In

Gladys Mitchell’s latest book the scene throughout the story

is a Norman castle in the courtyard of which a small manor house

has been built.

In

Gladys Mitchell’s latest book the scene throughout the story

is a Norman castle in the courtyard of which a small manor house

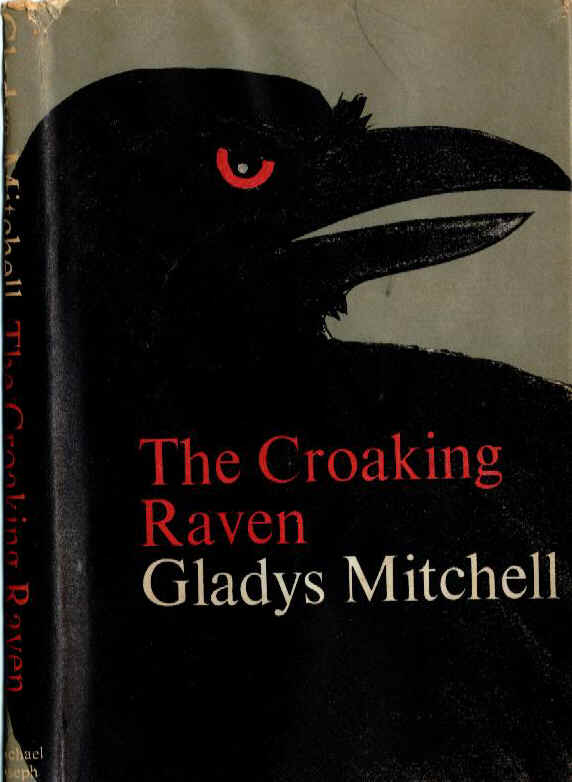

has been built.The Croaking Raven (1966)

1966 Michael Joseph blurb:

In

Gladys Mitchell’s latest book the scene throughout the story

is a Norman castle in the courtyard of which a small manor house

has been built.

In

Gladys Mitchell’s latest book the scene throughout the story

is a Norman castle in the courtyard of which a small manor house

has been built.

Under pressure from a small boy who wants to spend his summer holiday there, Dame Beatrice Lestrange Bradley is persuaded to rent the estate, only to find that an unexplained violent death occurred there some two years previously and that the murderer has never been found. The police have a suspicion that they know his identity, but there is no proof.

The dead man was Thomas Dysey, a previous owner of the estate, but it is so impoverished that there seems no reason for supposing that the murder was committed by one of his relatives for gain, although, in the absence of all other conceivable motives, there seems no other cause for his death.

It turns out that he has an illegitimate son named Henry and a legitimate son, Bonamy. The former is debarred by his illegitimacy from inheriting, and the latter who got into disgrace in England, is said to have died abroad. This leaves Thomas Dysey’s wife and his twin brothers, one of whom has adopted the illegitimate son, and these have become the main suspects.

During the early part of Dame Beatrice’s tenancy, the castle appears to be haunted by a singing ghost, but his spectral nature is soon in doubt, as, twice a week, on Wednesday nights and Sundays, he steals food from the manor house pantry. The situation is further complicated by the fact that on Wednesdays and Saturdays the house and castle are thrown open to the customary half-crown visitors, one of whom may be the murderer.

The singing ghost appears to be exorcised when one of the dead man’s twin brothers is also murdered, and in precisely the same way. This presupposes that the murders are dynastic and that possession of the almost worthless property is the murderer’s ultimate aim. This is the police theory.

There is also a strong local rumour that the manor house once sheltered Jesuit priests during the time when the Catholic faith was proscribed, and that these left behind a treasure known as the Dysey Hoard. Nobody seems to know whether the treasure is still in existence or, if so, what form it takes, and Dame Beatrice tries to trace its history in the hope that this will shed some light on the two murders.

Two other possible suspects exist in the form of a woman whom one of the brothers has married, and her sister, who is Henry’s mother, but although these women could have murdered Thomas as an act of revenge for begetting Henry, there seems no reason why they should have killed the second brother. All appears to turn upon whether the legitimate son, Bonamy, is alive or dead. When he turns up, not only alive but married with a son of his own, the mystery of the two murders seems insoluble until Dame Beatrice tracks down the truth.

My review:

With her thirty-ninth novel, published in 1966, Gladys Mitchell indulges her love of historically romantic settings—here, a Norman castle—and her love of complications, with the cluttered tale of the owners of the castle, in one of the most complicated stories she has written since Death and the Maiden (1947)—and, as one character points out, everything “sounds like something out of a nineteenth century horror chronicle”—the genre Mitchell was parodying here.

A castle is always an attractive place to set the book, ranking alongside the haunted house—and if the castle is haunted, the author admirably attracts the reader’s attention twice over. Here, Dysey Castle, owned by a former patient of Dame Beatrice Bradley’s, seems to be haunted by a ghost—or, as Dame Beatrice Bradley, staying in the castle with the family of her secretary Laura, suspects, “an uninvited guest”: a mysterious intruder. Although the castle motto “indicates neither militant nor mercenary sentiments”, it is soon revealed that the heraldic ravens are linked with a tale of family murder and betrayal in the distant past—with obvious similarities to a certain masterly short story of John Dickson Carr’s, “Terror’s Dark Tower”. Ravens also crop up in “the Raven’s Hoard”, a buried treasure, and, as Laura points out, “stories of treasure are always interesting”. With the discovery that there has been a murder in the more recent past—in fact, only two years before the story takes place—the castle lives up to its name: “Dysey by name and dicey by nature, that castle”.

The family business also has its attractions, although it is difficult to tell many of the characters apart, the reader wholeheartedly agreeing with the statement that “they’re damned mysterious and they’ve got too many relatives”. However, things begin to clarify by a third of the way through. There are secret marriages, illegitimate babies, changelings, survivorship of heirs, the dead being not dead but shamming, as well as the possibility of murder for inheritance. “Ah, there's deep callin’ to deep, and still waters a-runnin’ likewise, in these old fam’lies, Mrs. Gavin, mam, you mark my words”, comments a rustic. And indeed the local belief that the Dyseys are “a funny lot, and this is a family matter” is soon borne out by the discovery of a second corpse.

Although too many of the characters are suspected of being mad, and it is difficult to tell many of them apart, especially when they begin masquerading as each other, the characterisation is above average, although certainly not up to the high standards she set in the 1930s and 1940s, where every character had a distinctive voice and personality. Let the reader try to forget Mrs. Bradley, Mrs. Puddequet, Mrs. Coutts, Hanley Middleton, Sir Rudri Hopkinson, or Edris Tidson if he can. Laura Gavin’s son Hamish is amazingly mature for a ten-year old. However, does anyone age in a Mrs. Bradley novel? Sally Lestrange doesn’t age a day between her appearances in Laurels are Poison (1942) and Winking at the Brim (1974). Denis Bradley ages more than ten years in the six years between Laurels are Poison and The Dancing Druids (1948), while not ageing a day in the six years between Dead Men’s Morris (1936) and Laurels are Poison. Laura herself ages perhaps only five or six years in the forty-two years between Laurels and her last appearance, The Crozier Pharaohs (1984), and is engaged for eight years. Perhaps the key to this timelessness is in Laura’s statement that people are “as old as [they] feel, same like me, and I usually feel a fairly skittish twenty-two or so.” “No wonder Hamish seems older than his years.”

With Dame Beatrice hiding behind Laura Menzies for most of the late 1950s and 1960s, it is a pleasure to say that Mrs. Croc, who takes “a beautifully detached view of life in general, and of the eccentricities of most of her acquaintances in particular”, is firmly in control here, Laura properly relegated to the rôle of Watson. The case certainly needs Dame Beatrice at the helm, for “none of it makes sense”, or, to look at it another way, “it all makes sense. The thing is that it don’t add up right.” The nonsensical nature of the case is largely due to Dame Beatrice’s alarming and infuriating habit, “as happens far too often, [of] speak[ing] in riddles”.

The solution, when it does come, is by no means well unfolded, and it is difficult to say with certainty who the murderer is, and why they committed the crimes, even though their names and motives are given. Despite this, “there's a romantic Childe Roland flavour about this expedition which appeals to my childish nature.”