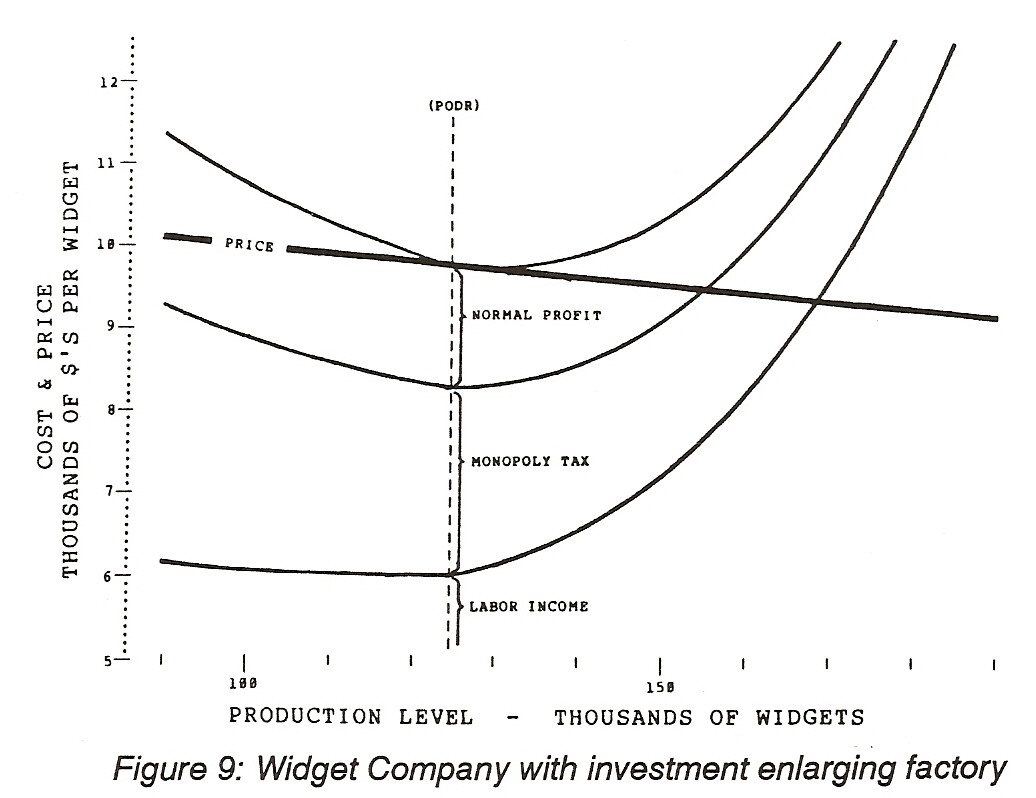

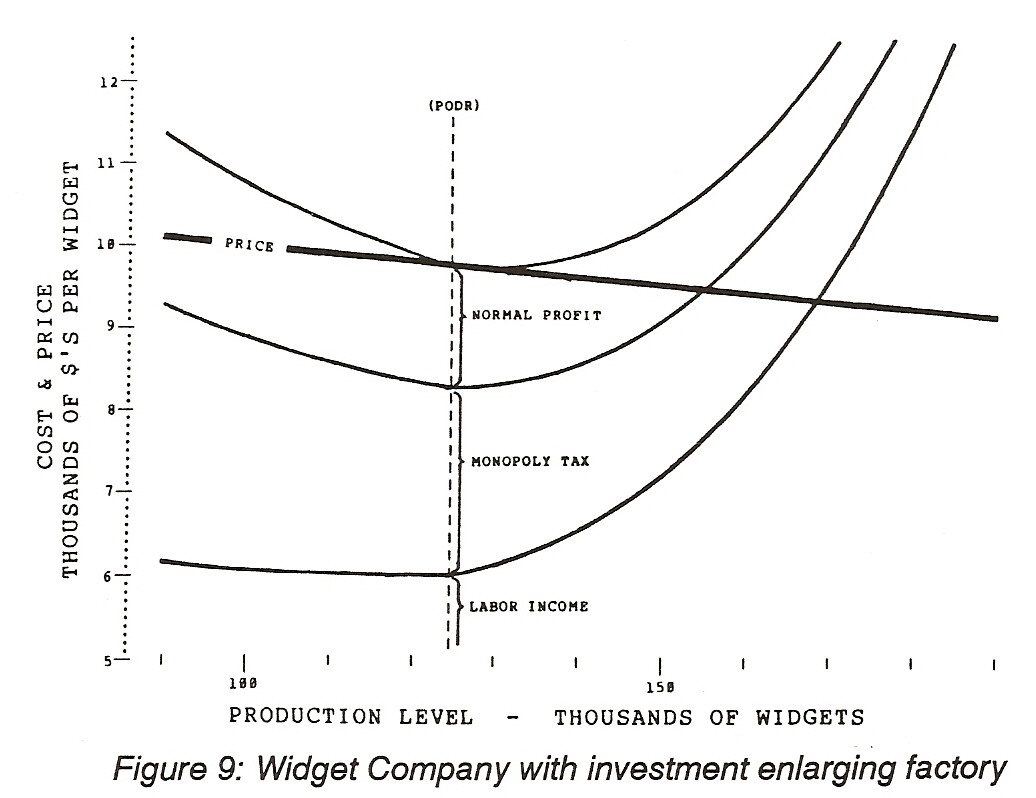

Now that economic interest is recognized as normal profit, the remainder of this analysis will refer to this cost as normal profit and any time the analysis shows that a monopoly profit (or loss) occurs the monopoly tax will be adjusted to make monopoly profit zero. This is how the empirical method used to demonstrate the monopoly tax works.

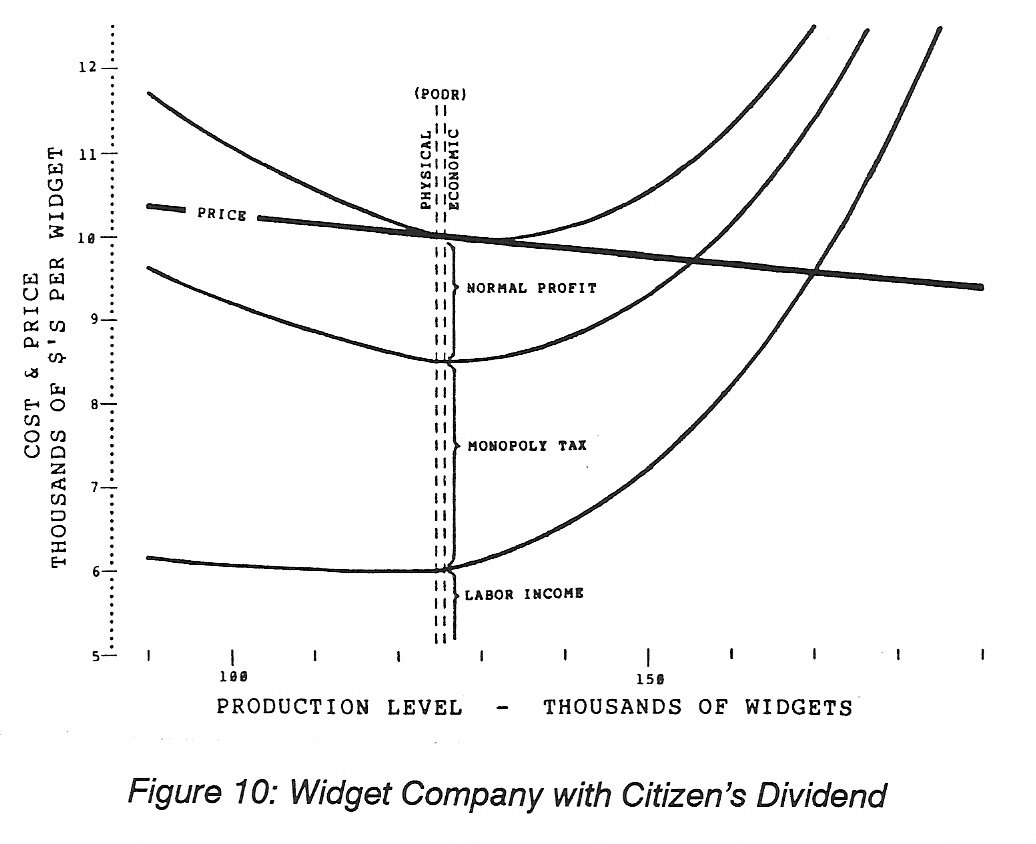

Another confusion arises from the meaning of the point of diminishing returns. As was stated earlier, economists explain this phenomenon on the basis of the proportions of labor and capital as was done here. However, in their presentations of the supply-demand schedules they also refer to the point of maximum profit as the point of diminishing returns. This is because above or below the point of maximum profit any change in production level results in less profit, not more. That is, it is the economic point of diminishing returns. The other is the physical point of diminishing returns. It seems inexcusable that this distinction is not made by economists but they do not make it.

The reason this distinction is important is because to make the most profit the two points must be the same. Too much capital results in capital being left idle and wasting, too much labor results in inefficient production. It is to bring these two points into agreement that is the motive for investment. That is, to reduce costs of production more capital is invested, normal profit increases and the cost of labor per unit of production is reduced.

However, this only happens when maximum profit occurs at a production level above the physical point of diminishing returns. If production is below this point further investment makes no sense, excess capital is already being wasted. By shifting the tax burden from labor and profits to monopoly (ownership/control) the economic point of diminishing returns is moved above the physical point of diminishing returns and makes investment a rational decision.

Increasing factory size to efficiently produce 104,000 widgets -- the economic point of diminishing returns -- causes unit labor costs to be reduced and normal profits to be increased to compensate for the additional investment. When the costs are analyzed for this larger factory it is found that not only do normal profits increase but so do monopoly profits and the economic point of diminishing returns. This calls for another round of investment.

In fact, this condition results several more times and by the

time the two points become equal the factory expansion reaches 124,500

widgets, labor income becomes $747,000,000; taxes are $252,033,000; and

normal profits have reached $186,750,000. Monopoly profits have increased

to $29,058,000. However, as was said earlier, whenever monopoly profits

are not zero the monopoly tax is adjusted to make them zero. The complete

supply-demand schedules for this larger factory are shown in Figure

9.

By the simple expedient of changing the form of taxes we have now moved the company forward so that widget production, labor income, normal profit and tax collections have all increased by nearly 25%. In addition to this the price of widgets has been reduced to $9,757.56 Truly a win-win-win situation. But, there is one more consideration to examine. That condition is the Citizen Dividend. Monopoly profit, however, has been reduced. But that is why it is called a monopoly tax and since the monopoly profit is a result of the monopoly privilege granted by society -- Why shouldn't the society benefit by collecting some of this profit to finance government and share with the society that creates the value?

Widgets are selected by economists to show the cause-effect relationships of producing anything and everything. They do this because to show these relationships for a non-descript product like widgets makes it clear that the only difference between a widget factory and the economy as a whole is the size of the factory. Our $5,000,000,000,000 (five trillion dollar) economy

With this in mind, it is obvious the reduced price of widgets necessary to cause people to buy more widgets represents an increase in the value of the dollar. That is, it causes deflation. In Step 1, A Stable Currency it was shown that monetary policy should be used to maintain a constant value of money. That monetary policy depends on the Federal Reserve System buying government bonds to counteract deflation. But, here we have the government collecting more taxes and that, of course, will eventually pay off the National Debt leaving no government bonds for the Federal Reserve System to buy. It also raises the question - What is the government to do with all the revenue it can not spend even imprudently? What to do?

One way to handle this problem would be to allow the owners of widget factories to keep some monopoly profits as they do now and let it go at that. However, because it is removal of the productive restraints of monopoly that causes economic growth in the first place [Or, if Don Dale is right in his assessment that this is merely a non-distortionary tax and not a cause of economic growth, it provides the funds that allow a reduction in variable costs of production which unquestionably does cause grwth -- see below.] such an action will not only reduce the problem of excess government revenue it will also reduce economic growth. Perhaps we should look to the source of this revenue and return it to the cause. That only seems fair. But, does mother nature want it?

Many will disagree that mother nature produces this excess and claim it belongs to the investors who risked their wealth guessing that their large factory will be able to sell all it produces. It is, after all, the economies of scale that are the motive for investment and the economies of scale cause the lowering of prices. But, do the factory owners really cause the economies of scale? Are not the people who are the marketplace just as much the cause of these economies? Can large factories be efficient producers if there are no people to buy their products?

Henry George made a similar observation that led him to write his famous treatise Progress and Poverty. His observations were made concerning the value of land that is created by increasing population but is claimed by land monopolists. The only difference here is that the monopolists are claiming the value of the economies of scale created by the economic viability of the society. The source of the value created is as much mother nature in the one case as the other. People are part of nature. It is the swelling demands of increased population that increase the economic value of land. It is the swelling demands of population that create the economic value of mass production.

The truth is, there is no way to determine who is the rightful claimant to the value produced by nature or, if you prefer, produced by society as a whole. But, we can examine the distribution of this value for its effects on production. That is, we can grant the revenue as a Citizen's Dividend and examine its effects on production.

There are not many causes of demand -- the quantity of widgets bought and sold for a given price -- that are more certain than the relationship that an increase in peoples purchasing power will increase the quantity of things they are willing and able to buy at any given price. By giving people the revenue necessary to pay $10,000 per widget no matter how many widgets they buy we solve the problem of deflation caused by the growth caused by the monopoly tax. We do not know how much of a dividend this will be but, for now, we will simply say it is enough to do the job.

The Citizen Dividend does not, of course, change the relationship

of price changes to demand changes. That is, there is still a 250 widget

change in demand for each 0.025% change in price. What does change is the

number of widgets priced at $10,000 (or any other price) that are bought

and sold. To avoid deflation, the Citizen's Dividend will be made sufficient

to cause the demand at $10,000 to be the same as demand of our expanded

widget factory - 124,500 widgets. The effect this has on production and

price is shown in Figure 10.

The Citizen's Dividend causes the economic point of diminishing returns -- the point of maximum profit -- to increase to 125,500 widgets with all the associated increases in labor income, and government revenue.

The increase in the point of diminishing economic returns, of

course, calls for additional investment and, like the previous investment

example this, too, causes the economic point of diminishing returns to

move further above the physical point of diminishing returns which, in

turn, causes the price to fall and requires an increase in the Citizen's

Dividend. However, like all natural phenomenon, this process does have

its limits. The limit of expansion for our model widget factory is shown

in Figure 11.

The ultimate point is reached with production raised to 131,500 widgets, labor income increases to $789,000,000 government taxes increase to $328,751,000 and normal profits increase to $197,250,000. An even better win-win-win situation than without the Citizen's Dividend.

Table 3 shows the summary of production, price and labor distribution changes for each of the iterations taken along our road to economic freedom.

Next in the Epilogue - From Here to There we will examine each of the three steps to discover a practical way of getting from our present circumstances of unstable currency, stifling taxes and a demeaning welfare bureaucracy to a freedom to pursue happiness and ensure our right to receive a fair share of the produce of nature. Along the way we will also learn a few things about the limits of production.

But, first, here is a summary of the measures, goals and controls for the Three Steps to Economic Freedom along with the assumptions that must be true if these controls are to work.

Most notable here is the difference between this program and the

typical economist's proposals. First comes a usable measure to define success

or failure of the actions taken; then comes a statement of what is a favorable

outcome; then there is the method by which one responds to the measured

outcome; and, finally, there is the minimum assuptions neccessary to be

believed for the methods to be valid. Can any other economic proposal meet

these essential characteristics of a rational empirical feedback of proposed

actions? See Table IV -- Measures, Goals,

Controls and Assumptions.

Return to Contents Page

Return to Home Page