Rabia

Every morning I use the thumb and first two fingers of my

right hand to pleat my sari six times before tucking it in

against my waist. This is when I ready my mind for the day's

work. Each pleat is essential to me; everything in my life falls

perfectly in place between them. If I am in a hurry or let my

attention wander, the folds will be crooked and the cloth will

slip under my foot as I walk. Or maybe the knot will become a

hard lump pressing into my side. On these days I know that

things will not go well.

Obedience. Always keep your ears open for the bell above

the masala cupboard, when it rings leave whatever you are

working on and run upstairs with your tray. When you run, do

not slap your feet heavily on the floor like the buffalo that you

are, step quietly. After cleaning my room, spray the air

freshner. When you buy your paan, make sure there is no jorda

inside, I don�t care how much you like it, and don�t ask me why,

these things are not told to you for a reason. So what if you

have cleaned the gudam, do it again, sweep it properly, in your

hands even the newest jharu lets dirt through. Don�t argue with

Selim Bhai if he wants his tea earlier today, do it for him, and

don�t you dare screw your face into the ugliness that I have

been trying to make you hide, but you never listen.

The first is most important. The rest have to be the

same in broadness so that they all look like one. And if the

first is too thick, then there will not be a respectable amount

of cloth left at the end to throw over my shoulder and cover me.

Humility. When you play with Apa, do what she wants.

Remember that you live in their house, and that you eat what

they let you eat. Don�t ever let me see you forgetting yourself

and the filth you come from. If it were not for Shahib's

generosity, you would be one of those whores on the street

corner; fighting with the rickshawallahs. But that's probably

what you want to be, huh? Never look a man in the eye, Allah

made us weaker so that we listen for our own good. Did I hear

that you raised your voice at Jalal Bhai? That you raised your

voice at the man who took care of you when you were small. And

you ask why your father left! We will never find you a husband,

not with all the proud airs you give yourself, disagreeable

woman that you are.

The second comes easier. After folding, I pinch it

tightly against the first, using my thumb and third finger. With

my left hand I pull a fresh stretch from the cloth lying coiled

on the floor, waiting to twist itself around me.

Assiduity. There is very little soap today, use the

softer rock to wash the clothes, but make sure you get all the

marks out. Are you listening for the bell? You must improve

your firni, what kind of girl cannot make a decent firni? And

Jalal tells me they have eaten the same bhaji three times this

week. Learn new ones. The cat has left shit all over the

entrance, run now before Shahib sees it, but clean the floor the

right way, squat on your heels; don't wet your sari, you're

lucky they gave you one at all. Apa wants nashta, make sure you

take her the hot chutney. You cannot take your day off this

month, they are having an Iftar party on Friday. Always check

the spoons before giving them to guests.

By the third pleat, my green petticoat disappears. Only

cheap women wear fabric thin enough to let it show.

Beauty. Comb your hair every morning, use only one

handful of your Eid oil, you know Memshahib hates the smell.

Make your kajol line very thin, you are not Sri Devi, the only

men that will pay attention to you are like Hakim from next

door, with two wives in every district. Take a bath before lunch

so that the others don't have to smell your stink. Use mendhi

only for special days as Eid and at weddings. Eat more rice,

what husband will want your skinny bones? Remember to use neem

twigs to clean your teeth. Stay out of the afternoon sun, if

you sit chatting with Alam in the garden, you will become ugly

as a dog.

The fourth I have to do carefully. If I have been doing

things right, there should be a hole in front of my right leg,

and I must make certain it will be hidden under the next fold.

Hospitality. When Rohima Aunty's children come with

their ayah, make sure she gets tea and nashta before leaving.

It does not look good to let her leave on an empty stomach.

They talk about these things afterwards. Also if you see that a

driver has been waiting for more than an hour, get him some

too. But when you go to him, remember to cover your head and do

not look him in the face if you can avoid it, you being such a

hussy. If Apa wants paan and there is none in the kitchen, give

her yours, the poor girl has to listen to Memshahib screaming

all day as it is. When home on your day off, if anybody visits,

be the first one to seat them and cook for them; show everybody

that you're not like your lazy cousin Sokena.

After the fifth, without fail I worry that I have been

too generous with the pleats and that there will not be enough at

the end. Even though I checked with the fourth.

Modesty. Always cover your head with your sari. So

what if Alam Bhai is like a father, a harlot like you is always

scheming. Dry your petticoat and undergarments inside, it will

take longer but we don't want to embarrass others with your

filth. Sit with your legs tucked underneath; do not use the

wooden stool if there are any men around, use a clean piece of

the floor. Learn to speak quieter - nobody wants to hear a

woman's whine. Speak little to anyone that is not close family;

never tell too much, only what you must. If there is new darwan

in the house, make sure to tie your hair before leaving your

room. This is the right way to cut cloth for a blouse. This is

how you cover your head when you hear the Azan; always remember

or else your son will not grow up a good Muslim.

With the last fold, I am ready to start the day. I throw

the end over my left shoulder and tuck it in at the front.

Hopefully it will be fine till my afternoon bath, after which I

will start all over again with my other sari.

*******************

Things have changed after Apa left for America. Because

I do not work for her any more, they find other ways to keep me

busy. I am mostly needed in the kitchen now. Sometimes Amma

wants help with the cooking; or with washing glasses and plates;

the steel dishes; tea cups. It is also my job to arrange the big

table for meals; Hannan Bhai seldom helps any more. In the late

morning, after the bazaar has been cut and cleaned, I cook our

lunch on the outside oven. Amma and Hannan Bhai do not join us :

they wait till Memshahib has finished her meal. Once she is

resting, they finish the leftover food. I join them if I have

not eaten already. The whole time I have to keep my ears open

for the bell above the achar cupboard. It is how they call me.

All day, I load and carry up the trolley if they want anything

upstairs. I am expected to stay clean enough to come in front of

guests, though I do not greet them at the front door. That is

Hannan Bhai's job.

In the heat of the afternoon, Memshahib dims her room

lights and turns down the music. This is our free time; it is

safe to bathe or nap. On Thursdays when the natoks start early,

we gather outside the kitchen at four o'clock. There is an old

black and white television for us, and if the broken antenna

catches anything, we watch it. Shahib usually comes home from

office around six o'clock and expects nashta to be ready. I have

the heavy wooden trolley clean and the tea boiling much before then.

When Apa returns home every year, things get even

busier. The house will be full of guests, I run up and down with

hot puris or chanachur; run to warn young couples that someone is

coming downstairs or that their car has arrived. There is much

more to clean with all the dirty shoes going in and out all day,

but Amma does not understand this, she only screams. And Apa

always has new clothes that I have to wash because she does not

trust any one else and then they have to be ironed exactly the

way she likes.

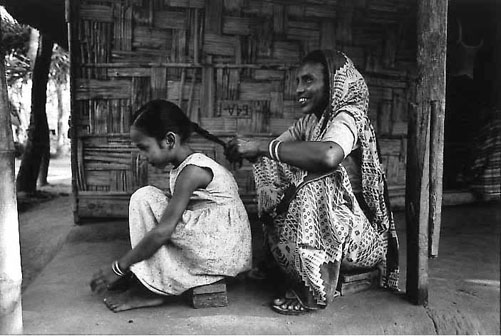

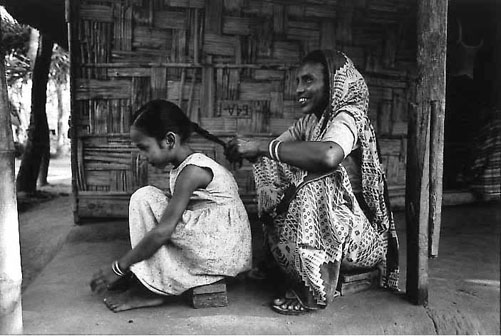

But I like it when Apa is home again. Sometimes she

asks me to sit and talk. Apa has changed since leaving, she is

quieter. I lay my tray carefully on the carpet and draw my knees

to my chin. This reminds me of when we were still children. She

would come downstairs to the quarters to visit me. We sat just

like this, she would carefully perch herself on the wooden

folding chair left from an Eid milad, while I squatted on the

ground at her feet. Often she came with a new toy she wanted to

share. And when they got Sumu we would play with him together.

Selim Bhai would leave his work to come watch us. We were

usually allowed to play for an hour or so before one of us had to

go somewhere. Sometimes Amma would come and tell me to comb oil

into my hair when I already had, or wash clothes I knew she had

wanted me to take care of the next day.

I am also quieter with Apa now. As we grew older, we had

found less and less time to spend together. So I just sit and

rock myself, and smile when Apa talks. Sometimes I ask

questions, like how did she manage on her own in America? Who

cooked for her, soaked her kameez and scrubbed it clean? Who

swept the floor and washed the dirty plates? I almost giggled

out aloud thinking of Apa doing those things for herself. But

she told me that machines took care of all the work. Machines

like the ones we would see in Hindi movie advertisements. Oh, it

would be so good if Shahib bought some of them home from his next

business trip abroad. Then they would never have to complain of

my washing or cleaning.

One afternoon I found it very difficult to stay with Apa.

This was after her second year abroad. I had peeled and taken

her some langra mangoes that Selim had found in the bazaar. We

all knew how she loved them; and these were particularly

delicious specimens - I had nibbled the juicy skin bare before

throwing it away. Apa asked me to stay for a bit. Amma was

resting in the quarter now that Memshahib was sleeping, so I had

some free time to myself.

But Apa just sat there, not even looking at me for

several minutes. Something must have upset her for I noticed

that she had twisted her dopatta into horrible knots.

Suddenly, "Why do you call me Apa?"

"'Apa'? Why?" I replied; very confused. I called her

Apa because I always have. I don't know. Because it's right.

What else would I call her? The word was the only one that fit.

"Why are you asking me this Apa? I don't understand."

"I'm asking you because you're my age, I'm not older than

you. Apa means that I'm older."

But it wasn't about being older or younger. It was about

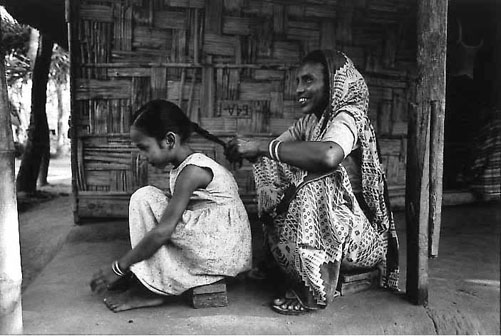

who we were. For me it was about respect and fear. For her, it

was to expect that; to know that I would have to straighten the

dopatta right now if she wanted me to; get more mangoes if she

said so. From the beginning it was the way that we had been

fixed in our positions. A permanent reminder that we were very

different, that we could never be too comfortable with each

other. There was no comfort between us; nothing I could take for

granted, even if Apa wanted me to sit and talk to her. So I just

sat there, not knowing what to say.

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]