WIDOW MAY PALMER AND THE SPY ON VIRGINIA AVENUE

Excerpted from Atlanta History, Summer 1997, Vol. XLI, No. 2. Footnotes are not included.

By Jamie Bisher

Long before federal agents began watching Mrs. May Palmer and steaming open her mail, she was the scandalous subject of whispers among her neighbors at 65 Virginia Avenue in Atlanta. May Palmer was a widow about 45 years old, although, as one male neighbor would point out with a wink to an interested fed, she was "very well preserved and does not look over 35." All the neighbors agreed that Mrs. Palmer was a "character." She was also the owner and landlady of the boarding house at 65 Virginia Avenue. The fact that she was a yankee who had come down from Ohio just three years before did not gain her much sympathy either.

During the night of January 31, 1917, nine nerve-racked sailors on a German freighter in Charleston harbor began a chain of events that led the feds into widow May Palmer's mailbox and personal affairs. Since the Great War began two and a half years before, Captain Johann Klattenhoff and his eight seamen had been scraping rust and fighting boredom aboard the S.S. Liebenfels. The Liebenfels was a 4,525 gross ton freighter of the Hansa Line. Like scores of other German merchantmen in U.S. ports, she had been interned where she lay at anchor when Europe sank into the bloodbath that became the First World War. The boredom ended this cold night as Captain Klattenhoff's men scurried about their ship, half-heartedly sabotaging machinery which they had long cared for and upon which their livelihoods had depended. Then they opened the seacocks to let the murky waters of the Cooper River swallow their vessel. The order to scuttle the Liebenfels had come from Berlin. The next day Berlin would announce the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, and three days later--February 4--President Woodrow Wilson would sever diplomatic relations with Germany.

Up until the time of this international commotion, Mrs. Palmer's tenants included Mr. and Mrs. George Mann, Mr. and Mrs. C.H. Annis, and Doctor Wilhelm Mueller. Mr. Mann worked at the R.O. Campbell Coal Company on Marietta Street, Mr. Annis was employed by the Sumter Telephone Supply Company, and Dr. Mueller was the Consul of the Imperial German Empire. In the days immediately following the Liebenfels sinking, Dr. Mueller was very nervous and agitated. He told Mr. Annis that he was sure that he was going to be arrested. Then Dr. Mueller vanished. He left behind most of his belongings, even his automobile. However, he apparently had the foresight to leave a note "willing" an oil portrait of himself to Mrs. Palmer.

Dr. Mueller and May Palmer had been close--close enough to start their neighbors' tongues stirring with venomous gossip. "The Doctor" gave "dinner parties, theatre parties and various entertainments" for Mrs. P. and her 17 year old daughter, Helen. Mrs. Palmer was bold enough to go "automobiling quite frequently" with Willi Mueller. She even "often [went] down to his wine cellar where they would drink wine and other liquors together." A particularly damning incident occurred when both Mrs. Palmer and Dr. Mueller coincidentally left town about the same time. Mrs. Palmer said she was going to visit friends in "a little town close to Atlanta" (probably Commerce) for a day or two. Dr. Mueller announced that he was traveling to Tennessee for two weeks. All eyebrows raised when "the Doctor" inexplicably cut short his trip and returned shortly after Mrs. Palmer. The Manns and the Annises suspected that the two libertines had rendezvoused for a passionate tryst in some discreet Georgia town.

May Palmer was not Willi Mueller's only sweetheart in Atlanta. The balding, dark-eyed diplomat with the close-trimmed mustache was a "free spender" who courted a number of ladies. Dr. Mueller treasured the good life and status that his diplomatic position afforded him, but then he probably felt that it was his just reward for years of unsavory, high risk service to the Kaiser.

For years Wilhelm Mueller had led the double life of a covert intelligence officer. Sources (probably British intelligence) alleged that in 1905 Wilhelm Mueller had somehow "assisted" the Japanese--on orders from his superiors in Berlin, of course--during the siege of Port Arthur, Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War. Several months later Mueller and an assistant were allegedly arrested in Seattle, Washington while trying to steal plans of a Royal Navy submarine in a shipyard there. Apparently Mueller and his accomplice were released, because there is no record of a trial or imprisonment. Mueller's record is blank for several years--a good credential for an intelligence officer of his era--until after he appeared in the innocuous post of German Consul in Atlanta, Georgia.

There in 1915, Mueller attracted the attention of military intelligence agents. A June, 1915 report from an agent of the U.S. Military Intelligence Division (MID) in Brunswick, Georgia declared: "Suspicious looking Teutonic characters have been inspecting [rail] cars destined for Savannah and other ports. They are reported to be in the employ of a German Agent at Atlanta [Wilhelm Mueller] where German spies are exceptionally busy." A month later, another MID report noted, "Mueller left Atlanta for Savannah, where he was expected to remain several days on business. Mueller was overheard in conversation with the Master of a German steamer. It appeared that he was going round to each Port in the District, telling the Masters of German vessels what to do under certain circumstances [i.e., in case of hostilities]." Dr. Mueller also met with German ships' captains in Wilmington, North Carolina and Charleston, South Carolina. Among the captains Mueller met was Johann Klattenhoff of the Liebenfels. It was arranged--at exactly whose suggestion is not clear--that Mueller would send correspondence to Captain Klattenhoff in care of a German-American in Charleston named Paul Wierse.

Paul Wierse was a long-time resident of Charleston, a naturalized U.S. citizen, an actuary for the Industrial Life Insurance Company, and a prominent personage in South Carolina's German expatriate community. As a good deed for transient compatriots from his old homeland, Wierse openly received and forwarded mail to interned German seamen who, of course, had no permanent addresses in the city. He also worked with the German-American Alliance to publish a small newspaper, Deutsche Zeitung. "Wierse is credited with writing most of the editorials and propaganda articles in that paper," wrote one annoyed Charleston citizen. "He showed ability as a hater of England and Kultur propagandist... Wierse foamed at the mouth almost when assaulting 'perfidious Albion'..." He irritated his fellow Charlestonians by brazenly trumpeting German innocence in the war and superiority in all fields.

Anticipating the break in diplomatic relations that would result when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, the German Foreign Ministry (in cooperation, no doubt, with the German War Ministry) passed orders through Dr. Mueller to direct interned German captains in Southeastern ports to sabotage their ships (similar orders were sent out to interned German ships in Boston and Hawaii). The main goal of this sabotage was to prevent or delay any use of these ships by the U.S.--which would certainly appropriate them for her own sudden wartime needs--in the imminent war effort against Germany. Dr. Mueller arranged for a letter to this effect to be delivered to Captain Klattenhoff via Paul Wierse in Charleston. Mueller also had given instructions to sink a ship in Savannah on the night of January 31, however this sabotage was somehow prevented.

Thus, in the first days of February, 1917, did the growing whirlwind of geopolitical struggle sweep up the lives of nine German merchant seamen and a successful German immigrant in Charleston, and an amorous landlady widow in Atlanta. Captain Klattenhoff, the crew of the Liebenfels, and Paul Wierse were soon marched off to jail. May Palmer hung Willi Mueller's portrait in her parlor and went on with her carefree life. Dr. Mueller unhappily departed the good life in Atlanta with at least one other German, "a secretary named H. Stollberg," who also had been engaged in the black arts of espionage in Georgia. Immediately after the Liebenfels incident Dr. Mueller hastily made his way to some southern port and boarded a ship for Havana, Cuba. Because Cuba was exuberantly pro-American at the time, Mueller traveled incognito. He posed as a musician on board ship, and charmed passengers with skillful renditions on his violin-cello. In Havana Mueller quickly arranged transportation aboard another steamer to Panama, again playing another reluctant violin-cello gig. Mueller called his adventurous escape "an uncommonly dangerous trip." He was in constant peril of arrest, particularly in the Panama Canal Zone where he landed on February 18. The Canal Zone functioned as a U.S. colony, and security matters there were dealt with by American police and soldiers. Luckily for Dr. Mueller, American intelligence and security organizations were still dormant, but he did not linger in the Canal Zone and dare test them.

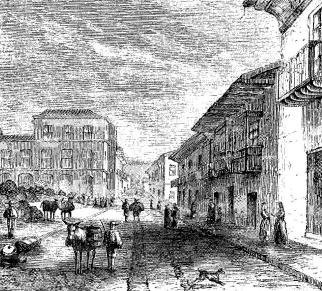

Amazingly on March 6, 1917, just over one month after departing Atlanta, Dr. Mueller miraculously arrived in the Andean city of Quito, Ecuador. Quito was a sedate, ultra-conservative little city huddling in clusters of Spanish colonial courts below towering cathedral-like mountains. The air in Quito's high altitude was so thin that a short walk along the ancient city's steep cobblestone streets made the German newcomer's heart pound and lungs thirst for thick Georgia air. "The Doctor" surely missed Atlanta, and probably wished as hard for the lady friends he left behind as he did for a rich burst of oxygen. The Government of Ecuador made things more uncomfortable for Willi Mueller. They refused to recognize him as Charge d'affaires because he lacked the usual credentials that Berlin would have been able to provide him with in peacetime. Besides, Ecuador's neutral government leaned towards the Allies and suspected Germany of covertly supporting their conniving political opposition. Mueller wrote that he felt like he was "...sitting on the powder keg all the time..." here and "...could not possibly think of letting my friends in the States know that I was still alive." Nevertheless, sometime during the next few months he would write Mr. Annis at Virginia Avenue and ask him to sell the car that he had left behind. By that time America was at war with Germany, so Mr. Annis threw Mueller's letter in his fireplace.

Meanwhile back in South Carolina, Captain Johann Klattenhoff and the eight seamen of the Liebenfels were marched into court in Florence on the first Tuesday of March, 1917. There was no delay in the trial of these saboteurs on the eve of war. Surprisingly, they were acquitted of conspiracy to sink their beloved ship, but convicted of actually sinking the vessel and received the maximum sentence--five months in a federal prison. Ironically, they were shipped off to Atlanta Penitentiary to serve their time. Captain Klattenhoff was already suffering through a more severe penance. Long before the scuttling of his cherished ship, the old captain had responded to internment like a wild bird to captivity. Johann Klattenhoff became "a very ill man mentally and physically." His mental state was so poor that he even missed his own trial, being hospitalized in Charleston at the time. He served most of his time in the Atlanta Penitentiary hospital.

On June 6, 1917, Captain Klattenhoff, Paul Wierse and Wilhelm Mueller were indicted by a federal grand jury in South Carolina of conspiracy in the sinking of the Liebenfels. Within days, the Liebenfels was rechristened as the U.S.S. Houston, and sailed off to lug men and supplies for America's war effort. "She was raised with comparative ease," noted a subsequent legal brief. "A diver was sent down to close the seacocks; she was pumped out, taken to the [Charleston] Navy Yard, and has since done valuable service for the United States as an Army Transport."

In Atlanta, the indomitable May Palmer had easily found replacement suitors for "the Doctor." In the process of selling her automobile, she became acquainted via telephone with a 35 year old Army colonel residing at the Georgian Terrace Hotel. Some suspicious allegations would later be made about how exactly she made contact with this man, however, the bottom line was that Colonel Latrobe not only liked--and bought--the car, but liked Mrs. Palmer as well, despite the fact that he was a married man.

In ensuing months, the twittering tongue of May Palmer's tenant Mrs. Mann reached the ears of Mrs. Frank C. Bither, wife of a Navy recruiter who lived on North Avenue. Mrs. Bither thought she knew sedition when she heard it, so upon hearing of May Palmer's carrying on with Herr Doctor Mueller, Mrs. Bither picked up her phone the morning of November 13, 1917, and called the Atlanta office of the U.S. Department of Justice's Bureau of Investigation (BOI--predecessor of the FBI). The BOI was very interested and dispatched Agent Stephen L. Pinckney to interview Mrs. Bither. Mrs. Bither informed Agent Pinckney that she knew both the Manns and the Annises who lived in May Palmer's boarding house, that she had heard from them how Widow Palmer and the German "were very intimate," that the spy's portrait now hung in Mrs. Palmer's apartment, and that the yankee landlady was receiving regular letters--some in secret code--from the German fugitive.

The BOI immediately opened an investigation of the carefree widow-landlady. Agent Pinckney's interview with Mrs. Bither noted that "...they [the neighbors] were afraid to get mixed up in the affair, but that they have told her, Mrs. Bither, these things and have urged her to pass the word on to the [BOI] officers." As Mrs. Annis would tell another BOI agent, "Mrs. Palmer rattled a great deal and said a great many things that were unnecessary and told all of her private affairs, in fact, all of her private affairs were public affairs." One particular event catalyzed the neighbors to send Mrs. Bither to the BOI: Mrs. Palmer received a long letter from Dr. Mueller in South America. Contained inside was a ten-page letter written in German which Mueller asked May Palmer to deliver to a Kurt Mueller. Mr. and Mrs. Annis asked Mrs. Palmer if she was really going to deliver it to Kurt Mueller. She said that she would.

The Annises were shocked. The incessant rumble of anti-German propaganda had made them vigilant patriots. In France, the American Expeditionary Force had grown to 100,000 doughboys, and, in Atlanta, signs of war mobilization--conscripts reporting to Camp Gordon, off-duty and in-transit soldiers, Liberty Loan drives--were now common sights. Although Congress had declared war on Germany more than seven months before Mrs. Bither rang up the BOI, it was not until October 23 that the American Army fired its first artillery round at German positions. On November 2, German troops raided an American trench in the Toul sector and killed three doughboys, the first of 236,000 U.S. casualties. Newspapers across America made the three dead into national heroes. Now that American boys were falling to German bullets, Mr. and Mrs. Annis asked Mrs. Bither to turn in their German-loving landlady to the BOI.

Although hardly experienced in counter-espionage investigations yet, the newborn BOI realized that Wilhelm Mueller's letter to Kurt Mueller in Atlanta might actually present a serious link to German intelligence. "Agent [Pinckney] at once had cover placed on the mail of Mrs. Palmer and Kurt Mueller at the local Post Office." In 1917, this meant that letters addressed to the suspects would be plucked from the piles of mail, steamed open, copied completely (usually manually) or inspected for any suspicious statements, resealed, and delivered. The technology was simple, and individual rights to privacy took a backseat to national security.

German intelligence did indeed pose a threat to national security. During 1915 and 1916, when the U.S. had maintained a staunch neutral stance and sentiment ran high against getting embroiled in "the European war," German intelligence operatives engaged in a violent campaign of sabotage across America. American manufacturers were eager suppliers of war material to Britain, France and Russia, and the factories that produced these lucrative supplies--uniforms, weapons, munitions, machined parts, etc.--were prime targets for German agents. It started with the bombing of the Roebling Wire and Cable plant in Trenton, New Jersey on New Years Day, 1915. By the time the U.S. declared war on Germany in April, 1917, German agents had been involved in nearly 200 destructive acts. They schemed to arm nationalists in British India using a ship chartered in California. They innoculated horses and mules bound for Europe with debilitating biological agents. They blew up the Black Tom munitions depot with a single blast that lit up the sky over New York City, shattered thousands of windows throughout Manhattan, pelted the Statue of Liberty with shrapnel, rocked the Brooklyn Bridge, caused an estimated $25 million damage, and killed several people. Section 3B of the German General Staff commanded Berlin's worldwide web of intelligence operatives. In North America, these nefarious warriors were overseen by Count Johann-Heinrich von Bernstorff, the dapper ambassador of the Imperial German Empire in Washington, DC.

Of course, the BOI did not approach and question Mrs. Palmer because she might conceivably tip off--wittingly or unwittingly--German agents or intelligence officers. The Annises moved to Kansas City in mid-November and the BOI did not interview them until the first week in December, 1917. Mrs. Annis told them about Mueller's parties with May Palmer and daughter, the oil painting Willi left for May, regular letters from Mueller "telling about the weather, his health and how he enjoyed South America, etc.," and May's forwarding letters for Mueller. Mr. Annis described May Palmer's seductive allure, then related some vaguely remembered, casual comment by her about a code Mueller had given her. The mention of a code suggested that May Palmer might be a witting agent of her German lover. Now, regardless of whether Mr. Annis' recollection was faulty, exaggerated or contrived, the BOI had to look hard at Mrs. Palmer to confirm or dismiss it.

By that time, the "mail cover" on May Palmer had turned up a number of interesting, potentially incriminating tidbits. During the first two or three days the BOI intercepted an anonymous letter--signed "Your devoted cripple"--from the Base Hospital at Fort McPherson. The army sweetheart, Colonel Latrobe, who had purchased May Palmer's car, had flipped it and been hospitalized for his injuries. Although the letter appeared to be a mere lovey-dovey mating call in ink, it caused the BOI to wonder if Widow Palmer was tantalizing the married (and blackmailable) colonel to extract military information to forward to Willi Mueller.

During the next couple of weeks, two more of Widow Palmer's lustful penpals came to the BOI's attention. One was a discreet beau named Johnson who mailed lovenotes from America, Alabama. The other was H.H. Thomas, "secretary, treasurer and general manager of the Talladega County [Alabama] Farmers' Association." Agent Pinckney dryly reported, "This man is the writer of the letters heretofore referred to being addressed 'Eve' and signed 'Adam.'" Although she was a yankee, Mrs. Palmer's peculiar fondness for east Alabama men did not arouse suspicion at the BOI.

She was a very liberated woman for Atlanta's puritanical social mores of 1917, however her liberated lifestyle did not come without a price. Mrs. Palmer's reputation suffered among her neighbors, but they were polite enough to badtalk her only behind her back and to not confront her with the ugly truth, which was that they considered her a jezebel. Someone--obviously someone close, like a neighbor--had alerted the Atlanta Police to Mrs. Palmer's extramarrital intrigues and local "vice men" had called on her recently.

On December 10, 1917, Agent Charles Reynolds visited the R.O. Campbell Coal Company on Marietta Street in Atlanta for the first BOI interview with Mr. Mann about Mrs. Palmer. At this point in the investigation the BOI wanted to avoid visiting 65 Virginia Avenue. Mann said that he and his wife had lived in Mrs. Palmer's boarding house for about a year, but felt like they did not know their landlady very well. Then Mr. Mann commenced to reveal enough details, allegations and opinions to fill a typed, two-page report. Although he and his wife shared one floor of the building with May Palmer, Mr. Mann claimed that most of his information came from the Annises, who had moved to Missouri a month before. George Mann spilled a number of details concerning May and Willi's socializing, and added something to the effect of (in Agent Reynolds' paraphrase), "She is a rather fast woman who likes to have a good time, and who cultivates the friendship of men rather than women." The basis of this latter generalization: One day Mrs. Mann knocked on May Palmer's door to invite her to a ladies get-together; Mrs. Palmer replied that she did "not care for hen parties."

Mr. Mann mentioned nothing about any code. But he knew of Mrs. Palmer's affair with Colonel Latrobe, and insisted that she "is probably criminally intimate with him." He implicated her 17 year old daughter as well, because Colonel Latrobe often brought a young soldier with him on his regular Saturday visits. An older daughter, Irene, was living in Cuba. About the time of the Mann interview, the "mail cover" revealed Irene's wise, yet belated advice to her mother about her relationship with Mueller, "You had better watch out, because the U.S. has her eyes on all enemies, Germans, Turks, Austrians and Hungarians, and they also watch the company they keep, so beware or you will be blacklisted and watched just like an enemy."

Soon after Irene's letter passed over a BOI desk in Atlanta, an American customs officer in the Panama Canal Zone "intercepted" a number of letters being transported--"outside of the regular mail"--aboard a ship of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company. Among them was a letter from C.E. Alfaro, the exiled son of the recently assassinated president of Ecuador, to a political comrade in Peru. In the letter, dated December 18, 1917, Alfaro wrote, "Give me full particulars about the farce of [Ecuador's] rupture of relations with Germany. Because I know that there still resides in Quito the secret commissioner Herr Mueller, sent from Washington by [German Ambassador and spymaster, Johann von] Bernstorff..." The U.S. Mail Censor copied Alfaro's letter and forwarded copies to military intelligence and to the State Department's Office of Counselor (State's own murky branch of spies). Alfaro's letter was sent on to its intended addressee (and the Pacific Steam Navigation Company was warned that their courier service could be a possible violation of the Trading with the Enemy Act).

U.S. intelligence operatives kept an eye on Mueller's activities in Ecuador. "He was very active in organizing [the] German Colony, and in trying to secure the adhesion of [Ecuador's] Conservative and Clerical parties to the German cause (his obvious intention being to foment a revolution against the Government of [President] Baquerizo in the hope, if successful, of securing recognition.)" MID noted that Mueller was in contact with and received operating expenses from the large, well-organized German intelligence network that emanated from Buenos Aires. Upon the death of Quito's prominent archbishop, Dr. Mueller wrote an official letter of condolence to the Vicar-General, which was "extensively published" in the press, to the dismay of Allied emissaries. "He also joined the Diplomatic Corps--uninvited--in the Funeral Procession, and took one of the seats in the Cathedral especially reserved for the duly accredited and recognized Foreign Representatives."

Suddenly the Ecuadoran Government ordered Dr. Mueller out of the country. American and English diplomats were pleased, of course, but were curious about the specific infraction that got the German booted. The trusty Mail Censors in Panama provided the convoluted answer when another fact-filled letter between Señor Alfaro and his Peruvian comrade passed through their hands. The letter described how, in the months prior to the break in U.S.-German relations in February, 1917, Ecuador's ambassador in Washington, DC had accepted money from the Germans and "even reached the point of outlining a secret treaty... with respect to the Galapagos Islands, to establish there a submarine base..." (Allegedly money had also changed hands for the Ecuadoran Government to look the other way when German agents might need to establish wireless radio stations on the country's Pacific Coast). However, Ecuador's power brokers, among whom were a number of expatriate German plantation owners, did not dare to alienate the Allies and lose the only markets--Allied and neutral countries--for their agricultural exports. So, for the benefit of the watchful eyes of Allied diplomats and spies, they went through the motions of an anti-German purge, broke off diplomatic relations and sent Dr. Mueller packing.

To Dr. Mueller, the order to get out of Ecuador surely did not seem like any kind of smokescreen. The Government of Ecuador would not even guarantee him safe passage out of the country. On December 17, 1917, he sadly loaded up a mule and plodded north out of Quito along the windswept Andean Cordillera into Columbia. Subsequent Allied intelligence reports warned that Mueller and his mule met up with two German naval officers who had fled from Chile where their warship Dresden was interned. Ridiculous rumors flew among imaginative Allied counter-espionage circles that this pathetic trio and their mules were heading to establish a secret U-boat base in Cartagena, Columbia's largest Caribbean port.

After a difficult two-month journey, Dr. Mueller arrived in Manizales, Columbia on February 19, 1918. Manizales was a lovely little, cloud-covered city astride a mountain saddle over 7,000 feet above sea level, where the interminable rainfall was enough to produce luxuriant flowers of gigantic proportions. The normal humidity was worse than Atlanta in August. "The strain and excitement affected me so that I was suddenly sickened of heart disease a few days after arriving," Mueller wrote to his mail drop in Guayaquil, Ecuador. "Sometimes, when having nocturnal attacks, I doubt whether I will ever leave Columbia... What is to become of me in these sad circumstances, heaven knows." Dr. Mueller advised his Guayaquil mail drop of his new mail drop's address in Bogota and then, perhaps in a moment of self-pity, complained that he--Mueller--had little enthusiasm for a pay-raise offered him--"No one will take my checks..."

The Doctor's German friend in Atlanta, Kurt Mueller (no relation), was enduring a different kind of difficulty. Ever since the BOI had gotten wind of Consul Mueller's ten-page letter to Kurt Mueller several weeks before, the Atlanta resident "and his wife were constantly under observation." They would be under surveillance for about the first six months of 1918 before the Department of Justice decided that they "had shown no tendency to engage in pro-German activities or express anti-American sentiments." Meanwhile, their reputations and relationships with their fellow Atlantans surely suffered immensely, as might be imagined when someone is constantly tailed by federal agents. Regardless of the fact that the BOI determined that Mr. and Mrs. Kurt Mueller were not spies, the couple still came dangerously close to being interned for the duration of the war as "alien enemies." Their innocent receiving of Dr. Mueller's letter apparently put them in "violation of Section 3(c) of the Trading with the Enemy Act."

In addition to the BOI, M.I.4, the military intelligence section responsible for Counter-Espionage Among the Civilian Population, was investigating Mueller's Georgia connections. A February 2, 1918 letter from M.I.4 to the Chief of the BOI stated, "Mueller is the kind of spy who takes advantage of women, most of the information he receives coming from them. All women who have been in touch with him (in Atlanta) are being closely watched." The mail cover on May Palmer continued to produce anonymous letters full of lust and whispers of secret rendezvous, but no military secrets.

Dr. Wilhelm Mueller was sick and tired of intrigue and life on the run. He announced this, best he could, when he wrote an amiable letter of instructions to his Guayaquil mail drop on March 1, 1918. Obviously anticipating Allied mail censors to pore over his words, Mueller's letter declared, "Let some one else understand this--I don't want anything but to live here quietly...!"

The wake of the Liebenfels sinking had still not subsided back in the U.S. Paul Wierse's lawyer appealed his case all the way to the Supreme Court in Washington, where his petition was finally denied in October, 1918. Wierse, unlike the captain and crew of the Liebenfels, had so far avoided serving any of his two year sentence and remained free on bail, thanks to his aggressive legal counsel. Even though his sons were serving in the U.S. Army, many Charlestonians and some Justice Department officials were clamoring for Wierse to be stripped of his American citizenship. Wierse's only crime had been to pass on Consul Mueller's nefarious instructions to Captain Klattenhoff, instructions which were probably not even known to Wierse. Nevertheless, Wierse's public tirades on behalf of his beloved Kaiser had long before dyed him as a traitor who put loyalty to Germany above his allegiance to the United States.

Sometime in late September or October, 1918, a US military intelligence agent passing through the Columbian Andes near Manizales came across clues that suggested a secluded German wireless outpost high in the mountains. The agent was Charles Waite, a middle-aged travelling salesman for a St. Louis stationary company with much experience in rural Columbia. Waite set out through the mountains on horseback to the suspected location of the German wireless outpost. In his pocket was a photograph of the dangerous German spy Wilhelm Mueller, given him by the U.S. Army Intelligence Office at Ancon, Canal Zone weeks before. On a narrow mountain trail, another rider suddenly emerged from the fog. Waite was electrified with fear--the man looked just like the photograph. Waite did nothing, but his horse was wise enough to take the inside of the shoestring trail. The horses bumped as they passed, and suddenly the German and his mount plunged hundreds of feet into the canyon below.

For several months the State Department and the Military Intelligence Division sought in vain to confirm whether Mueller was in fact the corpse at the bottom of the remote Columbia cliff. An armistice ended the World War on November 11, 1918, but the search to bring German saboteurs to justice continued. In January, 1919, a German travelling under an alias through Panama was apprehended and believed to be Dr. Mueller. The BOI rushed a photograph of May Palmer's oil painting of Mueller down to Panama. They had the wrong man. Likewise, the unfortunate fellow pushed over the Columbian precipice by Charles Waite's horse turned out to be innocent as well.

In mid-summer, 1919, U.S. agents intercepted a letter from the elusive Dr. Mueller. He had been living quietly among small German communities in Venezuela for a year. On June 22 he wrote an old flame in Charleston, a widow with two children, and proposed marriage to her. Messages flew back and forth between the BOI, Military Intelligence Division, State Department and the U.S. Military Attache in Venezuela. All of the American counter-espionage sleuths were sure that Mueller could easily be lured back to the U.S. by romance. "If you want this bird," wrote one official to the State Department, "he is yours for the asking."

Inexplicably, the American counter-espionage establishment's passion for capturing Dr. Mueller waned just as he came into reach. After putting so much energy into the hunt for Mueller, the American bureaucrats and colonels just seemed to have lost interest. Just as May Palmer replaced Willi Mueller, seemingly without a second thought, the counter-spies in Washington dropped Mueller and began pursuing Bolsheviks and other sundry Reds.

Widow May Palmer's escapades with the German spymaster were remembered only by her rumor-mongering tenants. On August 20, 1935, the U.S. Attorney General dismissed the indictment against Dr. Wilhelm Mueller for conspiracy to sink the Liebenfels.

END