10 May 2007

Interests & Distractions

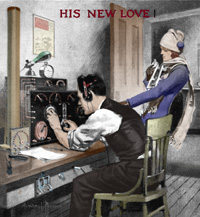

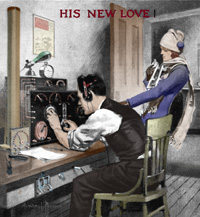

"There's a Radio Station in There!"

My

fascination began over 55 years ago. I was about two years old. My father

put the carbon microphone that was part of our Sears Silvertone family

radio console in front of my face and asked me to say something. Being

much more contextual then than I am these days, I said "There's a radio

station in there." I knew it then as truth. There always was.

My

fascination began over 55 years ago. I was about two years old. My father

put the carbon microphone that was part of our Sears Silvertone family

radio console in front of my face and asked me to say something. Being

much more contextual then than I am these days, I said "There's a radio

station in there." I knew it then as truth. There always was.

You see, Dad's voice came out of that huge veneer box every day. It was to my young mind as if my father magically became a miniature announcer in a miniature radio station that was part of the innards of that elegant wooden cabinet. Of course, as I grew older, I came to understand just how all that magic worked.

When Sputnik began circling my world on that October day in 1957, I heard

the news on an old Zenith five-tuber that my parents had moved from the

kitchen to my bedroom. Before long, some of my friends had little crystal

sets -- new-fangled devices then -- shaped like miniature red rocket ships.

I never got one. Instead, Mom got me a copy of The Boy's First Book

of Radio. From that book and my father's stories about his youthful

addiction to radio, I learned how those crystal sets worked. I built every

circuit in the book and then tacked on amplifiers and speakers and other

circuits, every one of them constructed on a collection of one inch pine

blanks with screws for tie points between the parts.

When Sputnik began circling my world on that October day in 1957, I heard

the news on an old Zenith five-tuber that my parents had moved from the

kitchen to my bedroom. Before long, some of my friends had little crystal

sets -- new-fangled devices then -- shaped like miniature red rocket ships.

I never got one. Instead, Mom got me a copy of The Boy's First Book

of Radio. From that book and my father's stories about his youthful

addiction to radio, I learned how those crystal sets worked. I built every

circuit in the book and then tacked on amplifiers and speakers and other

circuits, every one of them constructed on a collection of one inch pine

blanks with screws for tie points between the parts.

Around 1959, Dad took me downtown to Custom Electronics, the local radio store, and plunked down $71.75 for a Hallicrafters S38E short wave receiver. The first station that I tuned in was Radio Havana, Cuba. Then I heard Deutsche Welle, the "Voice of Germany." As I listened around I found the Voice of America Jazz Hour and learned about Thelonius Monk and Art Blakey. I discovered jazz music, the melodies of the Spanish language, jibara & musica campesina, the politics of the left and the religion of the right. I tried learning Morse code in hopes of getting a ham radio license. I wrote reception reports. I collected QSL cards.

In the end, I came to speak Spanish with a Cuban accent, played tenor and

alto sax with local jazz groups on "the black side of town," got two free

copies of Chairman Mao's Thought and, by the beginning of 1966, forgot

all about that magical radio station that hid inside the box, all its politics

and music and Mexican beer commercials replaced by hippie hedonism.

In the end, I came to speak Spanish with a Cuban accent, played tenor and

alto sax with local jazz groups on "the black side of town," got two free

copies of Chairman Mao's Thought and, by the beginning of 1966, forgot

all about that magical radio station that hid inside the box, all its politics

and music and Mexican beer commercials replaced by hippie hedonism.

By 1968 I was in the US Navy, sent off to Norfolk, Virginia, to learn how radio teletype worked in the defense of all the things that the short wave radio had taught me . . . or made me question.

In Puerto Rico, I was surrounded by communications gear that made the old

Hallicrafters look like a crystal set. I got interested in amateur radio

again. I got my first ham radio licence and built a Heathkit receiver and

transmitter. I got on the air. I talked to people in Sweden, Russia, France

and England. By the time I got orders sending me to the USS Saratoga, I

was hooked, deepfried & wrapped in radio.

In Puerto Rico, I was surrounded by communications gear that made the old

Hallicrafters look like a crystal set. I got interested in amateur radio

again. I got my first ham radio licence and built a Heathkit receiver and

transmitter. I got on the air. I talked to people in Sweden, Russia, France

and England. By the time I got orders sending me to the USS Saratoga, I

was hooked, deepfried & wrapped in radio.

When I got out of the Navy in 1972, I eventually ended up on the production line of the R.L. Drake Company, testing, repairing and turning out 20 high-performance amateur radio transmitters and receivers a day. That led me to the job I have now, working in the educational media department of the same university from which I went to join the navy.

There's a radio station in there . . . somewhere.

Now I my radio friends range from a bunch of lunatics who build and operate radios that run less power than the lights on the family car to your garden variety antenna-designing acrophobic crazies. Tiny radios in mint tins have replaced those red space ship crystal sets. Other more complicated and up-to-date radiosmake the magic all that much more interesting.

If you want to know more about my collection of radio toys, you can go

to my "real" amateur radio page by clicking on the sparks . . .

If you want to know more about my collection of radio toys, you can go

to my "real" amateur radio page by clicking on the sparks . . .

The Tagalong Press

One

of my earliest auditory memories is the sound of my father's 1890s-vintage

printing press clattering away in a room of the house in Amarillo, Texas,

where I spent the first years of my life. That sound is today part of my

life in ways that I might never have imagined. It doesn't help much that,

at some point in my early years, Dad dipped my tiny fingers into a can

of black letterpress ink and thus doomed me to a life that has always been

near printing.

One

of my earliest auditory memories is the sound of my father's 1890s-vintage

printing press clattering away in a room of the house in Amarillo, Texas,

where I spent the first years of my life. That sound is today part of my

life in ways that I might never have imagined. It doesn't help much that,

at some point in my early years, Dad dipped my tiny fingers into a can

of black letterpress ink and thus doomed me to a life that has always been

near printing.

Over the course of the past 52 years, I've been drawn back often to the sound of a press thumping away somewhere nearby. When I first got out of the Navy, I worked for a while in the composing room of the same weekly

newspaper where Dad was then a reporter.

the Navy, I worked for a while in the composing room of the same weekly

newspaper where Dad was then a reporter.

Today my father's printery sits in the garage, having pushed out the family cars and filled the space with nearly four tons of cast iron printing machines and another two tons of hand-set type and other accouterments of a by-gone era in graphic arts trade.

Today, I print for fun, if such a concept can be understood. Hand set type takes a certain patience. Working with large forms of heavy type metal requires a careful eye, leverage and brute strength. But what I see coming off the presses gives me a sense of satisfaction that is difficult to explain.

Much of what you see here on these pages reflects my own sense of shape and type and form. I choose my type faces on the screen as carefully as I do the metal in the case. Mixing ink is, in this digital medium, a process of trust and luck. But it all comes out the same: shapes on the page that you can read and understand as reflections of my thoughts.

What Gutenberg once brought to the world is, of course, changing daily

in this computerized age. But the changes that come from expanding literacy

demand a certain amount of talent.

the page that you can read and understand as reflections of my thoughts.

What Gutenberg once brought to the world is, of course, changing daily

in this computerized age. But the changes that come from expanding literacy

demand a certain amount of talent.

I like to think

that I have that talent, but I have it only because I was taught well,

by a man who learned it the hard way, one letter at a time, one sheet at

a time, one foot balanced on the floor and the other balanced on the treadle

of a trusty cast iron press.

I like to think

that I have that talent, but I have it only because I was taught well,

by a man who learned it the hard way, one letter at a time, one sheet at

a time, one foot balanced on the floor and the other balanced on the treadle

of a trusty cast iron press.

What else you see here comes from my presses. Time spent in silliness, to be sure. Toys much larger than anything my childhood could have imagined. And this connection of sound and light that brings it to you. Enjoy what's left of your literacy in this age of electronic text & visual cuing. After all, it's reading . . . It's the latest rage.

Language & Literacy: The Mandatory Sentence

It should come as no surprise that all of these

hobbies eventually lead back to human communication, language, writing

& reading, listening & speaking. That they do is part of the personal

metaphor of my life, a collection of keyboards, composing sticks, mathematical

formula for the diversity of solving the essential problem of who we are

& how we continue to be even after our voices have been taken into

the overall silence of infinity.

It should come as no surprise that all of these

hobbies eventually lead back to human communication, language, writing

& reading, listening & speaking. That they do is part of the personal

metaphor of my life, a collection of keyboards, composing sticks, mathematical

formula for the diversity of solving the essential problem of who we are

& how we continue to be even after our voices have been taken into

the overall silence of infinity.

Out of all the words that are spoken daily by me and others around the world, each voice has a particular story behind it. Each voice adds to the unending continued conversation that is part of our common humanity. Each voice makes us who we are, determines who we appear to be and tells every person on this planet the story of the infinite struggle that all those voices, all those words, all those languages represent.

We are more than the Whorfian hypothesis. We are more than the Darwinian process. We are more than any deconstruction, any collection of academic sense of destiny. We are the grand gibberers, the archetypal mumblers, the seamless grumblers, complainers, the stumbling drunken word-droolers whose history goes back to some distant half-life of our own recognition.

We talk. We listen. And sometimes we do neither, despite our sense of having done something important with the space between our ears and the vocalizations of our waggling tongues.

So I write stories. You have been reading one.

My

fascination began over 55 years ago. I was about two years old. My father

put the carbon microphone that was part of our Sears Silvertone family

radio console in front of my face and asked me to say something. Being

much more contextual then than I am these days, I said "There's a radio

station in there." I knew it then as truth. There always was.

My

fascination began over 55 years ago. I was about two years old. My father

put the carbon microphone that was part of our Sears Silvertone family

radio console in front of my face and asked me to say something. Being

much more contextual then than I am these days, I said "There's a radio

station in there." I knew it then as truth. There always was.

You see, Dad's voice came out of that huge veneer box every day. It was to my young mind as if my father magically became a miniature announcer in a miniature radio station that was part of the innards of that elegant wooden cabinet. Of course, as I grew older, I came to understand just how all that magic worked.

When Sputnik began circling my world on that October day in 1957, I heard

the news on an old Zenith five-tuber that my parents had moved from the

kitchen to my bedroom. Before long, some of my friends had little crystal

sets -- new-fangled devices then -- shaped like miniature red rocket ships.

I never got one. Instead, Mom got me a copy of The Boy's First Book

of Radio. From that book and my father's stories about his youthful

addiction to radio, I learned how those crystal sets worked. I built every

circuit in the book and then tacked on amplifiers and speakers and other

circuits, every one of them constructed on a collection of one inch pine

blanks with screws for tie points between the parts.

When Sputnik began circling my world on that October day in 1957, I heard

the news on an old Zenith five-tuber that my parents had moved from the

kitchen to my bedroom. Before long, some of my friends had little crystal

sets -- new-fangled devices then -- shaped like miniature red rocket ships.

I never got one. Instead, Mom got me a copy of The Boy's First Book

of Radio. From that book and my father's stories about his youthful

addiction to radio, I learned how those crystal sets worked. I built every

circuit in the book and then tacked on amplifiers and speakers and other

circuits, every one of them constructed on a collection of one inch pine

blanks with screws for tie points between the parts.

Around 1959, Dad took me downtown to Custom Electronics, the local radio store, and plunked down $71.75 for a Hallicrafters S38E short wave receiver. The first station that I tuned in was Radio Havana, Cuba. Then I heard Deutsche Welle, the "Voice of Germany." As I listened around I found the Voice of America Jazz Hour and learned about Thelonius Monk and Art Blakey. I discovered jazz music, the melodies of the Spanish language, jibara & musica campesina, the politics of the left and the religion of the right. I tried learning Morse code in hopes of getting a ham radio license. I wrote reception reports. I collected QSL cards.

In the end, I came to speak Spanish with a Cuban accent, played tenor and

alto sax with local jazz groups on "the black side of town," got two free

copies of Chairman Mao's Thought and, by the beginning of 1966, forgot

all about that magical radio station that hid inside the box, all its politics

and music and Mexican beer commercials replaced by hippie hedonism.

In the end, I came to speak Spanish with a Cuban accent, played tenor and

alto sax with local jazz groups on "the black side of town," got two free

copies of Chairman Mao's Thought and, by the beginning of 1966, forgot

all about that magical radio station that hid inside the box, all its politics

and music and Mexican beer commercials replaced by hippie hedonism.

By 1968 I was in the US Navy, sent off to Norfolk, Virginia, to learn how radio teletype worked in the defense of all the things that the short wave radio had taught me . . . or made me question.

In Puerto Rico, I was surrounded by communications gear that made the old

Hallicrafters look like a crystal set. I got interested in amateur radio

again. I got my first ham radio licence and built a Heathkit receiver and

transmitter. I got on the air. I talked to people in Sweden, Russia, France

and England. By the time I got orders sending me to the USS Saratoga, I

was hooked, deepfried & wrapped in radio.

In Puerto Rico, I was surrounded by communications gear that made the old

Hallicrafters look like a crystal set. I got interested in amateur radio

again. I got my first ham radio licence and built a Heathkit receiver and

transmitter. I got on the air. I talked to people in Sweden, Russia, France

and England. By the time I got orders sending me to the USS Saratoga, I

was hooked, deepfried & wrapped in radio.

When I got out of the Navy in 1972, I eventually ended up on the production line of the R.L. Drake Company, testing, repairing and turning out 20 high-performance amateur radio transmitters and receivers a day. That led me to the job I have now, working in the educational media department of the same university from which I went to join the navy.

There's a radio station in there . . . somewhere.

Now I my radio friends range from a bunch of lunatics who build and operate radios that run less power than the lights on the family car to your garden variety antenna-designing acrophobic crazies. Tiny radios in mint tins have replaced those red space ship crystal sets. Other more complicated and up-to-date radiosmake the magic all that much more interesting.

The Tagalong Press

One

of my earliest auditory memories is the sound of my father's 1890s-vintage

printing press clattering away in a room of the house in Amarillo, Texas,

where I spent the first years of my life. That sound is today part of my

life in ways that I might never have imagined. It doesn't help much that,

at some point in my early years, Dad dipped my tiny fingers into a can

of black letterpress ink and thus doomed me to a life that has always been

near printing.

One

of my earliest auditory memories is the sound of my father's 1890s-vintage

printing press clattering away in a room of the house in Amarillo, Texas,

where I spent the first years of my life. That sound is today part of my

life in ways that I might never have imagined. It doesn't help much that,

at some point in my early years, Dad dipped my tiny fingers into a can

of black letterpress ink and thus doomed me to a life that has always been

near printing.

Over the course of the past 52 years, I've been drawn back often to the sound of a press thumping away somewhere nearby. When I first got out of

the Navy, I worked for a while in the composing room of the same weekly

newspaper where Dad was then a reporter.

the Navy, I worked for a while in the composing room of the same weekly

newspaper where Dad was then a reporter.

Today my father's printery sits in the garage, having pushed out the family cars and filled the space with nearly four tons of cast iron printing machines and another two tons of hand-set type and other accouterments of a by-gone era in graphic arts trade.

Today, I print for fun, if such a concept can be understood. Hand set type takes a certain patience. Working with large forms of heavy type metal requires a careful eye, leverage and brute strength. But what I see coming off the presses gives me a sense of satisfaction that is difficult to explain.

Much of what you see here on these pages reflects my own sense of shape and type and form. I choose my type faces on the screen as carefully as I do the metal in the case. Mixing ink is, in this digital medium, a process of trust and luck. But it all comes out the same: shapes on

the page that you can read and understand as reflections of my thoughts.

What Gutenberg once brought to the world is, of course, changing daily

in this computerized age. But the changes that come from expanding literacy

demand a certain amount of talent.

the page that you can read and understand as reflections of my thoughts.

What Gutenberg once brought to the world is, of course, changing daily

in this computerized age. But the changes that come from expanding literacy

demand a certain amount of talent.

I like to think

that I have that talent, but I have it only because I was taught well,

by a man who learned it the hard way, one letter at a time, one sheet at

a time, one foot balanced on the floor and the other balanced on the treadle

of a trusty cast iron press.

I like to think

that I have that talent, but I have it only because I was taught well,

by a man who learned it the hard way, one letter at a time, one sheet at

a time, one foot balanced on the floor and the other balanced on the treadle

of a trusty cast iron press.

What else you see here comes from my presses. Time spent in silliness, to be sure. Toys much larger than anything my childhood could have imagined. And this connection of sound and light that brings it to you. Enjoy what's left of your literacy in this age of electronic text & visual cuing. After all, it's reading . . . It's the latest rage.

Language & Literacy: The Mandatory Sentence

It should come as no surprise that all of these

hobbies eventually lead back to human communication, language, writing

& reading, listening & speaking. That they do is part of the personal

metaphor of my life, a collection of keyboards, composing sticks, mathematical

formula for the diversity of solving the essential problem of who we are

& how we continue to be even after our voices have been taken into

the overall silence of infinity.

It should come as no surprise that all of these

hobbies eventually lead back to human communication, language, writing

& reading, listening & speaking. That they do is part of the personal

metaphor of my life, a collection of keyboards, composing sticks, mathematical

formula for the diversity of solving the essential problem of who we are

& how we continue to be even after our voices have been taken into

the overall silence of infinity.

Out of all the words that are spoken daily by me and others around the world, each voice has a particular story behind it. Each voice adds to the unending continued conversation that is part of our common humanity. Each voice makes us who we are, determines who we appear to be and tells every person on this planet the story of the infinite struggle that all those voices, all those words, all those languages represent.

We are more than the Whorfian hypothesis. We are more than the Darwinian process. We are more than any deconstruction, any collection of academic sense of destiny. We are the grand gibberers, the archetypal mumblers, the seamless grumblers, complainers, the stumbling drunken word-droolers whose history goes back to some distant half-life of our own recognition.

We talk. We listen. And sometimes we do neither, despite our sense of having done something important with the space between our ears and the vocalizations of our waggling tongues.

So I write stories. You have been reading one.