STEP 2

TAXING MONOPOLY

There are few, if any, rules of understanding superior to Ockham's Razor:

What can be done with fewer assumptions is done in vain with

more.

William of Ockham (1280-1348)

Economists, it seems, prefer to ignore the wisdom of this simplicity and pursue their "science" with the compilation of all the extraneous observations they can find. However, when one puts aside the verbal nonsense of these pseudo-scientists and analyses economics in the light of Ockham's Razor, the problems of this dismal enterprise can be understood and controlled.

Economics involves study of things having exchange value. Tautologically, exchange value is a subset of value. Therefore, exchange value must, at minimum, be value. While it presents an interesting question: "Why or how does value come to be?" It is irrelevant to the study of economics. For this purpose it is sufficient to accept that value does exist (our first assumption) and concern ourselves only with the question: "What makes value become exchange value?"

The answer to this question is simply -- monopoly.

Exchange value is value that is monopolized. It is value that is not free. It must be paid for or taken by force.

Monopoly is one of the economic concepts that have been unnecessarily complicated by economists' penchant to ignore the wisdom of Ockham's Razor. They define it with an assemblage of extraneous and ambiguous conditions that obfuscate its meaning. The meaning of monopoly is completely understood by anyone who has ever uttered the words -- "He has monopolized my

time" -- or any similar such sentiment. The meaning (our second assumption) is clear -- monopoly is control of something by force or agreement. It can only be exchanged by paying a price or by an opposing force. No other conditions or assumptions are needed to understand this meaning of monopoly. Understanding this meaning opens the door to the essence of economics -- The Equation of Exchange Value. The equation is based on obvious observations conditioned only on these two assumptions.

The first such observation is that the total of exchange value

- E - is equal to the sum of all, from the first (m=1) to the last (m=M), of the subsets of exchange value E-sub-m.

That is:

E = SUM(from m = 1 to M) of E-sub-m

A few compromises have been made here to accommodate my ignorance of HTMLcoding. "SUM" has been substituted for the more conventional greek capital sigma; "from ... to ..." has been substituted for the conventional abbreviation meaning exactly that; and, "E-sub-m" has been substituted for the usual subscript that is read as "sub" so nothing much other than brevity is lost in the translation.

The subsets of exchange value are the average prices of various items - bread, shirts, corporations, franchise licenses, etc. - times the total quantity of those items. The sum of all these subsets of exchange value is a measure of the total of all exchange value.

[Note: The difference between price and exchange value is relevant. It will be discussed later. -- jbod]

Although our curiosity may be aroused by a measure of the total exchange value of everything that is, this measure is not our usual purpose for economic analysis. Our purpose is more likely to be to learn how to control changes in the amount or distribution of exchange value. To do this we must examine changes in exchange value. The conventional expression

for change is the greek letter delta placed before the thing undergoing change. To again overcome my deficiencies in HTML I will substitute the letter "D" for delta. This is D(E) for changes in total exchange value and D(E-sub-m) for changes in each subset of exchange value.

We are also concerned with the time it takes for these changes. That is, it does make a difference if the changes occur over a millennium rather than a month. Expressing the rate of change requires that we divide the change in value by the period of time [D(t)] it takes for the changes to occur. This is written as:

[D(E)]/[D(t)] = SUM(from m = 1 to M){[D(E-sub-m)]/[D(t)]}

The next observation is that if changes in exchange value are

to be controlled then there must be a control. For a control

to be effective it must cause a recognizable effect on the

thing we are trying to control. If we are to obtain the result we want we must also be able to relate the changes we cause

to the change in the thing controlled.

The possible candidates for controls, let us call them

X-sub-n's,

are everything we believe causes an economic effect. Our task is

to find among all the possible controls those that are, in fact not merely belief, effective in causing the

changes we desire.

Effective control is found by relating the change we desire

D(E-sub-m)

with a change we cause

D(X-sub-n),

and multiplying that cause-effect relationship by the rate

of change

{D(X-sub-n)}/{D(t)},

we cause in the control. Entering this observation into our earlier equation we have the

Equation of Exchange Value:

D(E)/D(t) =

SUM(m = 1 to M) SUM(n = 1 to N) {[D(E-sub-m)/D(X-sub-n)] times [D(X-sub-n)/D(t)]},

To this point, these observations have been entirely tautological. That is, they have been presented in mathematical form and are true by definition. To make use of this degree of certainty we must be able to identify our erroneous beliefs about cause and effect and replace them with our discoveries of the reality of nature. There are several ways to do this.

We can measure changes in both the result we want

{D(E-sub-m)}/{D(t)},

and the thing

{D(X-sub-n)}/{D(t)},

we believe causes that result. We can then assume our belief is true and proceed on that basis until we are faced with evidence that shows our belief to be false. This method depends on a long history of observations as was done in the days of alchemy and continues today in the practice of astrology, economics and other belief systems that base their premises on reason rather than revelation. This method of discovery is called empiricism.

Empiricism has led to many useful discoveries. It can even be credited with being the basis of all discoveries by the enlightened methodology of science. Little of our understanding about how things work has ever been discovered without someone first observing a correlation between events and then assuming that one thing causes another.

Among all the things we believe control the things we want, there are some that allow us to demonstrate and measure that a change we cause does result in the change we desire. These are the controls which are either themselves the things we wish to change or they are directly and irrefutably related to the things we wish to control.

Attempting to present an example of the first group -- the control is the end -- would only raise a semantic digression into the philosophical exercise of debating if a word describes a thing that is itself relevant or merely an attribute of something else. It is the second group, those things that are irrefutably related, that will be argued in this discussion.

This second group can be divided into two types. The first type is based on observation that is so obvious and intuitive that we have no reason to doubt it is so. The second type is based on tautological relationships.

An example of the first type is our understanding that when a lighted match is set to fuel, it is the lighted match that causes the fuel to catch fire. So long as this happens we will continue to believe the one causes the other.

The second type requires us to make use of an existing tautological relationship or create one. It is this type that permits us to examine the truth of our beliefs.

If the thing we wish to control is a particular subset of economic value -- E-sub-m. -- we can create a link between it and our proposed control -- C. We can measure the product of the control and the desired effect -- C times E-sub-m -- and with this link discover if the proposed control is directly, inversely or irrelevantly related to the subset of economic value we are trying to control.

Before we proceed with how this is done, we will first make some observations that deal with the three possibile outcomes just stated.

If the effect of the proposed control is directly related to E-sub-m then increases in the control will cause increases in E-sub-m and decreases will cause decreases. If the effect of the control is inversely related then an increase in C will result in a decrease in E-sub-m and vice-versa. If a control is irrelevant, no such relationship exists.

The next observation is that most things in nature follow a parabolic growth pattern. That is, things tend to grow initially at a rapid rate, then slower and finally they enter a state of decline.

In economics this phenomenon is the basis for such theories as marginal efficiency, economic indifference, economies of scale, etc. Most of these theories present the parabolic growth pattern with a different order derivative [That's calculus talk meaning an underlying rate of change like distance to velocity {v = d(s)/d(t)} to acceleration {a = d(v)/d(t)} , etc., much like our D(E)/D(t),

etc.] than is used to demonstrate the relationship itself.

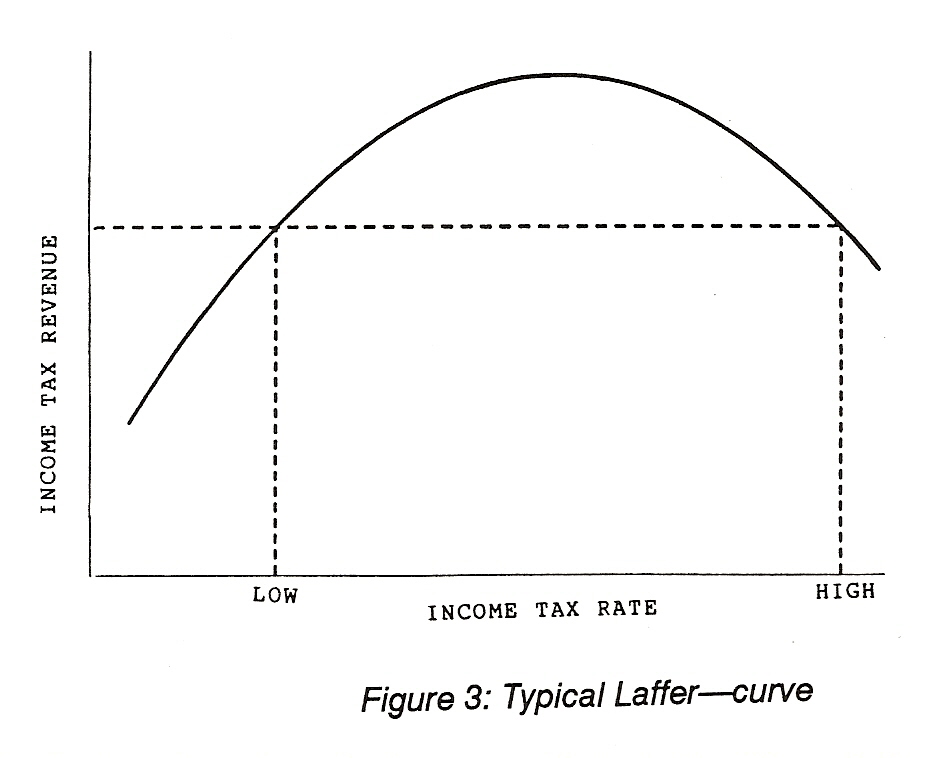

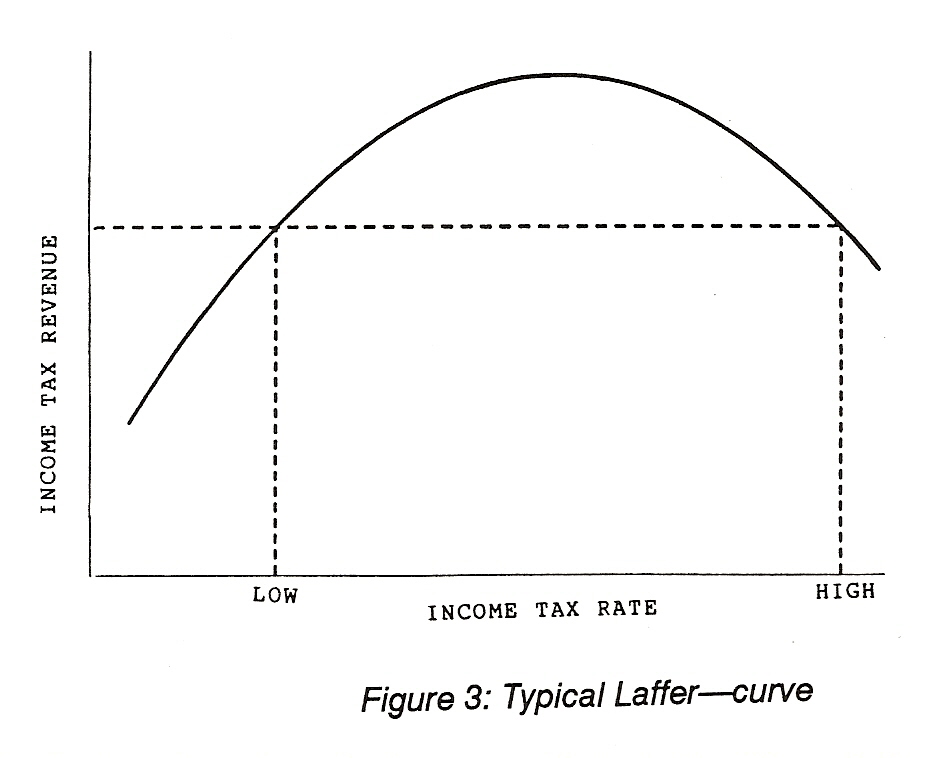

However, there is an economic argument that is based directly on this parabolic growth curve. This argument is the recently popular income tax "Laffer-curve" shown here as Figure 3.

The Laffer-curve shows that income tax revenue can sometimes be increased by increases in tax rates and other times by decreases. The curve is shown to be true by analysis of the obvious relationship between tax rates and tax revenue.

The Laffer-curve shows that income tax revenue can sometimes be increased by increases in tax rates and other times by decreases. The curve is shown to be true by analysis of the obvious relationship between tax rates and tax revenue.

The extremes of the curve are the first conditions to examine.

If the tax rate is zero there will be no tax revenue. If the rate is 100 percent its effect is confiscation and no one will produce anything for the purpose of confiscation. Again, there will be no tax revenue.

Any tax rate between these two extremes will produce some revenue and, except for the point of maximum revenue, there are two tax rates for each level of revenue. One lies above the optimum rate and one below. The higher rate is nearer to confiscation and does great harm to production. The lower one is nearer to free trade and does less harm to production.

There is no question as to which is the better choice. The only

serious question is - "Where are we on the Laffer-curve?" The arguments that follow could be used to resolve this question but, in fact, there is a better use.

The Laffer-curve shows that income tax rates can sometimes be

lowered and produce greater revenue while doing less harm to the economy. The arguments that follow reveal an even more startling truth. This truth has its roots in the economic analysis of the phsyiocrats of Adam Smith's time, it is inherent in the freedom-inspired writings of founding patriot Thomas Paine, and it is the basis of the economic analysis in Henry George's

Progress and Poverty. This truth is that monopoly taxes can cause growth in economic value. A corollary we will call a Citizen's Dividend shows the same effect.

[Note:

A criticism from Don Dale of Princeton University said

that it is the reduction of the "variable cost taxes" I use to

replace the "fixed cost taxes" in my analysis that is the cause

of the economic growth from implementing my tax scheme. He

used the term "non-distortionary tax" to describe what I call a

fixed cost tax. This is not an accurate description of my proposed

tax system. The non-distortionary taxes he refers to are not "fixed

cost taxes" but are taxes like corporate profit taxes that are

neutral in the fixed-cost variable-cost spectrum.

I have not completely ruled out the possibility that fixed cost

taxes can actually cause economic growth as suggested by Don

Dale, but, because government will collect taxes in any case, even

a change to non-distortionary taxes like corporate profit taxes

from taxes that resolve to variable costs of production like sales

and personal income taxes shows such an obvious benefit to

economic growth it seems like another of those foolishnesses of

economists to look for answers in all the wrong places while

ignoring those with substantial benefits that lie right under

their collective noses. However, because of the possibility that

the tax program I propose in my analysis may not behave quite

as beneficially as I originally claimed, I have changed my

proposal slightly to correct for this possibility by replacing the

do-nothing neutral position with a minimal increase in the tax.

Should a re-examination of my proposal show that there actually

is a positive consequence to an increase in the fixed cost tax, I

will reinstate the neutral condition. -- jbod]

To proceed with these arguments, we will first examine the difference between "price" and "economic value" that was mentioned earlier. The difference between price and economic value is that a seller's valuation of the thing sold is always less than the transaction price and a buyer's valuation

is always greater than the price paid. Without this difference exchanges would not take place.

With this difference things of economic value move from those who hold them in lesser value to those who will hold them in greater value. Each such exchange causes an increase in economic value because the buyer gives money considered of less value

than the thing bought and the seller receives money considered of greater value than the thing sold. However, a problem with this process is the problem of abuse of the cause of economic value. The condition of monopoly.

Having a monopoly means one is privileged to establish whatever

price one chooses. If the price is set significantly above prevailing economic value exchange will not occur. For all the time this condition exists exchange does not occur and, therefore, does not cause an increase in economic value.

The problem of a price set above economic value is speculation.

A monopolist can withhold things owned -- cars, clothes, land,

etc. -- until forced by necessity to sell at the prevailing economic value or until someone is desperate enough to pay the speculative price. Circumstances that are faced more often by the poor than the propertied. To overcome this abuse of monopoly it is necessary to impose a price on monopoly privilege. That price is a tax. The taxes should be applied to offered for sale prices of relevant things so prices are forced down to economic value. The remaining issues are to determine which prices are relevant

and how to optimize the taxes.

Relevance in this instance refers to possibilities of abuse of

the monopoly privilege of price setting. Where there is substantial competition -- family farms, mom and pop stores, private homes of reasonable value, etc. -- there can be no price speculation to impede progression to greater economic value. However, where there is substantial possibility of speculative

gain -- such as withholding of land as described by Henry George in his masterpiece Progress and Poverty; large concentrations of ownership that exploit the economies of scale made possible by an economically viable society; and, licenses granted by society for utility and broadcast franchises and the freedom to do business with limited liability -- then the price setting privilege is relevant.

The method to determine the price relevance of a particular subset of economic value is to proceed with the application of the tax program to those cases that appear most likely to be relevant. The optimum tax is then determined by the Equation of Exchange Value.

Tax rates will proceed towards the optimum and, for items not relevant, tax revenue will be so low as to be obviously unnecessary. These characteristics can best be shown by example.

As an example I will use a subset of economic value that obviously has potential for abuse. These are corporations that control in excess of 100 million dollars of assets. Even the most obstinate can see these are relevant in the sense just described.

The process starts by applying a tax to the assets of these corporations. The measure of assets is the same as is used to tax residential property people hold to sustain their Constitutionally secured right to life. It is the sum of all the debt owed by the corporation -- i.e., the mortgage -- plus the equity values established by the price of its common stock.

Politicians, lawyers and some economists will undoubtedly object

to this taxation of "capital." But, when one considers that this tax base is the same as is used to tax people for the right to own a home, it seems inconceivable that those who exercise the government granted privilege of limited liability (the real meaning of incorporation) should not be asked to pay for this privilege!

To initialize the process a tax of $10 per month for each one

million dollars of assets in excess of 100 million dollars plus $10 per month for each one million dollars of assets in excess of 200 million dollars, etc. continuing up in 100 million dollar increments through the total amount of corporate assets. This tax is then collected for a two month period. The tax rates are then increased to $10.02 and collected for another two months. This gives us the data required to determine if the tax rates should be increased, decreased or be unchanged. The decisions are based on the obvious relationships of the Equation of Exchange Value.

The tax revenues obviously:

(a) Are tautologically related to the exchange value

of each of the tax increments.

That is, because the tax receipts are a fraction of the exchange value, then the tax rates are the equivalent of the control -- C -- and each increment of the tax base is like the subsets of economic value described earlier:

Tax Revenue = C*E-sub-m

Where;

C = the Tax Rate; and,

E-sub-m = the Tax Base

(b) Because of this tautological relationship, growth

of each subset of economic value is the same as

the growth of each subset of tax revenues so long

as the tax rate is not changed.

(c) The growth rate of economic value and tax revenue

with the second tax rate can only be greater than,

less than or the same as with the first tax rate.

(d) Any difference between the growth rates of the

periods can

only be because of the change in the

tax rates or because of something else.

With these observations we can proceed to optimize the tax rates. This process is:

(1) If the change in the growth rate

of tax revenue is

less with the second tax rate than with the first

then change the tax rate half the amount of the

prior change and in the opposite direction of the

prior change.

That is, if the first tax rate was $10.00 and the second was $10.02 then lower the tax rate to $10.01. If the first tax rate was $10.02 and the second was $10.00 raise the tax rate to $10.01.

(2) If the growth rate of tax revenue is greater with

the second tax rate than it was with the first then

change the tax rate by twice the amount and in the

same direction as the prior change.

(3) If there was no change in the growth rate of tax

revenue then increase the tax rate by $0.01.

[NOTE: This is the change from my previous

"do nothing" choice because of Don Dale's

comments. -- jbod]

(4) Repeat the process for each two month

period and each increment

of economic value.

Because of the tautological relationship between tax revenue and economic value, any change in growth rates caused by the tax will follow a consistent pattern similar to the Laffer-curve. That is, if the relationship is direct, tax rates will increase towards the optimum rate. If the

relationship is inverse then the rates will decline towards the optimum. When no change results tax rates are either optimum or irrelevant. If the optimum rate produces insufficient revenue to justify the expense of collecting the tax, the rate should obviously be considered irrelevant and be reduced to zero.

Because any change in growth of tax revenues not caused by the tax are tautologically unrelated to changes in the tax rates, these changes will be random with respect to changes in the tax rates. They will, therefore, have only transitory effects on the optimization process.

Undoubtedly there will be many objections to this analysis. I

cannot perceive of nor find time or space to refute all these arguments. So, instead, I will address the corollary that those who find the tax program is "too good to be true" will find as unbelievable as Alice's trip Through the Looking Glass.

One of the more interesting facets of this tax program is that because it causes increases in economic value, any inappropriate lowering of taxes will cause a reduction in economic growth. This is true even when our profligate government cannot reasonably spend all revenue collected. Although this "problem" may appear to be a version of Alice in Wonderland, it is also an obvious outcome when one considers the meaning of optimum.

[Note: This effect is also true of the program regardless

of whether or not the fixed-cost tax causes economic

growth or merely removes the burden of economic

restraint caused by variable cost taxes as described

by Don Dale. -- jbod]

When fully implemented and optimized, the revenue collected with this program will be growing at the maximum rate possible in an economy that is also growing at its maximum possible rate. All other government intervention into economic decisions will reduce the rate of economic growth. While some taxes may be justifiably implemented for non-economic political reasons, these actions will inevitably cost slower economic

growth because they prevent optimization by the Equation of Exchange Value. When all is said and done, this program works because it causes prices to be forced toward economic value and thereby erases the advantage of individual monopoly price setting privilege. As was said

by Henry George --

"But the great class of taxes from which revenue may

be derived without interference with production are

taxes upon monopolies -- for the profit of monopoly

is in itself a tax levied upon production, and to tax

it is simply to divert into the public coffers what

production must in any event pay."

it is and always has been abuse of monopoly that hinders economic growth.

To add further disbelief to this seeming fairy-tale, consider

what would happen if the excess revenue is distributed to the people. Aside from raising objections from self-righteous purveyors of arrogant ignorance who insist they know what they in fact only believe, the "Citizen's Dividend" will both ease the plight of the impoverished and cause the economy to grow by the demand created from this sharing of the produce of nature and society in general. Keynes' cans of money proposal may not be so ludicrous, after all.

A demonstration that this tax on monopoly will cause an increase in economic activity is included with the development of the Widgets in S-Basic model used to introduce the corrolary "Citizen's Dividend" in the next chapter.

Comments or discussion of any of these articles or related material is invited.

[email protected]

Return to Contents Page

Return to Home Page

The Laffer-curve shows that income tax revenue can sometimes be increased by increases in tax rates and other times by decreases. The curve is shown to be true by analysis of the obvious relationship between tax rates and tax revenue.

The Laffer-curve shows that income tax revenue can sometimes be increased by increases in tax rates and other times by decreases. The curve is shown to be true by analysis of the obvious relationship between tax rates and tax revenue.