Writers

of railway history have not been kind to Edward Bury.

He has been derided as a builder of tiny, old-fashioned engines,

obstructively stuck in the past while greater men were pushing locomotive

development forward. He has been

accused of being too commercially-minded, wangling orders for his own firm from

railways which employed him as a manager. Any

grudging admission of his engines’ worth is always explained away be giving

the credit to his foreman and later partner, James Kennedy.

A

lot of this is unfair. Originating

in the railway power-politics of the 1830’s and 1840’s, this story was

nurtured by writers of the ‘Stephenson first, the rest nowhere’ school after

Bury was safely dead, and was widely propagated in the 1890’s by that creator

of so much railway mythology, Clement Stretton.

Since when, Bury’s low status has been taken for granted.

In

this year of his bicentenary some reassessment is overdue.

Edward

Bury, F.R.S., M.I.C.E., member of the Smeatonian Society, Fellow of the Royal

Astronomical Society, Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, was born in

Salford, Lancashire on 22nd October 1794, the son of a wealthy timber

merchant, and was given a good education at Chester.

In his youth he was something of a model engineer, and after a spell as a

partner in Gregson & Bury’s steam sawmills in Liverpool, he set himself up

there in 1826 as an engineer and ironfounder.

His

first locomotive Dreadnought, an 0-6-0

with horizontal outside 10” x 24” cylinders with an intermediate shaft and

chain drive to the wheels, was intended for the Rainhill Trials of October 1829,

but was not ready in time. It is

said to have had a cut-off valve and so was one of the earliest – perhaps the

first – locomotive to work expansively. It

did some ballasting on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, then under

construction, from March 1830 but was ‘much objected to’ because it was on

six wheels. It was sold to John

Hargreaves and thereafter worked on the Bolton & Leigh Railway.

Bury’s

second engine was a four-wheeler but the objection this time was the size of the

wheels: at 6' diameter they were described as ‘dangerous’ by the Liverpool

& Manchester’s Engineer, George Stephenson.

As originally built – it appeared in July 1830 – it has a boiler,

according to Edward Woods, ‘with a number of convoluted flues’ whatever that

means. Bury’s widow said it was a

modification of the French patent i.e. Marc Seguin’s multitubular boiler

patent of February 1828. After

rebuilding in May 1831 it had a boiler containing 131 tubes.

This engine, Liverpool,

established Bury’s standard design practice: simple wrought-iron bar frame

inside the wheels with only two bearings on each axle, horizontal inside

cylinders and a round firebox in the form of a vertical cylinder with a

hemispherical top and a grate with was D-shaped in plan.

The 6' coupled wheels were the largest seen up to that time, but after a

high-speed derailment at Atherton on the Bolton & Leigh line in July 1831,

they were reduced to 4' 6”. In

this form Liverpool can be seen

passing Parkside in one of the famous Ackermann ‘long-prints’ dated November

1831.

This

was a remarkable design then (when Stephenson and allied firms were using

outside wooden frames plus four internal sub-frames): it was obviously the

product of some serious thinking, and it lasted.

In gradually increasing sizes, the same frame design –

rectangular-section bars for the top members and round-section bars for the

bottom trusses – it was continued for twenty years.

From Bury’s exports to the U.S.A. the bar-frame became standard there. The domed-top firebox likewise increased in size over the

years; it too was taken up by American builders such as Norris, Rogers and

Baldwin and was used by them into the mid-1850s.

Some increase in grate area within the frame was possible in making the

base rectangular, but further enlargement meant the abandonment of the round box

altogether, as in Bury-built engines from 1848. The advantages of the large steam space in the Bury firebox

pointed these American builders in the direction of the wagon-top or taper

boiler (1850).

Bury

built a few more engines for local buyers (the Liverpool & Manchester would

take only one, Liver, their No. 26,

and insisted at Stephenson’s urging on outside frames) but an export trade

with the U.S. was quickly established. In

the 1830s Bury sold 28 engines there, more than any other British maker except

R. Stephenson & Co with 35. Bury

was the Stephensons’ biggest competitor at this period and they had good

reason to worry about him.

In

a trial between Bury’s Liver and

Stephenson’s Planet for six days in

June 1832 the Bury engine was found to do the same work while burning less coke

– 0·49 lbs per tone per mile against Planet’s

0·54 lbs – and this despite an attempt by a Stephenson partisan to feed Planet

with better coke while also screwing down its safety valves.

Bury

established himself at the Clarence Foundry & Steam Engine Works in Love

Lane, Liverpool, not far from the Clarence Dock and backing onto the Leeds &

Liverpool Canal. The works

eventually covered 3 acres and at its height employed 1600 men.

About 415 locomotives were manufactured there, as well as all manner of

other metal goods, from marine engines to church bells.

There was a separate boiler yard at the other end of Liverpool in

Harrington (now Cary) Street with a shipbuilding yard close by, off Sefton

Street. The Clarence Foundry had a

frontage to Love Lane of about 400 feet, south from the corner of Burlington

Street; the site today is covered by Eldonian Avenue, Jack McBain Court and some

other streets.

As

his foreman Bury took on James Kennedy (1797 – 1886) a millwright from

Edinburgh who had previously been with Stephenson in 1824/5 and Mather Dixon

& Co. from 1826. In 1842 Bury

made him a partner and with the addition of Timothy Abraham Curtis the firm was

thereafter known as Bury, Curtis & Kennedy.

It has been claimed that James Kennedy was the brother of the Rainhill

Trials judge, John Kennedy, but this is untrue.

One of Bury’s early fitters was James Edward McConnell, later of the

Birmingham & Gloucester Railway and the London & North Western Railway;

others were William Fernihough of the Eastern Counties Railway, William Paton of

the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway and Frederick Parker, Manager of Doncaster

Locomotive Works.

By

the standards of the time, the management was enlightened; an American visitor

in 1843 was surprised to find the working day was only ten hours with wages of

26 to 30 shillings a week. The

Clarence Foundry had a reputation for good workmanship, which is borne out by

the long life of many of its products.

Some

42 locomotives were built by Bury, Curtis & Kennedy for railways in Ireland:

thirty for the Great Southern & Western, four for the Belfast & County

Down, five for the Belfast & Ballymena and three for the Newry, Warrenpoint

& Rostrevor Railway. They were

all delivered between the years 1845 and 1849.

Edward

Bury’s name will always be associated with that of the London & Birmingham

Railway, but as with other aspects of his life, many misleading statements have

been made.

After

their experience with Stephenson & Co. certain Liverpool directors of the

London & Birmingham came to distrust the Newcastle firm.

In particular they disliked the Stephensons’ near-monopoly in

locomotive manufacture. They pushed

a rather reluctant Edward Bury into the position of contractor for locomotive

power. Under this contract the

L&B would buy engines as recommended by the contractor, who agreed to

maintain them and operate the trains at a fixed rate per mile. Before deciding on this ‘contract system’ for running

their line, the L&B Board had taken advice from experts in the field,

including Joseph Pease of the Stockton & Darlington and Robert Stephenson

himself. The replies were

encouraging: this seemed to be the most economical way to run a railway.

The

contract was signed in May 1836 and Bury prepared designs for passenger and

goods engines; sets of large-scale drawings and specifications were sent out to

locomotive builders who responded in some cases with offers to build. Bury wanted every engine to be exactly like every other,

though by different makers. This

was the very first scheme of standardisation of parts, despite claims which have

been made in this regard for Joseph Locke and Daniel Gooch. Sadly, he was far ahead of his time; the various firms would

not work to the drawings. Some

didn’t see why it was important. ‘Well,

it works, doesn’t it?’ was their attitude.

Engines by Benjamin Hick of Bolton were the best, according to Bury

‘extremely well made’; those by Hawthorn ‘less inaccurate than the

others’. Not only did some

engines deviate from the drawings, engines from the same maker differed from

each other. The wheels of an engine

by Maudslay, Son & Field of Lambeth ‘would not fit under any other on the

line’.

Bury

arranged for the coke and water arrangements along the line and in October 1836

selected the site for the Central Engine Repairing Station about half-way

between London and Birmingham where the rails were to cross the Grand Junction

Canal, near the village of Wolverton. This

works and its surrounding cottages became the first of the planned railway

towns, serving as a model for the later Crewe and Swindon.

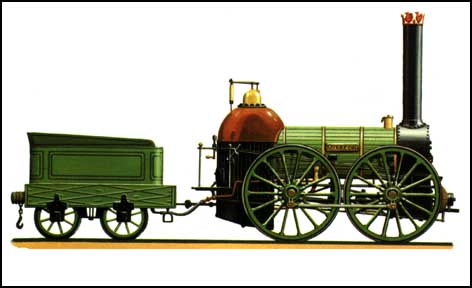

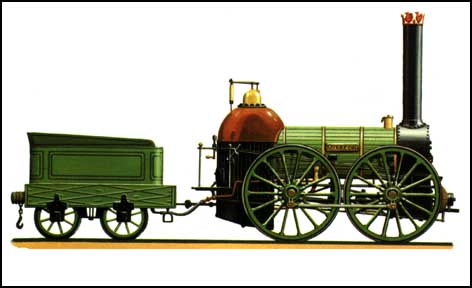

The

112½ mile line was opened throughout between London and Birmingham in September

1838 – a new rapid transport system linking the capital with the industrial

Midlands and North. It set out to

be businesslike – the trains had a uniform appearance unadorned by needless

frills. Unlike lesser lines there

were no names on engines or carriages, simple numbers sufficed; there were no

glamorous liveries; engines, carriages, staff uniforms, everything was a sober,

plain green. Bury operated this

railway efficiently and the Board had good reason to congratulate itself on its

choice of so competent an organiser.

Bury’s

contract had been framed on a train speed of 22½ mph which had seemed

reasonable in 1836, but the Post Office soon began asking for faster trains and

at Bury’s own request the contract was annulled.

From January 1839 he was employed as manager of the Locomotive Department

at a salary of £1000 as a minimum when the dividend was under 7% with an extra

£200 for each 1% above that figure. The

L&B was soon paying a 10% dividend.

The

original complement of locomotives for the main line and its 7-mile Aylesbury

Branch – 60 passenger 2-2-0 and 30 goods 0-4-0 and all to the same basic

design – was delivered by June 1841. The

earlier passenger engines had 12” x 18” cylinders, but the goods engines and

the last 22 passenger engines built from 1839 had 13” diameter cylinders.

From 1841 Bury began fitting new 13” cylinders to the older engines.

No

additions to the locomotive stock were made until 1845; from July 1844 Bury was

able to dispense entirely with the rope-worked incline between Euston and

Camden. The L&B was running

smoothly and its trains were being worked cheaply.

But

Bury’s ‘small engine’ policy was not without its critics, and some of the

directors wanted ‘big’ engines. In

1845 it was decided – for the first time – to carry coal.

In the same year the long branch to Peterborough, with hopes of a large

cattle traffic, was opened. The

board bypassed Bury and negotiated directly with Stephenson for some long-boiler

0-6-0s. 26 were obtained by

subcontracted orders from the firms of Tayleur, Longridge and Nasymth: from the

first they were a disaster. They looked much bigger than the four-wheelers but were no more powerful

than Bury’s own latest designs, were less versatile and were badly made.

In December 1846 half of them were in Wolverton for repair and others

had been sent back to the makers.

Meanwhile,

the L&B had become the southern half of the newly-formed London & North

Western Railway and engines from other sections were sent south to help out.

In November 1846 a very fed-up Bury wrote to the General Manager that he

intended to resign. Surviving correspondence shows that this came as an unwelcome

surprise to the Board; Bury worked on, and attended Locomotive Committee

meetings until March 1847. Compare

Clement Stretton’s fanciful account: ‘The L&NWR directors ordered that

Bury’s 4-wheeled engines were not to be employed on the express trains…..Mr.

Bury firmly refused to carry out the orders……24 hours settled the question.

Mr. Bury had to go’. Vivid,

but pure fiction.

In

fact, detailed records exist showing that 10-carriage trains were being

regularly worked from Euston by single 13” 2-2-0s at the end of 1847 despite

more than 60 ‘big engines’ acquired since Bury’s departure.

And despite all the stories of seven engines on one train and chronic

double-heading, two engines were only used on the heavier trains, usually of

more than 20 carriages and this was whether or not they pulled by Bury’s or

‘big’ engines.

The

(English) Great Northern Railway appointed Bury as Locomotive Superintendent in

February 1848 and the Board was sufficiently impressed by him to make him also

General Superintendent in June 1849. He

prepared the first plans for Doncaster Locomotive Works.

Bury

left the GNR in March 1850 after complaints that he was placing orders for

ironwork with firms with which he was associated.

According to the diary of R.B. Dockray of the L&NWR, Charles Fox of

Fox, Henderson & Co was ‘the presiding fiend in this….. His imagination

and malevolence will supply abundance of suspicious facts.

I shall be curious to know how so experienced and I believe really

upright a man as Bury will clear himself’.

The items in question were 25 to 30 sets of spare carriage wheels – a

minor item when Bury was then involved in seeking tenders from nine firms (none

of them Bury, Curtis & Kennedy) for 20 goods and passenger engines.

Perhaps it was a slip; perhaps he was too busy trying to get the GNR

started.

His

successor on the L&NWR was J.E. McConnell, his former fitter, at £700 a

year. McConnell (who was born at

Fermoy in 1815, of Scottish parents) is most famous for the ‘Bloomer’

singles of 1851, so successful that they ran the southern L&NW expresses

until Webb’s ‘Precedents’ took over in the late 1870s.

There is irony in the fact that the acclaimed ‘Bloomer’ design came

directly from a group of six engines delivered to the L&NWR in 1848 from

Bury, Curtis & Kennedy. Apart

from a slight overall enlargement, the main difference was that the

‘Bloomers’ were on one-piece iron plate-frames, probably because they were

built by Sharp Bros, where Charles Beyer was in control.

The rest of the design was a straight ‘lift’ from the Bury engine,

plus a fancy brass dome. The

‘Bloomer’ went on to be the basis for Webb’s ‘Precedent’ but that is

another story.

Despite

building a series of tough, capable engines, Bury’s Clarence Foundry failed,

apparently because the Russian Government defaulted on a large bill.

BC&K designed and produced most of the ironwork for a swing bridge

over the Neva in St. Petersburg. It

was opened by the Tsar in November 1850, but by that time the Clarence Foundry

has closed.

So

far from being ‘endowed richly with the commercial instinct’ as E.L. Ahrons

put it, it seems that the money-making instinct was the very thing Bury lacked. His first concern was always in running railways efficiently;

if he placed orders with his own firm it was because he could rely on his own

products. Kennedy was later to

complain that if he had only had a good commercial man as partner he would have

carried on with the Clarence Foundry.

Bury

retired to Windermere, but did not enjoy a long retirement.

He died on 25th November 1858 aged 64 and was buried at

Scarborough.

Of

the 400-plus locomotives built by Bury, Curtis & Kennedy, only two survive,

Furness Railway No. 3 ‘Old Coppernob’ in the Railway Museum at York – an

0-4-0 of 1846 – and the Great Southern & Western Railway No. 36, an

express engine with 6' diameter single driving wheels, now in the entrance hall

of Cork Station. No. 36 was built

in December 1847 and is a 5' 3” gauge version of a class built for the London

& Birmingham in the previous year. The

first thing that strikes the onlooker is how big this engine is, although

basically it is simply a Bury 2-2-0 of his original design, enlarged and with a

trailing axle. ‘Coppernob’ too,

is quite a big engine for 1846. Both

had long and busy lives and both are in practically original condition: they

were built to last.

Bury’s

legacy – from the railway workshops at Wolverton and Doncaster down to such

details as the net parcel-rack and the varnished-teak livery for carriages –

undoubtedly includes many improvements in locomotive design which have been

credited to others. A rather

reserved, cultured and speculative product of the eighteenth century, he was

unlike the generation of locomotive superintendents which succeeded him: his was

no ‘rags-to-riches’ story. The

new man at Wolverton was anxious to make his mark, denigrating his predecessor

in the process. Bury’s achievements were swept under the carpet by the new

brooms on the L&NWR. His story

was of no interest to Samuel (‘Self-help’) Smiles: it was left to his widow

to put out a short memoir. This was

ignored.

Now,

two hundred years after his birth and with the availability of railway archives

unknown to earlier writers, Edward Bury can be recognised as a great railway

organiser and one of the greatest locomotive pioneers.