Network for Environmentally- & Socially-Sustainable Tourism (Thailand) |

Mangroves & Mud Flats

With their dense vegetation, thick and often smelly mud, mangroves are not generally perceived to be particularly appealing habitats to visit. Yet this ecosystem has a diverse and fascinating flora and fauna, and plays a critical role in the conservation of the coast and the productivity of the sea.

Mangroves and Mudflats

"Where else can one find trees which walk out over the water and grow roots upwards, seeds which germinate before they fall from the parent tree, fish which hop about in the mud and climb trees, and monkeys which eat crabs?" (Thom Henley, 1998)

Mangroves thrive in sheltered bays where rivers have deposited nutrient-rich sediment. Mangrove trees can withstand severe environmental stress including alternating mixes of fresh and salty water, prolonged submersion or exposure with every tide, and mud that has no oxygen and a high sulphur content.

In her beautiful book on "Wild Thailand", Belinda Stewart-Cox describes how mangroves survive this difficult environment: "Mangrove trees survive in this environment because they have evolved specialised features. For example, tree roots do not grow deep into the mud, but spread wide and intertwine, forming a dense mat above and below the mud, securing themselves against forceful tides. Some mangrove trees have also developed breathing roots (pneutomatophores) which unlike most roots grow upwards out of the mud. These have pores which take in the oxygen necessary for making food and for eliminating salt from the water absorbed by other roots. Other trees, such as Sonneratia, expel salt through their leaves."

Knee- or finger-like pneumatophores (Luttge, U., 1997, Physiological Ecology of Tropical Plants)

An interesting and informative, yet technical, chapter on mangroves can be found in this book. Clicking on the image above will take you to the amazon.com page where you can read about or buy the book.

A walk through a mangrove forest is made difficult by these very adaptations to the changing environment which the mangrove trees must survive. Nonetheless, mangrove forests are the home to many large and small animals. For, while South Thailand�s mangroves may have lost their two largest predators, the tiger, and the estuarine crocodile, there remain many splendid creatures of which the lucky may still catch a glimpse.

"Among the species most commonly observed are: langurs feeding on leaves, civets feeding on fruit, crab-eating macaques, monitor lizards, cobras, the black and yellow mangrove snake, the small-clawed and hairy-nosed otters, fishing cats, brown-winged and ruddy kingfishers, masked finfoot, chestnut-bellied malkoha, buffy fish owl, brahminy kites, and the rare mangrove pitta." (Thom Henley, 1998).

But in fact it is not these fauna that make this ecosystem so vitally important. Rather, the richest life is in the mud. Mangroves play a critical role as the "oceans� nursery ground" for the sea�s fish, shrimp larvae, crabs and crustacea.

Sadly, mangroves have often been regarded, by non-local developers, as wasteland habitat, and large areas have been cleared throughout South-east Asia, either to create additional building land, or to convert into shrimp and coastal fish farms. These developments have been recent and rapid - over 50% of the original area of mangrove forest has been destroyed in just the last 30 years. The largest single cause of mangrove clearance has been for aquaculture purposes, particularly shrimp farms which experienced a massive boom in the early �80s to the early �90s.

Less than 1,500 square kilometres of mangrove forests are left in Thailand, most of which lie along the west peninsular coast from Ranong to Satun. Just 99 square kilometres of this vital habitat are currently protected, or approximately 3% of the original area.

The Andaman coast is blessed with the healthiest mangrove areas of all of Thailand, though even here the trees show little of their former grandeur. Nowadays, few trees reach more than 10 metres in height. Constant cutting by charcoal burners serves to prevent any from reaching their full height of over 20 metres. Mangrove forests may seem dense and impenetrable now, but an undisturbed forest would be further blessed with dozens of epiphytes in the upper branches. The solid trunk of a full-grown mangrove tree can reach 3 metres and more in circumference.

Mangrove forest and limestone peaks in Krabi. Almost no tall trees are left because of the constant pressure of harvesting for charcoal.

The coastal people of Thailand have long cherished the mangroves as a source of foods, medicine and fuel. Medicines include treatments for lumbago, skin diseases, VD and impotency. The Nipa Palm, a species which marks the transition from fresh to saline waters is used for everything from water proof roof-thatching to cigarette wrappings. Villagers even produce a weak wine from mangrove trees to celebrate special occasions.

Mudflats

Mud flats or tidal flats are also held in poor regard by many visitors to the coast. In fact, in Thailand, mud flats are in many places part of the mangrove system, being areas not yet colonised by the salt-tolerant trees. They are important feeding grounds for molluscs and marine invertebrates that crawl into the thick shifting sediments, emerging from their burrows to feed when the tide is in. They also attract millions of shore birds, including migrating and over-wintering waders. Over 40 coastal species of birds use the mud flats of Thailand. Bird watching enthusiasts will be very familiar with the significance of tidal mud flats for shore birds throughout the world, not just in Thailand.

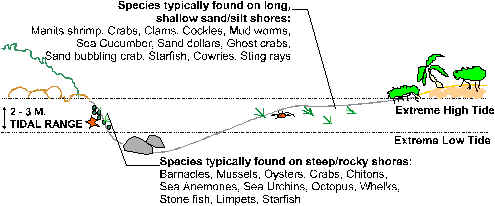

Adapted from an illustration in Reefs to Rainforests by Thom Henley

When the tide is out, a slow walk along tidal flats can bring many joys. Many species of crab, mantis shrimp, clams, mussels, sea cucumbers, urchins, and starfish live in the tidal zone, halfway between land and sea. It is an area rich in nutrients, brought in with the tides, and rich in food for man and other animals, including the smooth coated otter and sea turtles.

Undoubtedly, it is man and man�s activities that pose the greatest threats to the living communities of the tidal zone. High population pressure on food resources can lead to local (or global) extinctions of some creatures. Hunting for living shells for the tourism industry has serious effects on the balance of ecosystems on and off shore. Pollution from coastal developments and aquaculture has devastating impacts on intertidal communities. Bacteria use all the oxygen in the decomposition of the flood of organic matter passed over the muds, causing the intertidal creatures to suffocate to death. Large scale resorts with no road access often use the tidal flats to deliver goods. The action of bulldozers and other heavy machinery crushes the living bodies beneath the mud surface.

These muddy zones we often dismiss as unattractive wastelands serve a critical role for many organisms we cherish, and come perhaps the closest to reflecting the environment where life on the land first evolved. They have served human populations as a treasure of food and other resources for thousands of years, and today continue to provide the quiet joys of discovery of the many wonderful creatures living in the mud. Yet they are constantly under threat from developers who view them as unsavoury and unworthy of conservation, and from people using the resources of the tidal zone unwisely.

Key protected areas of tidal mud flats in Thailand include Koh Libong Wildlife Sanctuary, Khao Sam Roi Yot National Park, Pak Phanang Estuary and Tarutao National Park. Major unprotected sites include the Bay of Bandon, the mouth of the Mae Khlong and Tha Chin rivers, and inlets between Ranong and the Laem Son National Park. Sadly, even in the protected areas such as Khao Sam Roi Yot National Park, it is still necessary for conservationists to battle fiercly to conserve these areas� protected status and to prevent increasing encroachment along their boundaries.

Links to Further Information on Mangroves

| Environmental Education in the Mangroves | A Bangkok Post feature on an environmental education centre in Petchaburi which brings children and their teachers closer to the mangroves and raises awareness of their importance |

| Man in the Mangroves: The Socio-economic Situation of Human Settlements in Mangrove Forests | A United Nations University Press book which you can read on or download from the internet. |

| Mangrove Conservation and Development | A university course site with lots of links to organisations involved with mangrove conservation and research |

| Silviculture of Mangroves | Quite a technical paper looks at the potential for cultivating mangroves and managing these systems in a sustainable manner |

| World Conservation Monitoring Centre information and resources on mangroves | One of several sites provided by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, with a brief overview of mangrove habitats and maps of their global distribution. |

E-mail us: