Mother took me behind the railway tracks, where rough men mill about

tea stalls and wooden shanties. Her stern grip warned that this was to

be a quiet walk. After covering a dark and stony distance we stopped outside

a hut with a new, corrugated-tin roof. Ruffians looked us over.

I was restless, but Amma stilled me with a sharp jerk. She spoke to them,

asking for a Baba Mia. We were told to wait. A few beetle-spitting minutes later, a man came out of the hut. He

had a stillness about him that made him difficult to see. He was Baba Mia,

and wore a clean and freshly ironed shirt. He lead us inside.

I sensed two things after we entered- a rotten smell and a strange humming.

And then I saw the drums. There were stacks of them, some new,

others rusted, but all tied in place with jute cords. Neatly arranged, each

was covered with markings of white chalk. I realized that the stench and

sounds were coming from these small drums. The smell was that of decayed flesh,

like of spoiled meat that even lemon did not hide. But stronger.

And the humming? It was as deep as earth sounds and listening closer,

I could hear an undercurrent of scraping and knocking, moving and crying-

as if there were a thousand echoes in that hum.

Baba Mia walked over to a drum that had been pulled apart from the

rest and pointed to it, "Check the markings. It is Munmun."

Amma looked it over and said "Yes, it is mine indeed." She traced

shaking fingers over the chalk scribble. It was obvious that these fingers had

done a good job of memorizing the figures; it was also obvious that my

mother was filled with a very, thick dread.

"To wait any longer might kill her." he said quietly. Amma nodded. The

man then lifted the lid off the drum and reached inside with one

hand. And he pulled out my three year old sister.

Leaning on a rusty telephone pole, I remember all this. I am

not sure why the memories came to me today, it is not a day for idle

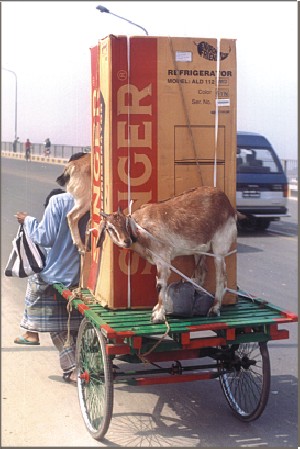

thoughts. It is raining this evening. Munmun is cranky. She sits in her cart and

makes faces. With this attitude she is not going to make us any money

and when I tell her so, she looks away. I don't know what to do. I hate the

rain.

We should move as no one will visit the market in this downpour. The guard

has also walked by twice, slapping his cane against his boots threateningly.

His uniform is scrupulous and neatly pressed despite the weather.

We should not be here on his third round. I tell Munmun that maybe someone

will let us use their porch in the adjoining street. Maybe there will even

be something to eat. But she only grunts and I ignore her. Tucking

her wet clothes around her, I drape her with our piece of translucent blue

plastic. And I start to push. It is difficult when the streets are wet.

Mud cakes the tin-can wheels, making the wooden cart swerve. My bare

feet are unsure of how to step and Munmun flops uncontrollably, her

arms poking branch-like.

When we reach the other street, the houses look poorer than I

remembered them to be. We begged here months ago. In the fading light I

scan the length of the potholed road and find it almost empty, except for

two dogs in a pile of garbage. I stone them away to check if there is

anything good, but they have done a thorough job. I push Munmun to a

thatched door and knock. Almost immediately, as if expecting us, it is

opened by a bare-chested man who tucks in his lungi and raises a leg to

kick at the cart. I pull away my outstretched hand and wrench Munmun back.

"Thieving bastards, wait, let me get my stick." He feigns a rush, but we

are safe in the rain. We try other houses, but are mostly yelled at and

even have trash thrown at us. One enraged man hurls his dinner chapati at

us. We share it, laughing while we chew the warm bread. And finally we

get lucky when a dull eyed woman espies us and opens her door. She let us

in without a word.

Her house is bare, but cool and dry of moisture. I feel myself steaming

like a fresh rice cake.

"Poor children. Sit down boy. It is bad outside." I sit on the earthen

floor, folding my knees to rest my chin.

"You are very wet.� I nod. She then asks Munmun, "Are you his sister?"

I answer the question "She is. She can't talk. She can understand

though. Her name is Munmun."

"Munmun", the woman repeats. "Poor Munmun. Look at poor Munmun." She

removes the plastic which looks almost pretty in this dark house, and the

layers of draped cloth to understand my sister. She eyes the knotted stubs

of what were legs and mangled bones for arms; then with a rag pats the

white scars dry. She notices the little bag with feathers that Munmun

collects to stitch into a pillow one day. I had told her once that she

cannot sew, but Munmun is stubborn.

The woman clears knots in Munmun�s hair and uses a ripped saree to tie it

back neatly. And calls deep in her throat "What have they done to her?"

I know why this woman is so soft. No children live in this house. Women

like her otfen help us, but they are mixed blessings. For when it is time

to leave, Munmun will sulk for days. Because we always have to leave.

Because she has never had a mother.

The woman uncovers little tin bowls, and gives us a ball of rice and

divides an egg. I sense that this is a luxury and more than she can

afford. Later as she takes our clothes and spreads them to dry, Munmun

falls asleep but I keep watch. I know the woman will want to talk.

"Poor Munmun, what have they done to her? Why? How terribly...How could a

little thing like her survive it?" She was not really speaking to me

though. On her haunches, she was rocking her thoughts out, somewhat like

that man with the stick. Before, I used to wonder why the sight of Munmun

and I anger people so much. I think I know why now. We disgust them, and

sicken them, because what if, by some twist of fate, we had been their own

children.

My head is light with sleep, so I talk a little. "I never knew why mother

took her, when they made her like this. I was small then. We have been on

the streets for five years now. I don't know how we would beg if they

hadn't changed her. But I would never have let them take her if I had

known. But I was small then."

"Do you have anybody? In your village home?" she insists, but her squinted

eyes tell me she is still making words, not sense. Maybe she is thinking

of green mangoes from her own childhood days- she must be from outside the

city.

I shake my head. "I keep thinking that maybe we can find somewhere to

stay, where I can work. There are construction sites, I can break bricks.

But what about Munmun, she doesn't like being alne for that long?"

Later she tells me that we can pass the night there. I turn to sleep. At

some point, I think I hear the woman crying. But I sleep.

As the first streaks of light crack through the brick wall, she shakes my

shoulder. Her husband will return from the factory and we should leave.

Munmun is already awake. She has that blank look on her face. Together

the woman and I cover her with the plastic. Without a word I push the cart

out.

Outside there is no dust after the long night's rain. My wood grip is warm

and I push energetically. The street taps out the sounds of five in the

morning. And as we track the sun come up, from somewhere between green

leaves and a brick building, I think it will be a bright day.

[email protected]

[email protected]