Argentina

Argentina or Argentine Republic, federal republic in southern South America, bounded on the north by Bolivia and Paraguay; on the east by Brazil, Uruguay, and the Atlantic Ocean; on the south by the Atlantic Ocean and Chile; and on the west by Chile. The country occupies most of the southern portion of the continent of South America and is somewhat triangular in shape, with the base in the north and the apex at Punta Dungeness, the southeastern extremity of the continental mainland. The length of Argentina in a northern to southern direction is about 3330 km (about 2070 mi); its extreme width is about 1384 km (about 860 mi). The country includes the Tierra del Fuego territory, which comprises the eastern half of the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego and a number of adjacent islands to the east, including Isla de los Estados. The area of Argentina is 2,766,889 sq km (1,068,302 sq mi); it is the second largest South American country, Brazil ranking first in area. Argentina, however, claims a total of 2,808,602 sq km (1,084,120 sq mi), including the Falkland Islands, or Islas Malvinas, and other sparsely settled southern Atlantic islands, as well as part of Antarctica. The Argentine coastline measures about 5000 km (about 3100 mi) in length. The capital and largest city is Buenos Aires.

Land and Resources

This unusual formation, called Fitz Roy Hill after its discoverer, is part of the southern Andes Mountains, in the Argentine province of Santa Cruz. The entire western border of Argentina lies within the Andes range.

Argentina National Tourist Office

Argentina comprises a diverse territory of mountains, upland areas, and plains. The western boundaries of the country fall entirely within the Andes, the great mountain system of the South American continent. For considerable stretches the continental divide demarcates the Argentine-Chilean frontier. The Patagonian Andes, which form a natural boundary between Argentina and Chile, are one of the lesser ranges, seldom exceeding about 3600 m (about 12,000 ft) in elevation. From the northern extremity of this range to the Bolivian frontier, the western part of Argentina is occupied by the main Andean cordillera, with a number of peaks above about 6400 m (about 21,000 ft). Aconcagua (6960 m/22,834 ft), the highest of these peaks, is the greatest elevation in the world outside Central Asia. Other noteworthy peaks are Ojos del Salado (6893 m/22,615 ft) and Cerro Tupungato (6800 m/22,310 ft), on the border between Argentina and Chile, and Mercedario (6770 m/22,211 ft). Several parallel ranges and spurs of the Andes project deeply into northwestern Argentina. The only other highlands of consequence in Argentina is the Sierra de Córdoba, situated in the central portion of the country. Its highest peak is Champaquí (2790 m/9153 ft).

Eastward from the base of the Andean system, the terrain of Argentina consists almost entirely of a flat or gently undulating plain. This plain slopes gradually from an elevation of about 600 m (about 2000 ft) to sea level. In the north the Argentine plains consist of the southern portion of the South American region known as the Gran Chaco. The Pampas, treeless plains that include the most productive agricultural sections of the country, extend about 1600 km (about 1000 mi) south from the Gran Chaco. In Patagonia, south of the Pampas, the terrain consists largely of arid, desolate steppes.

Rivers and Lakes

Iguaçu Falls, on the border between Argentina and Brazil, is one of South America’s great natural wonders. The falls range between 60 and 80 m (about 197 to 262 ft) high. In the dry season the river drops in two crescent-shaped falls, but in the wet season the water merges into one large fall more than 4 km (2.5 mi) wide.

Erika Stone/Photo Researchers, Inc.

The chief rivers of Argentina are the Paraná, which traverses the north central portion of the country; the Uruguay, which forms part of the boundary with Uruguay; the Paraguay, which is the main affluent of the Paraná; and the Río de la Plata, the great estuary formed by the confluence of the Paraná and the Uruguay rivers. The Paraná-Uruguay system is navigable for about 3000 km (about 2000 mi). A famed scenic attraction, the Iguaçu Falls, is on the Iguaçu River, of a tributary of the Paraná. Other important rivers of Argentina are the Río Colorado, the Río Salado, and the Río Negro. In the area between the Río Salado and the Río Colorado and in the Chaco region, some large rivers empty into swamps and marshes or disappear into sinks. The hydrography of the country includes numerous lakes, particularly among the foothills of the Patagonian Andes. The best known are those in the alpine lake country around the resort town of San Carlos de Bariloche (Bariloche).

Climate

Temperate climatic conditions prevail throughout most of Argentina, except for a small tropical area in the northeast and the subtropical Chaco in the north. In Buenos Aires the average temperature range is 17° to 29° C (63° to 85° F) in January and 6° to 14° C (42° to 57° F) in July. In Mendoza, in the foothills of the Andes to the west, the average temperature range is 16° to 32° C (60° to 90° F) in January and 2° to 15° C (35° to 59° F) in July. Considerably higher temperatures prevail near the tropic of Capricorn in the north, where extremes as high as 45° C (113° F) are occasionally recorded. Climatic conditions are generally cold in the higher Andes, Patagonia, and Tierra del Fuego. In the western section of Patagonia winter temperatures average about 0° C (32° F). In most coastal areas, however, the ocean exerts a moderating influence on temperatures.

Precipitation in Argentina is marked by wide regional variations. More than 1520 mm (60 in) fall annually in the extreme north, but conditions gradually become semiarid to the south and west. In the vicinity of Buenos Aires annual rainfall is about 950 mm (about 37 in). In the vicinity of Mendoza annual rainfall is about 190 mm (about 7 in).

Natural Resources

The traditional wealth of Argentina lies in the vast Pampas, which are used for extensive grazing and grain production. However, Argentine mineral resources, especially offshore deposits of petroleum and natural gas, have assumed increasing importance in recent decades.

Plants and Animals

The indigenous vegetation of Argentina varies greatly with the different climate and topographical regions of the country. The warm and moist northeastern area supports tropical plants, including such trees as the palm, rosewood, lignum vitae, jacaranda, and red quebracho (a source of tannin). Grasses are the principal variety of indigenous vegetation in the Pampas. Trees, excluding such imported drought-resistant varieties as the eucalyptus, sycamore, and acacia, are practically nonexistent in this region and in most of Patagonia. The chief types of vegetation in Patagonia are herbs, shrubs, grasses, and brambles. The Andean foothills of Patagonia and parts of Tierra del Fuego, however, possess flourishing growths of conifers, notably fir, cypress, pine, and cedar. Cacti and other thorny plants predominate in the arid Andean regions of northwestern Argentina.

In the north the fauna is most diverse and abundant. The mammals in these regions include several species of monkeys, jaguars, pumas, ocelots, anteaters, tapirs, peccaries, and raccoons. Indigenous birds include the flamingo and various hummingbirds and parrots. In the Pampas are armadillos, foxes, martens, wildcats, hare, deer, American ostriches or rheas, hawks, falcons, herons, plovers, and partridges; some of these animals are also found in Patagonia. The cold Andean regions are the habitat of llamas, guanacos, vicuñas, alpacas, and condors. Fish abound in coastal waters, lakes, and streams.

Soils

The soils of Argentina vary greatly in fertility and suitability for agriculture, and water is scarce in many areas outside the northeast and the humid Pampas. The Pampas, which are largely made up of a fine sand, clay, and silt almost wholly free from pebbles and rocks, are ideal for the cultivation of cereal. In contrast, the gravelly soil of most of Patagonia, in southern Argentina, is useless for growing crops. The natural grasslands of this region are used primarily as pasture for sheep. Most of the northern Andean foothill region is unsuitable for farming, but several oases favor fruit growing. In part of the Chaco an unusually saline soil is believed to be responsible for the abundance of the tannin-rich quebracho trees.

Population

About 85 percent of the population is of European origin. Unlike most Latin American countries, Argentina has relatively few mestizos (persons of mixed European and Native American ancestry), although their number has increased in recent times. European immigration continues to be officially encouraged; from 1850 to 1940, some 6,608,700 Europeans settled in the country. Spanish and Italian immigrants have predominated, with significant numbers of French, British, German, Russian, Polish, Syrian, and other South American immigrants. More than one-third of the population lives in or around Buenos Aires; about 87 percent of the people live in urban areas.

Ushuaia, on Argentina’s island of Tierra del Fuego, is the world’s southernmost city. Argentina claims part of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, including the largest island, known as Tierra del Fuego or Great Island, and Staten Island. Chile claims the remainder of the islands in the territory.

Population Characteristics

According to the 1991 census, Argentina had a population of 32,663,983. The 1996 estimated population is 34,672,997, giving the country an overall population density of about 13 persons per sq km (about 33 per sq mi) in 1996.

Political Divisions

Argentina comprises 23 provinces; the self-governing Distrito Federal (Federal District), which consists of the city of Buenos Aires and several suburbs; the Argentine-claimed sector of Antarctica; and several South Atlantic islands.

The provinces are grouped into five major areas: the Atlantic Coastal, or Littoral, provinces, comprising Buenos Aires (excluding the city of Buenos Aires), Chaco, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Formosa, Misiones, and Santa Fe; the Northern provinces, comprising Jujuy, Salta, Santiago del Estero, and Tucumán; the Central provinces, comprising Córdoba, La Pampa, and San Luis; the provinces of the Andes, or Andina, comprising San Fernando del Valle de Catamarca, La Rioja, Mendoza, Neuquén, and San Juan; and the Patagonian provinces, comprising Chubut, Río Negro, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego.

A number of nations, including the United States, do not recognize the Argentine claim to the vast sector of Antarctica, between longitude 25° West and 74° West, and to a number of South Atlantic islands.

Principal Cities

Buenos Aires is the capital of Argentina and its largest city. The Plaza de Mayo, seen here, is at the heart of the downtown area. The city originated at this point in the 16th century and grew in ever-widening circles.

Daniel I. Komer/DDB Stock Photography

Buenos Aires is Argentina’s capital and largest city. At the 1991 census the metropolitan area population was 10,686,163. Other important cities include Córdoba (population, 1991, 1,148,305), a major manufacturing and university city; the river port of Rosario (894,645); La Plata (520,647), capital of Buenos Aires Province; Mar del Plata (519,707), a resort city at the mouth of the Río de la Plata; San Miguel de Tucumán (470,604), a diversified manufacturing center; Salta (367,099), famous for its colonial architecture; and Mendoza (121,739), hub of an important agricultural and wine-growing region.

Language

Spanish is the official language and is spoken by the overwhelming majority of Argentines. Italian and a number of Native American languages are also spoken.

Religion

Roman Catholics make up more than 92 percent of the population. Judaism, Protestantism, and a number of other Christian and non-Christian religions are practiced. By law, the president and vice president of Argentina must be Roman Catholic.

Education and Culture

Argentina is a nation with a rich Spanish heritage, strongly influenced since the 19th century by European, notably Italian, immigration. A lively interest is maintained in the nation’s history, particularly as symbolized by the gaucho (cowboy). In the fine arts, the most important model has been France; only in folk art has there been significant influence from Native American cultures.

Education

Primary education is free and compulsory from ages 6 to 14. In the early 1990s about 4.9 million pupils attended primary schools; 2.2 million attended secondary and vocational schools. Nearly 1.1 million were enrolled in colleges and universities. Argentina’s literacy rate of about 95 percent is one of the highest in Latin America.

Argentina has 25 national universities and many private universities. The principal institution is the University of Buenos Aires (1821). Other major national universities are the Catholic University of Argentina (1958), National Technological University (1959), National University of Córdoba (1613), and other universities located in Bahía Blanca (1956), La Plata (1905), Mendoza (1939), San Miguel de Tucumán (1914), and Rosario (1968).

Libraries and Museums

The leading library of Argentina is the National Library (1810) in Buenos Aires, which has about 1.9 million volumes. Prominent among the many museums in Buenos Aires are the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences, the National Museum of Fine Arts, and such private collections as the International Art Gallery. The Museum of La Plata is famous for its collections of reptile fossils.

Literature

Argentine literature, originally a derivative form of Spanish literature, took on a markedly nationalistic flavor in the 19th century. The poem Fausto (1866), by Estanisláo del Campo, is a gaucho version of the Faust legend; El gaucho Martín Fierro (1872; The Departure of Martin Fierro, 1935), a narrative poem on gaucho life by José Hernández, is considered by many the national epic of Argentina; and finally, the sociological essay Facundo (1845; translated 1868), by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, is a study of how the rural life of the Argentine Pampas helped shape the national character.

Twentieth-century Argentine literature has produced the celebrated Shadows in the Pampas (1926; translated 1935), a novel by Ricardo Guiraldes; Hopscotch (1963; translated 1966), a novel by Julio Cortázar; The Kiss of the Spider Woman (1976; translated 1979), a novel by Manuel Puig; and the stories of Ernesto Sábato. Eduardo Mallea, a novelist who wrote on existentialist themes, and Jorge Luis Borges, internationally renowned for his short stories, are major contemporary figures. The best-known poet is Leopoldo Lugones, who wrote both symbolist and naturalist verse.

Art

Buenos Aires, founded in 1580 on the west bank of the Río de la Plata, is Argentina’s capital and most populous city. It is also one of the world’s largest cities. In the early 1990s, about 10.7 million people—more than one-third of the country’s population—lived in the greater Buenos Aires area.

Painting in the 19th century was dominated by gaucho themes and scenes of town life. Prilidiano Pueyrredón was the principal artist of the period. Painters of the 20th century include the realist Cesareo Bernaldo de Quirós; Benito Quintela Martín, painter of port life in Buenos Aires; the cubist Emilio Pettoruti; and Raul Soldi. The works of the sculptor Rogelio Yrurtia are widely known.

Music

The most important components of traditional Argentine music are the gaucho folk song and folk dance; Native American music from the northern provinces; European influences; and, to a minor extent, African music. The tango, which developed in Buenos Aires and became a favorite ballroom dance throughout much of the world, is perhaps Argentina’s most famous contribution to modern music. Astor Piazzolla, a prolific 20th-century tango composer, bandleader, and performer, incorporated jazz and classical influences in his works.

Symphonic music and opera are important features of cultural activity. The National Symphony Orchestra is based in Buenos Aires, and the opera company of the city is housed in the Colón Theater, built in 1908. The Colón opera has achieved an international reputation for excellence. Leading figures in the classical music field are three brothers, José María Castro, Juan José Castro, and Washington Castro, all conductors and composers. Alberto Williams, the founder of the Buenos Aires Conservatory, was the best known of all Argentine composers. Alberto Ginastera is well known for his symphonic, ballet, operatic, and piano music, which is popular throughout the world.

Economy

The Argentine economy is based primarily on the production of agricultural products and the raising of livestock, but manufacturing and mining industries have shown marked growth in recent decades. Argentina is one of the world’s leading cattle- and grain-producing regions; the country’s main manufacturing enterprises are meat-packing and flour-milling plants. Argentina’s estimated annual national budget in 1994 called for revenue of about $48.46 billion and expenditure of $46.5 billion. Argentina’s estimated gross domestic product (GDP) in 1994 was $281.9 billion.

Agriculture

Livestock farming is a significant economic activity in Argentina. Pasture lands for sheep and cattle occupy more than 50 percent of the country, and animal products, particularly wool, are a major export. Here, a sheep farmer gathers his flock in Patagonia, where 40 percent of the country’s sheep are raised.

Victor Englebert/Photo Researchers, Inc.

Argentina raises enough agricultural products not only to fill domestic needs but also to export surpluses to foreign markets. Of Argentina’s land area of about 280 million hectares (about 692 million acres), about 52 percent is used for pasturing cattle and sheep herds, about 22 percent for woodland, and about 4 percent for permanent crops; about 9 percent of the country’s land area is arable. The Pampas is the most important agricultural zone of the country, producing wheat and cereal grains. Irrigated areas, from the Río Negro north through Mendoza, San Juan, San Miguel de Tucumán, and Jujuy, are rich sources of fruit, sugarcane, and wine grapes.

Livestock raising and slaughtering are major enterprises in Argentina, as are the refrigeration and processing of meat and animal products; total annual meat production is nearly 3.5 million metric tons, three-quarters of it from cattle. In the early 1990s there were some 50 million head of cattle, 23.7 million sheep, and 4.8 million pigs in Argentina. In addition, there were about 3.3 million horses; Argentine horses have won an international reputation as racehorses and polo ponies.

Livestock export plays an important role in foreign trade. Earnings from meat, hides, and live animal exports in the late 1980s were about $1.4 billion, annually, or about 14 percent of total export earnings. Argentina has long ranked as the world leader in the export of raw meat. Cooked and canned meats are increasingly important exports.

Large quantities of wool are produced and exported; in the early 1990s, about 202,200 metric tons of wool were produced per year, out of a world total of about 2.9 million metric tons. About 40 percent of all sheep in Argentina are raised in the Patagonia region.

Wheat is the most important crop. Argentina is among the major producers of wheat in the world. In the early 1990s, the annual wheat crop totaled about 9.4 million metric tons. Other major cash crops were maize (10.7 million metric tons), soybeans (11.3 million), and sorghum (2.8 million). Other major field crops include oats, barley, flaxseed, sunflower seeds, sugarcane, cotton, potatoes, rice, maté, peanuts, and tobacco, as well as a considerable crop of grapes, oranges, lemons, and grapefruit.

Forestry and Fishing

Argentina’s fisheries have steadily increased production during the past three decades. Shown here are shrimp-fishing baskets and boats at Mar de Plata Port, in the province of Buenos Aires, along the Atlantic coastline of Argentina.

Carlos Boldin/DDB Stock Photography

Situated mainly in mountain areas distant from centers of population, the 59.5 million hectares (147 million acres) of woodland are relatively unused. Among the most exploited woods are elm and willow, for cellulose production; white quebracho, for fuel; red quebracho, for tannin (used for tanning leather); and cedar, for the manufacture of furniture. Other economically important woods are oak, araucaria, pine, and cypress.

Argentina’s fisheries, potentially highly productive, have not been fully exploited, although production increased steadily in the 1960s and 1970s. In the early 1990s the annual catch was about 640,000 metric tons—about two-thirds of which was Argentine hake.

Mining

Although the country has a variety of mineral deposits, including petroleum, coal, and a number of metals, mining has been relatively unimportant in the economy. In recent decades, however, production of petroleum and coal, in particular, has increased significantly. In terms of value, the chief mineral product is petroleum. In the early 1990s annual production of crude petroleum was about 203 million barrels, furnishing the country’s needs and allowing Argentina to become a net energy exporter. In September 1995 Argentina and Great Britain signed a joint agreement covering oil and gas exploration in a specially designated zone southwest of the disputed Falkland Islands. The two countries agreed to establish a commission that would oversee the licensing of companies seeking to explore the waters, the division of royalties, and the implementation of worker safety and environmental protection measures. The next month, Argentina began auctioning oil exploration licenses for areas just outside the disputed waters, between Argentina and the Falklands. Argentina also produces significant amounts of natural gas. Relatively small quantities of coal, iron ore, gold, silver, lead, zinc, tin, tungsten, mica, and limestone are mined.

Manufacturing

Most industry is centered in Buenos Aires. About one-fifth of the national labor force is employed by manufacturing establishments. The country’s oldest industry is the processing and packaging of foodstuffs. By the early 1990s the production of petroleum products had exceeded food processing in value. Other manufactures, ranked by value, were textiles, transportation equipment, industrial chemicals, and iron and steel.

Energy

Most rivers and falls with potential energy are located far from industrial centers, but despite these technical limitations water resources are being developed in Argentina at a rapid rate. Major hydroelectric projects undertaken in the 1970s and 1980s were located in northern Patagonia, the Yacyretá Dam and other sites on the Paraná River, and on the Uruguay River (in cooperation with Uruguay). The first of 20 generators at Yacyreta were activated in 1994. While most electricity is generated by hydro-electric power, Argentina has one of the most advanced nuclear programs in Latin America, providing 13 percent of the country’s electrical needs. Overall, 51.3 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity were generated yearly in the early 1990s, from an installed capacity of 17.9 million kilowatts.

Currency and Banking

Formerly, Argentina’s monetary system was based on the peso oro (Spanish "gold peso"), although no gold coins actually circulated. The peso moneda nacional (called the paper peso and consisting of 100 centavos) was the currency in use. Rampant inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s rapidly depreciated the value of the peso, and in June 1985 a new currency, the austral (equal to 1000 pesos), was introduced as part of an ambitious program to control inflation. When this failed, the nuevo peso argentino (equal to 10,000 australs) was introduced in January 1992, at an exchange rate of 1 peso equaling U.S.$1. In 1996 1 Argentinian peso was still trading for U.S.$1.

The Central Bank, which was established in 1935 and came under government control in 1949, functions as the national bank and has the sole right to issue currency. In the mid-1980s, 30 other banks were government owned, and about 30 commercial banks were in the private sector operating on a national level.

Commerce and Trade

The trade balance tends to be favorable to Argentina when world demand for food is high. In the early 1990s, however, an economy recovering from recession boosted demands for imports and Argentina recorded a trade deficit. Annual exports were worth about $12.7 billion, principally meat, wheat, corn, oilseed, hides, and wool. Imports were worth $16 billion and included machinery and equipment, chemicals, metals, fuels and lubricants, and agricultural products. Chief trading partners were the United States, Brazil, Germany, and Japan. Regional trade with other Latin American countries is governed by the Latin American Integration Association (LAIA), of which Argentina is a member. Argentina is also a member of the Southern Cone Common Market (also known by its Spanish acronym, MERCOSUR). Founded in 1995, MERCOSUR eliminates tariffs on many goods traded between Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

Transportation

The entire Argentine railroad system was owned and operated by the government from 1948 until 1992, when portions of the rail system were privatized. By 1994, most of the state-owned rail network had been privatized. The system has a total length of about 34,172 km (about 21,234 mi). Two different gauges are used. Two lines crossing the Andes provide a connection with points in Chile; railroad links also connect Argentina with Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil. As a result of privatization, service to some areas of the country is unavailable.

Aerolíneas Argentinas was the national airline until it was privatized in 1990. There are also several smaller, internal airlines. About 11,000 km (about 6800 mi) of waterways are provided by navigable rivers, especially those in the Río de la Plata region. The combined length of all roads and highways is about 208,350 km (about 129,470 mi). A railroad tunnel through the Andes has provided facilities for motor vehicles since its expansion in 1940. In the early 1990s some 4.3 million passenger cars and 1.5 million commercial vehicles were registered.

Communications

A postal service extending to the entire country is maintained by the government. More than 4.6 million telephones are in use. In the early 1990s some 22.6 million radios were in use in Argentina, and television sets numbered about 7.3 million.

About 190 daily newspapers are published in Argentina, although the principal ones are published in Buenos Aires and circulate throughout the country. La Prensa and La Nación, with circulations of about 65,000 and 211,000, respectively, are famed internationally for their independent views and objectivity. Other leading Buenos Aires papers are Clarín (daily circulation 480,000), Crónica (520,000 in two editions), Página 12 (220,000) and La Razón (180,000). The provincial capitals and other secondary centers all have daily papers with strong local followings. A number of magazines containing both news and features are published in Buenos Aires and circulate throughout the country.

Labor

In the early 1990s the total labor force numbered about 12.3 million. Most of Argentina’s 1100 labor unions are affiliated with the Confederación General del Trabajo (General Labor Confederation), known as the CGT. The right to unionize, suspended in 1976, was restored in 1982, and the labor movement included about 3 million workers by the late 1980s. By the early 1990s privatization programs had resulted in the loss of several hundred thousand jobs and an unemployment rate of 10 percent (1.3 million unemployed).

Government

According to the constitution of 1853, Argentina is a federal republic headed by a president, who is assisted by a council of ministers. Legislative powers are vested in a national congress consisting of a Senate and a House of Deputies. A new constitution was passed in 1949, only to be rescinded in 1956. All constitutional provisions were suspended in 1966 following a military takeover. After another military coup in 1976, the constitution of 1853 was again suspended, but it was reinstated when Argentina returned to civilian rule in 1983. The constitution of 1853, in the preamble and in much of the text, reflects the ideas and aims of the Constitution of the United States. Several parts of Argentina’s constitution were revised in 1994.

Executive

Argentina’s 1853 constitution invested executive power in a president elected to a single six-year term. The presidential mandate allowed for executive participation in drawing up legislation, as well as the execution of laws. The revised 1994 constitution reduced the presidential term to four years, allowed the president to seek a second consecutive term, and assigned some formerly presidential powers to the legislature. The president serves as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Legislature

The organization of the legislature of Argentina is similar to that of the United States. The National Congress consists of a lower chamber, the 257-member House of Deputies, and an upper chamber, the 72-member Senate. Deputies are elected directly to four-year terms by a system of proportional representation. Each province elects three senators to six-year terms. Two of these senators are directly elected and the third represents the province’s largest minority party. Three senators represent the city of Buenos Aires. The 1994 constitution gave some formerly presidential powers to the legislature. An office similar to that of a prime minister and controlled by the legislature was created to exercise those powers. All citizens 18 years of age or older are entitled to vote.

Local Government

Under the constitution, the provinces of Argentina elect their own governors and legislatures. During periods when the constitution has been suspended, provincial governors have been appointed by the central government.

Judiciary

Federal courts include the Supreme Court, 17 appellate courts, and district and territorial courts on the local levels. The provincial court systems are similarly organized, comprising supreme, appellate, and lower courts.

Health and Welfare

The National Institute of Social Welfare has administered most Argentine welfare programs since its founding in 1944. Health services are provided to workers by the various unions and to others by free hospital clinics. Medical standards are relatively high in the cities, and efforts are constantly being made to improve medical facilities located in outlying rural areas.

Defense

The Argentine military establishment is one of the most modern and best equipped in Latin America and has historically played a prominent part in national affairs. Drastic cuts in military spending in the 1990s, however, prompted Argentina’s armed forces to initiate a number of profit-making ventures in order to raise money, including offering tours of Patagonia on navy ships. Military conscription was abolished in 1995. In the mid-1990s the army had a strength of about 40,400 men. The navy consisted of an aircraft carrier, six missile-equipped destroyers, and a number of lighter ships and submarines; it had a strength of about 20,500 men. The air force, with 8900 men, had about 150 combat aircraft, including jet fighters and bombers.

History

Compared to the Native American populations in the Andes and the Amazon region, the area of South America that is now Argentina was sparsely populated before the arrival of Spanish explorers in the 1500s. Some of these inhabitants were members of nomadic tribes, while others were engaged in agriculture.

In February 1516, the Spanish navigator Juan Díaz de Solís, then engaged in search of a southwest passage to the East Indies, piloted his vessel into the great estuary now known as the Río de la Plata and claimed the surrounding region in the name of Spain. Sebastian Cabot, an Italian navigator in the service of Spain, visited the estuary in 1526. In search of food and supplies, Cabot and his men ascended the river later called the Paraná to a point near the site of modern Rosario. They constructed a fort and then pushed up the river as far as the region now occupied by Paraguay. Cabot, who remained in the river basin for nearly four years, obtained from the natives quantities of silver. The river system was named Río de la Plata (Spanish for "river of the silver") after the precious metal found there.

Early Settlements

Colonization of the region was begun in 1535 by the Spanish soldier Pedro de Mendoza. In February 1536, Mendoza, who had been appointed military governor of the entire continent south of the Río de la Plata, founded Buenos Aires. In its efforts to establish a permanent colony, the Mendoza expedition encountered severe hardships, chiefly because of difficulties in obtaining food. Hostile natives forced the abandonment of this settlement five years later.

In 1537 Domingo Martínez de Irala, one of Mendoza’s lieutenants, founded Asunción (now the capital of Paraguay), which was the first permanent settlement in the La Plata region. From their base at Asunción, the Spanish gradually won control over the territory between the Paraná and Paraguay rivers. The small herds of livestock brought from Spain had meanwhile multiplied and spread over the Pampas, creating the conditions for a stable agricultural economy.

Santiago del Estero, the first permanent settlement on what is now Argentine soil, was established in 1553 by Spanish settlers from Peru. Santa Fe was founded in 1573, and in 1580 the resettlement of Buenos Aires was begun. In 1620 the entire La Plata region was attached to the viceroyalty of Peru for administrative purposes. Because of the restrictive commercial policies of the Spanish government, colonization of the La Plata region proceeded slowly during the next 100 years. Buenos Aires, the center of a flourishing trade in smuggled goods, grew steadily. By the middle of the 18th century, its population numbered close to 20,000. In 1776 the territory occupied by present-day Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay was separated from Peru and incorporated as the viceroyalty of La Plata.

Patriotic Awakening

In June 1806, Buenos Aires was attacked by a British fleet under the command of Admiral Home Riggs Popham. The viceroy offered no defense against the attack, which was made without authorization by the British government. The invaders occupied the city but were expelled by a citizen army the following August. An expeditionary force subsequently dispatched by the British government against Buenos Aires was compelled to capitulate in 1807. These events had far-reaching consequences: the colonial patriots, imbued with confidence in their fighting ability, soon became active in the independence movement that had begun to develop in Spanish South America.

Revolutionary sentiment in La Plata reached its peak in the period following the deposing of King Ferdinand VII of Spain by Napoleon in 1808. The people of Buenos Aires refused to recognize Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, who was then installed on the Spanish throne. On May 25, 1810, they overthrew the viceregal government and installed a provisional governing council in the name of Ferdinand VII. The provisional government shortly broke with the representatives of Ferdinand and launched an energetic campaign to revolutionize the La Plata hinterland. This campaign ended in failure. Several signal victories, however, were won over invading royalist armies in 1812 and 1813. The liberated part of the viceroyalty was divided into 14 provinces in 1813. In 1814 the brilliant military leader José de San Martín took command of the northern army, which later struck decisive blows against Spanish rule in Chile and Peru.

The United Provinces

During 1814 and 1815 sentiment crystallized in the liberated area, which was nominally still subject to the Spanish crown, in favor of absolute independence. Representatives of the various provinces convened at Tucumán in March 1816. On the following July 9 the delegates proclaimed independence from Spanish rule and declared the formation of the United Provinces of South America (later United Provinces of the Río de la Plata). Although a so-called supreme director was appointed to head the new state, the congress was unable to reach agreement on a form of government. Many of the delegates, particularly those from the city and province of Buenos Aires, favored the creation of a constitutional monarchy. This position, which was later modified in favor of a highly centralized republican system, met vigorous opposition from the delegates of the other provinces, who favored a federal system of government. Friction between the two factions mounted steadily, culminating in a civil war in 1819. Peace was restored in 1820, but the central issue, formation of a stable government, remained unresolved. Throughout most of the following decade a state of anarchy, further compounded by war with Brazil from 1825 to 1827, prevailed in the United Provinces. Brazil was defeated in the conflict, a result of rival claims to Uruguay, which emerged as an independent state.

The national political turmoil lessened appreciably after the 1829 election of General Juan Manuel de Rosas as governor of Buenos Aires Province. A federalist, Rosas cemented friendly relations with other provinces, thereby winning broad popular support. He rapidly extended his authority over the United Provinces, which became known as the Argentine Confederation, and during his rule all opposition groups were crushed or driven underground.

Republican Government

The dictatorial regime of Rosas was overthrown in 1852 by a revolutionary group led by General Justo Urquiza, a former governor of Entre Ríos Province, who received assistance from Uruguay and Brazil. In 1853 a federal constitution was adopted, and Urquiza became first president of the Argentine Republic. Buenos Aires Province, refusing to adhere to the new constitution, proclaimed independence in 1854. The mutual hostility of the two states flared into war in 1859. The Argentine Republic won a quick victory in this conflict, and in October 1859, Buenos Aires agreed to join the federation. The province was, however, the center of another rebellion against the central government in 1861. Headed by General Bartolomé Mitre, the rebels defeated the national army in September of that year. The president of the republic resigned on November 5. In May of the next year a national convention elected Mitre to the presidency and designated the city of Buenos Aires as the national capital. With these events, Buenos Aires Province, the wealthiest and most populous in the union, achieved temporary control over the remainder of the nation.

Turmoil in Uruguay brought on a Paraguayan invasion of Argentine territory in 1865, beginning the bloody War of the Triple Alliance, which ended in complete victory for Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay in 1870. During the next decade the conquest of the Pampas as far as the Río Negro was completed, and the threat of hostile Native Americans from that direction was eliminated. This so-called War of the Desert (1879-1880), directed by General Julio A. Roca, opened up vast new areas for grazing and farming. In 1880 Roca, who opposed the ascendency of Buenos Aires in national affairs, was elected to the presidency. In the aftermath of his victory, the city of Buenos Aires was separated from the province and established as a federal district and national capital. A long-standing boundary dispute with Chile was settled in 1881; through this agreement Argentina acquired the title to the eastern half of Tierra del Fuego. In 1895 a boundary dispute with Brazil was submitted to arbitration by the United States, which awarded about 65,000 sq km (about 25,000 sq mi) of territory to Argentina. The country became involved in a serious controversy with Chile regarding the Patagonian frontier in 1899. This dispute was finally settled in 1902, with Great Britain acting as arbitrator.

In the half century following 1880, Argentina made remarkable economic and social progress. During the first decade of the 20th century the country emerged as one of the leading nations of South America. It began to figure prominently in hemispheric affairs and, in 1914, helped to mediate a serious dispute between the United States and Mexico. Argentina remained neutral during World War I (1914-1918) but played a major role as supplier of foodstuffs to the Allies.

Depression and Turmoil

The world economic crisis that began in 1929 had serious repercussions in Argentina. Unemployment and other hardships caused profound social and political unrest. Economic conditions improved substantially during the administration of General Augustín Justo, but political turbulence intensified, culminating in an unsuccessful Radical uprising in 1933 and 1934. In the period preceding the presidential elections of 1937, Fascist organizations became increasingly active. In May 1936, following the organization of a left-wing Popular Front, the Argentine right-wing parties united in a so-called National Front. This organization, which openly advocated establishment of a dictatorship, successfully supported the finance minister, Roberto M. Ortiz, for the presidency. Contrary to the expectations and demands of his supporters, however, Ortiz took vigorous steps to strengthen democracy in Argentina. Countermeasures were adopted against the subversive activities of German agents, who had become extremely active after the victory of National Socialism in Germany. The corrupt electoral machinery of the country was overhauled. Ortiz proclaimed neutrality after the outbreak of World War II in 1939, but he subsequently cooperated closely with the other American republics on matters of hemispheric defense.

World War II

In July 1940, President Ortiz, unable to function because of illness, designated Vice President Ramón S. Castillo as acting president. A Conservative, Castillo broke with the foreign and domestic policies of his predecessor. At the Pan-American Defense Conference, held at Rio de Janeiro in January 1942, shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Argentina and Chile were the only American nations to refuse to sever relations with the Axis powers.

Castillo, who had officially succeeded to the presidency following the resignation of Ortiz in June 1942, was removed from office one year later by a military group headed by General Arturo Rawson, who favored severance of relations with Germany and Japan. On the eve of his assumption of office as provisional president, however, Rawson’s associates forced him to resign. The provisional presidency went to General Pedro Ramírez, one of the leaders of the revolt. Ramírez shortly abolished all political parties, suppressed opposition newspapers, and generally stifled the remnants of democracy in Argentina. In January 1944, in a complete reversal of foreign policy, his government broke diplomatic relations with Japan and Germany.

Fearful that war with Germany was imminent, a military junta, the so-called Colonels, forced Ramírez from office on February 24, 1944. The central figure in the junta was Colonel Juan Domingo Perón, chief of labor relations in the Ramírez regime. Despite protestations of sympathy with the Allied cause, the government continued the policy of suppression of democratic activity and of harboring German agents. In July the U.S. government accused Argentina of aiding the Axis powers. Finally, on March 27, 1945, when Allied victory in Europe was assured, the country declared war on Germany and Japan. In the following month the government signed the Act of Chapultepec, a compact among American nations for mutual aid against aggressors. Argentina, with U.S. sponsorship, became a charter member of the United Nations in June. Shortly afterward, it was announced that elections would be held early in 1946.

The Perón Era

Revival of political activity in Argentina was marked by the appearance of a new grouping, the Peronistas. Formally organized as the Labor Party, with Perón as its candidate for the presidency, this group found its main support among the most depressed sections of the agricultural and industrial working class. The Peronistas campaigned among these workers, popularly known as descamisados (Spanish for "shirtless ones"), with promises of land, higher wages, and social security. The elections, held on February 24, resulted in a decisive victory for Perón over his opponent, the candidate of a progressive coalition.

In October 1945, Perón married the former actress Eva Duarte. As first lady of Argentina, Eva Perón managed labor relations and social services for her husband’s government until her death in 1952. Adored by the masses, whom she manipulated with consummate skill, she was, as much as anyone, responsible for the popular following of the Perón regime. In October 1946, President Perón promulgated an ambitious five-year plan for the expansion of the economy. During 1947 he deported a number of German agents and expropriated about 60 German firms. After these moves, relations between Argentina and the United States improved steadily.

New Constitution

In March 1949, Perón promulgated a new constitution permitting the president of the republic to succeed himself in office. Taking advantage of the new law, the Peronista Party in July 1949 renominated Perón as its presidential candidate for 1952. As a result, the opposition parties and press became increasingly critical of the government. The Peronista majority in the congress retaliated in September of that year with legislation providing prison terms for people who showed "disrespect" for government leaders. Many opponents of the regime were jailed in subsequent months. The congress shortly instituted other retaliatory measures, notably suppression of the opposition press.

La Prensa, a leading independent daily newspaper, was suppressed in March 1951. In the following month, congress approved legislation expropriating the paper. Severe restrictions were imposed on the anti-Peronista parties in the campaign preceding the national elections, which took place in November 1951, instead of in February 1952, the originally scheduled date. President Perón was reelected by a large majority, and Peronista candidates won 135 of the 149 seats in the house of deputies.

Second Term

In January 1953 the government inaugurated a second five-year plan. The plan emphasized increased agricultural output instead of all-out industrialization, which had been the goal of the first five-year plan. During 1953 Argentina concluded important economic and trade agreements with several countries, notably Great Britain, the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and Chile. Foreign commercial transactions in 1953 produced a favorable balance of trade, the first since 1950; but inflationary pressures, which had resulted in an increase in the cost of living of more than 200 percent since 1948, did not lessen.

In November 1954, Perón accused a group of Roman Catholic clergymen of "fostering agitation" against the government. Despite church opposition, the government proposed and secured enactment during the next two months of legislation legalizing absolute divorce, granting all benefits of legitimacy to children borne out of wedlock, and legalizing prostitution. The schism between church and state widened steadily in the succeeding months.

Overthrow

On June 16, 1955, dissident elements of the Argentine navy and its air arm launched a rebellion in Buenos Aires. The army remained loyal, however, and the uprising was quickly crushed. Tension increased during the next few weeks, as factions within the government and the military maneuvered for position. Finally, on September 16, insurgent groupings in all three branches of the armed forces staged a concerted rebellion; after three days of civil war, during which approximately 4000 people were killed, Perón resigned and took refuge on a Paraguayan gunboat in Buenos Aires Harbor. On September 20 the insurgent leader Major General Eduardo Lonardi took office as provisional president, promising to restore democratic government. Perón went into exile, first in Paraguay and later in Spain.

Provisional Presidents

In less than two months the Lonardi government was itself overthrown in a bloodless coup d’état led by Major General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu. The announced reason for the revolt was the unwillingness of Lonardi to suppress Peronism, especially in the army and among the workers. Aramburu abrogated the 1949 constitution and restored the liberal charter of 1853. Under the latter, a president may not succeed himself. A Peronist revolt was crushed in June 1956. Thousands were arrested, and 38 alleged Peronistas were executed. Scores of people were subsequently imprisoned on charges of plotting to overthrow the new regime.

Elections to a constitutional assembly were held in July. The moderate Radical Party, headed by Ricardo Balbín, received the most votes, closely followed by the somewhat leftist Intransigent Radical Party under Arturo Frondizi. The Peronistas, forbidden to function as a party, were instructed by their exiled leader to cast blank ballots. Blanks, which were encouraged also by some minor groups, exceeded the votes of any single party and constituted about one-fourth of the total cast.

Elected Presidents

The constituent assembly, which opened in Santa Fe in September, unanimously readopted the constitution of 1853 after the Intransigent Radicals and some others withdrew. When general elections were held in February 1958, Frondizi won the presidency with Peronist and Communist support, and his Intransigent Radical Party won a majority in the legislature. Representative government was restored on May 1.

Despite labor unrest and continual rises in living costs, a degree of economic stability was achieved in early 1959 with the aid of substantial foreign loans and credits; by 1960, loans from U.S. public and private agencies alone amounted to $1 billion. Argentina’s participation in the Latin American Free Trade Association (LAFTA), founded in 1960, helped foster a growing trade with other countries in the region from 1960 to 1980.

Frondizi’s popularity declined markedly throughout 1961. In elections held in March 1962, Peronistas, again permitted electoral participation, polled about 35 percent of the total vote. Although Frondizi forbade five successful Peronist candidates from assuming the provincial governorships they had won, he was deposed at the end of the month by military leaders critical of his leniency toward Peronism. José María Guido, as president of the Senate, became Frondizi’s constitutional successor.

His government, however, was dominated by the armed forces. Both Peronistas and Communists were barred from the national elections of July 1963, in which Arturo Illía, a moderate of the People’s Radical Party, was elected president. Illía announced a program of national recovery and regulation of foreign investment and tried to control rising prices, shortages, and labor unrest by fixing prices and setting minimum-wage laws.

Military Rule

In elections in 1965, Peronist candidates made significant gains, although Illía’s party retained a 71-seat plurality in the lower house. Labor unrest continued into 1966, and the Peronistas continued to win victories in by-elections. The result was a military coup in June 1966. The junta that then took control named succeeding presidents, the third of whom, General Alejandro Augustín Lanusse, took office in 1971.

In the early months of his regime, Lanusse began moving toward a return to civilian rule. He announced an economic program designed to hold down the inflationary spiral, and scheduled national elections for March 1973. In 1972, however, the country became increasingly torn by violence, including strikes, student riots, and terrorist activities. The economy too was headed for a new crisis. The Peronistas had grown increasingly vocal, and they now nominated Perón for the presidency. He remained in Spain until after the date set for candidates to be resident in Argentina, however, and Hector J. Cámpora was nominated in his place.

Return and Death of Perón

Peronistas swept the elections in March 1973, and Cámpora was inaugurated as president on May 25. Terrorism escalated, now joined by rightist vigilantes, with numerous kidnappings, soaring ransom demands, and killings. Divisions between moderate and leftist Peronistas also brought widespread violence. On June 20, when Perón returned to Buenos Aires, a riot resulted in approximately 380 casualties.

A month later Cámpora resigned, and in September Perón was elected president, with more than 61 percent of the votes. His third wife, Isabel de Peron, was elected vice president.

The strain, however, proved too much for the aging Perón. He died on July 1, 1974, and his wife succeeded him, becoming the first woman chief executive of a modern Latin American state. During her presidency, political and economic conditions deteriorated rapidly. In 1975 terrorist activities by right- and left-wing groups resulted in the deaths of more than 700 people. The cost of living increased by 335 percent, and strikes and demonstrations for higher wages were frequent. After repeated cabinet crises and an abortive air force rebellion in December 1975, a military junta led by the army commander, Lieutenant General Jorge Rafael Videla, seized power on March 24, 1976. The junta dissolved the legislature, imposed martial law, and ruled by decree.

Military Rule and the Falklands War

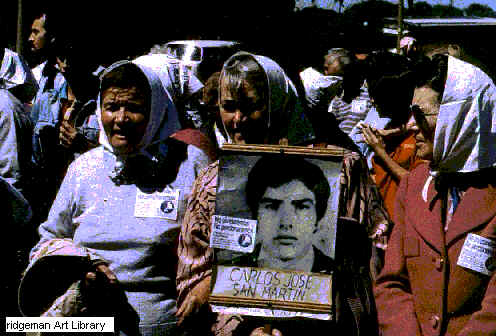

A group of Argentines, including this woman holding a picture of her son, gather on the streets of Buenos Aires, Argentina, to protest the abduction of their family members by the military-led government. Beginning in 1976, when a military junta seized power in the country, thousands of Argentines were seized by the military government in its attempt to quell left-wing opposition and terrorism. Many were imprisoned without trial, tortured, and killed, and thousands were never seen again by their families. Protesters of the terrorism adopted the name los desaparecidos (Spanish for "the disappeared ones").

Margaret Feitlowitz

For the first few months after the military takeover, terrorism remained rampant, but it waned somewhat after the Videla government launched its own terror campaign against political opponents. In 1977 the Argentine Commission for Human Rights, in Geneva, blamed the regime for 2300 political murders, some 10,000 political arrests, and 20,000 to 30,000 disappearances.

The economy remained chaotic. Videla was succeeded as president in March 1981 by Field Marshal Roberto Viola, himself deposed in December 1981 by the commander in chief of the army, General Leopoldo Galtieri. Galtieri’s government rallied the country behind it in April 1982 by forcibly occupying the British-held Falkland Islands (called Islas Malvinas by the Argentines). After a brief war Great Britain recaptured the islands in June, and the discredited Galtieri was replaced by Major General Reynaldo Bignone.

The Latin American Integration Association (LAIA), founded in 1980, replaced LAFTA as a more loosely defined entity for reducing tariffs on intracontinental trade. Between 1986 and 1990, Argentina signed a number of integration treaties designed to further reduce trade barriers between Latin American countries.

With an unprecedented international debt, and inflation at more than 900 percent, Argentina held its first presidential election in a decade in October 1983. The winner was the candidate of the Radical Party, Raúl Alfonsín. Under Alfonsín, the armed forces were reorganized; former military and political leaders were charged with human rights abuses; the foreign debt was restructured; fiscal reforms (including a new currency) were introduced; and a treaty to resolve a dispute with Chile over three Beagle Channel islands was approved. Inflation remained unchecked, however, and in May 1989 the Peronist candidate, Carlos Saúl Menem, was elected president. With Argentina’s economy deteriorating rapidly, Menem imposed an austerity program. During the early 1990s his government curbed inflation, balanced the budget, sold off state enterprises to private investors, and rescheduled the nation’s debts to commercial banks. In 1992 full diplomatic relations with Britain were restored, helping to heal the wounds of the Falklands War. In January 1994 the country signed the Treaty of Tlatelolco, making Argentina a nuclear weapons-free state. Also in 1994, leaders from Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay signed the Asunción treaty, which confirmed those countries’ intention to create the Southern Cone Common Market by the end of 1994. In 1994 Argentina adopted a new constitution. The most notable change shortened the presidential term from six to four years and allowed the president to seek a second consecutive term. In 1994 Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay signed a treaty that created the Southern Cone Common Market (also known by its Spanish acronym, MERCOSUR). The agreement took effect on January 1, 1995, allowing 90 percent of trade between member countries to proceed duty free. This agreement, combined with the privatization of state industries, helped Argentina to continue its economic recovery.

Carlos Saúl Menem won a second consecutive presidential term in May 1995. When it became clear later in the year that Argentina would have difficulty meeting fiscal targets for 1996 set by the International Monetary Fund, Menem called on the Argentine Congress to declare a state of economic emergency. In an effort to allow the president to raise funds quickly in the event of a budget crisis, Menem was granted emergency economic powers in March 1996 that gave him the power to raise tax rates and impose new taxes without congressional approval.

That same month more than 10,000 prisoners rioted across Argentina, taking dozens of hostages and instigating one of the worst prison rebellions in the country’s history. The rioting began at a maximum security prison in Buenos Aires, quickly spread to other prisons, and lasted for more than a week. Inmates, an estimated 70 percent of whom were awaiting trial, called for an end to overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, and for faster processing in the courts.

In July Menem dismissed Domingo Carvallo, the finance minister who guided Argentina’s economic policy in the early 1990s. Carvallo’s policy of deregulation and privatization brought lower inflation and economic stability to Argentina, but many government employees lost their jobs when government-owned businesses were privatized. Despite Carvallo’s dismissal, the government continued to follow his fiscal plan. Rising unemployment led labor organizers to call a general strike in September 1996 and in May 1997 violent protests against the government’s economic policies took place in cities and towns across the nation.

Menem reshuffled Argentina’s military leadership in October 1996, replacing three of the country’s top four military leaders. The president requested the resignation of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretaries of the Navy and Air Force, all of whom had shown signs of resisting Menem’s efforts to reform the military.

See: Perón, Eva, Perón, Isabel de, Perón, Juan Domingo