| Antarctica - Nuggies On Ice |

| [ Home > Other Pages > Big Storm ] |

| This story may be a little long by the time I get to the end of it, but I guess there is a lot to talk about following the big storm we had down here on 16th June, 2004. We think we had the biggest storm since records began at Scott Base, but we can never prove it. The anemometer lost a cup in the fierce winds and officially the wind speed was a smaller figure than what we know we experienced. However, we took away from here a healthy respect for the power of the wind, realising that what we put here could be removed at will by Nature. So on with the story ... It was a dark and stormy night ... |

| The BIG Storm ... |

| We knew we had a storm coming - a herbie as they are called round here. The barometer was dropping, the temperature was rising and we had snow falling. All of these were indicators that backed up the weather forecast issued by Mac Weather at McMurdo. They predicted winds of 40 - 60 knots, gusting to 85 knots. While it would be unpleasant outside in such conditions, this was about normal for a herbie. On Saturday afternoon the weather conditions started to deteriorate, but were not too severe. Two people left Scott Base in windy conditions but with reasonable visibility to go to the A-Frame. The A-Frame is a chalet-style building used by Field Training Instructors during summer and for get-away weekends during winter. Shortly after they arrived, the wind had increased to 30 - 40 knots coming from the north. This was a bit unusual for a normal herbie. The wind recorder showed that these conditions continued through the night, with gust up to 50 knots. Around 5.00am, the wind suddenly dropped from the north and swung immediately to the south. Within about 15 minutes, the wind was blowing up to 80 knots and things around here were starting to shake. In fact the accommodation buildings were shaking so much that it woke us up. One by one we went to look at one of the many weather condition instruments placed around the base. These are for noting the weather conditions outside before venturing forth. By the time I arrived at the instruments in the dining room, the wind was registering off the dial of the wind speed indicator. This meant the wind speed was greater than 90 knots, (that's about 104mph or 167kph). The wind direction was due south and the temperature was about -16 degrees Celsius. Visibility outside was next to nothing. It was dark, but blowing snow meant that floodlights about 2 metres away could just be seen. |

| Jamie, the science technician noted the high wind speed and hurriedly switched the pen recorder to its high range to record the high wind speeds. The pen recorder had been hammering against the stop for at least 10 minutes when this was done. On the high range the pen recorder immediately registered a gust of 112 knots (134mph or 208kph). The barometer had risen sharply about 10 millibars. Over the next few hours the atmospheric pressure rose or fell in rapid jumps. Passing through one of the linkways, it was noticed that the door on our waste water treatment plant had blown open. Even though the light through the open |

| door was less than 3 metres away, it could only just be seen. The door could not be left open, as the wind would destroy it and possibly the building as well. So one of the engineers and the carpenter dressed themselves up in ECW clothing and went outside to close the door. They could just be seen as they entered the doorway. The door catch was adjusted and they returned inside, covered in snow and with ice build-up all over their faces. In the composite picture above there are the following. Top left are the wind direction and wind speed indicators, along with the outside temperature gauge, shortly after the wind changed direction. Top right is the wind speed pen recorder showing the peak of 112 knots after being switched to the high (double) range. The peaks past 90 knots were all on the low range and it is unknown what the true wind speed was at that time. Bottom left is the sharp rise and fall in atmospheric pressure recorded on the barometer. Bottom right is all we could see of the open door from the linkway window. The storm continued to blow fiercely all day and showed no sign of abating. The two people at the A-Frame were not as fortunate as we were. During the night, when the wind was blowing from the north, snow started to blow in to the hut around the chimney of the diesel heater. This eventually covered everything inside the hut, including their bedding, with spindrift. After a time, the chimney started to block and the diesel heater started to backfire. Fumes started to fill the room and, when the smoke detector fire alarms went off, they were eventually forced to turn the heater off. By morning they were very cold and miserable. Luckily a small gas stove was able to be started and they could boil water for drinks and heat food. By the time the storm had turned to the south they were trying to stay warm inside their damp bedding. Radio communications between the A-Frame and Scott Base became marginal, with so much snow being blown through the air. As well as being a dense wall of snow, the snow rushing through the air generated considerable amounts of static electricity. Both of these conditions made it very difficult to hear what was being said at the A-Frame. We had two fire alarms during the day. The first one was due to snow melting above a smoke detector in the main powerhouse, dripping on to it and setting off the alarm. The second one occurred because of a frozen water pipe leading to a fire hose. The frozen water broke the pressure switch at the hose reel and set off the alarm. Throughout the day the wind continued to blow unabated. Finally, in the early evening, the wind started to ease. Radio communications stabilised and we were able to advise the people at the A-Frame that if the conditions continued to improve, we would be able to come out and bring them home that night. The vehicle they had taken out was not equipped with GPS and it was likely that it would not start anyway. The engine was very likely full of snow. About 10.00pm the wind had dropped to 20 - 30 knots and a Hagglunds vehicle was sent out to bring them back. There was still a lot of blowing snow, but the Hagglunds was able to navigate with GPS. An hour later and everybody was safely home. The storm had passed and things were going to return to normal, even though another storm was being forecast for Tuesday. |

| The BIG Clean-up ... |

| The next day we set about finding what damage had occurred. We had some idea what we were in for. As the storm started to abate on Sunday afternoon, somebody had ventured out to the hangar, (our warehouse building), to find that the main door that faced the south had been blown in. We knew we had a big clean-up job in the hangar, but had no idea just how much. The door track had been forced out of alignment by the wind and the door had come loose. Without the track to hold the door in place, the counter-weight collapsed the door so that it inverted in the doorway. The photo on the right shows the door from the outside. What you can see of the door is the inside of the bottom of the door. The top of the door is on the inside near the floor. Inside the hangar everything was covered in fine snow. The fine particles had been blown everywhere. In places items were covered in snow over 300mm deep. The second picture on the right shows Ewan, our Field Support Officer, standing amongst the white desolation that is our hangar. This gives some idea of the task that lay ahead. |

| On the left is what greeted Ewan when he entered his office in the field store, some 10 metres inside the building from the main door. The door to his office was held closed by a hydraulic door closer, but the force of the wind had ripped the closer off the doorframe and the door was blown open. The fine snow driven in by the wind had covered everything in his office/workshop to a depth of about a centimetre, with a large build-up on the floor. The electrical switchboard, like so many others round the base, had been filled with snow also. |

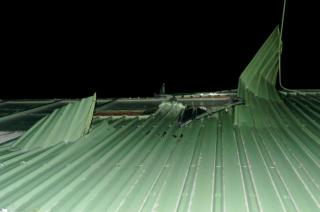

| The outside of the hangar had not escaped unscathed. Approximately a third of the roofing steel on one side of the hangar roof had been torn off by the wind. Some of the torn sheets remained on the roof at crazy angles, as can be seen in the picture on the right. However, a lot of other sheets had been thrown to the ground. They are all beyond repair and the roof has had a temporary repair made to it. Permanent repairs will have to wait until new roofing materials can be flown in on the first flights of Winfly, (in August). |

| Elsewhere around the base, huge drifts of snow had built up on the leeward side of the buildings. These alone meant days of work ahead clearing roads and exits from the base. On the left is our D6 bulldozer almost completely buried and on the right is the rear exit from Q-Hut, both drifts over 2 metres deep. |

| The engineering staff had recently spent a lot of time fitting out and placing a container for storage of LPG cylinders that would be used after our kitchen had been converted to gas working. That container was flipped on to its side and almost hit the main diesel storage tank, (below left). A short distance away another container, that is going to be used for staging fuel drums and other materials for helicopter loads during summer field deployment, was tossed end-for-end. Along the way it knocked over another small storage container and finally landed on a new frame that was designed to hold the mobile diesel tank used to transfer fuel from McMurdo bulk fuel depot to our main diesel tank, (below centre). Around the back of the base, a small container, used during the last summer for storing explosives, had been tipped on its side, (below right). |

| More damage became apparent as we checked further. Two vehicles on our hitching rail had their windows shattered, (right). Whether it was wind pressure or flying debris, we have no idea. Both vehicles slowly filled with snow blown in by the wind. One vehicle was sitting cold as it was out of service, but the other vehicle had a cab heater working. The heater worked for a little time, melting the snow and forming dirty icicles, but in the end gave up. A lot of effort will be need to thaw these vehicles out, but they will not be able to be used again this winter. New windows will have to be flown in for the new season. |

| Inside the base there were problems also. Fine snow blows through every little crack or hole. The picture on the left shows the snowdrift that built up under our auxiliary powerhouse when large quantities of snow were blown through a hole that developed inside a ventilation shaft. The picture on the right is typical of the small build-ups that occur around window frames and doors that are not sealed tightly. This small drift is what entered A-Hut, the first building at Scott Base and which is the Trans-Antarctic Expedition museum. |

| The A-Frame problems would have to wait, since more pressing matters needed to be dealt with at Scott Base. The pictures on the right were taken by one of the people trapped there during the storm. The top picture is the snowdrift that built up on top of the diesel heater after it was turned off. The sofa on the left of the picture gives an idea how deep the snowdrift is. The second picture is the vehicle that had to be abandoned. The Argo lost its rear cabin during the storm. At the moment we have no idea where it went. Once again, this vehicle may have to wait until the new season before it can be used again. It has since been recovered from the A-Frame. On top of all the obvious major damage there is a lot of minor damage. Debris blew everywhere. Items stored outside were blown away. The reality of it all is that we will be picking up dispersed items for a long time yet to come. When the snow disappears in summer will be the time to pick up what remaining items can be found. For the moment though there are still weeks of work ahead cleaning up. |

| During all this it was good to see that morale is still high, even though people are very tired. There is a sort of black humour involved in the sorting through items that are found, both here and at McMurdo. Daily e-mails and phone calls ask if either side has lost certain things, because they have been found lying about. A lot of things are being found that have probably been forgotten over the years and the storm revealed them again. |

| McMurdo suffered similar types of damage to Scott Base. Of course the size of that station means that the size of the clean up is correspondingly bigger. They also lost sheet metal off buildings, had doors blown in and buildings fill with snow. They also had the problem of burst water pipes that flooded buildings. A major morale problem for them is that they lost their television signal from the satellite station on Black Island. While movies and similar programmes have been broadcast from the McMurdo television station, they have been without incoming news broadcasts for the last week. The pictures on the left show what could have been a major disaster with the potential for environmental damage and possible loss of life. They have been using an old bulk fuel storage tank for storage of, amongst other things, truck tyres. A hole had been cut in the side and a roller door fitted. During the storm this door blew in and the air pressure was so great that the roof of the tank broke all welds and took off. Luckily the tank lid fell into a disused pit and missed a huge bulk diesel tank and did not carry on into the town. The picture above shows where the roof used to be and the picture below shows the crumpled steel roof about 50 metres away from the tank. |

| As mentioned earlier, the people at McMurdo lost their satellite television link to the United States. It wasn't until about a week later that technicians from the station were able to get across to Black Island, where they have their satellite receiver station. When they got there, the reason for the loss of signal was very apparent. On the right is all that was left of the equipment. The radome that used to be around the dish has disappeared to parts unknown and the dish itself was bent and buckled. This meant a few more weeks of viewing pre-recorded programmes and getting news from the Internet. |

| When we compared notes with our friends at McMurdo, we got a further surprise. The wind speed records from their NASA satellite tracking dome showed that, for the eight hours of the height of the storm, the wind had maintained peaks of 110 knots (200 kilometres per hour) and averaged more than 80 knots (144 kilometres per hour). The peak wind gust recorded was an amazing 139 knots (257 kilometres per hour). The NASA tracking station is only 4 kilometres from Scott Base so, while those readings were recorded at McMurdo, they indicated conditions very similar to what we experienced. |