Leanne Jardine-Tweedie, Phillip C. Wright

Leanne Jardine-Tweedie, NB Prescription Drug Program, Department of Health & Community Services, Fredericton, Canada

Phillip C. Wright, National Economics University, Hanoi, Vietnam

This paper discusses the use of drugs in the workplace with particular enphasis on the practice of drug testing, outlining arguments, both for and against. We conclude that drug testing tends to destroy the employee-employer relationship, recommending strongly not to engage in the practice. Finally, alternatives to drug testing are outlined, culminating in a call to place greater emphasis on performance testing.

Article type: Case Study.

Keywords: Drug Abuse, Employee Relations, Performance.

Content Indicators: Research Implications* Practice Implications*** Originality* Readability***

Journal of Managerial Psychology

Volume 13 Number 8 1998 pp. 534-543

Copyright © MCB University Press ISSN 0268-3946

Few topics generate as much debate and controversy as workplace drug testing. Opinions range from complete support to absolute rejection. Arguments concerning the safety of employees, the public and the environment, are pitted against the perceived need to protect employee privacy. These strong opinions, however, may have been formed because drug testing often is considered as a stand alone programme, as opposed to one possible component of a comprehensive drug and alcohol policy (Butler, 1993).

Workplace drug testing has not been embraced in other industrialized countries with the same enthusiasm or on the same scale as in the USA. Here, employer groups most likely to use drug testing are found in safety-sensitive industries and in the transportation sector where testing is required by law. In contrast to the USA, most other countries do not have specific laws about drug and alcohol testing. Deciding on whether or not to implement a testing programme, therefore, requires careful consideration of the benefits and the risks (Mehra, 1995).

Should companies in other countries follow the lead of the USA? This paper will argue that drug testing is one component of a workplace alcohol and drug abuse policy that is undesirable and unnecessary, in view of other available alternatives. Indeed, we will illustrate that drug testing can severely disrupt the operation of a modern business enterprise.

The extent of alcohol and drug use by the employed is not well known, as survey participants are reluctant to admit to using illegal drugs and alcohol at work. On the one hand, it has been suggested that illegal drug use at work is not prevalent. Conversely, studies conducted by the British Columbia Trucking Association and Transport Canada, suggest the workplace closely resembles society as a whole, in terms of alcohol and drug use. As a result, alcohol is by far the most common drug implicated in workplace accidents. Even though far less is documented or known about the role of illicit drugs, often the focus of drug-testing tends to be here, while alcohol and therapeutic medications often are ignored (MacDonald et al., 1993; Moyer, 1994).

Indeed, some researchers argue that the use of legal drugs poses a greater threat to health and safety than illegal substances, as both illicit drugs and medications have the capacity to impair job performance. Because the use of prescription drugs is more widespread, however, it has been suggested that legal drug use is a much greater threat to job safety than illicit drugs. There is a growing body of scientific information on impairment and the dangers resulting from the use and misuse of various therapeutic medications. All substances, then, have the potential for misuse or abuse (tranquillizers, sleeping pills and painkillers) - there are few exceptions (Shain, 1994).

In a 1992 Report on Drug and Alcohol Testing in the Workplace, the Ontario Law Reform Commission took the position that substance abuse was an "American problem" of no relevance to the Canadian context. Several other Canadian sources, however, indicate that drug abuse is one of Canada's most serious health and social problems - one of the leading causes of preventable death and illness (Moyer, 1994; Substance Abuse Policy in Canada, 1996).

Health Canada's Alcohol and Other Drugs Survey (1995), found that almost five million Canadians (20.8 per cent) use one or more of five targeted prescription drugs: tranquillizers, diet pills, antidepressants, sleeping pills and pain medications. The survey also looked at the use of the following illegal drugs: cannabis (marijuana/hash); cocaine; LSD; speed (amphetamines); and/or heroin. One or more of these illegal drugs has been used by 23.9 per cent of the population, or almost one in four Canadians at some point in their lives (Health Canada, 1995).

Cannabis is the most commonly-used illegal drug with 23.1 per cent of Canadians reporting use sometime in their lives and current use (past 12 months) reported at 7.4 per cent of the population - compared to 23.2 per cent and 6.5 per cent respectively in 1989. The per centage of respondents who reported using either cocaine or crack at least once at sometime in their lives was 3.8 per cent, while the number of current users appears to have dropped to 0.7 per cent of the population from 1.4 per cent in 1989. As well, more than one quarter million Canadians (1.1 per cent) are current users of one or more of LSD, speed or heroin, a rise of 0.7 per cent from 1989. After a decade of decline, therefore, indications are that illicit drug use is rising slightly (Substance Abuse Policy in Canada, 1996).

This national survey shows that although substance use/abuse has not reached epidemic levels in Canada, neither is it only an "American problem". Even at the levels reported in the most recent national survey, substance abuse has an unacceptable impact on the health and safety of Canadians and a high social and financial cost to society (Moyer, 1994).

In the North American context, the economic costs of substance abuse is staggering. It is estimated that drug abuse costs US industry and the public $100 billion in annual losses. A study conducted by the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA) estimated that substance abuse cost the Canadian economy more than $18.4 billion in 1992. This figure represents $649 per capita or 2.7 per cent of total Gross Domestic Product (Montoya and Elwood, 1995; Single et al., 1996; Twing, 1995).

In addition, the authors of these reports have taken a very conservative approach to estimating the costs of substance abuse. Total costs could be significantly higher, in that there are many hidden costs that cannot be quantified, e.g. diverted supervisory and managerial time, poor decisions, friction among workers, turnover, damage to an employer's public image and damage to equipment (Twing, 1995).

Drugs and alcohol alter a person's body functions, behaviour, personality and, therefore, work performance. When functions such as motor skills, reaction time, sensory and perceptual ability, attention, concentration, motivation and learning ability are affected, the result can be a decrease in accuracy, efficiency, productivity, worker safety and job satisfaction. It has been suggested, for example, that a chemically dependent employee usually is less than 75 per cent effective (Butler, 1993).

Thus, most workplace accidents are the result of human error. When an employee is impaired by drugs, alcohol, stress or fatigue, the potential for error increases tenfold (Leonard, 1996).

The main argument given for the use of employee drug testing is to ensure workplace safety, security and productivity. Proponents believe testing is necessary to protect the health and safety of workers and the public, from errors made by impaired workers. Drug testing is touted as a deterrent, since a positive test can result in loss of or denial of employment. It is also argued that testing is a useful rehabilitation tool when used to monitor compliance with a treatment programme. In addition, some employers implement testing programmes to reduce their legal liability for any harm caused to the public as a result of an employee-caused accident (Solomon and Usprich, 1993).

This philosophy has been adopted by many American firms. A study by the American Management Association found that a majority of US firms are now testing employees for drug use, in that 81.1 per cent of companies have workplace drug testing, compared to 21.5 per cent in 1987. In contrast, little is known about the prevalence of drug testing programmes outside the US (1996 AMA Survey; MacDonald et al., 1993; Swotinsky, 1992).

Is following the American course inevitable for other nationalities? For some international industries, such as transportation, the answer may be yes. American regulations under a 1991 law have been extended to foreign companies operating in the USA. By July 1997, for example, Canadian motor carrier companies operating either in the USA or providing contracting services to American companies, were subject to American drug testing requirements (Smythe, 1996).

One argument against alcohol and drug testing is that the process is intrusive and an unnecessary invasion of privacy. In addition, because the level of illicit drug use in many countries is low, testing all employees is a highly-intrusive approach to a problem that affects a relatively small segment of the population (Charlton, 1994; Oscapella, 1994).

As well, there is a lack of scientific evidence linking alcohol and drug use to negative consequences in the workplace. Much of the evidence suggesting that drug use is associated with increased accidents and decreased performance is based on laboratory studies showing that motor coordination and perceptual abilities fall with the ingestion of impairing drugs. Emerical field studies are few and have numerous limitations, making the evidence of relationships between usage and industrial accidents or performance problems, inconclusive. Indeed, numerous other factors are associated with workplace accidents and injuries - dangerous working conditions, noise and dirt, conflicts, stress, fatigue and sleep problems (MacDonald, 1995; MacDonald et al., 1993; Leonard, 1996).

Although a high correlation has been shown between breathalyser and blood tests for alcohol and the level of impairment and with accident and performance, tests for other drugs have limited value because they reveal only past drug use and cannot identify present impairment. In fact, drug tests detect only the presence of drug metabolites (byproducts), which for some drugs means the drug use could have occurred up to three weeks prior to the test (MacDonald et al., 1993; Oscapella, 1994).

Labour unions too, often object strongly to drug testing programmes. Many union executives believe that testing damages management/labour relations and draws attention away from accidents and other causes of productivity decline. They also point out, that there are many less intrusive ways to improve and ensure safety in the workplace. Similarly, opposition to testing has come from legal, medical, human rights, privacy and civil liberties groups (Butler, 1994).

There is little argument that alcohol, illicit drugs and legitimately-prescribed prescription drugs all have the potential to cause problems in the workplace. Drug testing programmes in the USA tend to focus on alcohol and illicit drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, opiates (heroin and morphine), phencyclidine (PCP) and amphetamines. As suggested earlier, however, many prescription and non-prescription drugs also have the potential to impair performance.

Various technologies are used to test for the presence of drugs and alcohol: breathalysers, urinalysis, blood, hair and saliva tests. The most popular and widely-used method of drug testing is urinalysis, which is also considered to be the most invasive (Harris and Heft, 1992).

Drug testing can be conducted in a number of different ways:

There are three possible consequences for job applicants or employees who test positive. If drug testing occurs prior to employment, the job applicant usually is not hired. With other types of screening, employees who test positive usually either are dismissed, or given the opportunity to obtain rehabilitation or treatment.

The dismissal option has disadvantages for both parties. When a person is dismissed, the employer must hire and train a new employee. The dismissed employee may have difficulty securing new employment and may not receive treatment even if there has been a perceived drug "problem". As well, depending on the jurisdiction, dismissal may have legal ramifications. The treatment option, therefore, is not only a more humanitarian approach to dealing with drug problems, but reduces the likelihood the employee will grieve or sue for wrongful dismissal.

Few scientific studies have been conducted to determine whether or not testing programmes reduce possible work difficulties resulting from alcohol and drug use. Furthermore, the available data do not produce sufficient evidence to show that alcohol and drug testing programmes improve productivity and safety in the workplace (International Labour Office, 1997).

Although testing accuracy has improved significantly, false positive, false negative and inaccurate tests still can occur. Most test procedures search for the presence of drug byproducts. These byproducts also are produced after ingestion of common foods and "over the counter" medications. Poppy seeds used on bagels, for example, can produce the same byproducts as heroin. Some prescription drugs can produce the same byproducts as cannabis. False positives also have been attributed to herbal teas, asthma or allergy medication, Vicks inhalers and diet aids. Higher levels of melanin pigment found in persons of colour are chemically similar to the active ingredient in marijuana and can indicate positive results even when there is no drug abuse (Weir, 1994).

False negatives - tests that fail to detect the actual use of drugs - also can occur. Employees sometimes spend a significant amount of time trying to avoid detection by using methods such as the purchase of "clean" urine. This substance then is carried under the arm in a squeezable container attached to a plastic tube.

Aside from possible inaccuracy and the resulting legal ramifications, drug screening can have a number of other negative consequences. Deterioration of the work environment can occur through fear, mistrust, polarization between management and workers and lack of openness. It has been reported, too, that employees who are subject to random drug testing become very negative in their relations with their employer and obviously, loyalty suffers. In addition to undermining labour-management relations, drug testing programmes can hinder recruitment, as potential employees may hesitate to join a firm with so little regard for employee privacy.

The first step in evaluating whether or not management should consider drug testing is to determine the objectives and to consider if drug testing will accomplish them. Employers should carefully weigh the issues related to drug testing: economic costs, laboratory and procedural issues, impact and effectiveness, possible adverse effects of intervention, and the various other legal implications. Thus, drug testing needs to be subject to the same careful analysis as other HRM initiatives.

In progressive organizations, the supervisor-employee relationship has evolved and changed significantly. Traditional supervision techniques have been replaced by empowered employees and self-directed work teams. Employee involvement and participation are encouraged. Many employers have recognized the advantages of giving employees control over their work. This practice results in a "win-win" situation for both employees and employers, leading to increased job satisfaction and enhanced organizational effectiveness.

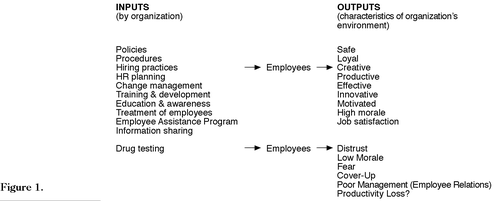

By trial and error, over several decades, it has been found that inputs (Figure 1) designed to increase self-esteem, employee autonomy and mutual respect are key ingredients in the development of an effective enterprise. For the most part, if the organizational inputs are right, the desired outputs will be achieved. Including drug testing as an input in this model would significantly change the outputs. Drug testing gives the employer absolute power over the employee. Thus, testing would significantly undermine employee trust and be contrary to the concept of empowerment and good management.

If the ultimate goal of drug screening in the workplace is to reduce accidents, other approaches may be more effective. As there are multiple causes of alcohol and drug-related problems, a number of approaches should be applied. Alternatives to drug testing have been suggested by both the Canadian Labour Congress and the Canadian Medical Association (Charlton, 1994; Drug Testing in the Workplace, 1992).

1. Train supervisors to detect performance problems that may affect safety. Supervisors use different techniques in dealing (or not dealing) with substance abuse. Some have taken a wait-and-see attitude, others actively cover-up for the employee, sometimes for extended periods of time and still others take the stance that either the employee improves work habits, or be fired. These approaches usually indicate that the supervisor does not know how to deal effectively with substance abuse. Furthermore, they are detrimental to everyone: the employee, supervisor, company and potentially the public (Twing, 1995).

To help the supervisor, a formal performance management system can provide a means of problem identification. Supervisors must be trained to recognize substance abuse symptoms and to know what action to take. Thus, supervisors are responsible for:

The initial signs of substance abuse often can be overlooked as insignificant, but the more serious signs have long been known: mood swings, slower work pace, less productivity, low reliability and poor attendance. The results are missed deadlines, excuses for not getting the job done and accidents. Conflict and morale problems can develop among co-workers. Complaints also increase from co-workers and customers regarding quality, timeliness and attitude (Wright, 1983).

Problems in the workplace that lead to stress and fatigue (which contribute directly to drug and alcohol use) should be eliminated where possible. These problems include excessive overtime, unsafe working conditions, boring repetitive tasks and poorly planned shift work (Charlton, 1994).

One American study has suggested that it costs between $7000-$10,000 to replace a production employee. Implementing ways of helping substance-dependent employees, then, obviously is more cost-effective than firing as a means of dealing with the problem (Twing, 1995). Indeed, in many jurisdictions, it has become extremely difficult to dismiss an employee.

2. Educational and awareness programmes. It is important to educate employees. Sessions can be delivered formally, by external resources, or by trained supervisors, or employee volunteers (Butler, 1994).

Topics that should be covered include:

Substance abuse, then, should be considered a health issue (Drug Testing in the Workplace, 1992).

3. Employee assistance programmes (EAP). EAPs are confidential company-sponsored programmes designed to help employees to identify and to resolve personal issues which may affect their well-being or job performance. EAP professionals also can provide a consulting service to managers and supervisors, helping them to deal with employees when job performance, safety or well-being is affected by personal difficulties. These programmes are an essential component of a comprehensive approach to workplace substance abuse, as a well-administered EAP can provide both prevention and rehabilitation services (Solomon and Usprich, 1993; Coshan, 1994).

4. Performance testing. Performance testing, much less intrusive than drug testing, may be an option in some workplaces. Job performance programmes generally are computer-based tests that check an employee's visual acuity, co-ordination and reaction time. Although these tests may not detect drug use, they could be useful for detecting performance deficiencies, the main goal of most drug testing programmes. Although performance tests seem to have merit, their effectiveness has not been widely studied. This area of research, however, is developing rapidly (Butler, 1994).

Indeed, this approach may be a large part of the answer to drug abuse in areas where public safety is of concern. Pilots, for example, could be required to take a computerized reaction and visual ability test before each flight. Not only would this approach "catch" drug abusers, but the pilot with the flu might be identified as well - neither should be flying. If proper (confidential) records were kept, even long-term deterioration in reflex time and other physical or mental attributes could be tracked. Most important, however, the performance test is not physically intrusive or humiliating. Thus, most of the negative aspects of drug testing, are avoided.

Managers should not test their employees for drugs - find an alternative! Drug testing runs counter to everything we know about good management practice! Testing is a negative input (Figure 1) that destroys any pretence of creating a productive work environment.

Figure 1 Element 1

1996, AMA Survey: Workplace Drug Testing and Drug Abuse Policies, 1996, American Management Association, New York, NY.

Butler, B., 1994, "Developing an alcohol and drug policy", Canadian Law Journal, 2, 484-515.

Butler, B., 1993, Alcohol and Drugs in the Workplace, Butterworths, Scarborough.

International Labour Office, 1997, Drug and Alcohol Testing in the Workplace: Guiding Principles, http://www.ccsa.ca/ilopubs.tm.

Drug testing in the workplace", 1992, Canadian Medical Association Journal, 146, 2232A.

Health Canada. Canada's Alcohol and Other Drugs Survey", 1994, 1995, Highlights Report, 1-5.

Mehra, K.K., 1995, "A testing time for examiners", Managerial Auditing Journal, 10, 6, 7-8.

Single, E., Robson, L., Xiaodi, X., Rehm, J., 1996, "The costs of substance abuse in Canada", Highlights Report.

Smythe, M.A., 1996, "Substance use: the countdown to compliance", Canadian Trucking Association (CTA) Magazine.

Solomon, R.M., Usprich, S.J., 1993, "Employment drug testing", Business Quarterly, 73-8.

Substance Abuse Policy in Canada, 1996, a presentation to the House Standing Committee on Health.

Swotinsky, R.B., 1992, The Medical Review Officer's Guide to Drug Testing, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, NY.

Weir, J., 1994, "Drug testing: a labour perspective", Canadian Law Journal, 2, 451-60.

Wright, P., 1983, "How managers should approach alcoholism and drug abuse in the workplace", Business Quarterly.