|

By ATIYA ACHAKULWISUT:

Bangkok Post May 15, 1998

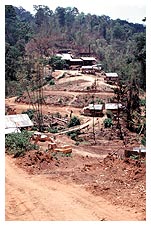

Phu Jue mine and Kao Lee mine (left) are both situated on the northern boundary of Thung Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, posing a threat to the fragile ecology right next door. |

ENVIRONMENT: Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary - one of Thailand's most beautiful nature reserves and a World Heritage site - is under threat from lead mining

"Only after the last tree has been cut down.

Only after the last river has been poisoned.

Only after the last fish has been caught.

Only then, will you find that money cannot be eaten."

Cree Indian prophecy

It may not have been written down as law. But it is tacitly understood that certain activities should not be conducted in the same or adjacent places. A butchery, for example, is not supposed to stand side by side with a delicatessen. Building latrines in the middle of a public waterway, upstream from where people bathe in and drink the water, would also be considered bad taste.

Why, then, do we tolerate mines on the boundary of our wildlife sanctuary? Since mining is extremely harsh on the environment, its existence totally defeats the purpose of setting aside an area as a wildlife sanctuary - a special place preserved for flora and fauna to live and propagate.

The truth is Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary, whose unique ecology earned it a listing as a World Heritage site, is literally besieged by lead mines. At least six are situated almost wall-to-wall with the sanctuary's borders. To the north in Kanchanaburi province are Phu Jue, Phu Mong and Kao Lee mines. On the southern side are clustered Klity, Bo Ngam, KEMCO (or Song Thor) and a number of other small and large-scale lead mines together with lead separation plants

Most of the mines are owned by Bhol and Son Co., Ltd or its subsidiaries, Kanchanaburi Exploration and Mining Co., Ltd and Lead Concentrate Co., Ltd.

"Having mines beside a wildlife sanctuary is unjustifiable from any perspective," a forestry official, who asked not to be named, commented. "Their existence poses a substantial threat to the fragile ecosystem. Mineral-transporting trucks, which regularly ply through the sanctuary, disturb wildlife. Waste discharge, often untreated, could also contaminate the sanctuary's water resources and wildlife habitat," the official said.

The mines may be located outside Thung Yai Naresuan Sanctuary, but the effects of their activities respect no boundary. Contamination from toxic discharge could spread far beyond the concessioned areas.

If we forget national boundaries and look at the larger picture, including the Burmese side of the border, these mines are sitting right in the middle of a large tract of pristine, tropical forest.

"Forest on both side of the Tenasserim range is so rich and unique that it deserves to be designated a transboundary protected area. There was an attempt once between Thailand and the Karen National Union to set up such a system. But it failed with the KNU's disintegration," the forestry official said.

Last month, villagers in Lower Klity village, downstream from Klity mine and lead separation plant, filed a complaint with the Pollution Control Department. The villagers protested that waste water from the mine has polluted their only water resource, the Huai Klity stream. The villagers' cattle and fowl fell ill or died after drinking water from the stream.

A subsequent investigation by the department revealed that the mine failed to treat its waste water and has illegally dumped it into the stream. A study by the Department of Mineral Resources in 1995 found that the mine excavated sediment from its waste water pond and dumped it outside the concession area. Unless properly taken care of, the possibly lead-laden waste could be washed away by rainfall and contaminate waterways and aquifer in the area, the study warned.

Following the complaint, Kanchanaburi's mineral resource office ordered the mine temporarily closed until its waste water facilities are improved. The Pollution Control Department dispatched a team to check the water and sediment in the Huai Klity area. The test results are not available yet.

In the meantime, environmentalists have protested that the temporary suspension of a single mine falls short of ensuring the long-term health of Thung Yai Naresuan.

"This is not the first time the Klity mine has been ordered closed," said Narong Jangkamol, a researcher at Seub Nakhasathien Foundation. "It has been shut down temporarily several times in the past when there were complaints or news about its pollution. Soon after the outcry subsided, the mine reopened."

Effluent flows into a retaining pond at Klity lead mine. According to a Department of Mineral Resources study, lead contamination downstream from the mine is as high as 552,380 parts per million. The safe standard is just 200 ppm. -- Pictures by SMITH SUTIBUT |

Since Klity mine serves only as a floatation unit, where lead is separated from other substances, tackling the problem here alone would not suffice. To obtain more comprehensive data, the environmental impact of a network of mines along the northern and southern border of Thung Yai Naresuan, which feed raw materials to the Klity mine, needs to be reviewed too.

Mr Narong pointed out that since sink holes, a typical feature of the province's limestone topography, are abundant in the mining areas, waste water in sedimentation ponds easily leaks out into surface and underground water resources.

Moreover, when KEMCO mine's huge tailing pond, with a capacity of 2 million cubic metres, proved to be ineffective in preventing waste seepage, the mine blocked Huai Chanee, a public stream, and turned it into a retaining pond. By doing so, KEMCO mine also benefits from the use of public water to dilute its waste.

According to the Mineral Resources Department's 1995 study, lead contamination in and around the mining areas is very high. For instance, the amount of lead in sediment in Huai Klity, downstream from the mine, is 165,720 to 552,380 ppm (part per million). The safe standard is 200 ppm.

Mr Suraphol Duangkhae, of Wildlife Fund Thailand, is another firm believer that a mine and a wildlife sanctuary do not go together. The repercussions of conducting both activities in adjacent areas is severe.

"The road that cuts through Thung Yai is accessible only during the dry season. Mineral transporting, therefore, must be done in a hurry during the limited time. Over twenty trucks have to make several trips back and forth right through the middle of Thung Yai every day."

Engine noise alone is enough to scare off wildlife, Mr Suraphol said. A forest ranger in Thung Yai observed that should the mineral trucks not travel through the sanctuary, gaurs or elephants would have roamed around more freely.

Tangible impacts from the mines' toxic waste are difficult to gauge, though.

"The effects may not be evident immediately. But lead contamination may be spreading slowly throughout the food chain. Also, we have never conducted an inventory of the wildlife in Thung Yai. Many of them might have perished without our knowledge," Mr Suraphol said.

Lead poisoning can cause nausea, numbness, central nervous system breakdown and sudden death in living organisms. If accumulated in the body, it can lead to severe headache, impotence and paralysis.

Mr Suraphol said that the forest in Kanchanaburi is home to such endemic species as Kitti bat, the smallest mammal in the world, and the Rajini crab. These animals are not found anywhere else on earth.

Mr Suraphol believed that many more endemic species, especially fish, are living somewhere in Thung Yai waiting to be discovered. They might have suffered terribly from mining-related waste or already be extinct, nobody knows.

The Wildlife Fund researcher also noted that applications to conduct studies in Thung Yai Naresuan are hardly ever approved. There might be some vested interests inside the sanctuary that the Forestry Department does not want outsiders to witness, he speculated.

Both Mr Suraphol and Mr Narong raised the point that impacts from mining may deteriorate the sanctuary's ecology to an extent that it loses the World Heritage status. A similar incident took place in the US. When the World Heritage committee knew of gold mining concessions near the Yellowstone National Park, it urged the US government to revoke them. And President Clinton did, even though he had to pay the concessionaire millions of dollars in compensation.

Siriporn Nanta, head of the Secretariat of Thailand's Committee for World Heritage Convention, however, said that we need not lose sleep over the issue.

"Our office has been concerned about continued mining activities near the World Heritage site and keeping a close watch," she said. "We are informed that these mines are only allowed to continue their operation until the end of their present concession. No renewal will be granted.

"I don't think transporting the mineral through the sanctuary will have that serious an effect. Some of the mines had been there before the sanctuary was declared. Their activities are nothing new to the area. We paid more attention to the fact that the road must not be developed further."

Ms Siriporn added that it is as difficult to be listed as a World Heritage site as to be deprived of the status, unless the problem is extremely threatening. So far, none of the World Heritage sites has been removed from the listing

A map of the area around Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary showing the five lead mines beieging its borders. -- SMITH SUTIBUT |

Naturally, there are people who believe that lead mines do serve a purpose. If nothing else, they generate income. Kanchanaburi is one of the few places in the country with large enough lead deposits for commercial exploration.

Lead mining in this province started in 1948. Most of the mineral is exported. The yearly output has grown from 13 metric tonnes when it first started to over 69,000 metric tonnes, worth 398 million baht, in 1988.

Considering the proximity of these mines to Thung Yai Naresuan and the mines' poor record in caring for the environment, however, one wonders if the benefit is worth the risk?

"The mine operators have reaped a lot of profit from the business. I think it is time they stopped prying open the earth and return the land to Nature," said a Karen villager, who suffers from the pollution from Klity mine.

Mr Suraphol also urged that no renewal of mining concession around protected areas be granted from now on. Those whose concessions are still valid must install the necessary equipment - a closed system for waste water recycling or lime stabilisation in case discharge needs to be released - to ensure that they do not pollute the surrounding area.

Since the Department of Mineral Resources' 1995 study proposed the same mitigation methods, to no avail, Mr Suraphol added that a neutral body, possibly consisting of local representatives, should be set up to implement the measures and monitor the mines' performance.

The bio-diversity of Thung Yai Naresuan is irreplaceable. Once it is gone, it is gone forever. We still have the time and resources to preserve it, so why don't we? After all, it is the interdependence of land, plants and animals that forms the core base of humanity's survival in the next millennium.

Or do we have to wait until the last tree is cut down and the last river poisoned to realise that we cannot eat money? Or lead.

| |

© 2000-2001 by Karen Studies and Development Centre. Report technical problems to [email protected] . This document was build on: 22/06/2001 . Best view in IE4x or higher,800x600 pix.Font Medium.

|