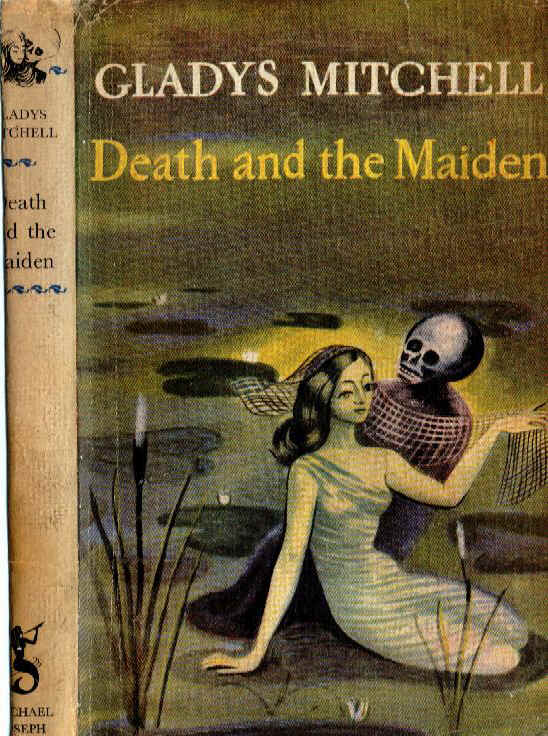

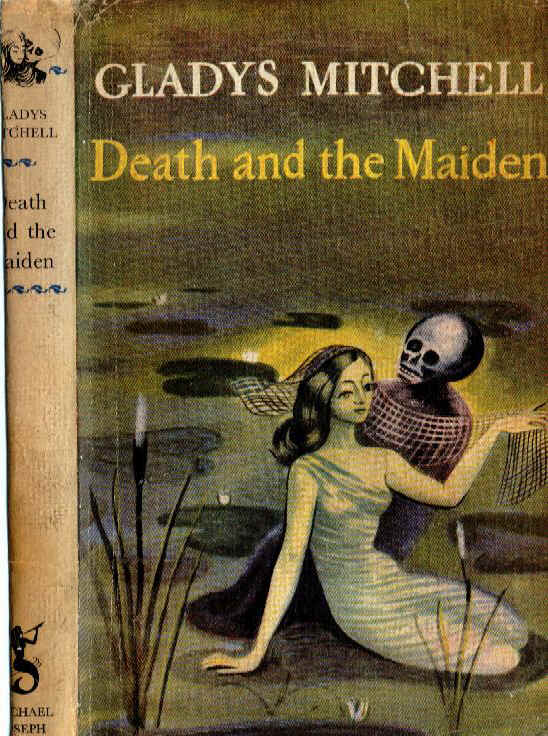

Death and the

Maiden (1947)

1947 Michael Joseph blurb:

The

great detectives of fiction are men of varied and brilliant

gifts—Chief Inspector Alleyn, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule

Poirot, Albert Campion and their peers—but in this

glittering company Gladys Mitchell’s famous Mrs. Bradley,

‘the greatest of women detectives’ as she has been

called, is well able to hold her own. ‘Mrs. Bradley is a

lovely ancient dame,’ wrote John O’London’s

Weekly, reviewing one of her recent cases, ‘bouncing

happily through crime with a will and a wit as deadly as a

snake’s tongue.’

The

great detectives of fiction are men of varied and brilliant

gifts—Chief Inspector Alleyn, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule

Poirot, Albert Campion and their peers—but in this

glittering company Gladys Mitchell’s famous Mrs. Bradley,

‘the greatest of women detectives’ as she has been

called, is well able to hold her own. ‘Mrs. Bradley is a

lovely ancient dame,’ wrote John O’London’s

Weekly, reviewing one of her recent cases, ‘bouncing

happily through crime with a will and a wit as deadly as a

snake’s tongue.’

In Miss Mitchell’s new story, Mrs. Bradley is at the top

of her form—as she certainly needed to be in the astonishing

tangle of crime which confronted her when an urgent summons from

an old friend took her to the Domus Hotel at Winchester. It all

began with a report of a water nymph alleged to have been seen in

the waters of the Itchen—a fantastic tale, but no more

fantastic than the murder of two boys and the whole fantastic

chain of crime which sprang from it, and far from enough to

defeat the unerring acumen of Mrs. Lestrange Bradley.

My review:

‘This

seems the place for naiads. It certainly isn't the spot for

two murders, is it? I do think Cathedral cities, and these

water-meadows, ought to be immune from horrors, and policemen,

and nasty little brutes like Tidson.’

‘…These

murders are not native to the place. They have been planted

here by the devil, or some of his agents.’

The blurb of Death

and the Maiden (1947) calls the plot an “astonishing

tangle of crime”—a description justified by the

events of one of Gladys Mitchell’s half-dozen masterpieces,

a tale at once witty, imaginative, original, and full of

incident. Yet this complexity—a veritable symphony of

complexity—seems neither cluttered nor convoluted, such is

the considerable skill with which the author unwinds her yarn.

The setting is the

cathedral city of Winchester, where a naiad has been seen in the

River Itchen (and is later heard to quote The Frogs of

Aristophanes—sheer Mitchellian genius), “which

ordinarily offered a habitat to nothing more sinister than

a pike, more beautiful than the grayling or more intelligent than

the brown trout”, a locale which Mitchell evokes with

her customary lyrical grace—and, “in a city which

harbours a naiad in a chalk stream, anything may happen”.

Edris Tidson, a retired banana-grower recently arrived from the

Canaries with his beautiful half-Greek wife Crete, and staying

with his cousin Priscilla Carmody and her niece Connie (much to

their discomfort, for Tidson is by way of being a parasite), is

much attracted by the idea of the naiad, and moves to the Domus

Hotel, Miss Carmody paying the bills for the four of them.

The characterisation of the four suspects is particularly sharp,

although, as Mrs. Bradley reflects, “the Carmody

household, comprising, as it did, the fantastic Mr. Tidson, the

astoundingly beautiful Crete, the discontented Connie and her

troubled, respectable aunt, appeared to have something more in

common with the surreal than with the real”.

Mrs. Bradley is

asked by Miss Carmody to vet Tidson, whom she believes to be mad,

and whom the natives of the Canaries feared as having the evil

eye—and finds herself in particularly strange territory,

even by Mitchell’s standards. Although Tidson is

clinically sane (if undeniably eccentric), Mrs. Bradley is

suspicious of Tidson’s interest in the naiad, feeling that “a

middle-aged gentleman of slightly eccentric mentality could cause

a naiad to cover a progressive multiplicity of actions, including

quite a number of sins. It was a fascinating field of

surmise, in fact, to work out what sins in particular the naiad

could help to screen”. Connie Carmody is disturbed

during the night by the squeaking ghost of a nun, which Mrs.

Bradley feels may have been created for human reasons (the hotel

porter, Thomas, a masterpiece of comic invention, argues that “hotels

are not made to be haunted. The guests, maybe, couldna

thole it. Ghaisties wadna come whaur they werena

welcome”), and which she believes may have entered

Connie’s room through that Mitchell trademark, the secret

passage.

A small boy is

found dead by the river, perhaps drowned by the naiad, perhaps

(as the police believe) murdered by one Potter, who found the

body, and with whose foster mother he was believed to be having

an affair. Miss Carmody differs, however, and, believing

Tidson to be guilty of the crime, asks Mrs. Bradley to begin her

enquiries, which she does in an absolutely superb way,

disquieting suspects left right and centre, and giving vent to

her customary eldritch cackle: “not a mirthful sound, and

Laura, who had learnt to regard it as a war-cry, looked at her

rather in the manner of stout Cortez regarding the Pacific”.

Laura Menzies (who meets and becomes engaged to Det. Insp. Gavin,

disguised for most of the story as an angler) and her two

friends, Alice Boorman (who discovers a second dead boy) and

Kitty Trevelyan, ably assist her, and, for once, the Three

Musketeers are an integral part of the story and not dragged in

for reasons of sentimentality. As her investigations

proceed, Mrs. Bradley finds herself “more and more

interested in the strange little man [Tidson]. His

potentialities, she felt, were infinite. She longed to ask

him, point-blank, whether or not he were a murderer, but she felt

that this would ruin their friendly relationship and defeat the

object of the question, which was, quite simply and

unequivocally, to find out the answer.” Her

suspicions are justified—Tidson’s guilt is suspected

early on, and stated halfway through; this is one of those

stories where the detective interest lies in piecing together

motive (Mitchell juggling several possibilities, including

practice makes perfect, gain, and revenge in the air) and method,

and in finding proof—of which there is plenty of

psychological proof, but “no material proof

whatsoever”, despite a plethora of sandals, black eyes

(a brilliant touch, this), rafts, wills, illegitimacy, secret

passages, and finger-prints. The problem is further

complicated by the suspicious behaviour of other characters,

especially Connie Carmody.

The ultimate solution to the mystery is particularly

ingenious: a devilishly subtle motive relying on bluff,

double-bluff and triple-bluff. Although all the clues to

the mystery are provided, it will be an intelligent reader who

finds the true solution before Mrs. Bradley chooses to reveal

it. Although every act is attributable by the end, and the

solution quite logical, there are a few points improperly

explained: why was the evidence planted when the individual in

question knew Mrs. Bradley had already searched the hole?

How did the Tidsons hope to make people infer that the dog had

been killed by a sadistic lunatic by throwing a boot into the

river? Why (and Jason Hall has already pointed this out in

his excellent review)

was Crete Tidson naked when drowned, why were her clothes hidden

in the river, and why was she placed in the river? There

are a few minor signs of carelessness: the boy’s age in the

paper on pp. 40 and 43; Connie’s whereabouts on pp. 75 and

76; and the victim’s name changing from Hugh to John Biggin.

To

the Bibliography

To

the Mitchell Page

To the

Grandest Game in the World

E-mail

The

great detectives of fiction are men of varied and brilliant

gifts—Chief Inspector Alleyn, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule

Poirot, Albert Campion and their peers—but in this

glittering company Gladys Mitchell’s famous Mrs. Bradley,

‘the greatest of women detectives’ as she has been

called, is well able to hold her own. ‘Mrs. Bradley is a

lovely ancient dame,’ wrote John O’London’s

Weekly, reviewing one of her recent cases, ‘bouncing

happily through crime with a will and a wit as deadly as a

snake’s tongue.’

The

great detectives of fiction are men of varied and brilliant

gifts—Chief Inspector Alleyn, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule

Poirot, Albert Campion and their peers—but in this

glittering company Gladys Mitchell’s famous Mrs. Bradley,

‘the greatest of women detectives’ as she has been

called, is well able to hold her own. ‘Mrs. Bradley is a

lovely ancient dame,’ wrote John O’London’s

Weekly, reviewing one of her recent cases, ‘bouncing

happily through crime with a will and a wit as deadly as a

snake’s tongue.’