Etruscan ritual text on linen mummy binds in Zagreb

Etruscan ritual text on linen mummy binds in ZagrebThe Liber Linteus

Etruscan ritual text on linen mummy binds in Zagreb

Etruscan ritual text on linen mummy binds in Zagreb

This page reviews what is now known of the Liber Linteus of Zagreb. I would like to express my gratitude to the source of the information provided here, prof.dr. R.S.P. Beekes and dr. L.B. van der Meer who are both connected with the University of Leiden, The Netherlands, and whose student I have been. The review of the Etruscan Grammar is, in fact, a translation from the Dutch language of a part of Chapter 4 of the book "De Etrusken Spreken" by R.S.P. Beekes and L.B. van der Meer (Coutinho, Muiderberg 1991).

Introduction

In 1848 or 1849, a nobleman from Slovenia, Mihail de Baric, bought a mummy in Egypt, which found its way into the National Museum of Zagreb in 1862. Where the mummy had been found and sold is unknown. The mummy consisted of the remains of a child. It was wrapped in a piece of linen cloth, which had been torn into wrapping binds. The linen cloth had been written on with texts in ink, apparently before it was torn into pieces and used as mummy wrapping.

At first it was thought that the texts were a literal transcription from a text in Egyptian. Only in 1891, the Austrian egyptologist J.Krall discovered, that the Liber Linteus(a linen book) consisted of an Etruscan text, the longest Etruscan text known to us today (approx. 1200 words).

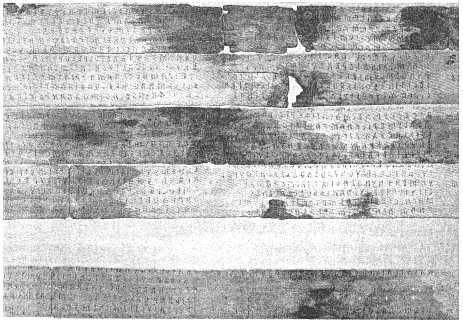

The mummy of Zagreb with fragments of the Liber Linteus

The mummy of Zagreb with fragments of the Liber Linteus

One must imagine the linen book as a harmonicawise folded piece of linen cloth, containing 12 pages. The book looks more like a codexthan like a bookscroll (volumen). Each page has a column of text, originally consisting of 35 lines in black ink between two vertical margins in red ink (width: 24 cm).

All lines are from the right to the left. There was no overwriting of the left margin; eventually, a word was broken off and the rest of this word was written above the line, from the left to the right! This is a reminiscence of the archaic boustrophedic way of writing, which can be seen in the Etruscan text on the Tile of Capua. Sometimes, a red horizontal line marks the beginning of a paragraph.

An Etruscan urn in the shape of a Liber Linteus

An Etruscan urn in the shape of a Liber Linteus

In Egypt, the book cloth had been rigorously torn into 5 binds. Bind 4 (length: 303,5 cm) contains a horizontal piece with the texts from column II until XII. Bind 2 (length: 269 cm) contains the texts from column IV until XII. Bind 1 (length: 302,5 cm) contains the texts of column II until XII. Bind 5 (length: 319,5 cm) contains the texts from column I until XII. Finally, bind 3 (length: 153,8 cm) contains the texts from column VIII until XII, together with a piec without text, which apparently served as the folder of the book.

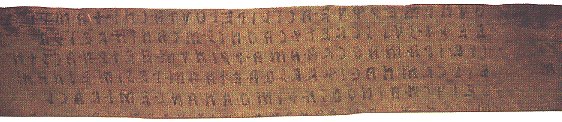

Fragment of mummy bind with ritual text

Fragment of mummy bind with ritual text

The total length of the book originally was 12 cm by 29.6 cm, its height probably 40 to 44 cm. As to the sizes of the "pages" and the layout, this document resembles to certain Gubbio Tablets, which contain old liturgic inscriptions in Umbrian. By the way, an old Umbrian god from Gubbio (Lat. Iguvium) appears in the text of the Liber Linteus: Grabuvie, in the Liber Linteus appearing under the Etruscanized name Crapsti.

The date of the Liber Linteus is a point of firm discussion. Most recent dating proposals vary from the 3rd century B.C. until the 1st century A.D. The 2nd century B.C. seems to be most likely, because of the fact that a few rare names of gods appearing in the text of the Liber Linteus do not appear in votive inscriptions before 150 B.C.

It is thought that the Liber Linteus was written and made in the area of the Trasumene Lake, according to the form of the lettering used in it. Archaeologists think of cities like Cortona, Chiusi or Perugia.

How the book found its way to Egypt and when this happened is unknown. A possible date for transfer to Egypt could have been 80 B.C., when the Etruscans fled from the actions of the senatorial minded Roman consul Sulla, for example to Northern Africa, like three border stones with Etruscan Inscriptions in Tunesia prove.

Spelling of the words in the Liber Linteus

The many variations and uncertainties in the spelling (f.e. zamtic-zamthic; aiser-eiser; enac-enach) betray that the scribe copied an older text, which probably contained even older texts.

The content of the text can only be comprehended very partially. What is certain, however, is that the Liber Linteus is a liturgical book, giving directions concearning rituals, which have to be conducted on certain dates, for certain deities and on certain places. Some formulas are found frequently, like:

tinsi . tiurim . avils

this means: "dayly, monthly, every year"; or:

sacnicleri . cilthl . spureri . methlumeris enas and variants of this formula

which means: "sanctuaries of Cilth (protective deity?) of cities and their districts".

Column I (the last "page"of the book) is very very fragmentary. Nevertheless, the words zicri . cn . betray "that this (cn having to be written down"(participium necessitatis, more generally in Latin language known as "gerundivum").

From column VI on, dates are given:

VI: zathrumsne: "on the twentieth"; eslem . zathrumis . acale: "June 18th"

VIII:thucte . cis . saris": "August 13th"; celi . huthis . zathrumis: "September 24th"

IX: ciem . cealchus: "on the 27th"(30-3)

X: ciem cealchuz: "on the 27th" (30-3)

XI: eslem . zathrum: "on the 18th" (20-2); eslem . cealchus: "on the 28th"(30-2); thunem...ich . eslem . cialchus: "on the 29th of..as well as on the 28th of.."

XII: thunem . cialchus . masn: "the 29th of Masan" (30-1)

On this last date, a sacrifice had to be made in the sanctuary of Uni (unialti). Strikinly, in the short text of Pyrgi on the golden plaques found there, the month Masan is mentioned as a time to pay honor to the goddess Uni. So this points out to a more than three century old tradition.

Column VII seems to be a melodious hymn with a formal diction:

male . ceia . hia...aisvale

male . ceia . hia.....ale

male . ceia . hia.....vile . vale

staile . staile . hia etc.

The columns mention the following deities:

I: introduction

II: Farthan aiseras seus (genius of Aisera Seu)

III: Crapsti (probably identical with the Umbrian god Grabuvie; Grabuvie is also thought to be an Umbrian cognomen for Iuppiter, Mars and the god Vofionus; Crap- can have been originated out of Grab-)

IV: Crapsti

V: Aiser sic seuc (Aiser Si-Seu-c/The Gods Si and Seu); Aisera Seu

VI: Lusa and Lustra, Crapsti, Ati Cath (mother Catha), Luth and Cel

VII: "hymn"

VIII: Culscva, Nethuns(i.e.Neptunus)

IX: Nethuns

X: no known diety names

XI: Velthina (?), Veive (i.e. Veiovis), Satr (i.e. Saturnus)

XII: Aisera seu

The text contains directions to priests (cepen) in the form of imperatives: "libate, sparkle water on...put down....". The nature of the ritual actions varies from god to god. Thus, Aisera has to receive a kletram srenchve (an ornamented bowl?). Vinum, wine is meant for Crapsti and rites concearning the statues (fler) of Lusa, Crapsti and Neth are mentioned. offering tools mentioned consist of a spanti, a type of vase, the word occurs in Umbrian as well; furthermore, a puth,cup, pruch and prucuna(from the Greek word 'prokhous': kanteen). Some offerings, like vacl, mlach, zusleva also occur in archaic Etruscan inscriptions, f.e. on the Tile of Capua.

It is thought, that the ritual text was not used in a public sanctuary. Column XII mentions unialti . ursumnal athre, an atrium in the temple of Uni of Ursmna. If Ursmna is a family name (and a family with the Latinized name of Ursuminiis known in Chiusi, this liturgical book has been probably used for a private cult.

Links to more information on the Liber Linteus:The Etruscan Liber Linteus, by Gabor Z. Bodroghy

The Linen Book (Liber Linteus), by Paolo Agostini

Close fragment of the Liber Linteus texture

Close fragment of the Liber Linteus texture