanding and no self-reflection during the process of argumentation. Therefore, the strategy of strangification could be seen as prerequisite for any successful communication and coordination.

Philosophically speaking, the strategy of strangification has its condition of possibility in human communicative competence. In Chinese philosophy, Confucianism would propose jen as the original communicative competence, the ontological condition of possibility which renders feasible and legitimate the act of strangification as well as communication and self-reflection. From this original communicative competence, Confucianism propose the concept of shu, which could be seen as an act of empathy and strangification, which is a better strategy for fruitful communication than Habermas’ argumentation. Confucianism, in positing the existence of a “sensitive responsiveness” as condition of possibility to strangification, has elevated strangification to the ontological level. According to Confucianism, there is ontological strangification when we conduct strangification upon our responsive interconnectedness with others.

The Confucian liang chi(![]() ) and its tacit consensus could serve as the

pre-linguistic and therefore tacit basis for argumentative

consensus. Also, during the process of argumentation, because of

the difference in political languages and in concepts such as

truth, sincerity, legitimacy…etc.,, Habermas’

suggestion of four ideal claims would not work in actual

political debates, to the point of leading towards total

conflict. The Habermasian argumentation tends to fail if in the

process of Begründung and in the act of searching for consensus,

there is no first of all an altruistic effort of empathy and of

using language understandable to others. There will be no real

mutual understanding and no self-reflection during the process of

argumentation, if we do not communicate our position in

considering for the others and speaking the other’s

language.

) and its tacit consensus could serve as the

pre-linguistic and therefore tacit basis for argumentative

consensus. Also, during the process of argumentation, because of

the difference in political languages and in concepts such as

truth, sincerity, legitimacy…etc.,, Habermas’

suggestion of four ideal claims would not work in actual

political debates, to the point of leading towards total

conflict. The Habermasian argumentation tends to fail if in the

process of Begründung and in the act of searching for consensus,

there is no first of all an altruistic effort of empathy and of

using language understandable to others. There will be no real

mutual understanding and no self-reflection during the process of

argumentation, if we do not communicate our position in

considering for the others and speaking the other’s

language.

In Confucianism, the concept of shu (![]() ) represents this ability to go to the

other in an sympathetic way and to communicate with him through

language understandable to him. Especially under the postmodern

condition, when any difference in race, gender, age, class and

belief system will create total conflict, any part in difference

should communicate with other parts with the spirit of shu

(

) represents this ability to go to the

other in an sympathetic way and to communicate with him through

language understandable to him. Especially under the postmodern

condition, when any difference in race, gender, age, class and

belief system will create total conflict, any part in difference

should communicate with other parts with the spirit of shu

(![]() ), together with the

acts of empathy and strangification.

), together with the

acts of empathy and strangification.

On the other hand, from the Taoist point of view, strangification presupposes not only appropriation of and translation into other languages. It is also necessary to render oneself present to the Reality Itself. In Lao Tzu’s word, “Having grasped the Mother (Reality Itself), you can thereby know the sons (micro-worlds). Having known the sons, you should return again to the Mother.”[20] Taoism posits an ontological detour to Reality Itself as condition sine qua non for the act of strangification into other worlds (micro-world and cultural world).

In terms of Lao Tzu, we understand the Reality Itself by the process of a “retracing regard”(kuan), an act of intuition of essence of things by letting things what they are. The process of formation of our experience is therefore seen by Taoism as a process of back and forth between the act of interacting with micro-worlds (sons) and the act of returning to Reality Itself (the Mother). The act of returning to Reality Itself and communicating with it is therefore considered by Taoism as nourishing our strangification with other micro-worlds. This act of ontological detour to Reality Itself bestows an ontological dimension to strangification. Ontological strangification in this sense is especially important for religious dialogue, when the relation with the ultimate reality is most essential to religious experiences.

This concept of ontological detour in Chinese philosophy is very suggestive not only in cultural and religious dialogue. I would point out also the fact that, according to the philosophy of contrast, which has it’s root in the philosophical wisdom of Confucianism and Taoism, the micro-worlds are in a situation of contrast. In the act of strangification and in the act of constructing Reality, various micro-worlds and cultural world, though different, are in the meanwhile complementary. This ontological situation renders necessary the act of strangification. Furtheremore, the original communicative competence, the responsive ability, as exemplified in Confucian concept of jen, serves as the ontological condition of possibility of the act of strangification. In other words, it makes strangification possible.

Finally,

I will speak a few words about action. Because all discourses

lead finally to action, this is not only true in the case of

science, but also in the case of culture and especially

intercultural interaction. Scientific construction, cultural

construction, and the act of strangification among

different sciences and cultures, all belong to the domain of

action. That’s why the philosophy of pragmatism is now quite

pervasive in the domain of science, interdisciplinary research

and intercultural interaction.

“Pragmatism” means a way of thinking which attaches itself to the dimension of human action(pragmata). But, in our philosophical reflection, we should ask this question, what are the criteria of action in science and culture? It is not enough to judge by the Criterion of efficiency. Although efficiency is important for measuring science, it fails in the domain of culture. The criterion of efficiency falls under the category of instrumental rationality. In the case of modern Western science and technology, the excessive and abusive use of instrumental rationality has led to man’s exploitative domination over nature and society. This is against the principle of conserving and constructing a better Life-world.

For me, a serious danger for science and technology today is that they are now loosing their ideal. It has no long term goal for development. Science needs to renew some ideals to serve as idealizing incentives for its own actions. Otherwise, science and technology are falling down more and more into the darkness of nihilism, in which human beings has no ideal values for his existence and thereby becomes meaningless. To help humankind go through this nihilist valley of darkness, we should work out an ideal dimension or criteria of action for the future development of science and culture.

In Chinese philosophy, two other kinds of criteria are more important, ethical criteria and ontological criteria.

1. Ethical criteria: This means criteria which refer to ethical norms of action and to the ethical responsibility of human beings. It is the kind of criteria that Confucianism would emphasize. According to Confucianism, there are three most important ethical norms for human action.

First, all human action should be conducted in such a way that it leads to the fulfillment of human potentiality.

Second, all human action should be conducted in such a way that it leads to the unfolding of the object acted upon, either under scientific investigation or outcoming from cultural creativity.

Third, action should be conducted in such a way that it leads to the harmonization of relationship between humans, between humans and nature.

2. Ontological criteria: As suggested by Taoism, human actions should be conducted in such a way that it is not human centered, but to be situated in the global context of nature and Tao. In other words, action should be conducted in respecting the dynamism of nature and in serving for the manifestation of Tao, Reality Itself. In this way, it is no particular action. Compared with any ontic and dominative action, it is rather a kind of non-action, but by which nothing is left undone.

As I see it, now when we are facing the end of this Century and

the coming of the 21st Century, philosophy has three

most important issues to tackle with:

First, the swift and enormous development of science and

technology soon will become the leading factors of human

historicity and cultural development. How to deepen and not to

make shallow the development of science and technology through

philosophical reflection and to elaborate ethical reflection to

make science and technology human will be very important issues

in the future of human culture.

Second, the more and more frequent and intimate interaction

between different cultures will lead us ever since to a world of

multiculturalism. How to enrich ourselves and promote each other

through cultural interaction in which we share with others the

best part of ours and be aware of our own limitations through

contrasting with others. This task become more and more urgent in

the future. In this sense I think the intercultural philosophy is

a key to the future.

Third, as we have seen, the philosophy of this Century is too

much human centered. Just think of phenomenology, existentialism,

structuralism, critical theory, neo-Marxism, hermeneutics,

post-modernism, contemporary neo-Confucianism….etc.,...etc,

all these philosophical tendencies are too much human centered.

But as we can observe, the difficulties of humankind become

unsolvable in the bottleneck jammed with all these human centered

ways of thinking. Fortunately, the ecological movement and new

discoveries in astronomic physics leads us too much more concern

with Nature, and the religious renaissance in the end of this

Century lead us also to a concern with the transcendent or the

absolute other and also with inter-religious dialogue. Next

Century, we will have to redefine human experience in the context

of nature and inter-religious dialogue.

In identifying myself very much with the idea of an intercultural

philosophy, I propose here, inspired from my understanding of

both Western and Chinese philosophies, to extend the philosophy

of contrast, the philosophical distinction and relation between

Reality Itself, Constructed Reality and Life-world, and the

strategy of strangification, to the domain of these three

problematic: the relation of science and technology to culture,

the situation of multiculturalism and the redefinition of human

experience in both cosmic and in inter-religious context. This

will bring us to the challenge of next Century to intercultural

philosophy.

[1]Charles Taylor, Multiculturalism,

edited and introduced by A. Gutmann, (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1994), pp.25-36

[2]F.S.C. Northrop, The Meeting of East and

West, Woodbridge; Ox Bow Press, 1979, p.4.

[3]I have worked out a philosophy of contrast

in my works, especially in my Essays in Contemporary

Philosophy, (Taipei, Lih-ming Publishing Company, 1985)

[4] P.Ricoeur, Hermeneutics and the Human

Sciences, edited, translated and introduced by J.B.Thompson,

London: Cambridge University Press, 1981, pp.145-162; Cf.

V. Shen, "The Problem of Meaning in Narrative and Ricoeur's

Hermeneutics”, in The Journal of National Chengchi

University, Vol.48, Taipei,1983,pp.33-49.

[5] Here we have to notice the contrasting

relation between translatability and understanding. Translation

presuppose always understanding, and understanding should be

spoken out in one’s one language, as we could see in

Gadamer’s concept of application. Even if Gadamer in his Wahrheit

und Methode explains that understanding is quite different

from translation, and for me the horizon opened by understanding

exceeds really translation, nevertheless understanding itself

needs to be articulated by translation, otherwise if anyone takes

understanding and translatability in radical opposition, he will

necessarily against the concept of application.

[6]Vincent Shen, Disenchantment of the World.

Taipei: China Times Publishing Co., 1984, pp.31-37.

Reviewed new edition by Taiwan Commercial Press, 1997.

[7]Aristotle, Metaphysics, 982b 12-22.

[8]Aristotle, Metaphysics, 981b 6-7.

[9]Ibid., 982a 3-10,20-23.

[10]The Text of Yi Ching. Chinese

original with English translation by Z.D.Sung, Shanghai, 1935,

p.334.

[11]Joseph Needham suggests, “Mathematics

was essential, up to a certain point, for the planning and

control of the hydraulic engineering works, but those professing

it were likely to remain inferior officials Joseph Needham, Science

and Civilization in China. vol. II, p.30.For me, this social

and political reason given be Needham explains partly the

unimportance of mathematical discourse in Confucianism. More

internal reason of it might be that mathematics was considered as

technique of calculation and instrument of organizing empirical

data, not as objective structure of reality and discourse

[12]Concerning Confucianism, B. Schwartz is

right when he says, “To Confucius knowledge does begin with

the empirical cumulative knowledge of masses of particulars,...

then includes the ability to link these particulars first to

one’s own experiences and ultimately with the underlying

unity that binds this thought together.” Benjamin Schwartz, The

World of Thought in Ancient China, p.89.

[13]Lun Yu, XV 3.(tr. Waley)

[14]Ibid., II 15

[15]Lao Tzu, Chapter 1

[16] F.Wallner has makde the distinction

between Wircklichkeit and Realität, thus proposing a

theory of two types of reality. But I think this theory of two

types of reality is not enough to tackle with the problem of

Life-world. That’s why I have enlarged it into a theory of

three connected levels of reality: Reality Itself, Constructed

Reality and Life-world. Cf. See Fritz Wallner, Acht

Vorlesungen uber den Konstruktiven Realismus,(Vienna:Vienna

University Press, 1992); Vincent Shen, Confucianism, Taoism

and Constructive Realism, (Vienna, Vienna University Press,

1994)

[17]Lao Tzu, Tao Teh Ching, ch.1

[18]Vincent Shen, Annäerung an das

taoistiche Verstädnis von Wissenschatt. Die Epistemologie des

Lao Tses und Tschuang Tses, in F. Wallner, J. Schimmer

ed., Grenzziehungen zum Konstruktiven Realismus, (Wien:

WUV-Univ.Verl.,1993), S188ff.

[19]F.Wallner has initiated in recent year the

philosophical movement of Constructive Realism, as an

epistemology of interdisciplinarity, with which I myself has been

in cooperation from its beginning. I myself have introduced the

dimension of interculturality into Constructive Realism and

applied my philosophy of contrast to Constructive Realism. See

Fritz Wallner, Acht Vorlesungen uber den Konstruktiven

Realismus,(Vienna:Vienna University Press, 1992); Fritz

Wallner/Joseph Schimmer/Markus Costazza(Eds), Grenzziehungen

zum Konstruktiven Realismus,( Vienna, Vienna University

Press, 1993); Vincent Shen, Confucianism, Taoism and

Constructive Realism, (Vienna, Vienna University Press, 1994)

[20]Lao Tzu, Tao Teh Ching, ch.52

page last modified: 27-05-00 13:32:44