Mary Griffith Story

pflagdc.org article

source

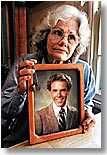

Mary Griffith's story perhaps reflects the ultimate human tragedy. She blames herself for the death of her son.

Mary says Bobby was "kind and gentle, with a fun-loving spirit." He was handsome, with clean-cut features and an Adonis-like body perfected by weight lifting. He loved old movies, particularly The Seven Year Itch with his favorite star, Marilyn Monroe. He loved Italian food and meeting people.

But the diary that he kept for the last two years of his life reveals a tortured soul. Tortured by passions he had been taught were sinful. Tortured by the bondage of what he called "society's rules." Tortured by fear of hell. "Gays are bad," he wrote, "and God sends bad people to Hell.... I guess I'm no good to anyone, not even God. Sometimes I feel like disappearing from the face of this earth."

The Griffiths attended Walnut Creek Presbyterian Church in Walnut Creek, California. There, Mary said, the ministers and the congregation were clear that homosexuals were sick, perverted, and condemned to eternal damnation. "And when they said that," Mary recalls, "I said, 'Amen.'"

For her part, Mary just knew that homosexuality was "an abomination to God." And even before she knew Bobby was gay, she conveyed her feeling to him in no uncertain terms. She remembers in sadness one incident that occurred when Bobby was fourteen. He had introduced her to a friend of his, a young girl. For some reason, Mary had loaned the girl a coat. Later, Mary learned that the girl had once had a lesbian encounter, and found herself unable to wear the coat again herself. "You can't love God and be gay," she told Bobby.

At about the same time, Bobby told his brother he was gay. Two years later, his brother told their parents. That night, the family was up until 4 A.M. talking and crying. They all agreed Bobby was a sinner, that he had to be cured by prayer and Christian counseling. Mary told him he had to repent or God would "damn him to hell and eternal punishment." She had faith that God would come to Bobby's rescue, but only if he read his Bible.

The Christian counselor recommended prayer and suggested that Bobby spend more time with his father. But Bobby's diary revealed that nothing was changing. "Why did you do this to me, God?" he wrote. "Am I going to hell? I need your seal of approval. If I had that, I would be happy. Life is so cruel and unfair."

His mother kept telling him he could change. "It seems like every time we talked, I would tell him that," she says. "I thought Bobby wasn't trying in his prayers." When Bobby became more withdrawn, she simply chalked it up to God's punishment. "Now," she says, I look back and realize he was just depressed."

When Bobby was twenty, in desperation the Griffiths decided he should move to Portland, Oregon, and live with a cousin. At first, the move seemed to help. He worked as a nurse's aide in a senior citizens' home and developed something of a social life. But the depression returned and deepened. A few months later, in his diary, he cursed God and added, "I'm completely worthless as far as I'm concerned. What do you say to that? I don't care." Again and again, he emphasized the shame and self-blame he felt over his sexual orientation. "I am evil and wicked. I am dirt," he wrote. "My voice is small and unheard, unnoticed, damned."

One Friday night in August 1983, Bobby had dinner with his cousin. She noticed that he seemed thoughtful, perhaps depressed. He seemed to want to talk about something, but said little. Then he left, saying he was taking a bus to go dancing downtown.

Early the next morning, two men driving to work noticed a young man, later identified as Bobby, on an overpass above a busy thoroughfare. As they described the next few moments, the boy walked to the railing, turned around, and did a sudden back flip into mid-air. He landed in the path of an eighteen-wheeler.

Bobby's body was return to Walnut Creek for funeral services in the Presbyterian church. The minister told the mourners that Bobby was gay, and suggested that his tragic end was the result of his sinning.

Later, the Griffiths met with their pastor for grief counseling. In her despair, Mary was seeking ways to atone for the loss of Bobby. She told the pastor she knew there were "other Bobbys out there" and asked how she could help them. The pastor merely shrugged his shoulders�and Mary never again returned to that church.

Mary Griffith's story perhaps reflects the ultimate human tragedy. She blames herself for the death of her son.

Mary says Bobby was "kind and gentle, with a fun-loving spirit." He was handsome, with clean-cut features and an Adonis-like body perfected by weight lifting. He loved old movies, particularly The Seven Year Itch with his favorite star, Marilyn Monroe. He loved Italian food and meeting people.

But the diary that he kept for the last two years of his life reveals a tortured soul. Tortured by passions he had been taught were sinful. Tortured by the bondage of what he called "society's rules." Tortured by fear of hell. "Gays are bad," he wrote, "and God sends bad people to Hell.... I guess I'm no good to anyone, not even God. Sometimes I feel like disappearing from the face of this earth."

The Griffiths attended Walnut Creek Presbyterian Church in Walnut Creek, California. There, Mary said, the ministers and the congregation were clear that homosexuals were sick, perverted, and condemned to eternal damnation. "And when they said that," Mary recalls, "I said, 'Amen.'"

For her part, Mary just knew that homosexuality was "an abomination to God." And even before she knew Bobby was gay, she conveyed her feeling to him in no uncertain terms. She remembers in sadness one incident that occurred when Bobby was fourteen. He had introduced her to a friend of his, a young girl. For some reason, Mary had loaned the girl a coat. Later, Mary learned that the girl had once had a lesbian encounter, and found herself unable to wear the coat again herself. "You can't love God and be gay," she told Bobby.

At about the same time, Bobby told his brother he was gay. Two years later, his brother told their parents. That night, the family was up until 4 A.M. talking and crying. They all agreed Bobby was a sinner, that he had to be cured by prayer and Christian counseling. Mary told him he had to repent or God would "damn him to hell and eternal punishment." She had faith that God would come to Bobby's rescue, but only if he read his Bible.

The Christian counselor recommended prayer and suggested that Bobby spend more time with his father. But Bobby's diary revealed that nothing was changing. "Why did you do this to me, God?" he wrote. "Am I going to hell? I need your seal of approval. If I had that, I would be happy. Life is so cruel and unfair."

His mother kept telling him he could change. "It seems like every time we talked, I would tell him that," she says. "I thought Bobby wasn't trying in his prayers." When Bobby became more withdrawn, she simply chalked it up to God's punishment. "Now," she says, I look back and realize he was just depressed."

When Bobby was twenty, in desperation the Griffiths decided he should move to Portland, Oregon, and live with a cousin. At first, the move seemed to help. He worked as a nurse's aide in a senior citizens' home and developed something of a social life. But the depression returned and deepened. A few months later, in his diary, he cursed God and added, "I'm completely worthless as far as I'm concerned. What do you say to that? I don't care." Again and again, he emphasized the shame and self-blame he felt over his sexual orientation. "I am evil and wicked. I am dirt," he wrote. "My voice is small and unheard, unnoticed, damned."

One Friday night in August 1983, Bobby had dinner with his cousin. She noticed that he seemed thoughtful, perhaps depressed. He seemed to want to talk about something, but said little. Then he left, saying he was taking a bus to go dancing downtown.

Early the next morning, two men driving to work noticed a young man, later identified as Bobby, on an overpass above a busy thoroughfare. As they described the next few moments, the boy walked to the railing, turned around, and did a sudden back flip into mid-air. He landed in the path of an eighteen-wheeler.

Bobby's body was return to Walnut Creek for funeral services in the Presbyterian church. The minister told the mourners that Bobby was gay, and suggested that his tragic end was the result of his sinning.

Later, the Griffiths met with their pastor for grief counseling. In her despair, Mary was seeking ways to atone for the loss of Bobby. She told the pastor she knew there were "other Bobbys out there" and asked how she could help them. The pastor merely shrugged his shoulders�and Mary never again returned to that church.

However, she did not lose her sense of religion. Her speech resonates with the tones of spiritual awareness. But she has found a very different God from the one she worshiped at Walnut Creek Presbyterian. She reread her Bible with fresh eyes, and sought out secular books about homosexuality. She concluded that there was noting wrong with Bobby, that "he was the kind of person God wanted him to be...an equal, lovable valuable part of God's creation." She says now, "I helped instill false guilt in an innocent child's conscience."

Bobby Griffith's fate is not uncommon among gay youth. One report chartered by the government suggests that gay adolescents are nearly three times more likely than other teens to attempt suicide. Some 30 percent of all youth suicides, it says, can be traced to the pressures generated by "a society that stigmatizes and discriminates against gays and lesbians."

But Bobby's story stands out for two reasons. Unlike other youths who kill themselves, Bobby left an extensive written record of his anguish. And unlike other parents, his mother has not denied or buried her role in the tragedy, but has leveraged her remorse into aid to others.

Shortly after Bobby's death, Mary Griffith discovered PFLAG. For some years, she was president of an East San Francisco Bay PFLAG chapter and appeared frequently on television talk shows, usually wearing a button with Bobby's picture and another with the PFLAG message, "We love our gay and lesbian children." She has cooperated in the filming of documentaries about the Griffith family tragedy, and is the subject of a the book Prayers for Bobby: A Mother's Coming to Terms with the Suicide of Her Gay Son, by Leroy Aarons, founder of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association and a former national correspondent for the Washington Post. She campaigns tirelessly for the cause of public school counseling supportive of gay teenagers, believing that Bobby would still be alive if his high school had had such a program.

And she has a guiding standard for other parents. Listen to your instincts as a mother or father, she tells them, not to those who urge you to violate your parental conscience. "All we had to do was say, 'We love you, Bobby, and we accept you,' and I know Bobby would be here today. Part of me wanted to reach out and tell him, 'You're fine just the way you are.' To me, that was my mother love, that was my conscience. But I didn't have the freedom to listen to my own conscience."

|

Mary Griffith's story perhaps reflects the ultimate human tragedy. She blames herself for the death of her son.

Mary says Bobby was "kind and gentle, with a fun-loving spirit." He was handsome, with clean-cut features and an Adonis-like body perfected by weight lifting. He loved old movies, particularly The Seven Year Itch with his favorite star, Marilyn Monroe. He loved Italian food and meeting people.

But the diary that he kept for the last two years of his life reveals a tortured soul. Tortured by passions he had been taught were sinful. Tortured by the bondage of what he called "society's rules." Tortured by fear of hell. "Gays are bad," he wrote, "and God sends bad people to Hell.... I guess I'm no good to anyone, not even God. Sometimes I feel like disappearing from the face of this earth."

The Griffiths attended Walnut Creek Presbyterian Church in Walnut Creek, California. There, Mary said, the ministers and the congregation were clear that homosexuals were sick, perverted, and condemned to eternal damnation. "And when they said that," Mary recalls, "I said, 'Amen.'"

For her part, Mary just knew that homosexuality was "an abomination to God." And even before she knew Bobby was gay, she conveyed her feeling to him in no uncertain terms. She remembers in sadness one incident that occurred when Bobby was fourteen. He had introduced her to a friend of his, a young girl. For some reason, Mary had loaned the girl a coat. Later, Mary learned that the girl had once had a lesbian encounter, and found herself unable to wear the coat again herself. "You can't love God and be gay," she told Bobby.

At about the same time, Bobby told his brother he was gay. Two years later, his brother told their parents. That night, the family was up until 4 A.M. talking and crying. They all agreed Bobby was a sinner, that he had to be cured by prayer and Christian counseling. Mary told him he had to repent or God would "damn him to hell and eternal punishment." She had faith that God would come to Bobby's rescue, but only if he read his Bible.

The Christian counselor recommended prayer and suggested that Bobby spend more time with his father. But Bobby's diary revealed that nothing was changing. "Why did you do this to me, God?" he wrote. "Am I going to hell? I need your seal of approval. If I had that, I would be happy. Life is so cruel and unfair."

His mother kept telling him he could change. "It seems like every time we talked, I would tell him that," she says. "I thought Bobby wasn't trying in his prayers." When Bobby became more withdrawn, she simply chalked it up to God's punishment. "Now," she says, I look back and realize he was just depressed."

When Bobby was twenty, in desperation the Griffiths decided he should move to Portland, Oregon, and live with a cousin. At first, the move seemed to help. He worked as a nurse's aide in a senior citizens' home and developed something of a social life. But the depression returned and deepened. A few months later, in his diary, he cursed God and added, "I'm completely worthless as far as I'm concerned. What do you say to that? I don't care." Again and again, he emphasized the shame and self-blame he felt over his sexual orientation. "I am evil and wicked. I am dirt," he wrote. "My voice is small and unheard, unnoticed, damned."

One Friday night in August 1983, Bobby had dinner with his cousin. She noticed that he seemed thoughtful, perhaps depressed. He seemed to want to talk about something, but said little. Then he left, saying he was taking a bus to go dancing downtown.

Early the next morning, two men driving to work noticed a young man, later identified as Bobby, on an overpass above a busy thoroughfare. As they described the next few moments, the boy walked to the railing, turned around, and did a sudden back flip into mid-air. He landed in the path of an eighteen-wheeler.

Bobby's body was return to Walnut Creek for funeral services in the Presbyterian church. The minister told the mourners that Bobby was gay, and suggested that his tragic end was the result of his sinning.

Later, the Griffiths met with their pastor for grief counseling. In her despair, Mary was seeking ways to atone for the loss of Bobby. She told the pastor she knew there were "other Bobbys out there" and asked how she could help them. The pastor merely shrugged his shoulders�and Mary never again returned to that church.

Mary Griffith's story perhaps reflects the ultimate human tragedy. She blames herself for the death of her son.

Mary says Bobby was "kind and gentle, with a fun-loving spirit." He was handsome, with clean-cut features and an Adonis-like body perfected by weight lifting. He loved old movies, particularly The Seven Year Itch with his favorite star, Marilyn Monroe. He loved Italian food and meeting people.

But the diary that he kept for the last two years of his life reveals a tortured soul. Tortured by passions he had been taught were sinful. Tortured by the bondage of what he called "society's rules." Tortured by fear of hell. "Gays are bad," he wrote, "and God sends bad people to Hell.... I guess I'm no good to anyone, not even God. Sometimes I feel like disappearing from the face of this earth."

The Griffiths attended Walnut Creek Presbyterian Church in Walnut Creek, California. There, Mary said, the ministers and the congregation were clear that homosexuals were sick, perverted, and condemned to eternal damnation. "And when they said that," Mary recalls, "I said, 'Amen.'"

For her part, Mary just knew that homosexuality was "an abomination to God." And even before she knew Bobby was gay, she conveyed her feeling to him in no uncertain terms. She remembers in sadness one incident that occurred when Bobby was fourteen. He had introduced her to a friend of his, a young girl. For some reason, Mary had loaned the girl a coat. Later, Mary learned that the girl had once had a lesbian encounter, and found herself unable to wear the coat again herself. "You can't love God and be gay," she told Bobby.

At about the same time, Bobby told his brother he was gay. Two years later, his brother told their parents. That night, the family was up until 4 A.M. talking and crying. They all agreed Bobby was a sinner, that he had to be cured by prayer and Christian counseling. Mary told him he had to repent or God would "damn him to hell and eternal punishment." She had faith that God would come to Bobby's rescue, but only if he read his Bible.

The Christian counselor recommended prayer and suggested that Bobby spend more time with his father. But Bobby's diary revealed that nothing was changing. "Why did you do this to me, God?" he wrote. "Am I going to hell? I need your seal of approval. If I had that, I would be happy. Life is so cruel and unfair."

His mother kept telling him he could change. "It seems like every time we talked, I would tell him that," she says. "I thought Bobby wasn't trying in his prayers." When Bobby became more withdrawn, she simply chalked it up to God's punishment. "Now," she says, I look back and realize he was just depressed."

When Bobby was twenty, in desperation the Griffiths decided he should move to Portland, Oregon, and live with a cousin. At first, the move seemed to help. He worked as a nurse's aide in a senior citizens' home and developed something of a social life. But the depression returned and deepened. A few months later, in his diary, he cursed God and added, "I'm completely worthless as far as I'm concerned. What do you say to that? I don't care." Again and again, he emphasized the shame and self-blame he felt over his sexual orientation. "I am evil and wicked. I am dirt," he wrote. "My voice is small and unheard, unnoticed, damned."

One Friday night in August 1983, Bobby had dinner with his cousin. She noticed that he seemed thoughtful, perhaps depressed. He seemed to want to talk about something, but said little. Then he left, saying he was taking a bus to go dancing downtown.

Early the next morning, two men driving to work noticed a young man, later identified as Bobby, on an overpass above a busy thoroughfare. As they described the next few moments, the boy walked to the railing, turned around, and did a sudden back flip into mid-air. He landed in the path of an eighteen-wheeler.

Bobby's body was return to Walnut Creek for funeral services in the Presbyterian church. The minister told the mourners that Bobby was gay, and suggested that his tragic end was the result of his sinning.

Later, the Griffiths met with their pastor for grief counseling. In her despair, Mary was seeking ways to atone for the loss of Bobby. She told the pastor she knew there were "other Bobbys out there" and asked how she could help them. The pastor merely shrugged his shoulders�and Mary never again returned to that church.