the Pesaro inscription

the Pesaro inscriptionBilingual Inscriptions in Etruria

by Thanchvil Cilnei

Bilingual inscriptions, Etruscan texts with some kind of a translation in Latin, are the easiest way to get deeper into an almost unknown language like Etruscan. Unfortunately, within the range of the Etruscan inscriptions, there are very few bilingual inscriptions, that have made it through the ages. In fact, only one serious bilingual inscription exists, which has been found only quite recently, when de study of the Etruscan language had come a long way already. Besides, the inscription didn't yield much information after all. Furthermore, there are about thirty inscriptions that could be called more or less bilingual, but which do not learn us very much about the structure of the Etruscan language, because they merely consist of an Etruscan name, which has been translated into Latin. Most bilingual inscriptions obviously date from the late Etruscan period, i.e. from the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C., because of the strong influence from Rome. Nevertheless, they are quite interesting. We will have a look at some of them.

An exact registration comes from a burial tile from the Clusium region:

TLE 514:

l . cae . caulias'

lart cae caulias

The second line is in Latin lettering. From this inscription we only learn that the Etruscan abbreviation l . stands for the name lart (that is to say: the Etruscan spelling of this name almost always ends up with Larth). The above standing example is called a "pure translitteration": the Etruscan inscription has been translitterated letter by letter.

Also in the following inscription, we see an exact description in Latin lettering what the Etruscan words say:

TLE 540; from Clusium:

l . purni . l . f

l . purni . l . f

Lucius Purnius, son of Lucius

This is even more uninteresting for the study of the Etruscan language, but nevertheless interesting after all: the inscription is a Latin formula (with the Etruscan family name Purni), which has been rendered into Etruscan writing integrally, for the letter f , which stands for the word "filius" is Latin! Sometimes the Latin version contains elements that do not occur in the Etruscan version, because they do not seem to exist in Etruscan. We see this on a stele in Clusium,

TLE 462:

c . treboni . q: f. gellia natus

cae trepu

C(aius) Treboni(us), son of Q(uintus), son of Gellia,

Cae Trepu

Here, only the last line is in Etruscan writing. We can, however, see one or two things in this inscription. Cae corresponds to C(aius): -e is an Etruscan name-ending which occurs a lot. Transcribing Treboni(us) into Trepu or vice versa, we can see that p becomes b and u becomes o, or vice versa. This is what we have see before in the study of the Etruscan Language, compared to other ancient languages of Italy. Another text shows the correspondent of the phrase which deals with the mother-child relationship (using the word "natus"):

TLE 521; urn from Clusium:

arth canzna varnalisla

C. Caesius C. f. Varia nat

Ar(n)th Canzna, the (son) of Varna

C(aius) Caesius the son of C(aius) and the son of (i.e. born from) Varia

Varia will, therefore, be the name of the mother. That name has to correspond with the Etruscan name Varna. The word varnalisla has to mean something like "the/that (son) of Varna". The Etruscan text contains, by the way, if we are not mistaken here, a mistake: the word should have been spelled as varnalisa, not varnalisla. The form -isla is a genitive, which does not fit in here.

Two different cultures are depicted on an urn from Clusium:

TLE 925:

senti vilinal :

Sentia. Sex. f.

Senti (daughter) of Vilina

Sentia daughter of Sex(tus)

In Etruscan, the name of the mother is given (in the genitive, this would be vilinal), whereas the Latin text gives the name of the father.

From other inscriptions we get a few Etrsucan words and find out what they mean. An inscription from an Arretine urn shows:

TLE 661:

C. Cassius C. f. Saturninus

vel . canzi . c. clan

C(aius) Cassius, son of C(aius) Saturninus

Vel Canzi, son of C(ae)

We find out here, that the Etruscan word clan means "son", but that has been made clear through other studies of the Etrsucan language, so we know that already; still, it is an example of what we might find out in the future what we don't know yet. Furthermore, a remarkable thing in this inscription is, that the Etruscan name vel has been replaced by Caius in the Latin version. Obviously Vel was not a Roman first name and so the author, or maybe the person who had the urn inscribed, decided to choose another first name in the Latin version of the inscription. Another example of this phenomenon gives the following inscription on an urn from Clusium:

TLE 472:

Q. Scribonius C. f.

vl . zicu

One might think that Scribonius ('writer"/"Writerman") is a translation of the Etruscan zicu, for a verb zichu("to write") is known to us. Interesting is the following inscription:

TLE 608, from Perugia:

ve . tins' . velus' . vetial . clan

Vel Tins' , son of Vel (and) Vetia

And elsewhere, in the same grave as where the preceding inscription was found, the following (a so called "pseudo-bilingual inscription"):

C. Iuventius C. f.

The family name Tins' is depicetd here as Iuventius<*Iov-ent-ius. Now Tin(s') is the name of the most important Etruscan god, equal to Iuppiter< *Iov-pater, gen. Iov-is.

* The words noted with a starlet are non-existing words, but, mostly, combinations of Indo-european stems, of which the existing ancient Greek, Latin or, sometimes even Etruscan words are, accorinding to linguists, believed to have been developed of.

Another familial term, i.e. lautni, occurring regularly in inscriptions, is translated on a Perugian urn:

TLE 606:

L. Scarpus Scarpiae l. Popa

larnth . scarpe . lautni

L(ucius) Scarpus, f(reedman; l(ibertus)) of (the) Scarpia (family), Popa

Larnth Scarpe, freedman

In Rome, a freedman took on the name of the family he formerly belonged to as a slave, in this case: Scarpus. The Latin word Poap, here used as a cognomen, means: a priest's assistant.

A word which is otherwise unknown to us from inscriptions is the following on a funeral tile in Clusium:

TLE 541:

ath: trepi: thanasa

Ar. Trebi. histro

A(rn)th Trepi (the) Actor/actor

The Latin word "histrio" means "actor" (in a theatre). Thanasa therefore could mean "actor". Strangely enough, the Latin word for that profession, "histr(i)o", is of Etruscan origin as well. So maybe the word thanasa doesn't mean "actor" at all, maybe it is some sort of a cognomen. We cannot be sure about it from this inscription, which is the only one with the actual word on it...

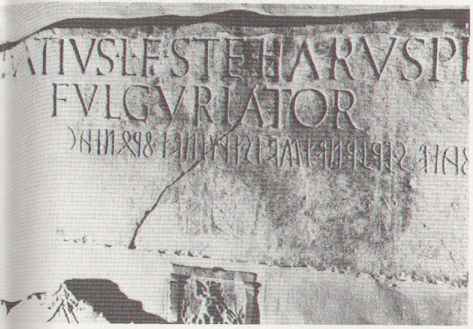

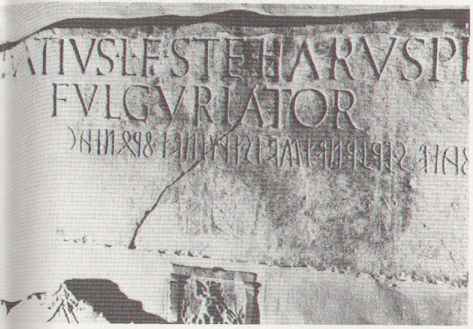

The bilingual inscription of Pesaro

On the fron of a limestone funeral case from Pesaro (ancient Pisarum on the border of the Adriatic Sea) is a bilingual inscription of some importance:

the Pesaro inscription

the Pesaro inscription

TLE 697:

[L. Ca]fatius. L. f. Ste. haruspe[x] fulguriator

cafates.lr.lr.nets'vis.trutnut.frontac

The inscription is generally dated in the 1st century B.C. The first two lines are given in Latin:

L(ucius)[Ca]fatius, son of L(ucius), born in the Tribus Ste(llatina), haruspe[x](= seeer of entrails), fulguriator (=seeer of lightning). The third line gives the Etruscan:

L(a)r(is) Cafates, son of L(a)r(is), nets'vis(=haruspex), trutnut, frontac(=fulguriator).

It is assumed that Lucius Cafatius and Laris Cafates are one and the same person, born in the environment of either Tarquinia, or Cortona or Pesaro, for these three towns are believed to belong to the Tribus Stellatina, mentioned in the inscription. According to the shape of the lettering in the stone and the finding place, Pesaro seems to be the place most likely for our man Laris Cafates to have originated from. What is interesting is, that the Latin text only gives two offices our man executed, while the Etruscan text provides three: nets'vis, trutnut, frontac. This discrepancy has stirred a lot inside the world of Etruscology. Let's have a closer look at these three words:

Nets'vis:

There is hardly any doubt about the meaning of this word. the stem of the word, nets', resembles the Greek word nedus (=belly). An Italic scarab shows an haruspex with the inscription natis. Maybe the word-ending -vis can be compared to the Latin word-ending -spex, so -vis = -spex, which means "viewing/viewer/seeer". Cf. -vis to the Indo-european *Fid-, like for example Lat. vid-e-re, and Greek (aor.) eidon.

Frontac:

Opinions are divided about this word. The letter -o- seems to be genuine, although quite unique within the Etruscan language. Therefore, it is believed that this word is a loan-word from another language. It has been compared to the Greek word bronte (=thunder), but also to the Indo-european stem*b(h)rento- (horn). The thought behind this might be that the Greek word keraunos (akin to *b(h)rento-???) can mean both "lightning" and "horn". This being true, however, the whole explanation of the word remains weak to me. Furthermore, it has been supposed that the ending -ac in the word frontac is the signification of the acting person, the one who does the thing mentioned in the first part of the word, like in the also appearing Latin word fulguriator. The ending -tor/-trix(f) in Latin denotes the acting person: someone who does .....by means of profession, maniacally or is the definite doer of some special action (like: "auctor" = founder). So if -ac = -tor and if frontac = fulguriator, the word frontac means: "being able to/being in the position to interpret the lightning/lights in the sky".

Trutnut:

Last, but not least, the much discussed word trutnut. It is mentioned only once more as the description of some sort of office. This word, too, has been interpreted as a loan-word, which would be akin to the Latin word trutina and the Greek trutine, which in both cases means: "weighing balance/machine".Trutnut, therefore, couls mean something like "weigher/seeer/priest who sees divine decisions". Apparently, the Latin language could not provide an appropriate synonime for this word, so it is not mentioned in the Latin version of the inscription. A solution for this problem can be found in Cicero's divination book De divinatione. According to him, the Ars Haruspicina was divided into three sections:

the extispicium: the viewing of entrails, like liver, lungs, heart and stomach

the divination of fulmina: the studying of sightings of fires and lightning in the sky

the divination of prodigia, ostenta: the studying of omens and sightings that deal with the will of the gods.

This means, that the function of an haruspex is threefolded. In our case here, one could conclude that trutnut is some kind of priest who interprets omens like miscarriages, rains of stones, earthquakes and the like. Sometimes, Cicero speaks about these functions separately, like in 2,109: "et haruspices et fulguratores et interpretes onstentorum"("both the liverseeers, the seeers of lightning and the interpreters of omens").

Probably the author of the Pesaro-inscription thought that the last description (of the word trutnut) would be too elaborate and held the opinion that haruspex can also mean both nets'vis and trutnut. We furthermore know the word trutvecie from an Etruscan dedicatory inscription on a bronze statue:

TLE 740:

tite : alpnas : turce : aiseras : thuflthicla : trutvecie

Tite Alpnas gave (this) to Aisera Thuflthicla because of an omen (?).

The old interpretation ("based on a dream sighting" as translation for trutvecie) does not have to be untrue because of our interpretation...

Literature:

Beekes R.S.P. & Meer, L.B. van der, 1991, De Etrusken Spreken, Muiderberg, pag. 27-32.

Pallottino, M., 1968, Testimonia Linguae Etruscae (TLE), Firenze, passim.

Pfiffig, A.J., 1975, Religio Etrusca, Graz, passim.