The Development of Etruscan Cities

by Thanchvil Cilnei

Etruria has an ordinary variated landscape: next to maintains and hills there are lakes (mostly filled craters of exstincted volcanoes) and rivers. De earth is rich of silver, iron, copper, zinc and lead. These metals were especially found abundantly in Northern Etruria and they were already known by the ancient settlers(1). Inland the soil is fertile, especially for growing olives, grapes and granes. This was the most important source of income for the inhabitants in the region of Orvieto and Viterbo.

Etruria is divided into a Northern and a southern region; the natural border between these two regions is a line between Vulci, lake Bolsena and Orvieto.

Southern Etruria is a volcanic tufa-landscape with deeply grinded valleys, high plateaus, crater lakes and rich vegetation. Settlements on the steep tufa-plateaus (good natural fortresses) laid relatively close together, because the people chose to live on the plateaus for their own safety. The settlements therefore must have been quite crowded.

The large city centers of Southern Etruria were sea-orientated; sea- and inland-trade was the main source of income; this trade gave the Southern Etruscan cities great wealth and cultural blooming in the period of the 7th until the 5th century BC.

Northen Etruria geologically contsists mainly of limestone and sandstone hills. The land was in antiquity less densely occupied than Southern Etruria. The North was more country-orientated, agriculture being the main source of income in these parts. the development of wealth and culture got on slower in the Northern city centers(2): the Northern Etruscan cities attained their cultural peak in the period between the 4th and 1st century BC(3). There are two exceptions: Populonia (Fufluna) and Vetulonia (Vetluna), the big Northern Etruscan coastal cities, where in the 9th and 8th centuries BC iron was found and made into artifacts, knew a faster development. They obtained through the trade of iron tools, artifacts and weapons a mighty monopoly, and this led onto a kind of wealth in the 5th century BC, which Southern Etruria had experienced before already. Populonia and Vetulonia, however, were only one part of Northern Etruria and how much their backland could profit, topographically and demographically, from their wealthy situation, is not clear.

Etruscan cities to the North were situated on hills and mountain slopes. They needed artificial fortification by means of city walls.

Despite of the fact that Southern Etruscan cities were orientated towards the sea, there has only been one urban center in all of Etruria, lying directly at sea: Populonia, a Northern Etruscan city. Cities to the South, like Caere, Tarquinia and Vulci, as well as Vetulonia to the North, were built several kilometers inland, for strategical and climatological reasons. They built their respective harbor towns with emporia, like Pyrgi, Gravisca and Telamon.

Futhermore, there were, next to the cities on hill- and mountain slopes, the lower situated places, the settlements on the plains and lagunes of Etruria, like Bologna and Spina.

The form of the cities, the nature of city walls and building of necropoli was traditionally determined by the geological structure of the landscape where a people settled. Etruscan cities often emerged from the same places where their Villanovan predecessors, little nuclei of settlement with their own small necropoli and surrounded by some farmland, had been. The Etruscan cities looked like what Classical Archaeology likes to call a "polis", with clear regional features, which therefore differed from one region to another. This makes it a bit difficult to determine a city's territorium or "hindland', but with the information found in literary sources, especially Latin Literature, some clarity can be gained. Supposing that there has been a clear regional division by the time the Romans took over Etruria, then the Romans would have no reason to change this division. The Roman Imperial division (which thus could have been an update of a former Etruscan one) has been taken over by the Roman Catholic Church in their division of the land in dioceses. Because of the lack of Etruscan scriptures, from which some kind of a "Forma Territoriorum Etruriae" could be reconstructed, archaeology depends on:

1. inscriptions on so called "tular"-stones, or: border stones(4).

2. data from the Latin literature, predominantly dating from the first century BC and the first century AD.

3. diocesal indications from the late Middle Ages; this source is clear and complete, but the date of it is rather late and therefore must be handled with some scepsis.

4. research into the influence of workshops within Etruscan cities on artifacts found in the "hindland" of a suspected ancient Etruscan settlement. This research can give some trustworthy indications on cities and the size of their territoria.

In the 18th and 19th centuries AD the names and locations of most Etruscan cities were still uncertain and the subject of much discussion. Modern archaeology has brought more clarity into this. Some Etruscan urban settlements, among which most of the cities belonging to the League of Twelve, have been located by now. More and more information is gained by recent surveys and excavations in the Tuscany Area and a wide variety of research has been done on the results of these surveys and excavations: these results vary from answers to questions about the planning of the cities, their size, their form, the necropoli, the connection with the territoria and the social structure within the urban settlement. Some difficulty is given with the fact that lots of ancient Etruscan settlements are located on places still inhabited today. Especially if we're dealing with the plateau-cities, we have to bear in mind that they contain an urban development from ancient times until this very day.

Authentic Etruscan city parts have been excavated in Marzabotto, Spina, Acquarossa, San Giovenale and Roselle. Veii has never been completely excavated, only partially; nevertheless, its excavation has brought to light lots of information about the city's form and functioning.

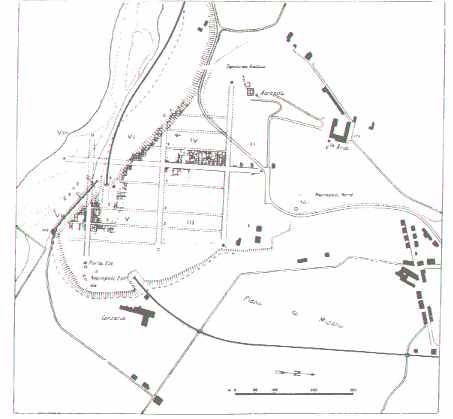

city

plan of ancient Veii

city

plan of ancient Veii

Especially in Southern Etruria there is some possibility to excavate whole ancient Etruscan cities, because these locations are not inhabited anymore today. In Northern Etruria, especially inland, cities like Arezzo, Cortona, Volterra, Chiusi and Orvieto were not abandoned, but they developed during the times of the Roman occupation and afterwards, until today. Excavations at these places have only been carried out on certain points, mostly connected to the demolition of a building or the making of a new road. Few things are known about the plans of Tarquinia, Caere and Vulci, but the conditions for research are quite good here. Vulci and Vetulonia have been partially excavated: some "quarters" from Hellenistic and Roman fases of both cities.

city

plan of Marzabotto

city

plan of Marzabotto

From literary sources and images from Roman antiquity we can learn, that the foundation and planning of a city in Etruscan civilization was a matter which was carried out by strictly established and prescripted ritual rules, which have been predominantly handed over to us in the Libri Rituales(5) and the Libri Tagetici, called after Tages, the legendary Etruscan prophet, who was told to have given the Disciplina Etrusca to the Etruscan people. These titles point out that we are dealing here with an Etruscan tradition, that has been taken over (very accurately) by the Romans and was carried out by the latter very strictly in the foundation of their colonies in Italy and elsewhere.

The basic outlines of the city, from which the planning began, were established according to the directions of the augures, who had studied the flight of the birds regarding this matter. When the outlines of the city had been established, they were marked down by ploughing a furrow, the so called sulcus primigenius, which was only to be interrupted at the places where a tower or a city gate had to be built(6). City plans like this one, ideal in form with rectangular insulae, the so called Hippodameic city plan, have been recovered at Marzabotto, Spina and Capua. These examples however are exceptions to what has been found more often. The Etruscans probably took over the Hippodameic system from the Greeks of Southern Italy and applied it only then, when there was full opportunity to use it, for example in case of the foundation of a complete new city like Bologna or Marzabotto. The Romans, with their practical view and feeling for order and proportion in building techniques, were fond of applying these originally Greek ideas, but only in case of the foundation of new cities, predominantly colonies, or the expansion of occupied cities in the provinces (like Pompei, were quite a few Roman army veterans were settled as colonists) and the building of army camps (castra). A quick view at the map of ancient Rome (Forma Urbis Romae) will not produce the discovery of a Hippodameic city plan in the Eternal City...This makes clear that Rome is a city which developed, in spite of the myth of the foundation of Rome by Romulus. This myth probably functioned as a story in which the Romans liked to explain the unification of a number of loose villages, inhabited by groups or "clans" who had some genetic relation to neighbor groups, all situated around or in the vicinity of what was later to become the central market place of Rome, the Forum Romanum. These groups found themselves unified by some outside intervention: Romulus and Remus, whoever they were, but according to the myth not from that very place but from a town called Alba Longa. A further and probably even more important unification, complete with legal and political institutions, was established with the coming of groups of Etruscans to the town Rome. So, in the myth, Romulus did the ploughing of the sulcus primigenius, which was done at the foundation of a new city, which was to be built. Latin texts that refer to the ploughing of the sulcus primigenius, provide some information, not only about the religious aspects of this tradition, but also about the political and strategic aspects. Ploughing a furrow not only meant to build a ramp, a fence or a wall, but also: to gain control over the countryside surrounding the city, just by building that ramp, fence or wall. Just like the Etruscans and much later the Romans did when they founded their colonies and ploughed the furrow to build a fortification around the city, Romulus was told in the myth to do this, because he might have wanted the little villages on the Seven Hills to unite and to be called one City, which would dominate the surrounding countryside, like it were hers.

This leads to the fact, that cities like Marzabotto, Bologna, Spina and Capua, which were founded by the Etruscans with certain goals, could be planned completely in advance. Furthermore, they are not as old as the conventional city types in these areas. These latter mentioned cities are very old. In respect of Etruria, Latium and other regions, the fact stands, that these very old cities might have known their foundation legends and myths (some of them have been passed down to us through the Latin literature), just like Rome, but that these legends and myths might well have had the same function as has been mentioned above in the case of Rome. So, in spite of a recorded legendary foundation, they were more likely to have developed in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, or maybe even earlier, out of Villanovan "predecessors"(7).

Like the Etruscan culture had an important predecessor in the Villanovan culture(8), old Etruscan urban centers have developed at locations, where in the Villanovan Period (about 900-750 BC) clusters of villages, of huts, had stood, which became bigger groups as time went by and then separated from villages further away, who eventually did the same thing. A similar development can be seen throughout the Mediterranean area during this period; in the Near East the same development took place some centuries earlier. This change from a cluster of huts into a village and from a group of villages into a town, city or urban center, takes place through gradual infrastructural innovation and improvisation of a same scale as the social one. This includes that little rivers just run through a developing city, that roads are not straight and directed to a certain fixed point, for example the North. Generally, they are very old and lead to the sea or into the mountains. Cities like that have existed in the Greek world and they always have existed, until the built city came into fashion, next to the developed city. This phenomenon appears to have occurred for the first time in Asia Minor, where the Greeks founded their first colonies in the 8th century BC, very often at locations where before that time no man had ever lived(9).

Proofs of the fact that the oldest Etruscan cities were not coordinated and therefore developed out of clusters of villages is given by excavations, at which parts of Veii, Acquarossa and San Giovenale (10) have been revealed. In the 6th century BC however, in these city types a tendency starts to carry out the city expansions using the Hippodameic system. This tendency is most evident in Acquarossa and in the necropolises of Cerveteri and Orvieto. Although we can speak of a tendency here, archaeologists like to call it more an experiment than common use, because other parts of the Etruscan region have shown that city development in the Archaic Period (6th-5th centuries BC) was more likely to be a matter of a continuous process of expansion than of an expansion, which was planned on forehand. Even cities like Vetulonia, called Hellenistic, because of their predominant expansion during the 4th onto the 1st century BC, do not show a complete Hippodameic pattern. This was often not possible, because the topography of the city would not allow this kind of urban expansion.

Generally, a city in the Etruscan Period ( I would like to designate this period to the time between about 700 BC and the Annus Domini) consisted over paved streets and roads and a drainage system. The best archaeological example for this is offered by the excavation of the city of Marzabotto, which was a planned building project from scratch and was built around 550 BC. Cities on plateaus (mostly in Southern Etruria) were usually outfitted with a delicate system of underground drainage, the so called cuniculi.

Some cities consisted of a large territorium. Research from the air and surveys have lead to data, on which can be assumed that the area belonging to Cerveteri consisted of about 150 hectares and that the area belonging to Tarquinia consisted of about 135 hectares. American and Italian researchers have tried to establish the size of the territoria of about 40 larger and smaller Etruscan sites in global numbers of hectares and hereby to reconstruct a map of ancient Etruscan urban centers and their territoria (11).With some certainty it can be assumed that a territorium was not completely inhabited. This can be assumed in some cases of the enwalled city as well. It is difficult to establish a view on how many inhabitants a city counted. The survey on the cities and their territoria is therefore somewhat misleading, because only numbers of hectares of land are given and no numbers of inhabitants on these pieces of land. To get or give a view on the numbers of inhabitants in a certain city in a certain period, we can take a look at the results gotten by surveys and excavations in burial fields and tomb clusters in the vicinity of the city. The period which can be seen as the most interesting one in this respect is the Archaic Period. As a result from research in the Caeretan necropolis of the Archaic Period (the most flourishing period of this city), anumber of inhabitants of about 25,000 could be reconstructed, which must have been quite a number in those days.

Whether an Etruscan city was actually surrounded by a city wall, depended on the location of the city and whether the city was being threatened from outside forces or not. To build a wall obviously served a protecting purpose: to protect yourself from intruders, wherever they might come from. Southern Etruscan cities, often situated on high and steep plateaus, barely needed any kind of wall: the plateaus were high, the valleys were deep, because the small, quickly floating rivers had grinded out these valleys in the volcanic rock. At some places in these cities, the natural fortification was completed by a wall or a piece of it.

In Northern Etruria the geology of the countryside differed from the South, so the people had to fortify their complete city, or at least a considerable part of it, with a wall. These walls were built in a ring or oval form around the urban center and probably the area which lay directly next to it. The necropolis usually remained outside the city walls. In the earliest period, the material for building some kind of a permanent wall consisted of sand and soil. In the 7th century BC people in Northern Etruria began to build walls out of baked tiles and natural stone (12). The best example of this wall, still to be seen in place, is the archaic city wall of Roselle. In building stone walls in the Archaic and Classical Period, the local kind of stone was commonly used, because of the fact that the blocks had to be large and were difficult to carry over a large area. Most kinds of stone in Northern Etruria were volcanic: sandstone, limestone and travertine were used; in the South the city walls, if they were necessary, were built of the abundant tufa stone.

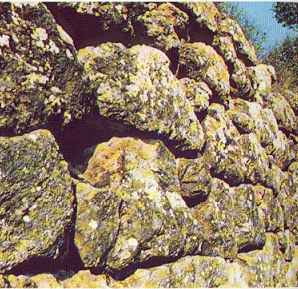

the

oldest part of the Roselle city wall

the

oldest part of the Roselle city wall

City walls had to be permanently kept in good shape against attackers of all kind. Therefore they were rebuilt, reshaped, expanded and fortified in the course of time. This is why the dating of the oldest building phase of an Etruscan city wall is a problem in most Etruscan cities: the oldest phases mostly have been hacked away and replaced by other and better fortifications. At some places, like in Roselle, fragments of the oldest wall have been preserved and revealed. Building phases of city walls can be dated in several ways: the shape of the blocks and the way they were worked, the form of the wall and the development of towers and gates, but also dating can be done by examining all kinds of findings, found between the joints of the stones within the wall. If these findings are at hand (which is rare), an archaeologist can say something about the age of a (piece of) wall by dating the findings (pieces of bone, clay artifacts, potsherds, etc.).

Technically spoken, three kinds of city wall building can be distinguished:

A. Opus Incertum

This is also called the "Cyclopean" or "Pelasgian" wall; think of the walls that surround the fortresses of Mycenae and Tiryns in Greece.

B. Opus Quadratum

This kind of wall has stones which have been carved and hacked more regularly than in Opus Incertum.

C. Opus Polygonale

The youngest form of wall building found in ancient Etruria.

The oldest known city wall in Etruria, the one at Roselle, dates in his oldest phase about the second half of the 7th century BC. This wall consisted of a stone socle and on top of this a construction of mud bricks. Findings of potsherds within the joints of the wall date this construction between 650 and 600 BC. This construction of mud bricks on a stone socle is known at sites in Asia Minor dating late 8th/begin 7th century BC. Next to the wall at Roselle, the only city wall in Etruria, as old as the one at Roselle, exists in Vetulonia.

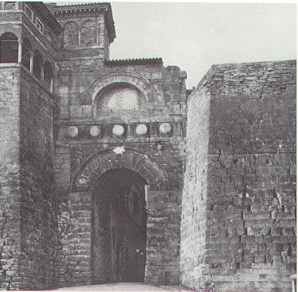

the

city wall at Perusia (Perugia) with a gate.

the

city wall at Perusia (Perugia) with a gate.

Most of the actually known Etruscan city walls date from the period 4th until 1st century BC en it can be assumed that the city wall as a permanent means to defend the city from intruders proved to be necessary only from the 4th century BC onwards. This was a time in which the Etruscans regularly had to fear danger from intruders from the North (the assaulting Gauls, who invaded Italy at the time) and from the South (the Romans, who fought against both the Gauls and the Etruscans and who were gaining more and more power and territory as the time went by). In the 4th century BC, Etruria had already lost her rule over the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Greeks of Southern Italy and Sicily. Examples of huge city walls in Etruria of that period can be found at Volterra, Fiesole, Arezzo, Cortona (in spite of its high location), Perugia (view picture), Bettona, Chiusi, Populonia and Tarquinia.

Opus Quadratum-walls built in tufa stone in Southern Etruscan cities like Veii, Caere and Vulci can often barely be distinguished from later phases from the period of the Roman Republic, the Roman Imperium and the Middle Ages. Some have come to the conclusion that the way of building these walls, begun by the Etruscans, has been copied for a long time by the Romans and their followers. But, as the ancient Etruscan building phases are mostly hard to distinguish from the rest, as was mentioned above, it is hard to say anything certain about this.

In sacred Roman scriptures passages can be found about the ritual foundation of a city and the description of the marking of the city wall to be built by ploughing a furrow, only interrupted by the places where towers and gates had to be built. How these passages have to be interpreted is not certain. Generally it is assumed that Etruscan city walls did not have any towers before the Hellenistic Period. Some exceptions for this exist, but there is not much known about this phenomenon. Steingraeber and others presume that the oldest wall and tower constructions were made out of wood. In Roselle, some remains of towers from the 6th century BC have been found: the northern tower probably consisted of an inner room. Towers with arcades only appeared during the Hellenistic Period, like the above mentioned features in Perugia, Volterra and in Falerii Novi. These arcades would not have been Etruscan device, but more likely a feature taken over from city walls in the Greek colonies of Southern Italy (13). The towers with the round arcades in Perugia, Falerii Novi and Volterra werd decorated with small stone heads ("protomoi"), which is typical for the end of the 3rd century BC. In spite of that, only the tower of Falerii Novi can be dated with certainty, according to the findings of potsherds and other datable material inside the wall, from about 210-200 BC (14).

Literature:

Steingraeber, S., 1981 Etrurien: Staedte, Heiligtuemer, Nekropolen, Muenchen, passim.

Ward Perkins, J., 1961 Veii: Historical Topography of the Ancient City, PBSR 29, London, passim.

Ridgway, D. and F., 1979 Italy before the Romans: the Iron Age, Orientalizing and Etruscan Periods,

London, passim.

Potter, T.W., 1979 The Changing Landscape of South Etruria, New York, 37-91.

Hiller, F. 1962 Zur Stadtmauer von Rusellae, RM 69, 59-75.

Judson, S. and 1981 Sizes of Sttlements in Southern Etruria: 6th and 5th Centuries BC, SE 49,

Hemphill, P. 193-202

Notes:

(1) Metals were predominantly found in the Tolfa Mountains, the Monte Amiata, near Populonia, Vetulonia and on the Island of Elba.

(2) The aspect of trade and therefore the contact with other peoples was less important here.

(3) One should take under consideration that the romanization of Etruria came on well in the 3rd and 2nd century BC, and that by the 2nd/1st century BC a considerable part of Etruria had been romanized already.

(4) The inscriptions designate these stones as borderstones (the Etruscan word "tul-/pl. tular" means "border/territory"). These borderstone inscriptions are in Etruscan and they appear here and there at an excavation. They do not determine complete territoria; they are too scarce a finding for that. Studying them is interesting, but a lot of problems still have to be solved. Still they prove that the Etruscans used stones to mark their territoria.

(5) Libri Rituales: books consisting all the rituals that had to be taken under consideration in daily life. These rituals were passed down to the Romans by the Etruscans. The Romans called everything concerning divination and very ancient practices of divine worship "Disciplina Etrusca" and the rituals were put together in books called the Libri Rituales by the Romans.

(6) i.e.: the places which were found important in the 19th century: the Portonaccio Sanctuary at Veii, excavations at or near the remains of the ancient city wall, Villanovan necropolises, Etruscan necropolises and votive deposits.

(7) View Servius' commentary to Virg. Aen. V 755.

(8) How the development of the cities might have taken place is the issue of much discussion at the moment. View: Harris, W.H., 1989, Invisible Cities: the Beginnings of Etruscan Urbanization, Atti del Secondo Convegno, Roma, 375-392.

(9) Although the influence of trade contacts with Greeks and Phoenicians should not be underestimated at this point.

(10) Written and oral traditions have preserved so called foundation myths/legends, in which the issue often was: the assignment by a local ruler of an (uninhabited) piece of land to colonists.

(11) Some Etruscan cities are not known by their Etruscan name. Therefore they are called (in this article) by their Italian or Roman name, i.e. sometimes the name of the Italian town in the vicinity of the ancient site of an Etruscan city or urban center (f.e. Marzabotto).

(12) Judson, S. and Hemphill, P., 1981, Sizes of Settlements in Southern Etruria: 6th and 5th Centuries BC, SE 49, 193-202.

(13) Hiller, F., 1962, Zur Stadtmauer von Rusellae, RM 69, 59-75.

(14) Like for example the Porta Rosa in the Southern Italian town Velia.

Generally this ornamentation on city towers can be seen on Hellenistic urn reliefs; the period in which these reliefs were made is from 300 BC until the early Roman Imperial Age.